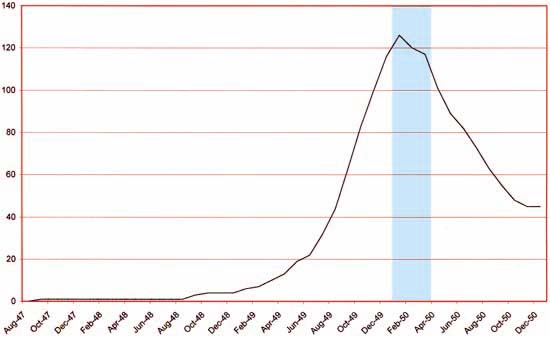

(January – April 1950: Young Romance #17 – #20, Young Love #7 – #8)

Number of Romance Titles 1947 – 1950 (the period covered in this chapter shaded in blue)

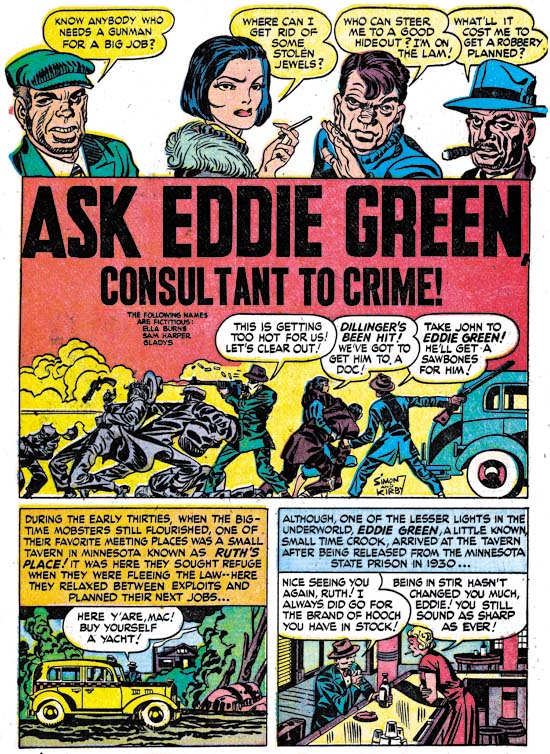

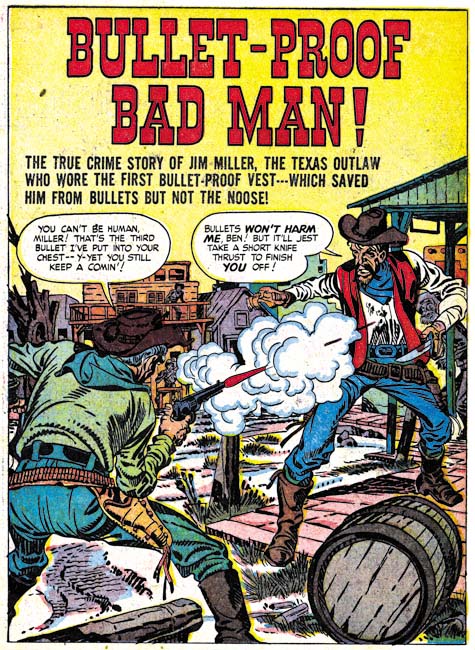

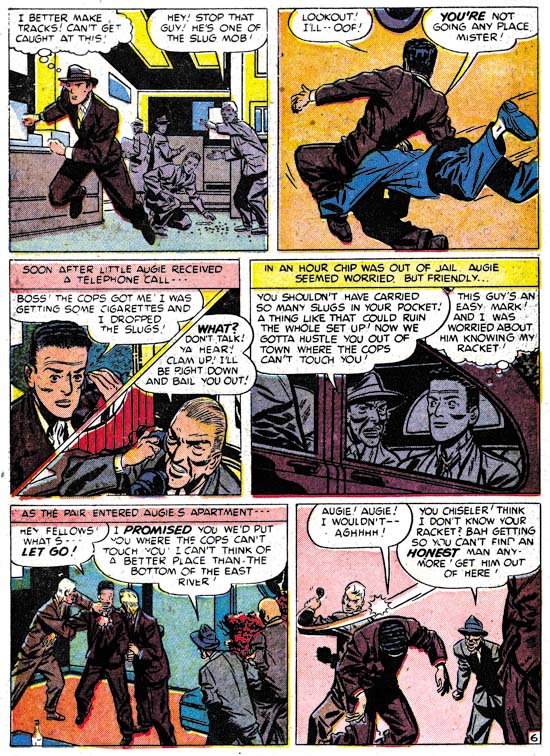

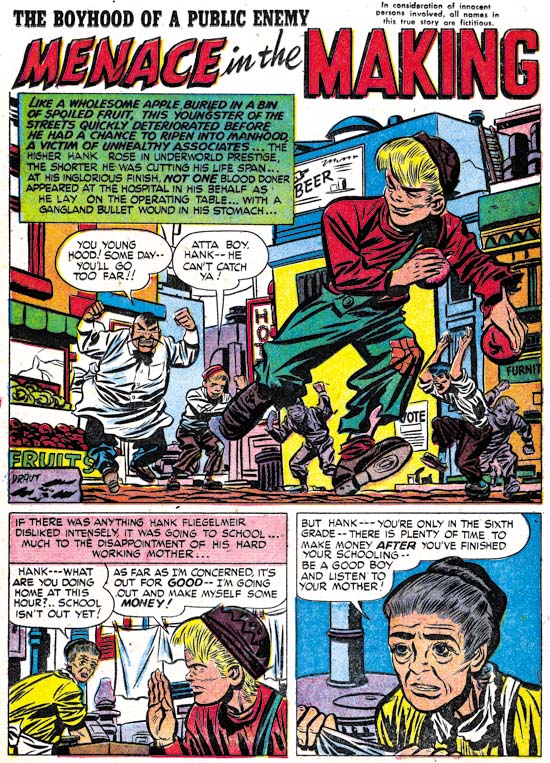

This chapter will cover the period from January to April 1950. This is the height of the love glut and the beginning of the decline in romance titles that followed. For Prize Comics the dropping of titles had not begun since the final issue of Real West Romances would come out in April. Young Romance had been and would remain a monthly. The presumably poor sales experienced by the western romance titles because of the glut was not shared by Prize’s standard love comics as Young Love became a monthly with the April issue. Frankly I am not clear what Simon and Kirby’s status was at this time with the crime titles Headline and Justice Traps the Guilty. At some point Joe and Jack seemed to have passed on the production of those titles to Prize Comics. A better understanding of exactly when that happened will hopefully be achieved as I advance further in my serial post It’s A Crime.

I have no explanation why in the last chapter Jack Kirby’s output dropped so much but now he returned to being the primary artist, at least by page count, with 6 stories and 71 pages (I am excluding illustrations for text features as they are minor works and may include recycled art.) Bill Draut, now again the second most used artist, actually had more stories but fewer pages (8 stories with 53 pages). The discrepancy is caused by the lead stories provided by Kirby have the highest page counts (13 to 15 pages). The two longest stories by artists other then Kirby were 10 and 9 pages while most were 8 pages long. As noted in the previous chapter Kirby would provide the lead story for Young Romance while Bill Draut would have the honor for Young Love. The general rule from now on will be Kirby more or less regularly providing a long lead story to Young Romance and this would be the only real distinction between the contents of Young Romance and Young Love where the lead story was generally done by other artists.

Other artists significantly trailed Kirby and Draut in page counts. The number of artists used in YR and YL drops, and the artists have been seen previously in either the standard or the western romance comics. As was true in the last chapter, Kirby did not supply layouts to any of the artists in this period. This was in contrast to the early issues where some of the less talented artists worked using Kirby layouts.

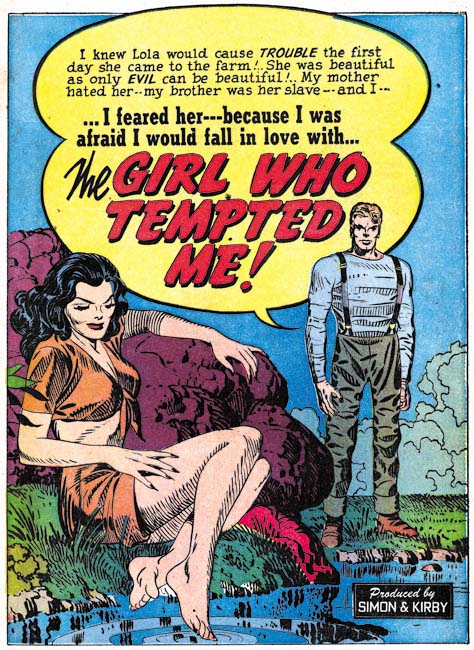

Young Romance #17 (January 1950) “The Girl Who Tempted Me”, art by Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby persists in providing exceptional splashes for his long lead stories. The use of a character introducing the story with the word balloon forming the title has become a trademark of Simon and Kirby romances. (As this splash layout will be repeatedly seen, I am going to refer to it as the confessional splash.) The very provocative splashes would be more risque then the actual story. These splashes are often very simple in composition but very effective nonetheless.

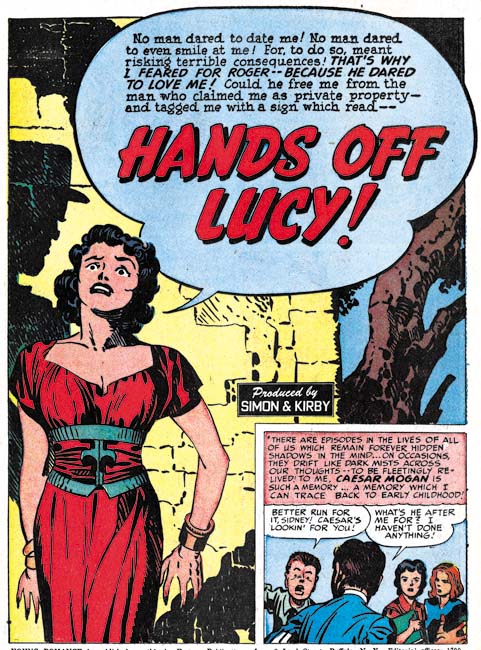

Young Romance #20 (April 1950) “Hands off Lucy”, art by Jack Kirby

Okay maybe I do not have much more to say about Kirby’s splashes, but they are so great (in my opinion) that I cannot resist including an image of another one.

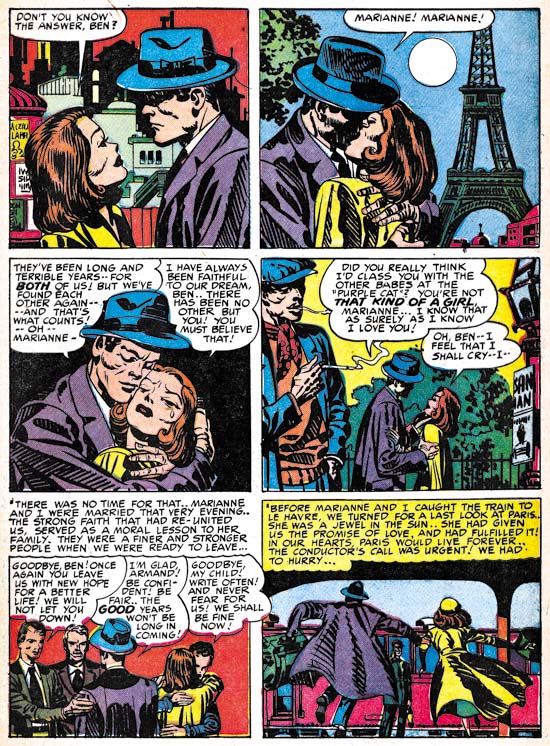

Young Romance #19 (March 1950) “That Kind of Girl” page 13, art by Jack Kirby

Of course comic books are not all about splashes, those were just the devices to entice a reader to buy the comic and read the story. Jack always considered himself as mainly a graphic story teller. Although today Kirby is primarily for his work on superheroes, he was exceptional in pretty much every genre that he worked on. Because of the unique nature of his romance stories, it is clear that Jack was not just illustrating someone else’s script. He must have been an active participant in the plotting and I am sure that he continued the long S&K tradition of changing the script as he saw fit. At this time Jack liked to give a special quality to his romance stories by adding something beyond just romance. I am not sure how the readers of Young Romance and Young Love at that time (overwhelmingly teenage girls) felt about Jack’s romances but I am convinced that if these stories were given a chance many of today’s more adult readers would find them interesting reading.

For the most part Jack has adopted a very standard page layout of three rows with two panels in each row. Kirby would occasionally depart from that pattern when the story called for it but that would be the exception. Gone were any uses of circular panels. Figures would not extend beyond a panel’s border although captions or speech balloons might. My description of Kirby’s layouts might make his work sound dry and uninspired but that is certainly not the case. Using a standard panel layout seems to allow Jack to concentrate on depicting the story. Further when the story called for an alteration in the panel layout it was then that much more effective. Kirby was a master of use of changing view points, the addition or removal of background, and even the careful accommodation of speech balloons as the above page amply shows. It was not just melodrama, it was great melodrama! (An honest appraiser would admit that was true of Kirby’s superhero work as well.)

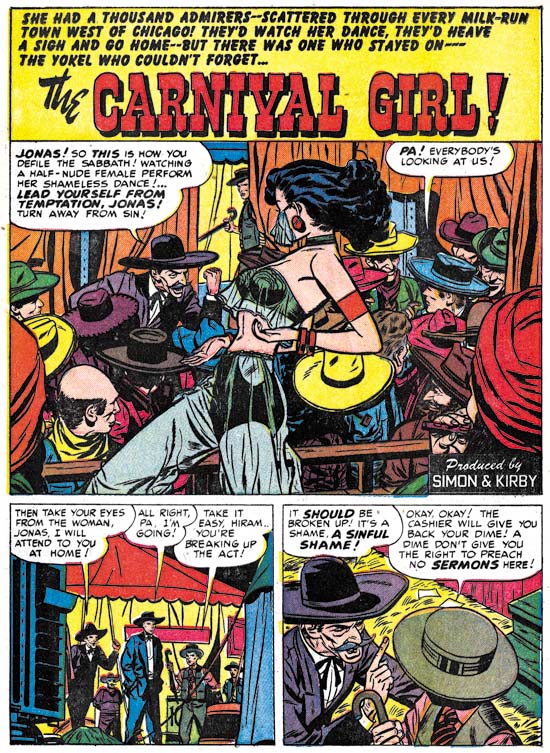

Young Love #7 (February 1950) “The Carnival Girl”, art by Bill Draut

Bill Draut’s position as the number two artist at this time was justified. He could fill a splash panel with a cast of characters each with their own distinctive personalities. Bill was no longer used as an artist in Headline or Justice Traps the Guilty, but this was not due to any problem in handling action since in his romance art he had no problems when action needed to be depicted. Perhaps of even greater importance for love comics, his women, while stylized, are attractive. All of these talents and more are shown in the above splash. Some of Draut’s stories start with a confessional splash even though they are not lead stories. Perhaps they were originally intended as lead stories but in the end placed elsewhere in the comic. Although I have seen this happen to Draut, I do not recall a Kirby confessional splash that was not the first story.

Young Love #8 (April 1950) “Every Man I Meet” page 4, art by Bill Draut

Like Kirby, Bill Draut generally kept to a standard six panel page layout. If anything he adhered to this layout even more then Jack. Bill would vary view points to keep the visuals interesting but he was not as cinematic as some other comic book artists. Draut graphically tells his story in a straight forward and understated manner. While the reader may not always be amazed by Draut’s art he will always find an entertaining and clear story.

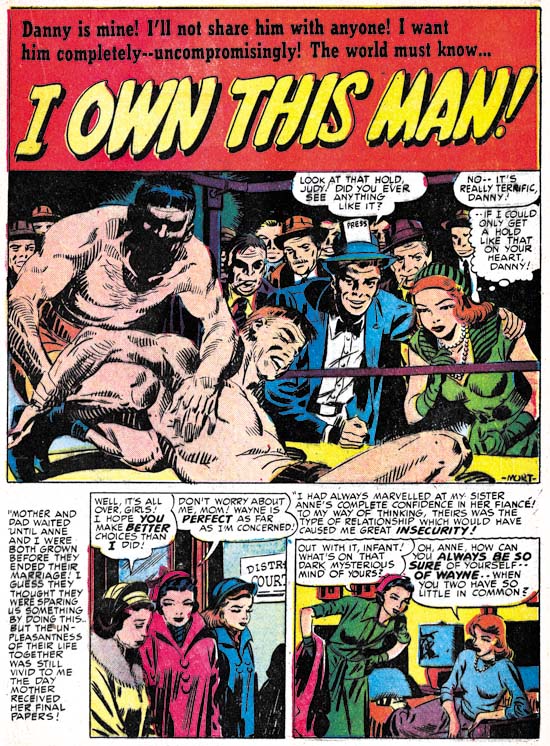

Young Romance #18 (February 1950) “I Own This Man”, art by Mort Meskin

Mort Meskin first solo work for Simon and Kirby appeared in the month before the time covered in this chapter. During this period Mort played no more important a roll then any of the other studio artists (excluding Kirby and Draut). He supplied 4 stories and 2 short features with a total of 32 pages of art. While his presence was not insignificant it was nothing like the prolific output that Mort would achieve in the future. Interestingly Mort was initially used only for the standard and western romance titles, his first crime work would be in the March issue of Headline. Perhaps Meskin’s artist block was not completely overcome by Joe’s strategy of placing random pencils marks so that Mort would not be faced with a blank page.

Meskin’s preference was for a first page; two thirds of which would be used for a splash panel leaving room for a single row of story panels. Most commonly it would have the layout seen in the image above. (Again, these splash page layouts are seen so often that providing them with a name seems a good idea; I will use square splash for those with the story panels arranged horizontally and vertical splash for when the story panels are arranged vertically.) While working in the Simon and Kirby studio Mort did his own inking. Generally this included spotting formed by long parallel, sometimes overlapping, groups of lines. Occasionally, as in “I Own This Man” Meskin would use picket fence crosshatching similar to that found in the Studio style. (For a more complete discussion of Mort Meskin’s inking technique see my post Kirby Inkers, Mort Meskin, for an explanation of the terms I am using to describe inking techniques see the Inking Glossary). My search of Meskin’s work prior to joining Simon and Kirby have so far failed to uncover any examples of the use of picket fence crosshatching so Mort may have adopted it up from Joe and Jack.

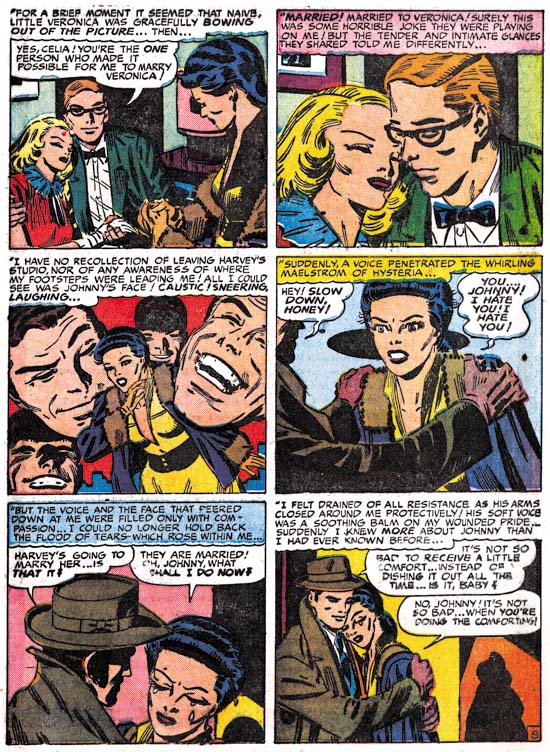

Young Love #8 (April 1950) “Danger, Soft Shoulder” page 8, art by Mort Meskin

Mort Meskin’s art was more subdued compared to his earlier hero genre comic art. Some of the more dramatic compositional devices would largely disappear. Techniques, such as the mass of floating heads used in the third panel of page 8 of “Danger, Soft Shoulder”, would now be the rare exception in Mort’s work. Instead, like Bill Draut, Meskin would concentrate more on graphically telling a story. Few other artists, if any, could do it better. Unfortunately for Mort Meskin’s current reputation, it is all too easy to overlook what he was doing. Also it should be admitted that Meskin’s art was not consistently at the same high level, perhaps a result from his push to achieve a high page production rate (with a corresponding income boost).

Young Romance #19 (March 1950) “The Fisherman’s Daughter” page 2, art by Mort Meskin

But it would be mistake to say that now Mort was only interested in telling a story. Mort was also a master at his use of blacks. The shadows found in the first panel of the page from “The Fisherman’s Daughter” shown above are very effective. Even when blacks are used in more limited amounts that are carefully placed to provide the most impact as can be seen elsewhere on the page and the fifth panel in particular. In a way though, Meskin’s use of whites and blacks was not separate aspect of his work. It was carefully used as one of Mort’s tools for advancing the story.

At this time Mort was also working primarily in the standard six panel page layout. But he would use other design techniques to add interest. Note the use of vertical caption boxes on the page shown above. Mort sets up a pattern of vertical captions for the left edge of the first and third panel rows, and the center of the second row. This while using horizontal captions in the second part of the first and third rows. It all provides a pattern that helps to pull the page together without being obtrusive.

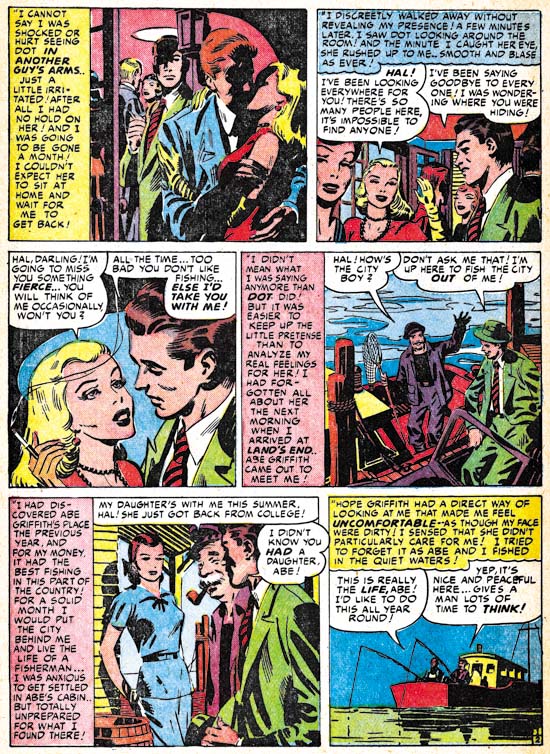

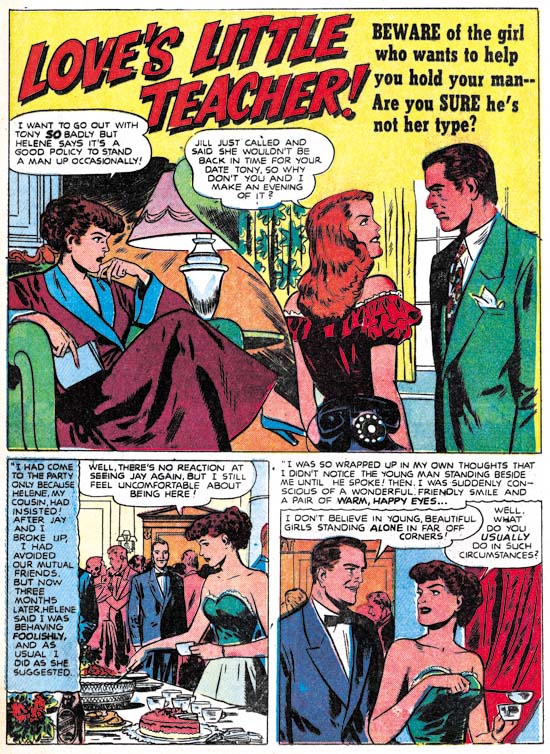

Young Romance #17 (January 1950) “Love’s Little Teacher”, art by Bruno Premiani?

I may not be able to truly show that this artist is Bruno Premiani but he is a great creator nonetheless. The splash here is unusual for him in that he provides a split scene. It is so well integrated that it is easy to overlook two separate views are presented. I have described Premiani’s women as attractive but not striking. But in the end to understand an artist’s style well enough to identify his work requires seeing enough examples. So as I continue with work on this serial post I will include further samples of the more important Simon and Kirby studio artists.

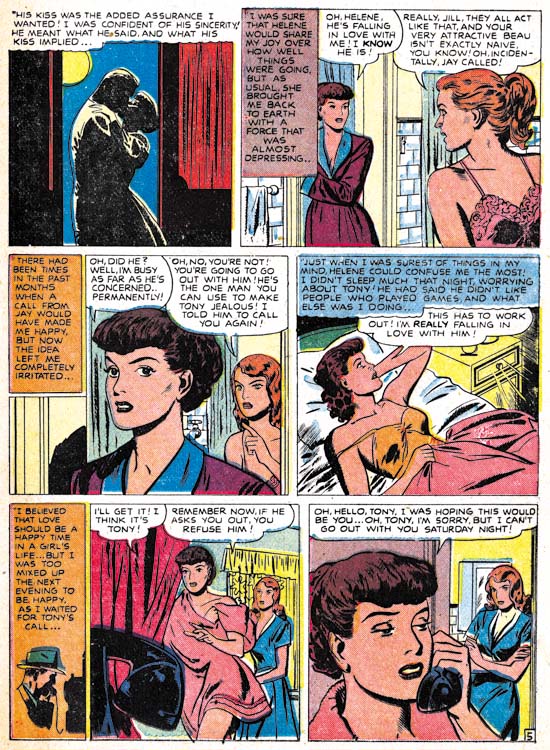

Young Romance #17 (January 1950) “Love’s Little Teacher” page 5, art by Bruno Premiani?

Bruno had an interesting drawing style but he was also, like most of S&K studio artists, adept at graphically telling a story. The page from “Love’s Little Teacher” opens with a couple’s kiss, usually more properly placed as the last panel on a page. But Premiani has other things in mind as he proceeded to show the protagonist following the advice of her cousin. Premiani indicates to the reader that the cousin is secretly scheming by the pose he provides her in the background of the final panel. Evidentially Bruno is not just following some formula but carefully brackets the cousin’s influence between the love scene in the first panel and the misguided rejection of a date in the last. I particularly like the fifth panel with the man shown calling in the caption box and the close-up of the telephone receiving the call in the actual panel. With Premiani’s careful arrangement of the towel on the leading lady, the depiction really is not very revealing but just seems so.

Young Romance #17 (January 1950) “I Want Him Back”, art by Leonard Starr

When I first entered the Simon and Kirby productions into my database I was not that familiar with Leonard Starr’s style and so it was largely stories with a signature that ended up attributed to him. Unfortunately this made Starr seem like a minor contributor since, like most Simon and Kirby studio artists, he did not sign all his art. With my current reviews and armed with a better understanding, I have been adding a number of unsigned stories as works that can be credited to Starr. I have long stressed the importance to the studio of three artists (the usual suspects: Draut, Meskin and Prentice) but there is also a second tier of artists who made an important contribution to Simon and Kirby productions but only for shorter periods of time. I would put Starr in this second tier along with artists like Premiani?, Severin, Donahue, Albistur and Brewster.

Leonard did 4 stories with 33 pages during this period. All were unsigned but with styles that are in complete agreement with contemporary signed work. Starr’s splashes were either the square or vertical layouts with, perhaps, a preference for the vertical format as seen above in “I Want Him Back”. It is the drawings of woman that I find the greatest help in identifying Starr’s work. They have an appearance that is almost frail with generous foreheads, small mouths, and narrow chins giving them a look I often describe as elfin.

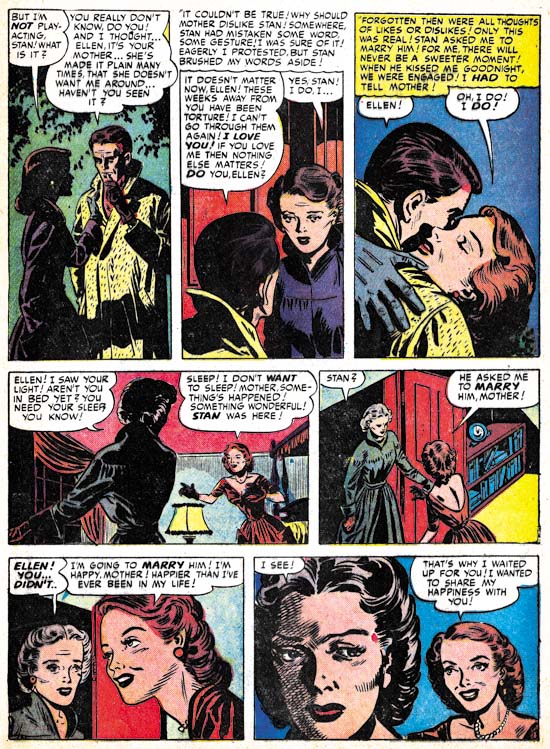

Young Romance #18 (February 1950) “Mother Tags Along” page 4, art by Leonard Starr

While I would not call Starr’s splashes spectacular they were well done. But it is his story art were Leonard really shines. Like some of the other studio artists, Starr would carefully vary the view point to keep the pages interesting and the story progressing. What makes Starr unique among the S&K studio artists at this time are his panel layouts. More then any of the other artists, Starr would break from the standard page layout of three rows with two panels per row. Instead Leonard preferred to introduced, when possible, a row of three panels with an extended height. Sometimes this was achieved by switching to a page layout of two rows with three panels per row. More frequently the greater height provided for one row would be compensated by decreasing the vertical dimensions of the remaining two rows. These panel layouts did more then provide interesting pages as Starr would use it to aid the story telling. Note how in the page from “Mother Tags Along” Leonard uses the narrow panels for the meeting of the two lovers physically bringing them close together while the more horizontal panels are used the woman’s discussion with her mother allowing the distance that is possible in these panels to suggest the emotional separation between them. No other studio artist at this time made such effective use of panel shapes although Mort Meskin would soon begin to use narrow panels as well.

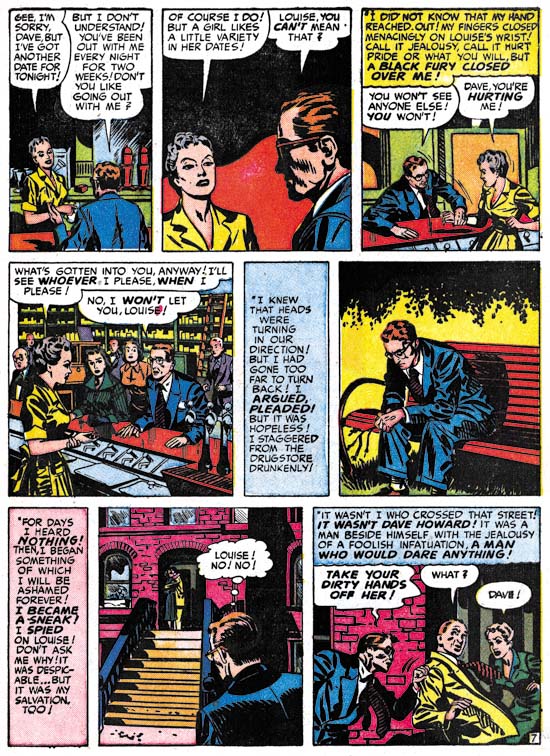

Young Love #7 (February 1950) “A Secret Affair” page 7, art by Vic Donahue

Vic Donahue’s contribution to the standard romances diminished in the previous chapter and this state continues here. There is a difference though; in Chapter 9 Vic work was restricted to the Nancy Hale feature which was 2 or 3 pages long. During this period the Nancy Hale feature was drawn by other artists. Instead Donahue would draw 1 story and 2 short features with a total of 10 pages which was well below artists like Meskin, Premiani? or Starr.

I have included the above story page to show that while Donahue was not as talented as some of the other studio artists; he was more varied in his panel layouts. I feel, however, that the handling of the story leaves a bit to be desired. For instance this page ends with one man’s confrontation with a rival. Since the last panel depicts such a critical moment the reader would expect the next page to show the result of this confrontation, perhaps even a fight. There was a fight of sorts, but at the start of the next page it is all over with the original man already defeated and on the ground! We really do not know anything about the scripts given to studio artists or how carefully they were expected to be followed, so I cannot say whether Donahue or the writer is responsible for this rather poor handling of what should have been a dramatic scene.

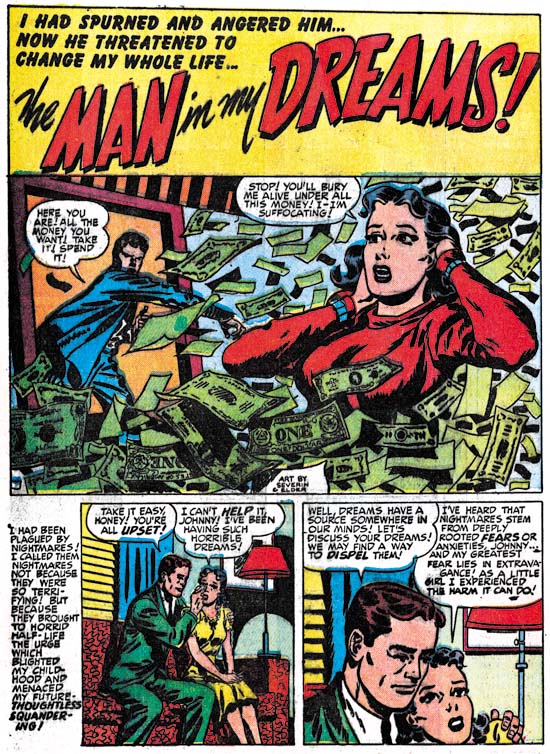

Young Love #8 (April 1950) “The Man in My Dreams”, art by John Severin and Jack Kirby

While Jack Kirby did not supply layouts for any of the artists during this period, there is at least one example of his assuming the roll of art editor. The man in the splash panel of “The Man in My Dreams” is clearly penciled by Kirby, and I believe inked as well. This is the second case of Kirby adding to or altering a splash by John Severin that I have seen (the other was in Chapter 7). If, as I believe, Kirby inked his part of the splash then most likely Kirby was correcting Severin’s finished art.

During this period Severin played a small roll in the standard romance titles. John only did 1 story and 3 features with a total of 8 pages. This is in sharp contrast to the amount of work Severin had done during this same time for the Prize western love titles.

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)