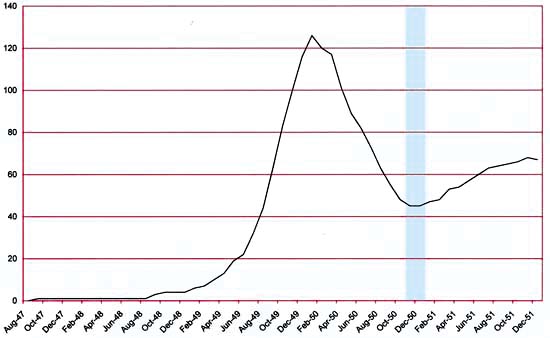

(May 1951 – July 1951: Young Romance #33 – #35, Young Love #21 – #23)

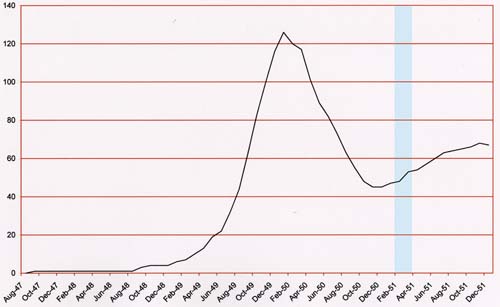

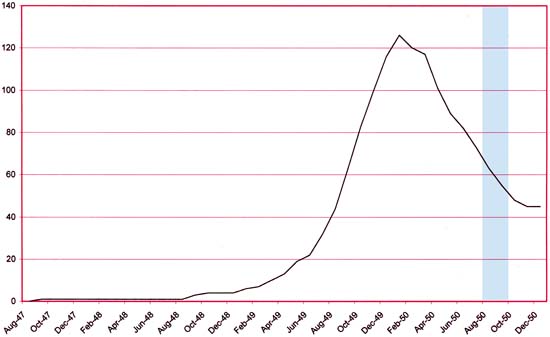

Number of Romance Titles 1947 – 1952 (the period covered in this chapter is shaded in blue)

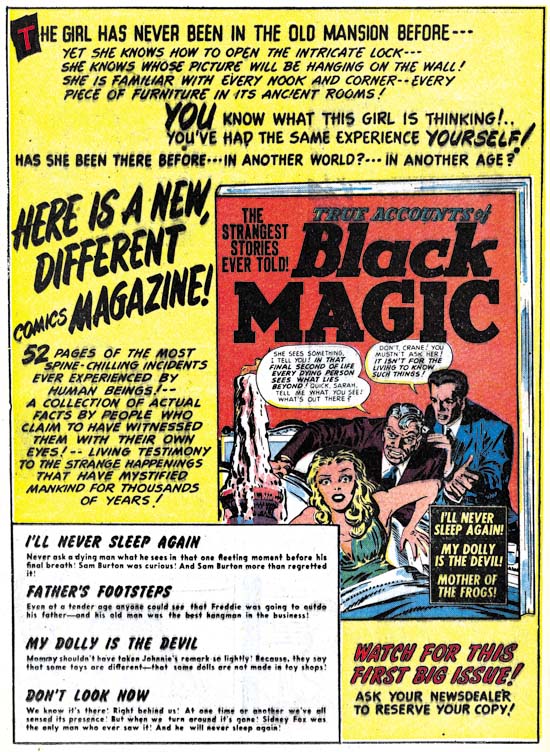

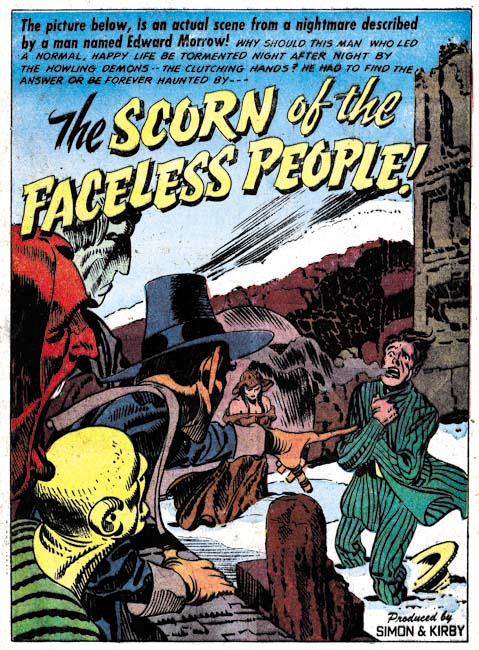

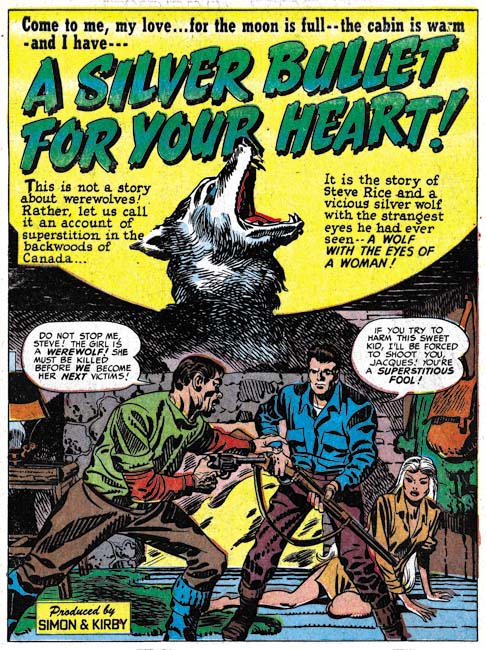

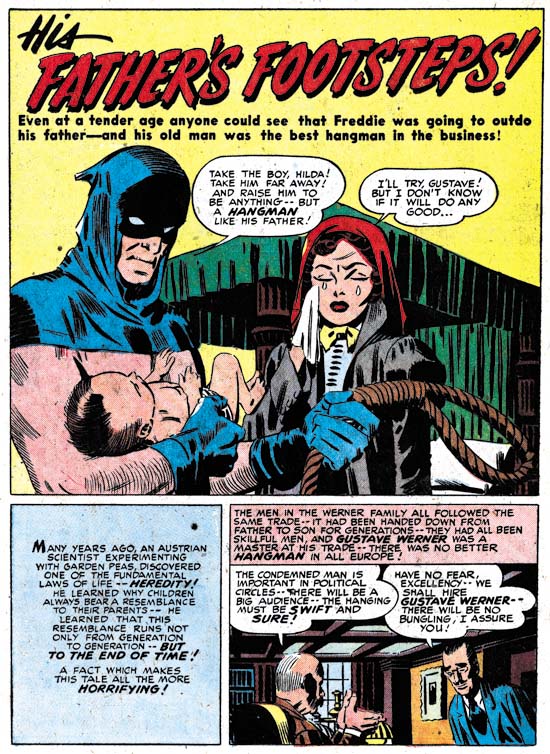

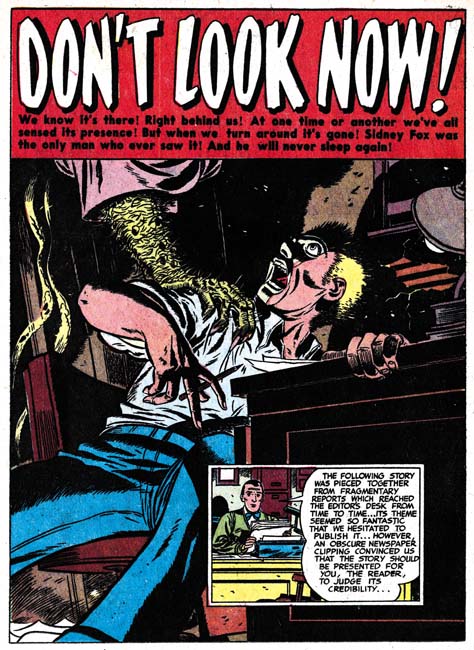

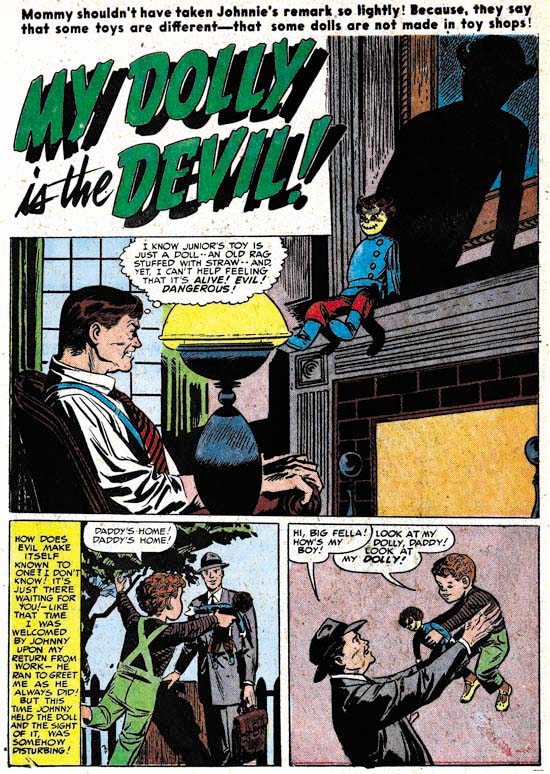

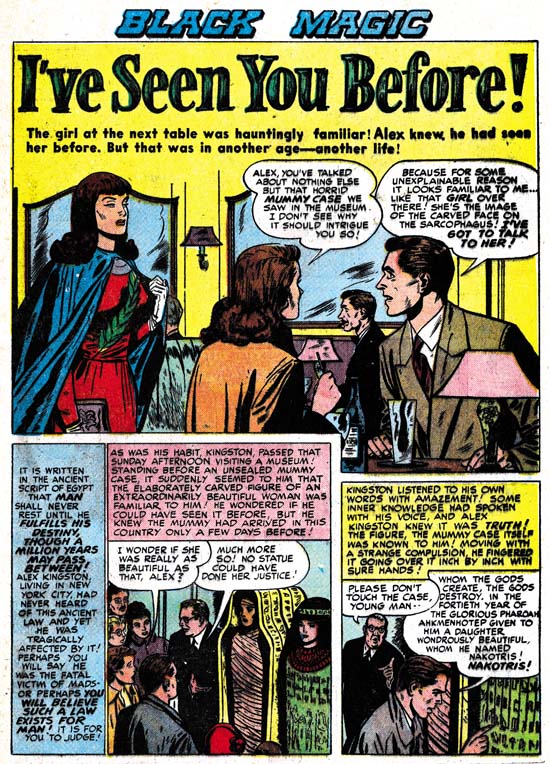

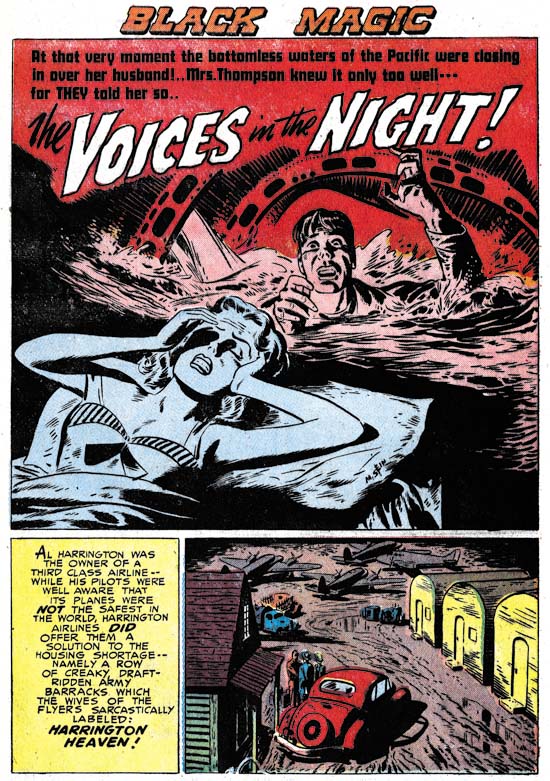

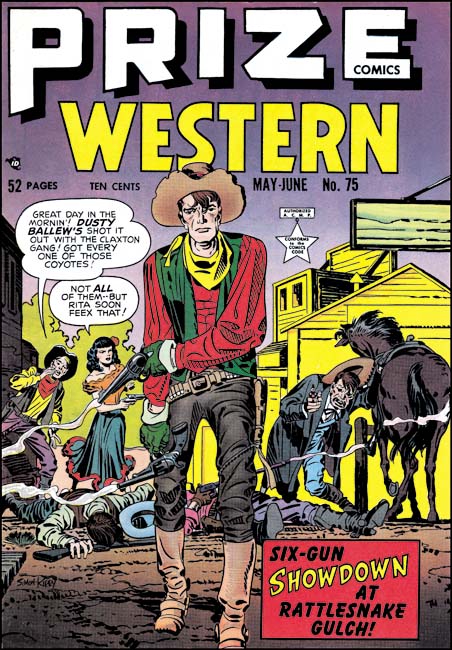

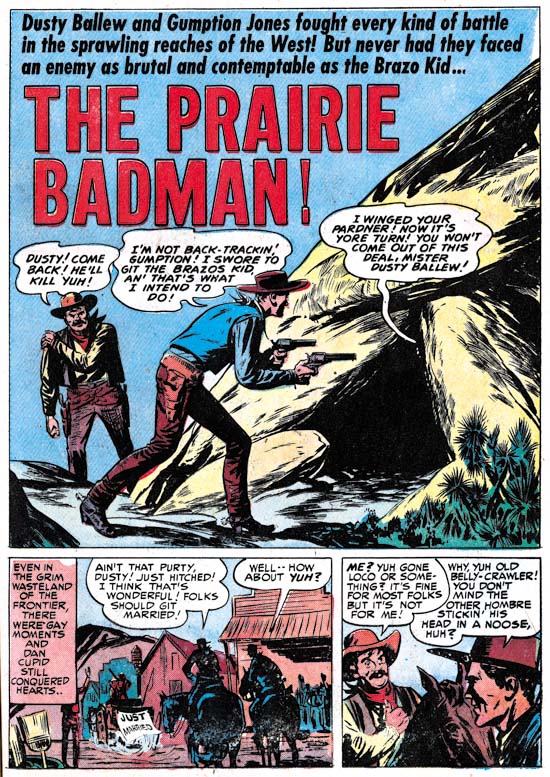

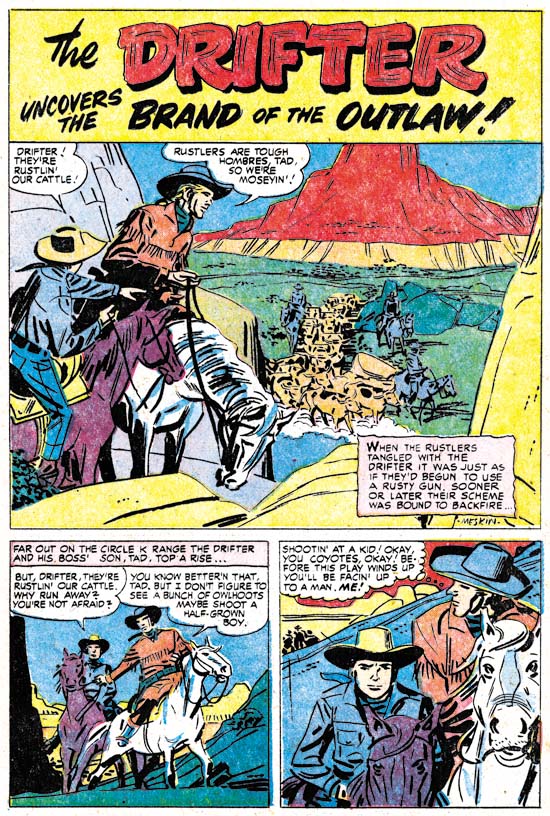

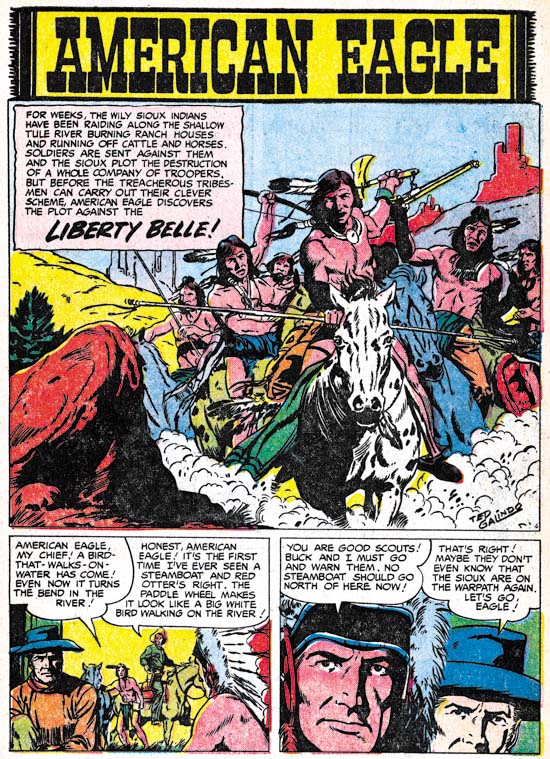

Besides the two romance titles, Simon and Kirby were also producing bimonthly Black Magic (for Prize) and Boys’ Ranch (for Harvey). At this point I believe it can safely be said that Joe and Jack had little to do with the Prize crime titles. While Mort Meskin and Marvin Stein would appear in Prize comics both produced by Simon and Kirby and those that were not, they were the only artists that seemed to do so. John Severin had been another artist that worked in both the romance and crime titles but at this point the only Prize title he was working on was Prize Comics Western (also not a Simon and Kirby production).

Young Romance switched back to drawn covers for May and June (Young Love had already been using art covers). Both titles would revert to photographic covers for their July issues and would remain using photo covers until 1954. I really do not know what to make of YL consistently and YR sporadically using art covers for a period of about a year.

In a certain respect Jack Kirby was the primary studio artist during this period as in fact he was during the entire time Joe and Jack produced comics together. Except for a period in 1954 and My Date #4, Jack would provide the art for the cover of all Simon and Kirby productions that did not use a photograph. During this period Kirby would also do the lead story for all the issues of Young Romance and one for Young Love (YL #21). But if the total number of pages of art produced is used to judge who was the primary artist then Mort Meskin wins out be a large margin. For these six romance issue Jack did a total of 51 pages of art while Mort did 80. The difference is all the more striking with the knowledge that Meskin did all his own inking while Kirby did not. I will say that I feel that Meskin’s art sometimes suffers from his higher rate at producing art while Kirby always seems to provide high quality work no matter how many pages he drew. It also pays to compare Jack’s 51 pages with Bill Draut’s 36 and John Prentice’s 34 or 37 pages (the uncertainty about Prentice page count is due to the short feature “Will You Help Me?” from YL #21 which I will discuss below). Jack was still working at a high rate; it is just that Mort was even more exceptional. Marvin Stein is another contributor during this period with only 3 stories and 23 pages. There are 3 very short pieces (a total of 7 pages) that I have not been able provide artistic credits for.

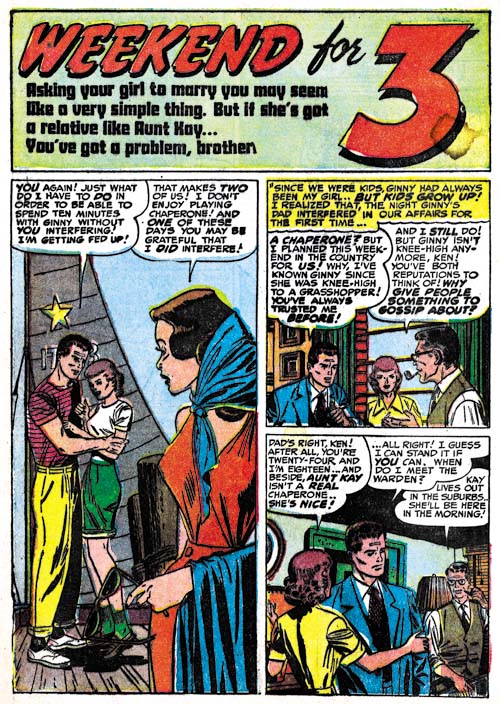

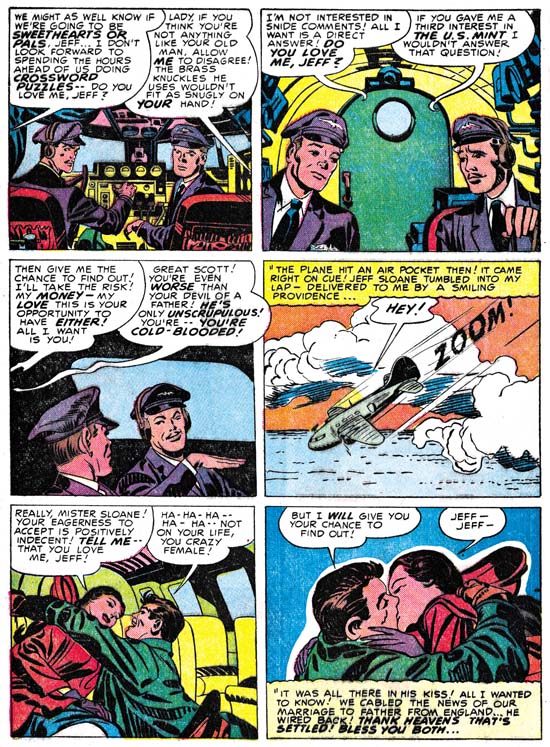

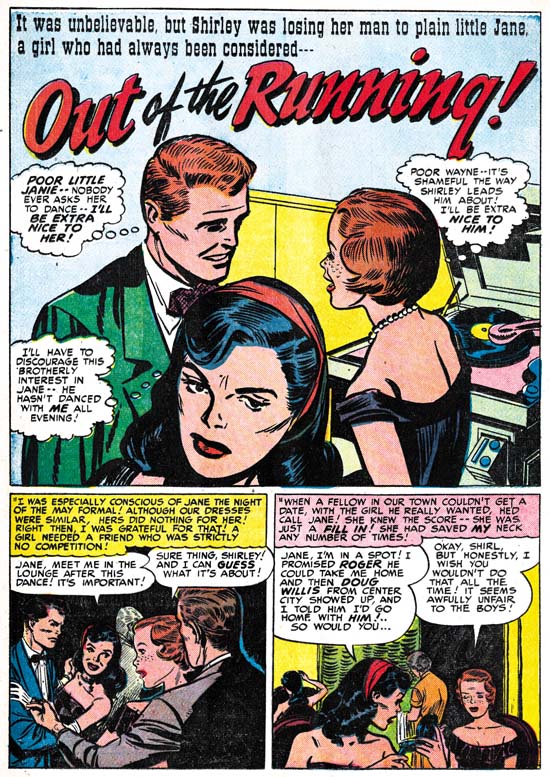

Young Romance #34 (June 1951) “Old Fashioned Girl”, art by Jack Kirby

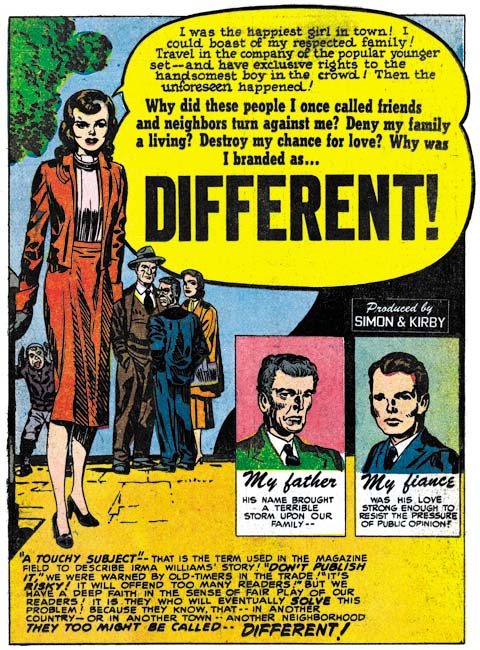

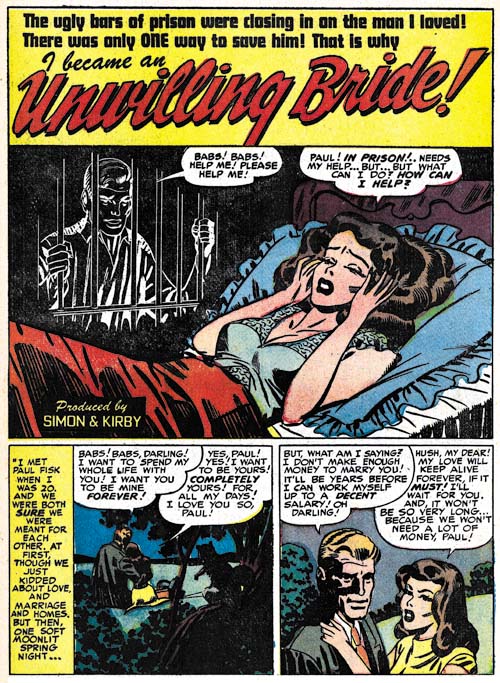

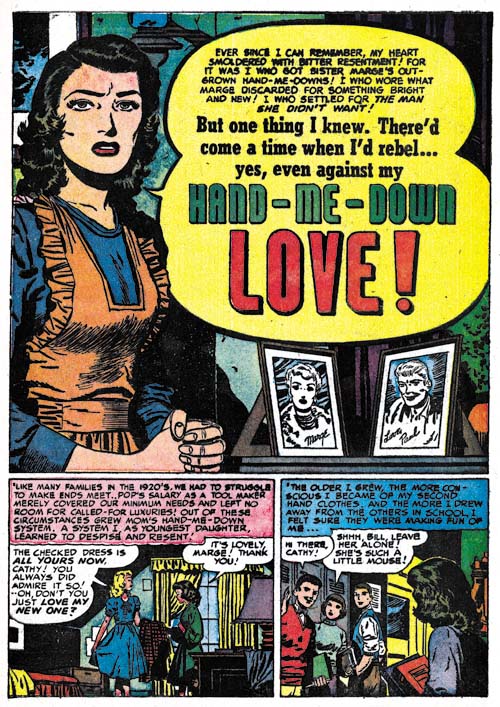

Perhaps others do not share my view, but I find Kirby’s confessional splashes powerful drawings despite their lack of action. While Kirby is generally (and quite reasonably) famous for his dynamic drawing it was a mark of his genius that he could be so effectively in such static compositions. Much of this has to do with Jack’s careful use of characterization. I have said it before but it is worth repeating, I do not agree with those who claim that Kirby did not draw beautiful women. It is true the protagonist in the splash for “Old Fashioned Girl” does not have the type of attractiveness that would be found in a beauty pageant contestant. But her frail like form has its own beauty and most importantly is totally appropriate for her antique dress style. The thing is Kirby did not draw the same women over and over but created unique individuals that were well matched to the theme of the story. The woman’s downcast eyes and the demur way she holds her hands augment the characterization. The old woman looking on and all the antique surroundings complete the picture. If all that was not enough, Jack has added a small panel that is not a story panel but another means of showing the conflict between the lady’s old fashioned ways and what was then modern society.

I feel that Jack Kirby’s romance splashes are much more interesting then the covers. I present the line art for the cover of YR #34 which is based on the “Old Fashioned Girl” story in a post above (My Two Cents). The reader can compare the two and reach their own conclusion.

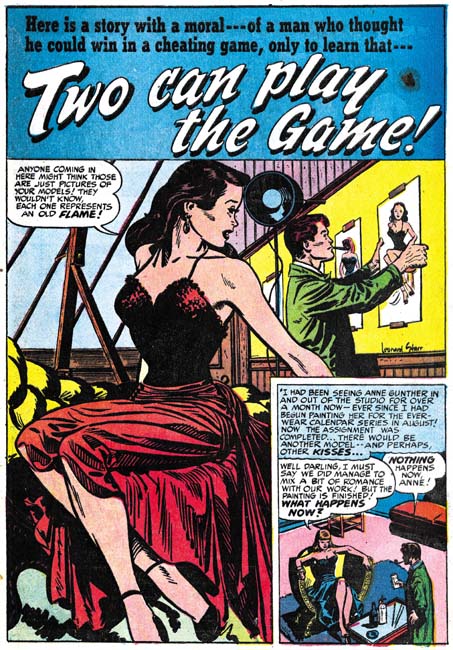

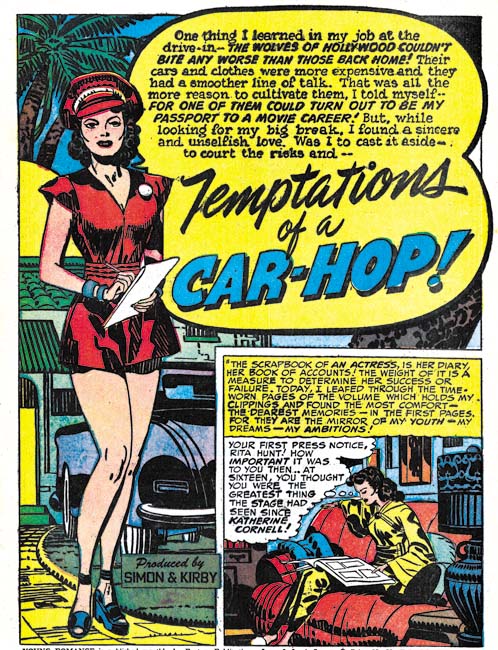

Young Romance #35 (July 1951) “Temptations of a Car Hop”, art by Jack Kirby

The splash for “Temptations of a Car Hop” provides a nice contrast to the one in “Old Fashioned Girl”. The protagonist was certainly meant to represent a thoroughly modern woman, or at least what would have been modern in 1951. However 58 years later and the car-hop has disappeared a casualty of the fast food drive through. I do remember them from my younger days but none that I ever visited had such and attractive waitress wearing such a short dress.

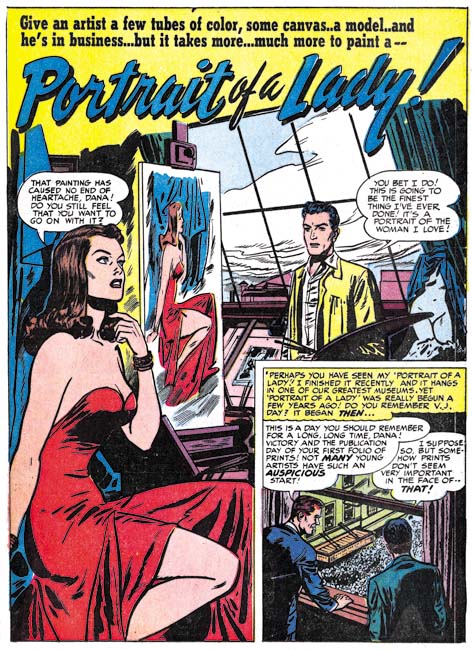

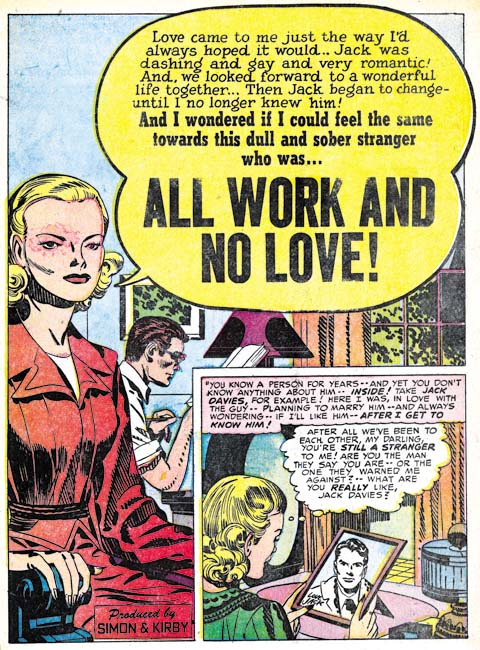

Young Love #21 (May 1951) “All Work and No Love”, pencils by Jack Kirby inks by Marvin Stein

With all the work I am doing for Titan’s Simon and Kirby library, I have not had time to devote to investigating the various inkers of Jack Kirby’s work. Still from time to time I come across a piece that just screams a particular inker. Such is the case with “All Work and No Love”. In the splash the simplicity of the woman’s eyes and eyebrows and the slight angle they have in relation to one another leaves little doubt that Marvin Stein was involved in the inking. The same sort of eyes appears elsewhere in the story as well. Also there are some cases where the eyebrow is extended into a crease of the forehead which is a trait often found in Stein’s own art. I should point out that inking of Kirby pencils in the Simon and Kirby studio was like an assembly line with various artists taking care of different chores. So when I say Marvin Stein inked this story I am saying no more then he was the one inker of this work that I have been able to identify but there are others that I have not. In this case Marvin seems to have done the outline inking, the first step in the inking process. Note however how the spotting uses the picket fence crosshatching, drop strings and shoulder blots that are characteristics of the Studio Style inking (see my Inking Glossary for explanations of the inking terminology that I use). Stein’s inking of his own work does not use such techniques. Further Stein’s own inking was a bit rough and lacked control. It would improve greatly in future years but at this point I cannot believe he could have been the artist that did the spotting.

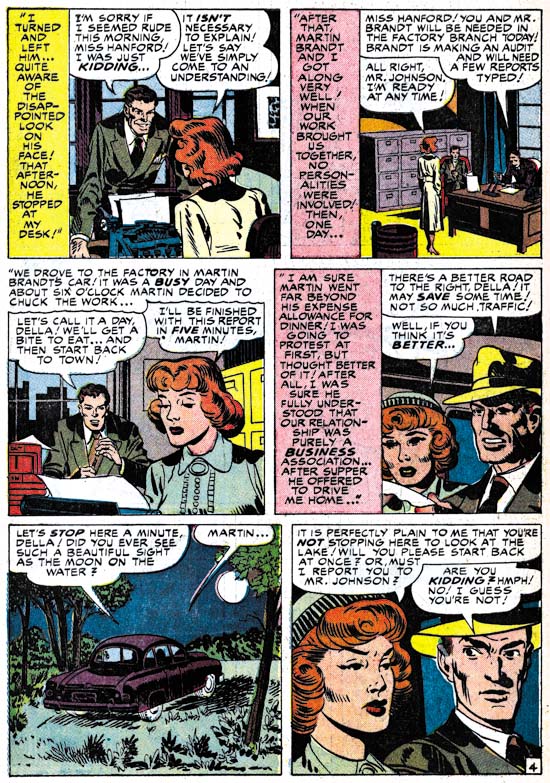

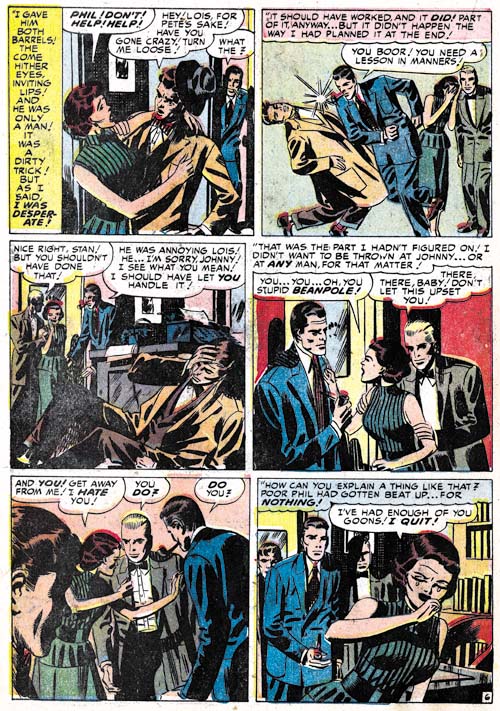

Young Romance #33 (May 1951) “Take a Letter, Darling” page 6, art by Mort Meskin

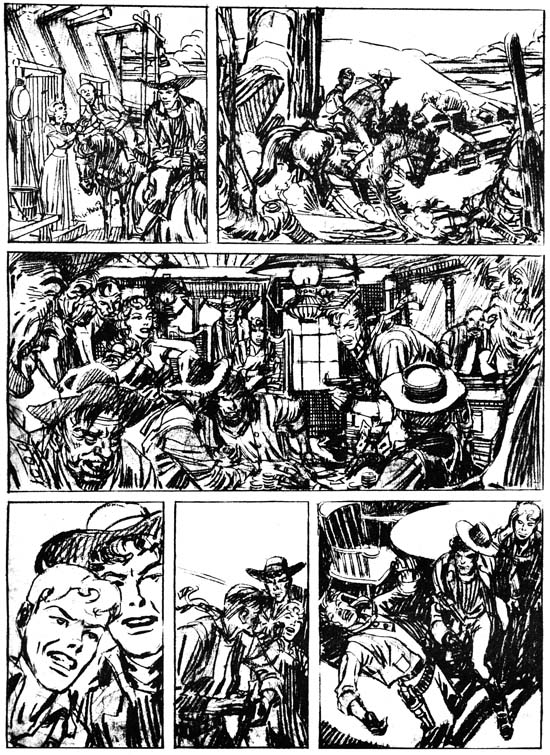

While I have frequently remarked how action is more often found in the romance stories Jack Kirby draws I do not want to leave the impression that action played no part in stories drawn by other studio artists. So I thought I would provide some examples. First up is a page by Mort Meskin. Meskin has his own unique and very stylized version of a slugging as can be seen in the second panel. Note in particular how the angular position of the victim’s head and how his legs are folded up beneath him. I say it is stylized both because Mort uses it over and over again and because it appears nothing like how a photograph a fight would look. I am not using the term stylized in a negative manner because I believe a comic artist job is to tell a story, not to try to produce a sequence of photorealistic images. With his technique Meskin has condensed several instants of time into one image (the victims head responding to being struck by the fist is the first instant, with the torso soon following and finally the loss of control of the legs as the effect of the knock out is completed).

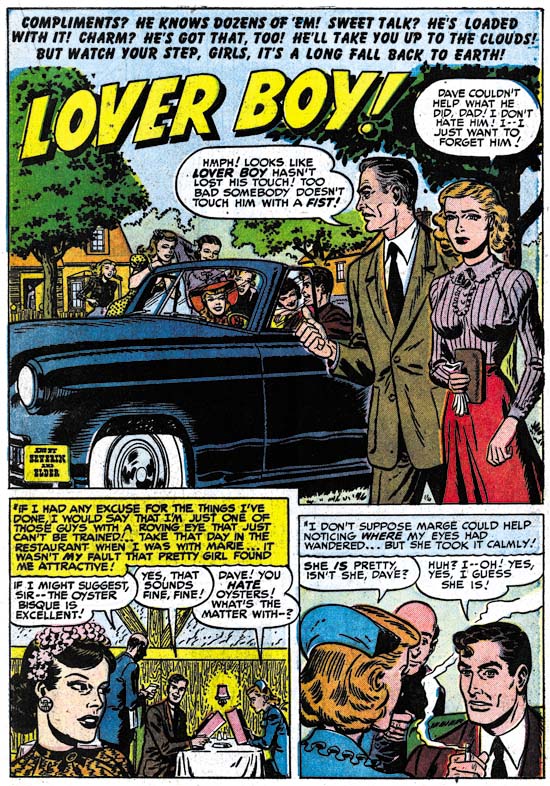

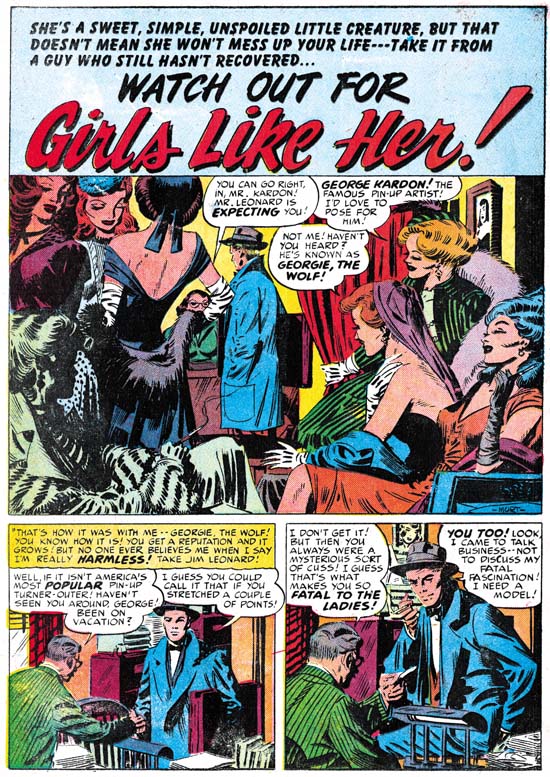

Young Romance #33 (May 1951) “Not in the Act” page 8, art by Bill Draut

The second example of a fight comes from Bill Draut’s “Not in the Act”. Draut uses an interesting compositional device of presenting the fighters in depth. I am not sure where Bill got this idea but it is pretty effective. I do not believe I have seen Draut use it before so it is not as an important part of his repertoire as Meskin’s or Kirby’s more stylized slugging.

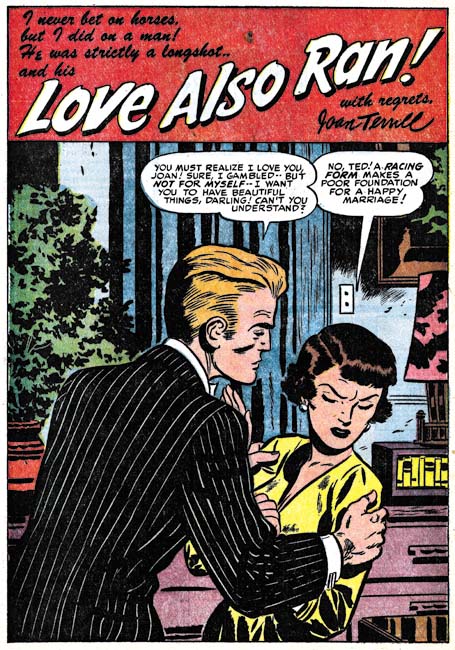

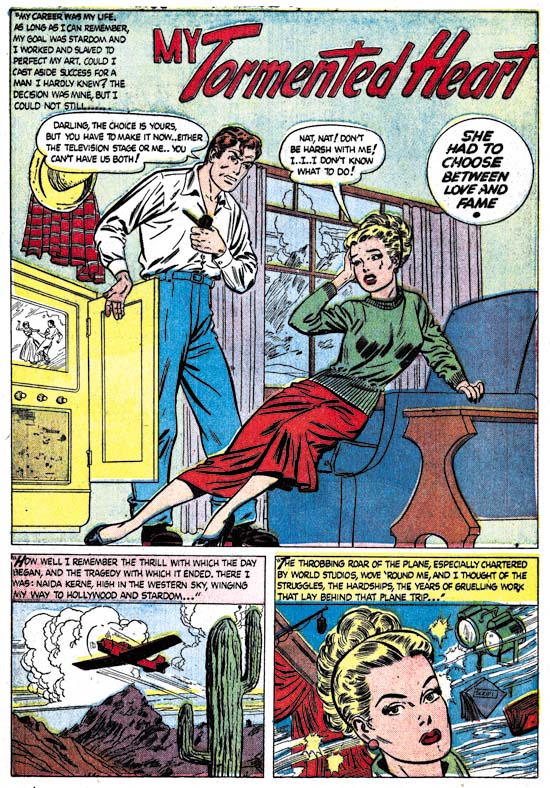

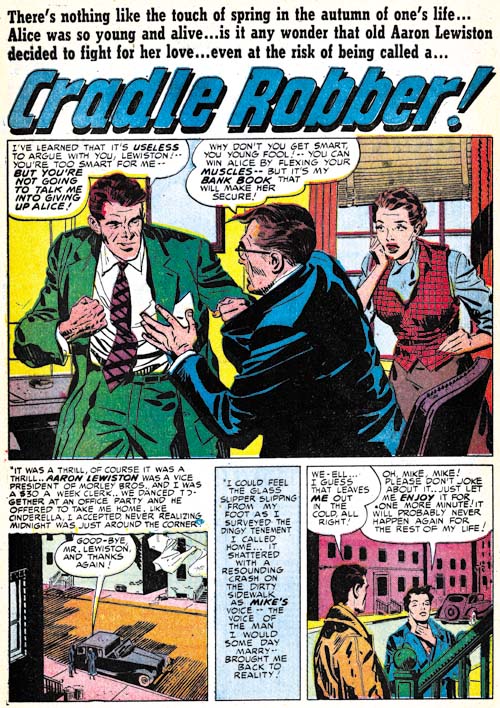

Young Love #23 (July 1951) “Cradle Robber”, art by John Prentice

The splash for “Cradle Robber” provides an example of a fight as portrayed by the more recently arrived studio artist. Actually calling it a fight is not quite correct as Prentice has chosen to present the moment just before the punch is thrown. The other thing about this splash is that it is actually a teaser as there would be no fight seen in the story. It is however the closest example of a fight that I could find by John Prentice in the period covered by this chapter.

Young Romance #35 (July 1951) “The Catskill Man-Chasers” page 8, art by Mort Meskin

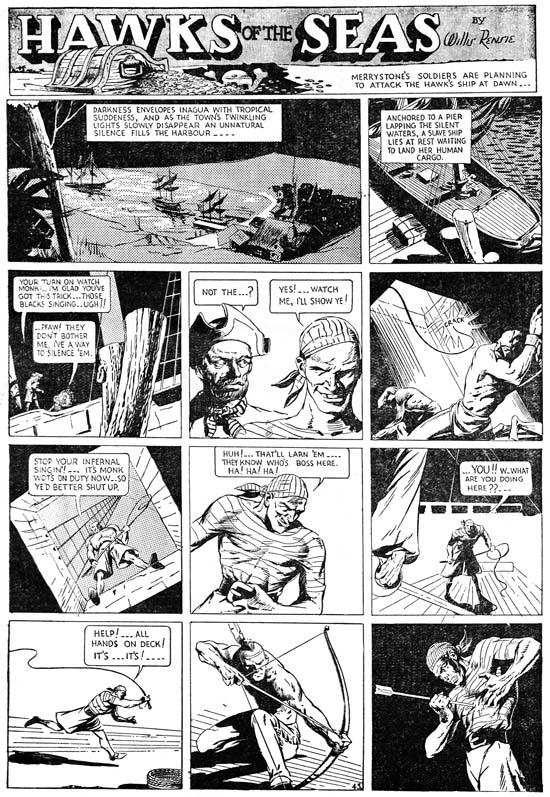

Mort Meskin is famous for his use of blacks but that does not always show up in his romance art. That may in part be a result of his high rate of art production. But it may also be because for Meskin telling the story properly had become a higher priority then making interesting art. Sometimes Meskin would have the best of both worlds (story and art) as in this page from “The Catskill Man-Chasers”. For many comic artists only night scenes would get an abundance of black but here Mort uses it to make the light parts so much brighter as would be appropriate for a hot summer day by the pool. Mort also uses it in the second panel to hide in plain sight Tom, the love interest of the story. Tom’s presence in the panel is not obvious at a glance because Mort only provides a silhouette but at closer examination the pipe clearly indicates that the shadowed figure is Tom. Starting with the second panel, Meskin moves in closer and closer so that the view progresses from a crowded scene to one that focuses on just the couple. While Meskin is restricting the focus he is paradoxically increasing the use of black until in the final panel the reader can make out only a little of the faces. While Mort has obscured the features he has made the scene all the more intimate. It is a masterly orchestrated page all the more so because nobody else working for Simon and Kirby, including Kirby, worked blacks anything like this.

Young Romance #33 (May 1951) “Charity Case” page 5, art by John Prentice

Since John Prentice is a new addition to the Simon and Kirby studio it behooves me to begin to try to discredit the opinion that too many Kirby fans have that Jack supplied layouts for the various studio artists. While that is true for some of the more minor artists that Simon and Kirby occasionally used it is decidedly not true for the more common talented artists. John Prentice certainly falls in the talented group and except for a special case from years later and from outside the romance genre Prentice did not work from Kirby layouts. One piece of evidence in Prentice’s case comes from the dramatic close-ups like panel 3 in the page shown above. While Jack Kirby occasionally did close-ups they generally are not as radically cropped as Prentice often uses.

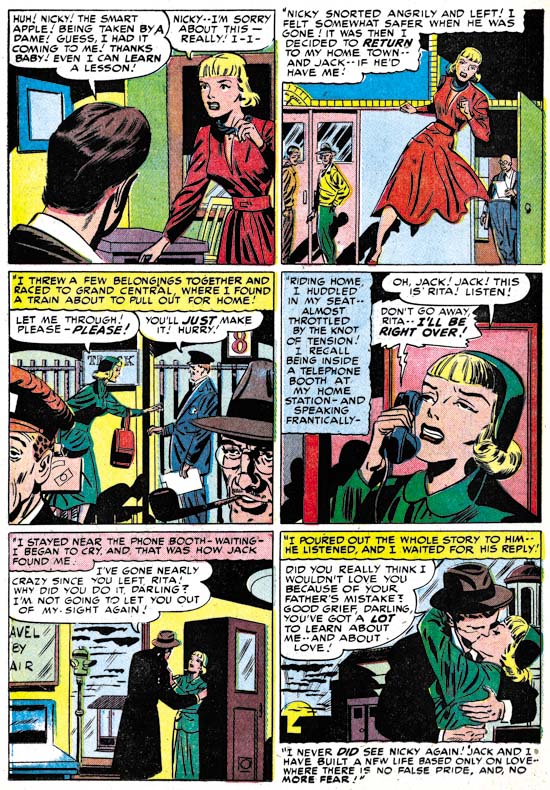

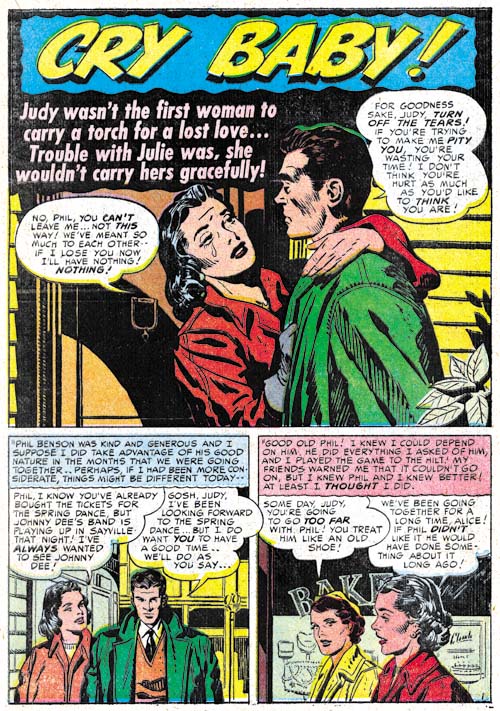

Young Love #22 (June 1951) “Cry Baby”, art by John Prentice

It was not uncommon for Studio Style inking techniques to show up in splashes of stories of the artists that otherwise were inked with other brush mannerisms. Often I suspect it was the work of Joe or Jack stepping in to touch up the art. That is not however what I judge happened to “Cry Baby”. All the major features of the studio style are present in this page if not in the splash itself; picket fence crosshatching, drop strings, abstract shadow arch and shoulder blots (see my Inking Glossary). What makes me believe this was not the work of Simon or Kirby is the way the picket fence crosshatching is done particularly on the man’s jacket. The rails are not done in the standard way of the Studio Style but match Prentice’s cloth folds. The pickets vary in both spacing and execution in ways not typical of Simon and Kirby. This leads me to believe that the spotting was actually done by Prentice himself.

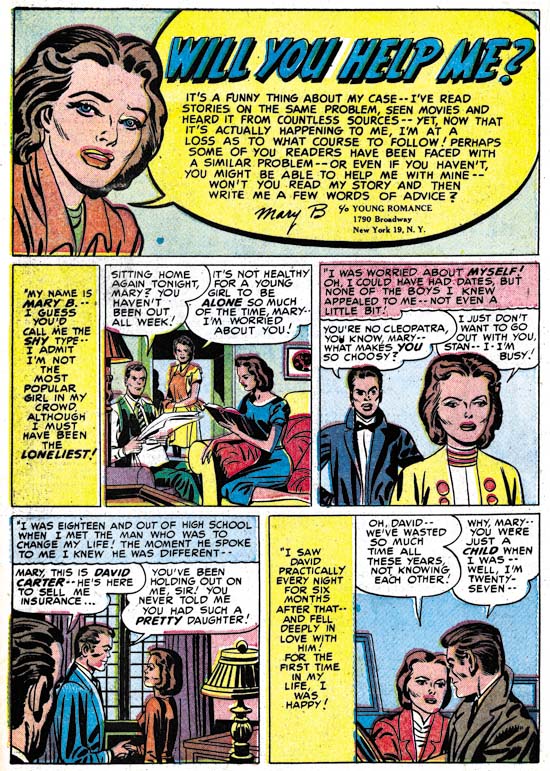

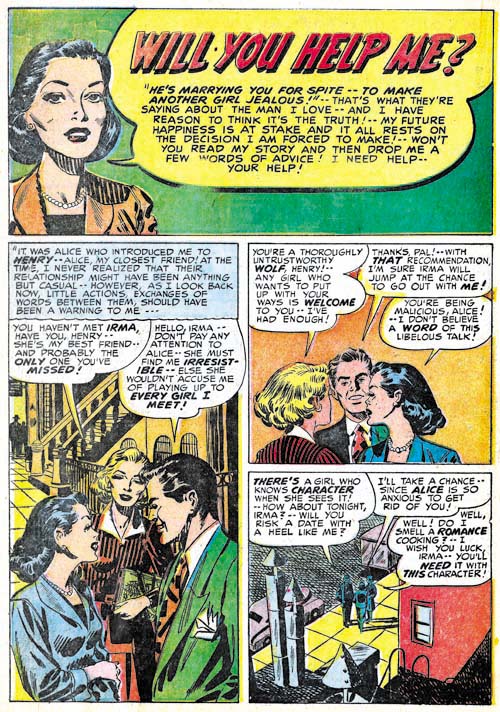

Young Love #21 (May 1951) “Will You Help Me?”, art in part by John Prentice

I must admit I am uncertain what to make of “Will You Help Me?” from YL #21. The overall simplicity of the style is different then work assigned to Prentice yet the brunette has the elegant beauty so typical of John’s work. The inking of the splash panel looks like a combination of that by Prentice and another artist. The spotting of the hair is typical of Prentice’s technique but the cloth folds are not nor are the way they are arranged along the edge of her sleeve which suggests either Simon or Kirby. The inking in the first story panel all looks like it was done by Prentice. On the other hand the crosshatching in the last story panel is not typical of any of the parties considered so far. It is possible that Prentice is inking Kirby pencils but the way the brunette turns to talk to someone behind her is a common Prentice mannerism. The other possibility is that Prentice is working from Kirby layouts with which he takes liberties in some places. It could be that John did the pencils and final spotting but that the outline inking was done by someone else. At the present I am undecided except that John Prentice participated in the art in some fashion.

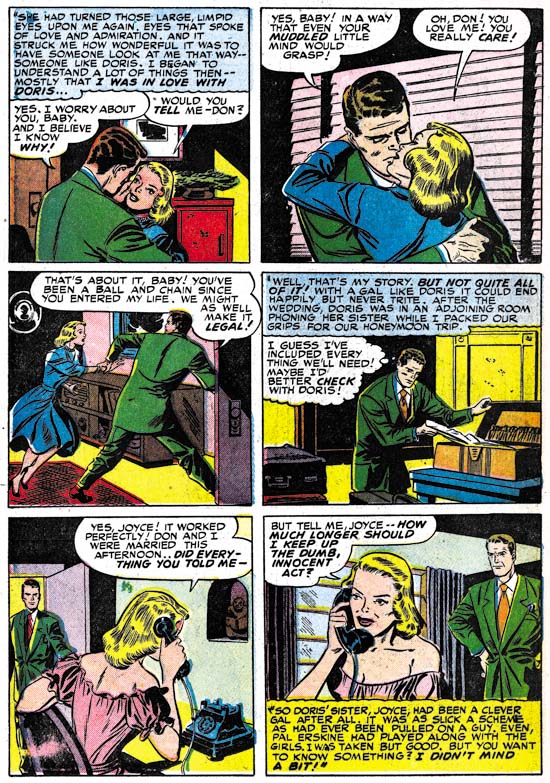

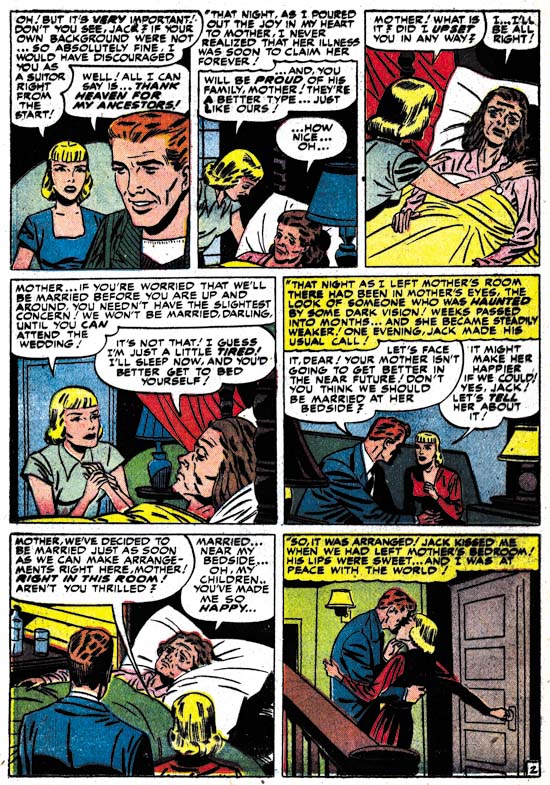

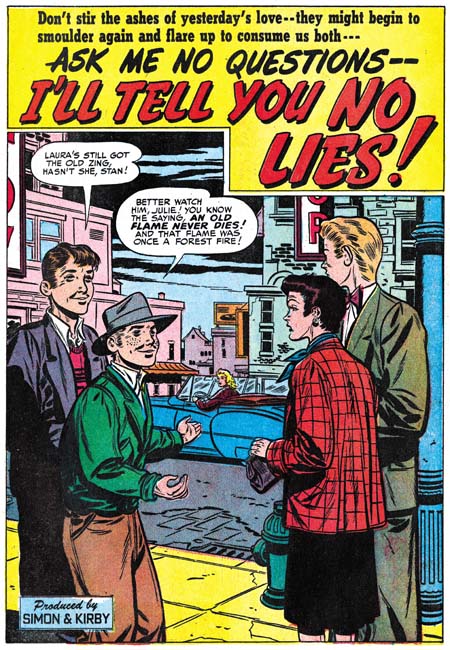

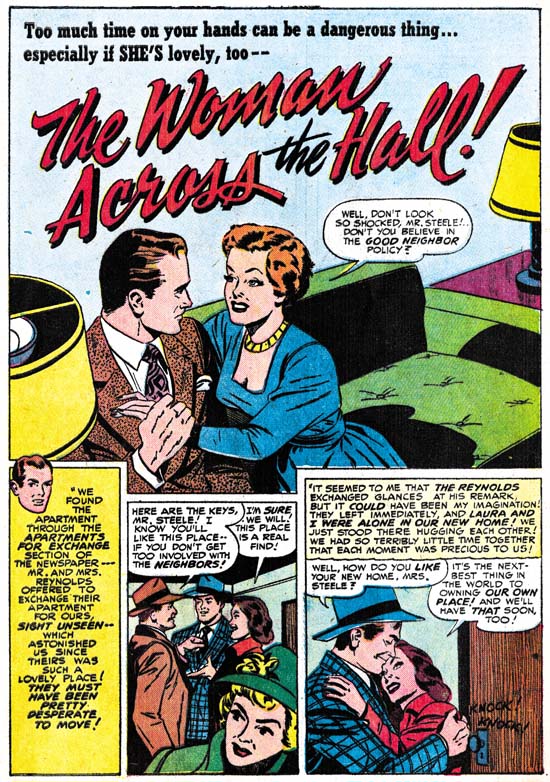

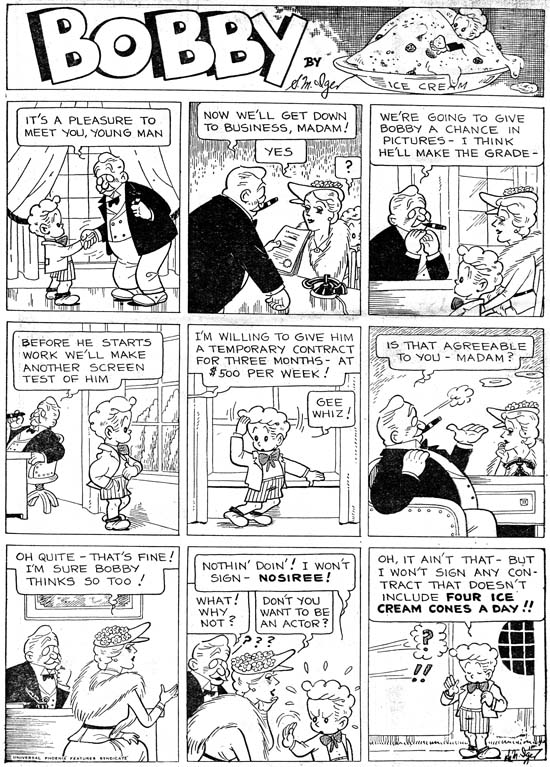

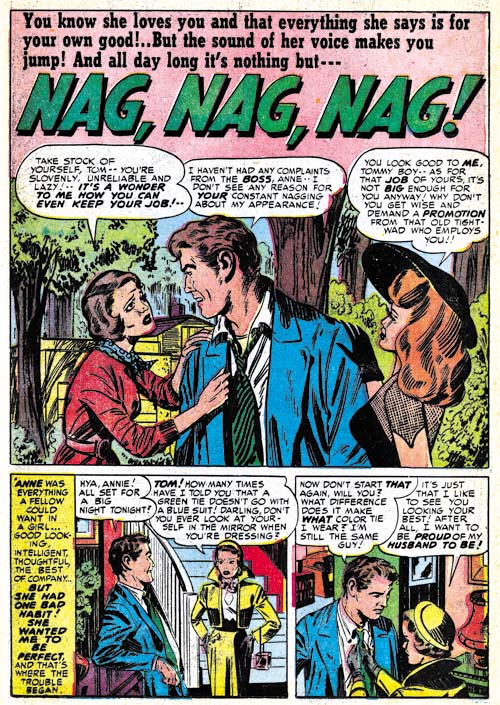

Young Love #23 (July 1951) “Nag, Nag, Nag”, art by Marvin Stein

I thought I would close off with an example of what Marvin Stein was doing during this period. The style is still typical of Stein’s early period but there are hints like the man in the second story panel that are typical of the style he would develop later.

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)