“Thou shall not desecrate art”. Okay maybe Moses did not forget to include the eleventh commandment on his tablets when he came down from the mount. And I will admit that most of the other commandments concerned more serious sins. Still alteration of art is truly morally wrong. This restriction may seem odd when it comes to comic books since that art often gets modified on its way through the publication process. However a point is reached when comic art is published (or not) and further modification should no longer be done. Some will say that when a person buys a piece of art he can do anything he wants with it. But the truth is no one really buys art, it is more like an extended lease. While the person may have possession of a piece of art, the expectation should be that someday, somehow, it will pass on to someone else. It is the owner’s duty and self interest to preserve the art for that eventual day.

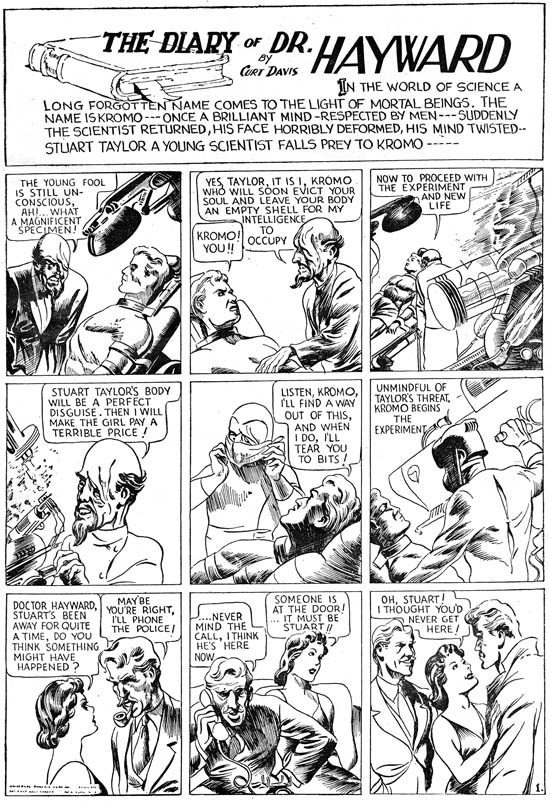

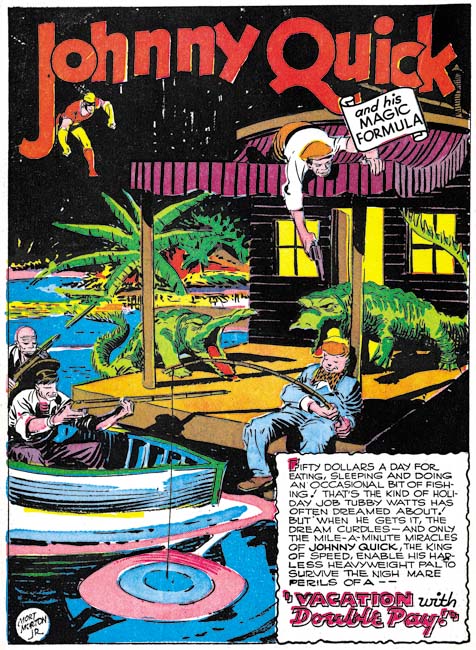

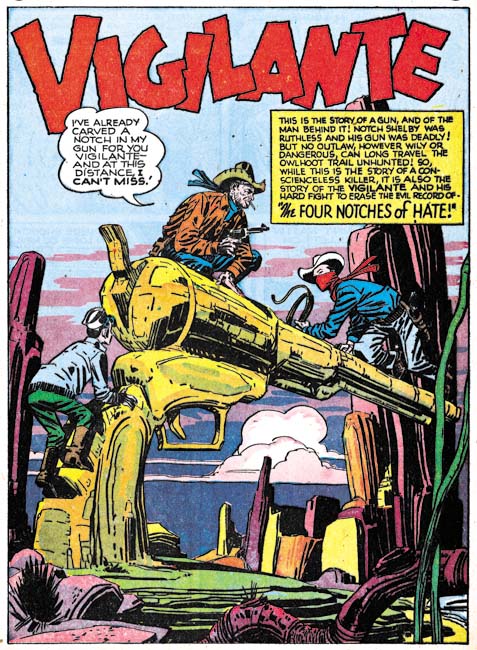

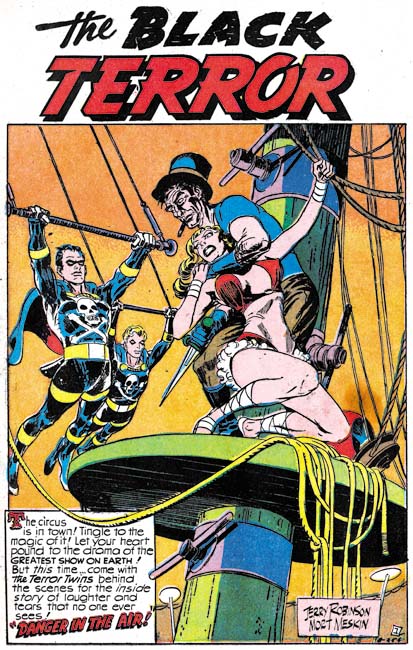

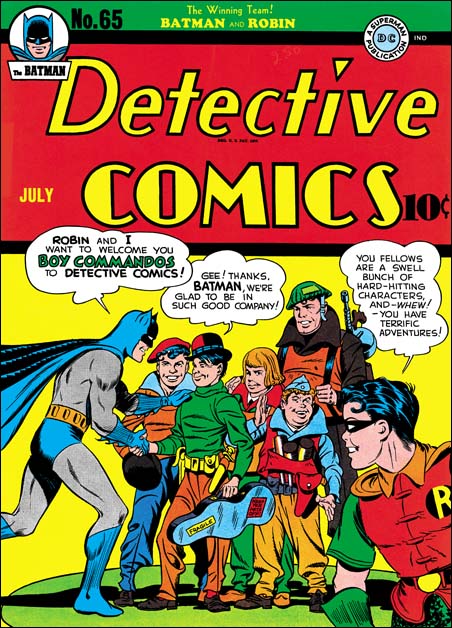

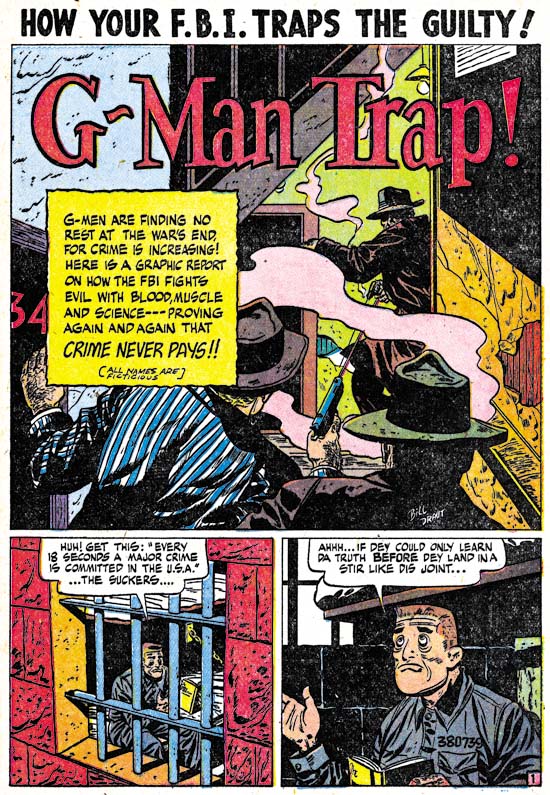

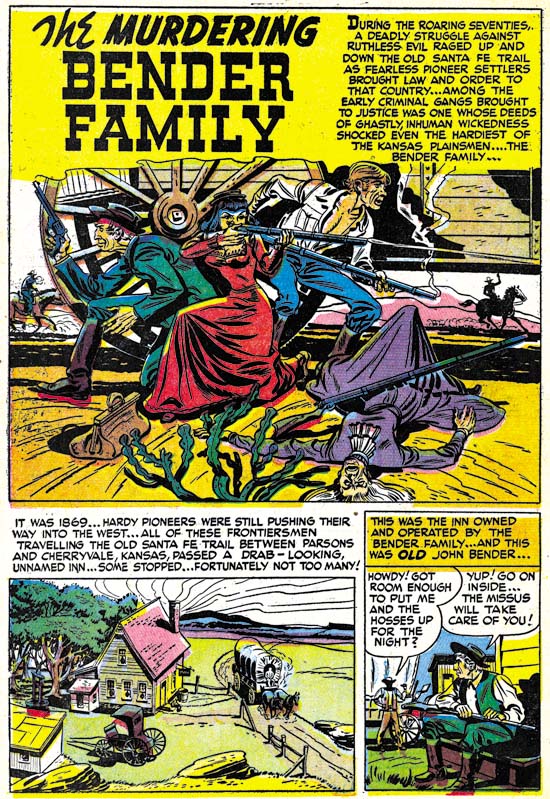

Unpublished page art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin (as published in “History of Comics” volume 1, 1970)

James Steranko’s “History of Comics” is a great resource written by a man who is both a historian and practitioner of comic books. It was published in two tabloid size volumes and is long out of print. However issues appear at conventions and sources like eBay from time to time and are well worth the search. While profusely illustrated most of the images are small in size. There are a limited number of exceptions that take full advantage of the large dimensions of the books. One of the larger illustrations in volume 1 is the source for the image shown above of a page done in pencil by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin.

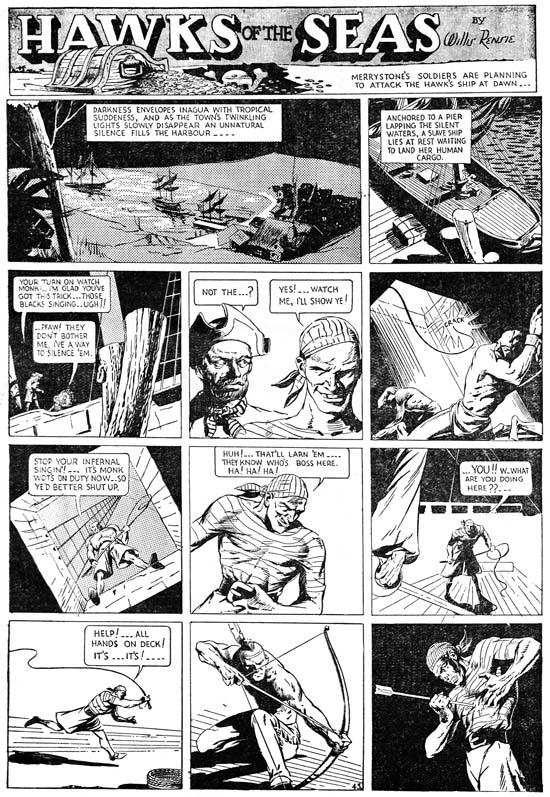

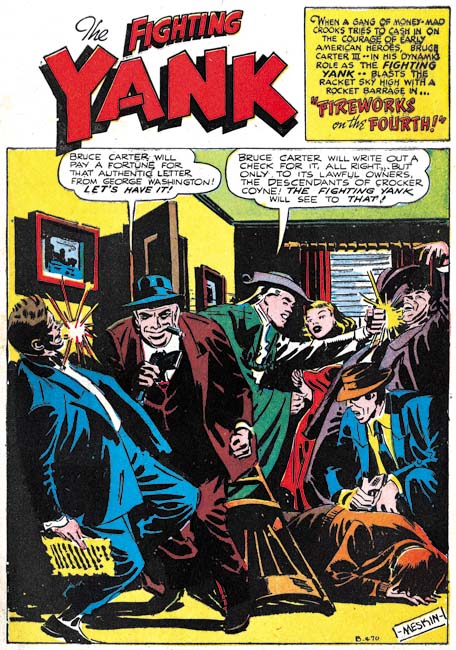

There are good reasons why Steranko gave this image such a prominent treatment. Both artists played important parts in the history of comics. Among the many contributions by Jerry Robinson is the work he did on Batman as a ghost artist for Bob Kane. Unfortunately Mort Meskin’s importance in the history of comics is largely forgotten today but is well understood by Steranko. Hopefully a forthcoming book on Meskin may help to change his current reputation. However Mort is not completely neglected for instance Ger Apeldoorn has provided some recent posts about some of his work (for example Tom Corbett Viewmaster, Real Crime and No Kid Stuff) and there is a list group devoted to him (Mort Meskin List). Besides Robinson and Meskin’s importance to the history there is the rarity of the art. Not a lot of original art for either artist has survived from early in their careers. While they shared a studio for some time they only collaborated for a relatively short period (less then two years) so examples of their joint work would be expected to be rarer still. Original art that was unpublished and left uninked are particularly rare. Last, but certainly not least of the reasons Steranko illustrated this particular page, is the quality of the art itself.

What was this unfinished page originally intended? Meskin did some marvelous work on his creation, the Vigilante, which started as a hero feature and ended up as a western. However Robinson was never associated with the Vigilante and the young man on this page of original art was clearly not the Vigilante’s sidekick Stuff the Chinatown Kid. This page of art can also be found on the Meskin web site where it is suggested it might have originally have been meant for Prize Comics Western. The period that Robinson and Meskin are known to have collaborated was from January 1948 to August 1949 (cover dates). Prize Comics was converted to Prize Comics Western with the May 1948 issue so it certainly was a possible destination for this piece. Robinson and Meskin were doing work for Simon and Kirby during this time and although I do not believe S&K produced Prize Comics Western they may have provided Jerry and Mort a connection to the editor of that title. But Robinson and Meskin’s work never be published in any issue of PCW and the solo Meskin would not appear in the title until 1956 1955. So while nothing rules out Prize Comics as the intended comic, there is little evidence to support that suggestion.

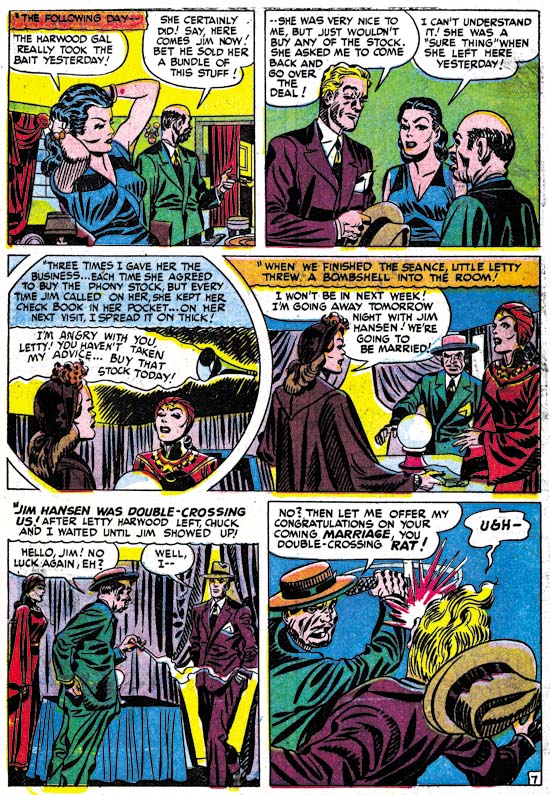

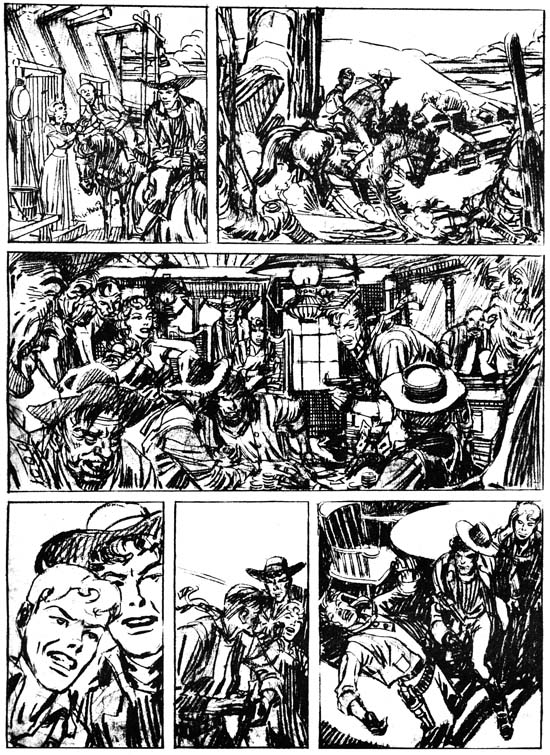

Considering the artists, it is not surprising what a wonderful page this is. The third panel is particularly marvelous. This may be the most complex panel these artists had ever done either together or individually. The panel is framed on each side by the cutoff close-ups of two smokers. A gambling game gone wrong takes up most of the panel with onlookers filling the rest. Every little portion of the panel is filled with interesting details. The only problem is where would the speech balloons go? Actually this seems to be a difficulty with much of the page with only the second and fifth panels seeming to have room for the speech balloons. The fourth panel particularly seems to call for a balloon with no place to put it. This all suggests another possibility for this page, it may have been nothing more then a portfolio piece used to show perspective publishers what the artists were capable of doing. However in the end we are left with little more then informed speculation as to the intended purpose of this unpublished art.

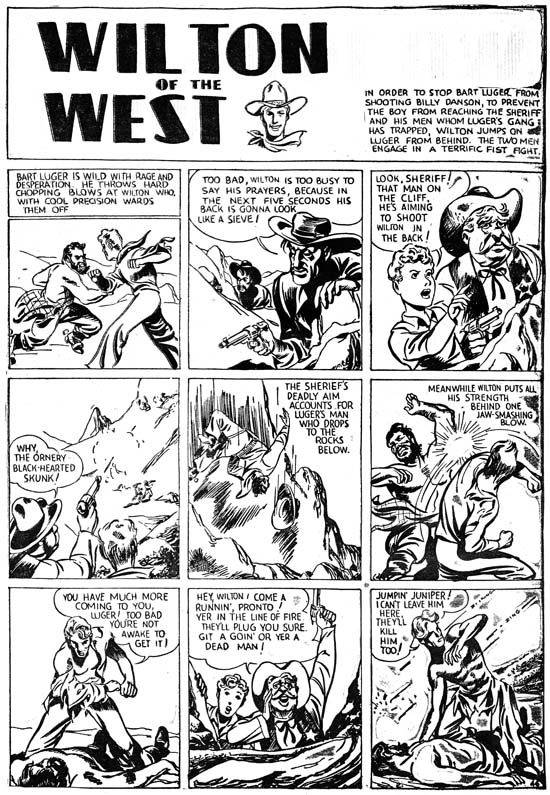

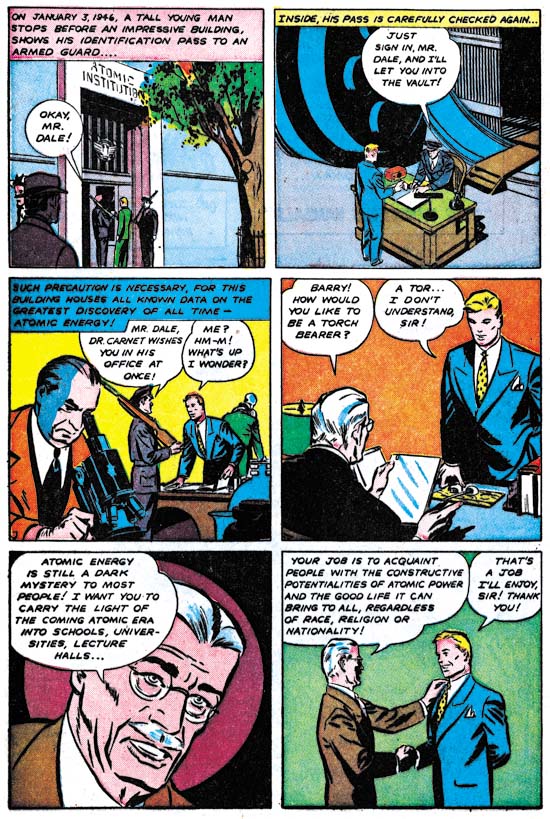

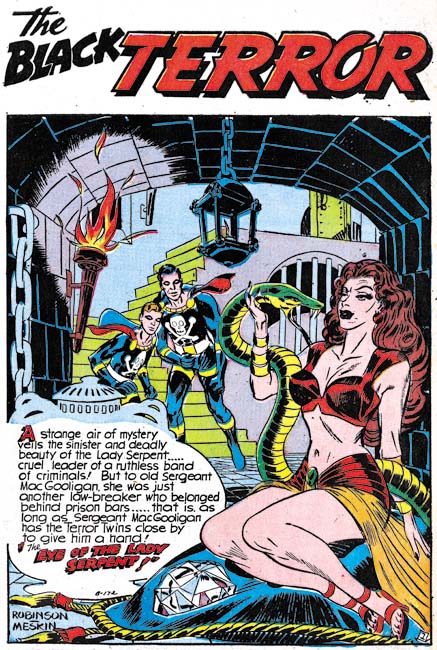

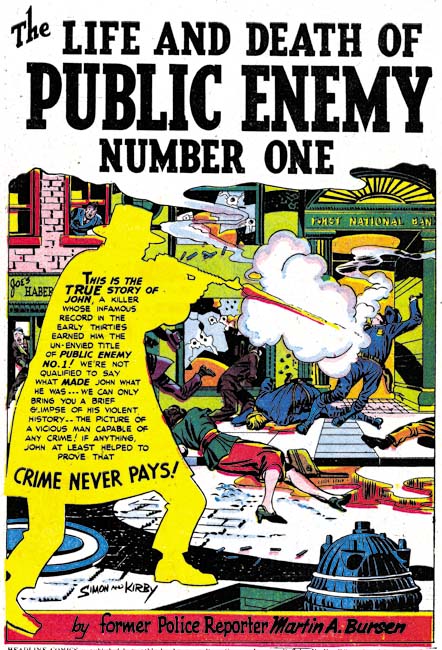

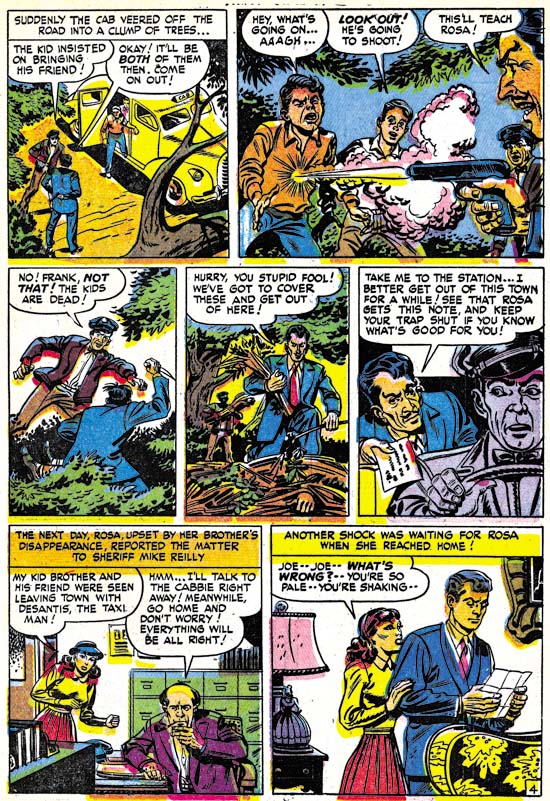

Unpublished page art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin (recent scan)

The image in Steranko’s book is just marvelous. Pencils are difficult to reproduce (which is why art is inked for comic book publication) but the image in “History of Comics” is clear and easy to see. Considering this was done before personal computers and scanners that was quite an accomplishment. Above is a more recent scan of the same art. While it may not be as clear as the Steranko’s image it does show some subtleties that the published image did not. Even here the image has been enhanced as the original pencils are lighter.

I had previously wondered what method Robinson and Meskin used when they collaborated on art since the final result looks like an amalgamation of their two styles. At least some of the inking appeared to have been done by Mort so the simplest explanation would be that Robinson did the pencils and Meskin the inking. But is the simplest explanation actually correct? The best way to answer this question is to examine uninked art such as the page discussed here. Most of the figures on the page look like they were done by Meskin with the exception of the woman in the third panel who looks like she was drawn by Robinson. That assessment is based on the style of the art but notice that the woman is drawn slightly darker then the rest of the figures. Remember this image is an enhanced scan and the difference is even harder to detect on the original art. The panel is so intricate and fully realized that I doubt that Meskin had simply left the woman blank for Jerry to fill in. To me this all suggests that Mort first penciled the entire page and then Jerry came in and altered portions. Robinson may have worked on parts of the art other then the woman but they are now hard to distinguish. I am not suggesting that this was the creation sequence that Robinson and Meskin used in all cases but it does suggest that the reason for their amalgamated style was the passing of the pencils from one artist to the other.

It is interesting how fully developed the drawing is on this page. Not only are all outlines clearly indicated but the required spotting is shown as well. For example the shadows cast by the post sticking out of the top of the house in the first frame and the shadows on the underside of all the hats. Even the cloth folds have the sweeping parallel lines that are characteristic of Meskin’s inking. Previously I felt the inking of the Robinson and Meskin pieces had been done by Mort, but perhaps Jerry also did some inking that is now hard to detect because the inks closely followed the pencils.

By now the reader maybe impatiently proclaiming “but what about the bottom row of panels”? What indeed. Because of the Steranko illustration we know that this row was originally uninked. Did Jerry Robinson, still very much active today, come back and resume working on the page? Or did Mort Meskin return to it before his untimely death? Unhappily neither is the case. A good comparison between the inked version and the one found in the Steranko illustration shows many discrepancies. Hairlines were altered and cloth folds moved. Even the outlines were not closely followed. While it is not completely clear in Steranko’s illustration, the boy on the extreme right of the last panel is cast in shadow with just enough traces of light patches to indicate the shape of the figure. Apparently this was all beyond the questionable talents of the inker who covers it all in solid black. It is true that since the silver age of comics inkers are often expected to add their personal touches, but this particular inker’s alterations have done nothing but deaden the art. Since he did not follow the pencils closely one wonders why the inking was done directly on the original art and not over some copy? Once he had finished the bottom row the contrast between it and the two upper rows must have been painfully obvious even to this inker and he finally halted his destruction before any more damage was done and the page become worthless. The page is now a monument to the wisdom of the Eleventh Commandment. Frankly even if the inker had been more talented he should not have attempted inking the actual pencils. A modern inker has modern sensibilities and his art could not truly recreate the type of inking that would have been done on this page had Robinson and Meskin completed it.