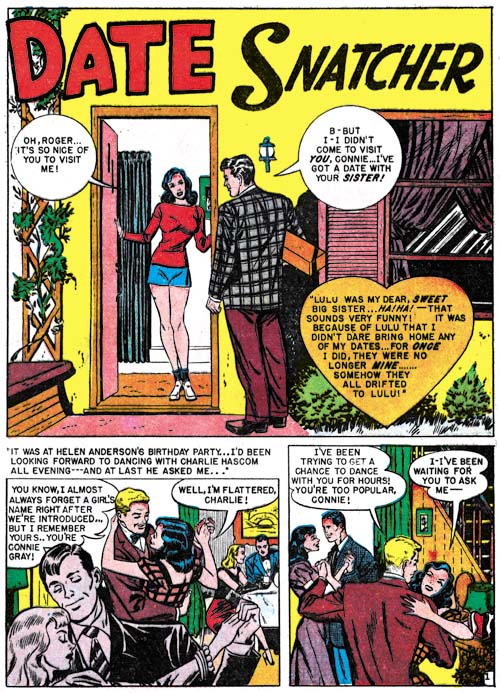

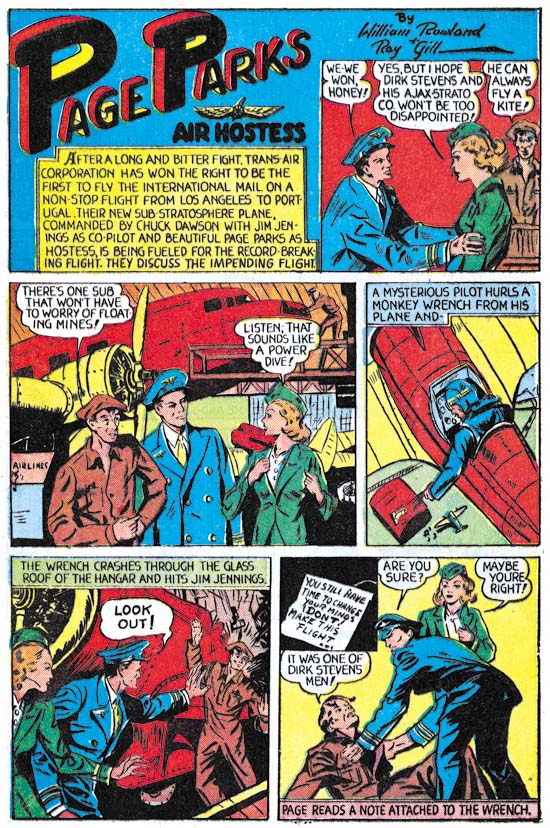

Blue Bolt #1 (June 1940), art by unidentified artist

As previously discussed, Joe Simon’s creation of the feature Blue Bolt occurred somewhat earlier than the cover date of Blue Bolt #1 would suggest. Joe supplied it to Funnies Inc. a shop run by Lloyd Jacquet that put together comic books for other publishers. Blue Bolt was just one of a number of features that Simon created for the shop. But apparently Jacquet and Novelty Press must have seen some special potential in Blue Bolt and used it as the title feature for a new comic book. Had that had been the intention all along it would be expected that Simon would do the cover art but since that was not the case we cannot assume he drew the cover. There are reasons to believe that Simon was not the cover artist and little to suggest he was. To my knowledge only the eyes of the Green Sorceress look like they might have been done by Simon. However many comic book artists found difficulty in getting eyes to sit properly on a face viewed from an angle. Otherwise none of the figures look like any other art that we can more confidently attribute to Joe. The Green Sorceress’ hair seems tamed in comparison to Simon’s depiction in the story. The dragon does not resemble the monsters in the story either. Blue Bolt’s cape lacks the distinct zigzag contour found in the story although Simon would abandon this device in future issues. Blue Bolt’s helmet includes a lightning bolt emblem that is missing from the story art. The gloves and boots have a three dimensional presence that Simon generally avoided and specifically did not use for Blue Bolt. Finally the composition is very untypical of Simon particularly the lack of any background elements causing Blue Bolt to float. It is hard to escape the conclusion that despite what some have claimed the cover art for Blue Bolt #1 was not done by Joe Simon.

Jacquet’s shop had a number of comic book artist which could have been called upon to draw the cover. Perhaps the most famous were Carl Burgos and Bill Everett but I think it can safely be said that the style of the cover art does not match either of these two artists.

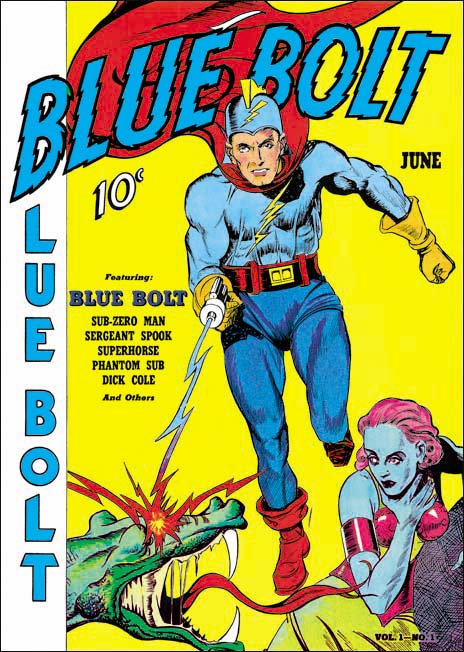

Blue Bolt #2 (July 1940), art by W. E. Rowland

Fortunately the next Blue Bolt cover was signed so there can be no question that it was drawn by William E. Rowland. The cover art for BB #2 shares some features with that for BB #1. In particular the more three dimensional aspects of the gloves and boots as well as the lightning bolt design on the helmet. I feel that the Blue Bolt’s face looks similar in the two covers. However Rowland goes even further in giving the gloves and boots a real physical presence. Further he has added details to the gloves that were missing from the BB #1 cover such as the lightning bolt and small circular shapes and lines that border the opening of the glove. While I would not rule out that Rowland was the cover artist for BB #1, I do not find the similarities strong enough to convince me that he was.

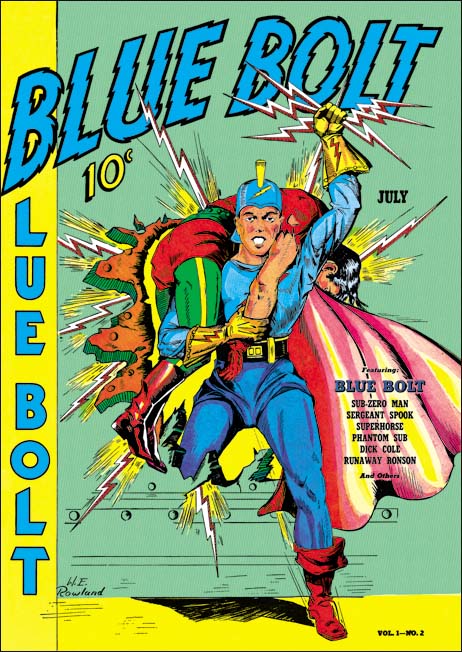

Blue Bolt #1 (June 1940) “Page Parks”, art by W. E. Rowland

The signature on the cover of BB #2 is particularly valuable because I doubt that Rowland would otherwise have been credited for the art. Apparently Rowland only worked on comic books for a few years (1939 to 1942) and even during that period he did not seem to do a lot of work. I have discussed one story by Rowland from Prize Comics #7 (December 1940) previously (Ted O’Neil). Frankly it was a rather unfair comparison of his take on the feature with Simon and Kirby’s. The purpose of the post was to highlight how radical Simon and Kirby’s work was compared to the work by more typical comic book artists even at this early stage in their career. Blue Bolt #1 also has a story drawn by Rowland and a scan of a page is provided above. Rowland is a good comic book artist, better than most contemporaries, but judging from the work I have seen so far it is hard to understand why he would have been selected to provide cover art. Whatever the basis for that decision it turned out to be a good one because Rowland’s cover art is rather nice and far superior to his story art.

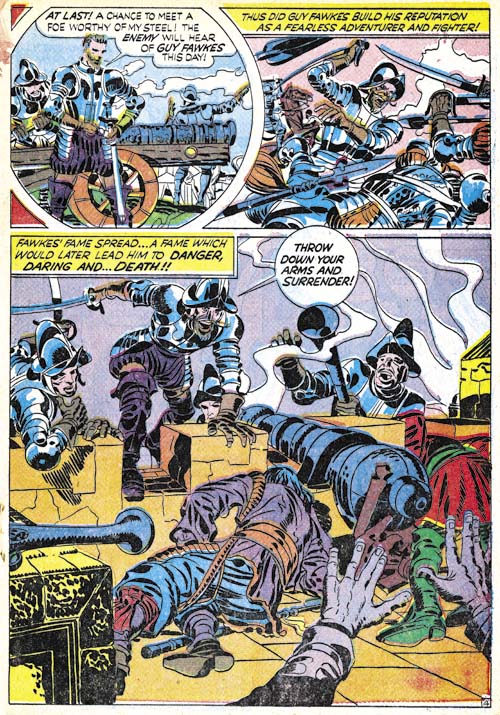

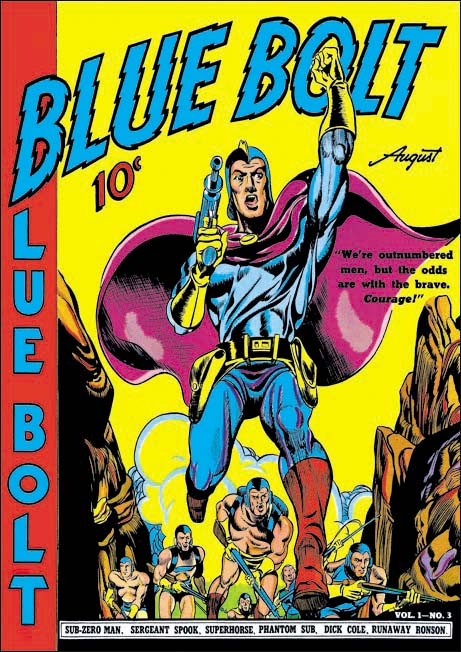

Blue Bolt #3 (August 1940), pencils and inks by Joe Simon

It was only with the third issue that Simon had his single chance to provide the cover art for Blue Bolt. Much could be said about the technical problems with the art. The cloth folds are a confusing mess and the perspective of the forward leg is not quite accurate. But these and others faults are nothing more than nick-picking that do not significantly distract from the cover’s impact. The figure of Blue Bolt was swiped from Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon (see Art by Joe Simon, Chapter 4, Footnote) but Joe has infused the figure with excitement. Simon also uses a low viewing angle so that Blue Bolt can tower over his supporting soldiers. It is a effective depiction of an attaching force coming through some mountainous pass.

There was a time that some attributed this cover art to Jack Kirby but nowadays there is general agreement that Simon drew the cover. Perhaps the most convincing evidence that Kirby did not draw the figure is the somewhat problematic nature of the perspective of Blue Bolt’s leg, Kirby’s use of perspective was always very convincing. While it is now known that Kirby did sometimes use swipes I have never seen an example of Jack swiping from the same source more than once. However this twice use of Raymond’s Flash Gordon running figure would not be unusual for Simon.

Blue Bolt #5 (October 1940), art by W. E. Rowland

Blue Bolt did not appear on every cover of the comic that bore his name. The next appearance of Blue Bolt was for issue #5 and once again Rowland has the honors. While this cover shares some stylistic features with the one Rowland did for BB #2 there have been important advances as well. Blue Bolt’s glove and boots have an even more exaggerated three dimensional look. The figures have become more massive and muscular and the inking finer and more detailed. While Rowland did a good job on the cover for BB #2, this one is a masterpiece.

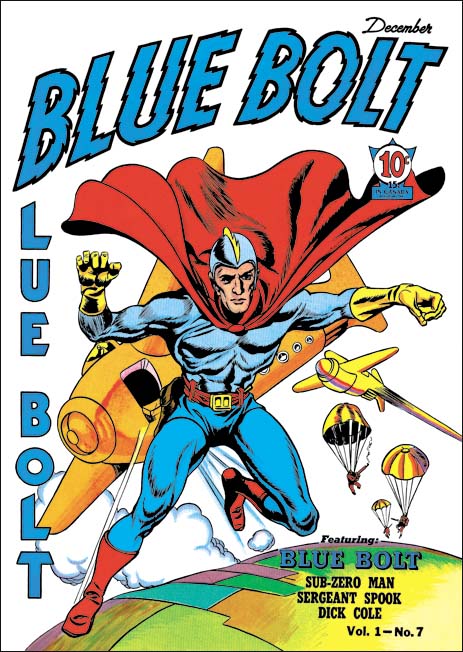

Blue Bolt #7 (December 1940), pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Joe Simon

Issue #7 marked Blue Bolt’s final cover appearance during the Simon and Kirby run. It would be Jack Kirby’s only Blue Bolt cover. While not a bad cover it was not one of Jack’s finest either. I feel much of the blame comes from the action portrayed. Jumping out of a plane just does not have the impact of, for example, attempting to stop a bomb from exploding (as seen in the cover for Champion #10, August 1940). The rather unimpressive aircraft do not help either. I am not sure what they are meant to be since they lack propellers or jet engines. Rocket planes?