Joe Simon had accumulated a rather large collection of art. Not surprisingly many were works that he created over his long career starting when he was a staff artist for a newspaper. Also as might be expected there are a fair number of works drawn by Joe’s long time collaborator, Jack Kirby. However that does not mean, as I suspect some people believe, that Kirby material dominates the collection. Rather much of Joe’s art collection consists of work by a variety of lesser known artists. I thought I would discuss just a few of them selected for various reasons.

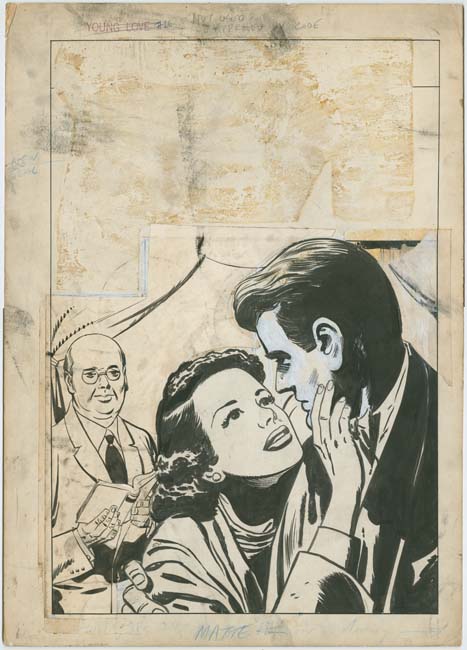

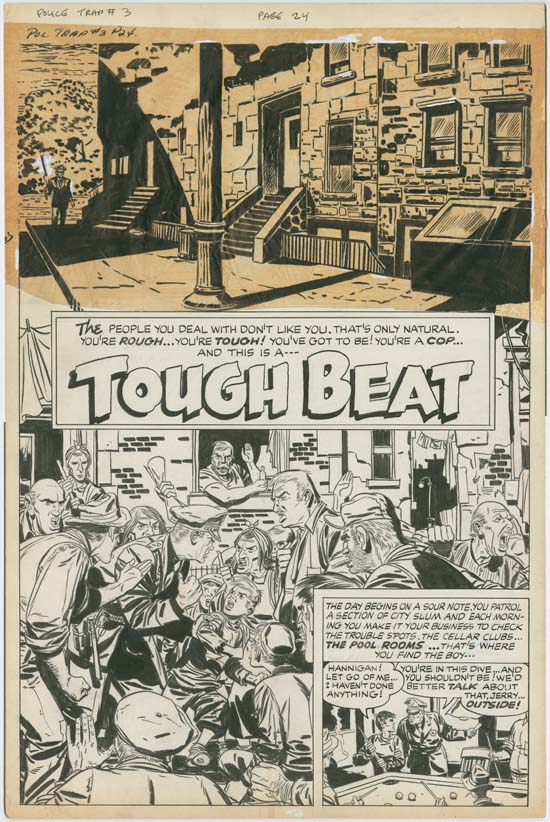

Police Trap #3 (January 1955) “Tough Beat”, pencils and inks by Bill Draut

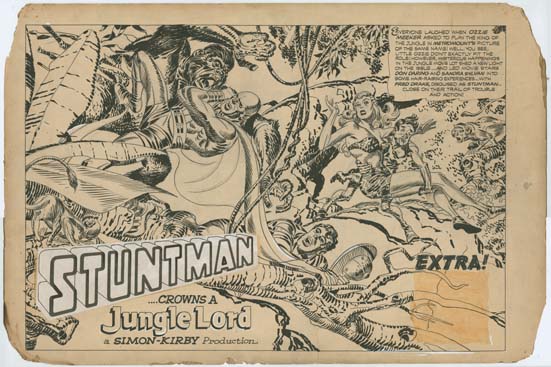

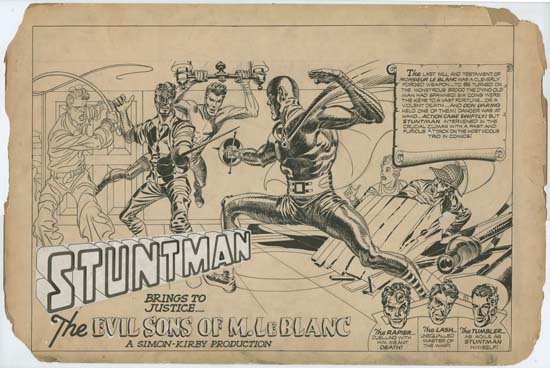

Long time readers of this blog are by now quite aware that Simon and Kirby were not just a great artistic team but also produced comic books that included work by a large assortment of artists. I have spent much time trying to identify the various artists who worked for Joe and Jack with some, but by no means complete, success. However any reader can correctly attribute the artist for a large majority of Simon and Kirby productions if they can learn to spot three particular artists. I have been fond of calling the three artists the usual suspects. Foremost among the usual suspects was Bill Draut who had a long history of working for Joe and Jack. While Draut contributed a lot of art to S&K productions, Simon’s collection only has work by Bill from three periods; from right after the war at the time S&K were producing Stuntman and Boy Explorers for Harvey Comics, from S&K own publishing company Mainline Comics, and from the 60’s when Harvey briefly tried to cash in the renewed interest in superheroes. The reason for the rather limited periods found in Joe’s collection is that Joe’s collected primarily from work on hand when a projects terminated or art he recovered years later from Harvey, Archie and DC.

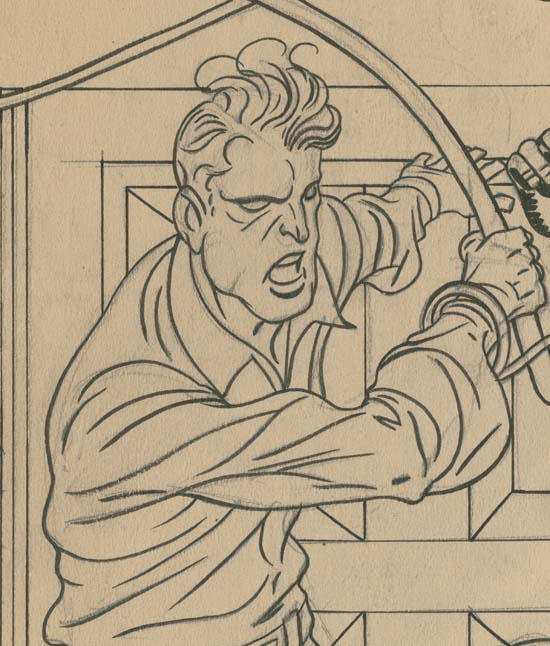

Joe’s collection has a fair amount of work created by Bill Draut and the example I provide is from Police Trap a Mainline comic book. Although Draut did a lot of romance work (as did all the Simon and Kirby artists) he could be quite adept at depicting action as can be seen in the lower splash panel. What a great assortment of characters. Note the way Draut depicts the bricks in the background building; inked as simple rectangular black shapes obviously executed without the use of a straight edge and forming small isolated groups. This manner of drawing bricks was quite typical of Draut.

It is hard to tell from the low resolution image that I have provided, but the discoloration at the top of the page is not due to some odd staining but rather the yellowing of tracing paper that has been attached to the illustration board. Bill did this as a time saving device. The final panel of the last page of the story is the same street scene differently inked to suggest another time of day. Rather than redraw the same scene, Draut put tracing paper over the final panel and inked directly on the tracing paper. When finished he just attached the results to the top of the first page.

Chamber of Chills #24 (July 1954) “Credit and Loss”, pencils and inks by Mort Meskin

Simon’s collection does not include many examples of original art by the second of the usual suspects, Mort Meskin. This is not because Joe did not like Mort’s art. Quite the contrary as shown by the fact that Joe had gathered together flats* for many of Meskin’s splash pages. This was something that Simon had done for Mort and no other artist. But the absence of Meskin original art was due to the fact that Mort did not work for Simon and Kirby during the Stuntman period and did little work during the Mainline period except for some covers (where apparently Meskin kept the original art). The one good example of Meskin original art that Joe had was not created for Simon and Kirby but for Harvey Comics. I suspect that Joe had retrieved it from the Harvey inventory some years later. It was fortunate that Simon had done so because it is, in my opinion, the finest comic book work that Meskin had ever done since the war. Great control of the story telling through devices like use of the viewpoint, marvelous drawing and superb inking.

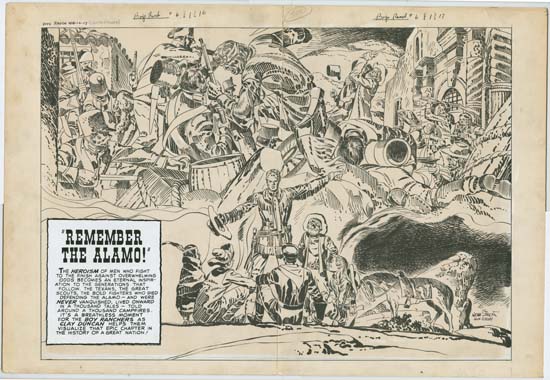

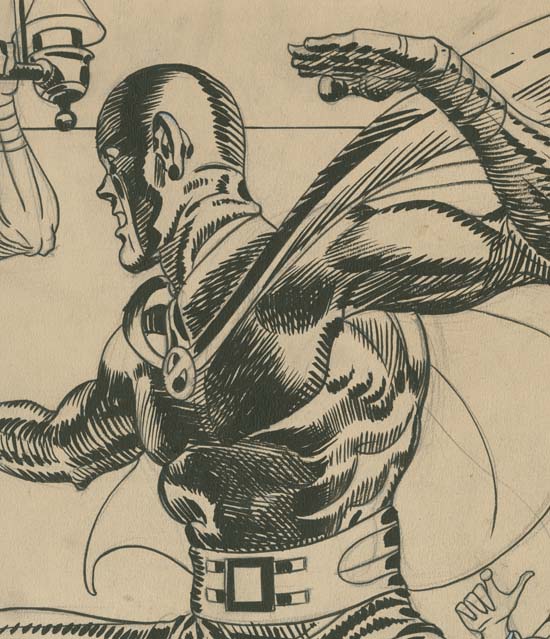

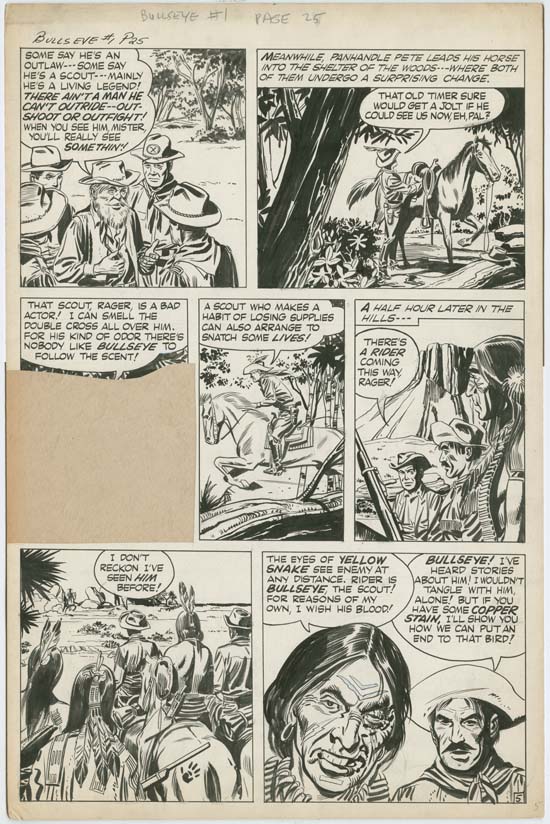

Bullseye #1 (August 1954) “Bullseye, the Man”, pencils and inks by John Prentice

John Prentice is the final of the three usual suspects. Prentice started working for Simon and Kirby even later then Mort Meskin. Joe’s collection had some examples of Prentice’s art but perhaps the most interesting is the art he did for Bullseye. There was a time that many claimed that Kirby provided layouts for the artists that worked for Simon and Kirby. One of the primary methods that I have used to investigate that claim was the way different artists used panel shapes. From that I feel quite confident that as a rule Kirby did not provide layouts for the other artists. But there are exceptions to that rule and Bullseye maybe one of them. I am not saying that Kirby provided complete layouts for Prentice’s Bullseye work but did appear to do so for at least some parts.

Unfortunately when Simon and Kirby wanted to retell the origin story for Bullseye #3 rather than redraw it Joe simply cut desired panels out of the earlier original art and pasted them together. Because of this it is not unusual to see original art from the first issue of Bullseye missing a panel or two.

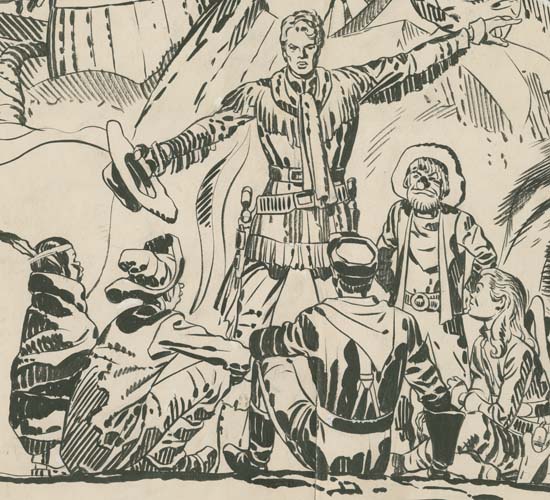

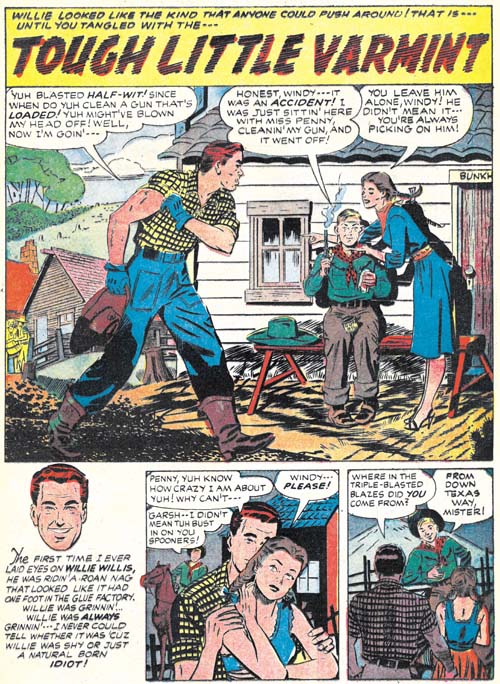

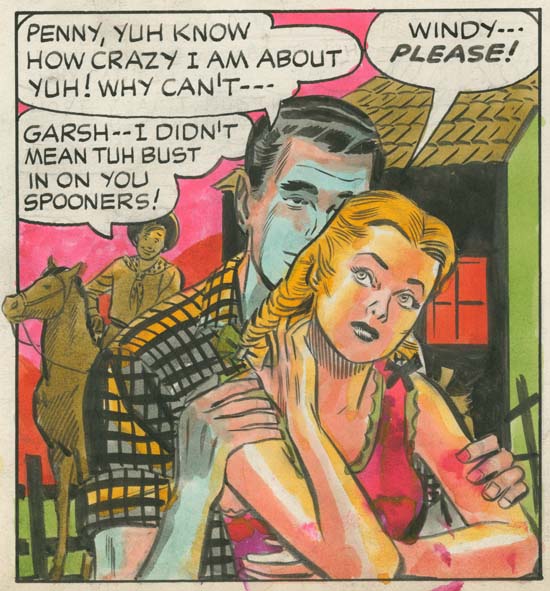

Bullseye #3 (December 1954) “The Adventures of Sheriff Shorty”, pencils and inks by Leonard Starr

Joe’s collection not only included art by the three usual suspects but other artists as well. Leonard Starr is much better known for his work on the syndication strip Mary Perkins On Stage but he also had a long career as a comic book artists included occasional work for Simon and Kirby. The example I select comes from Bullseye #3. As it was published the story appears to be unsigned but careful examination of the original art shows otherwise. The vertically oriented signature appears the bottom left edge of the splash panel. Or rather half the signature is there as the panel border now cuts through it. But enough remains to show that it is in facts Starr’s autograph.

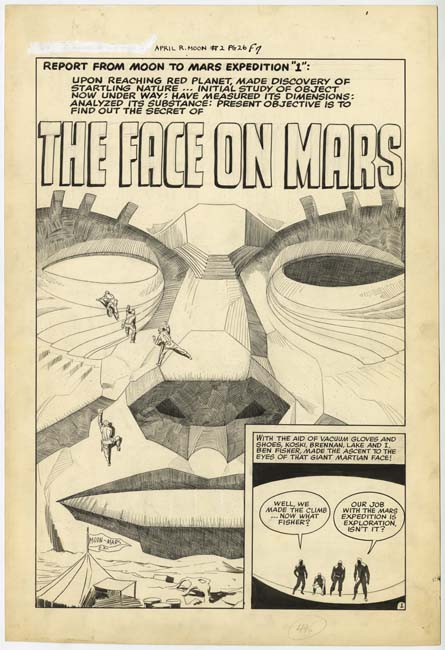

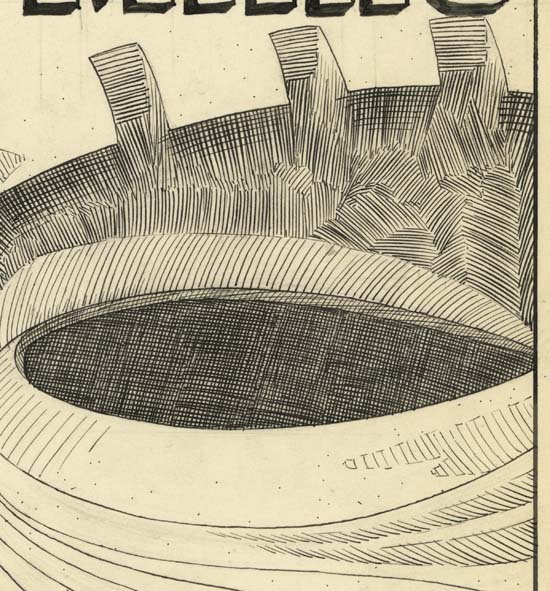

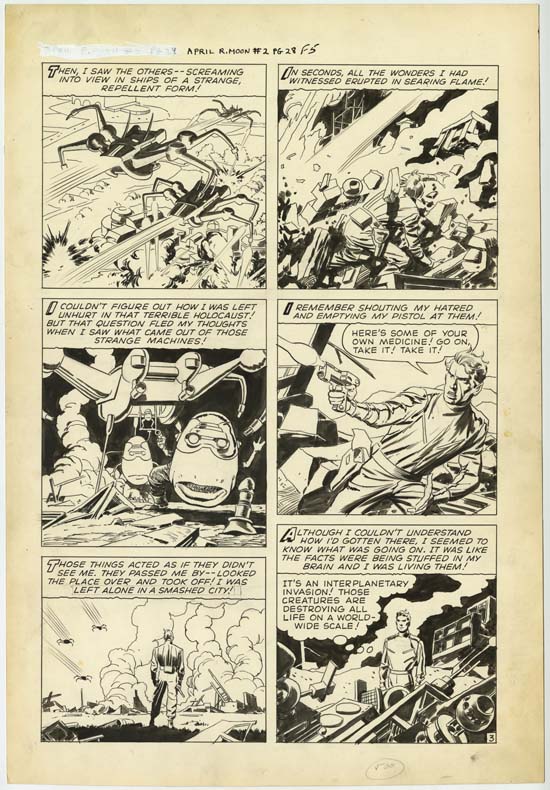

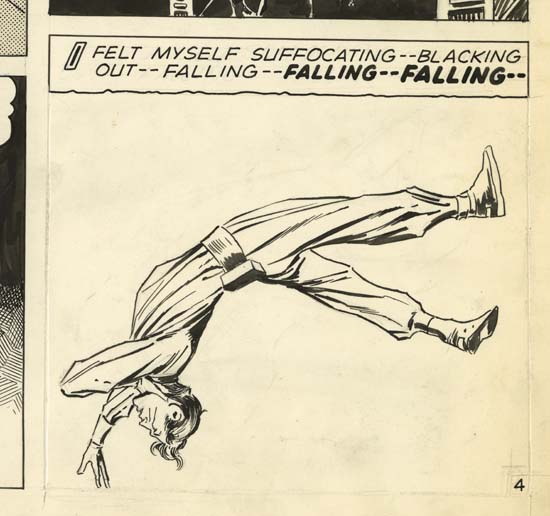

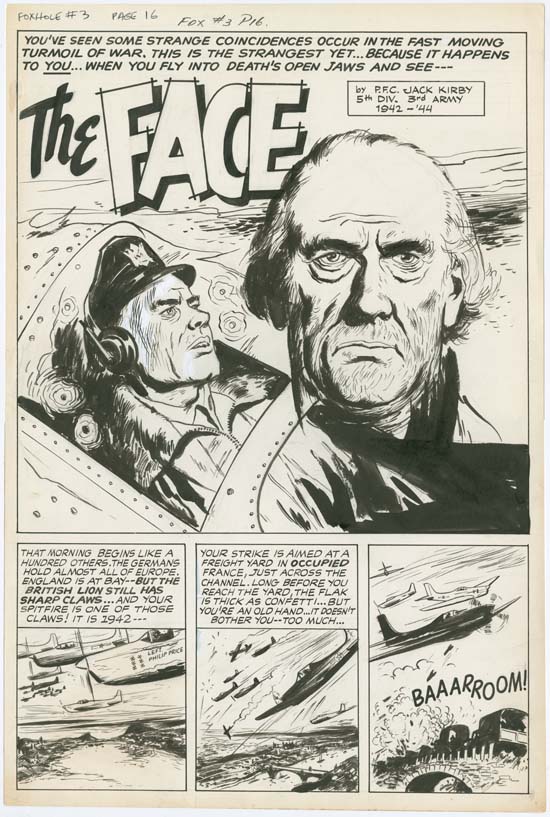

Foxhole #3 (February 1955) “The Face”, pencils and inks by Joaquin Albistur

Some artists that worked for Simon and Kirby are pretty much unknown entities for today’s fans. Jo Albistur only worked for Joe and Jack for a little over a year but produced a fair amount of art during that time. But Albistur did very little comic book art for any other publisher and only a small number of his original art have ever appeared on the market. The gimmick used for Foxhole was that the stories were created by actual war veterans. Because Albistur was from Argentina and had not served in the U. S. military, he was not suitable to receive any credit in Foxhole. But when credit was provided in Foxhole it was not always just for the graphic artists for instance writer Jack Oleck also occasionally received Foxhole credits. For “The Face” credit is given to Jack Kirby. Now Kirby certainly was a war veteran but he neither drew nor laid out this story. Further (and I may get in trouble among certain fans) I am convinced he did not write this story either. However it is known that Jack provided plots to some of the script writers that Simon and Kirby employed and perhaps it was in that capacity that this story is credited to him.

Chamber of Chills #24 (July 1954) “Grim Years”, pencils? and inks? by Manny Stallman

The Simon collection includes work by Manny Stallman. I attribute the work to Stallman with some trepidation. Stallman provided signed work for Simon and Kirby productions but when that art is carefully examined it becomes obvious that four different artists did the penciling (It’s A Crime Chapter 7, Chapter 8 and Chapter 9). Apparently Stallman was using ghost artists to pencil the work that he would then ink and often sign as his own. The work by Stallman from Joe’s collection was not created for Simon and Kirby but rather for Harvey Comics. Unfortunately it was unsigned and the pencils done in yet another style so the attribution is very provisional. But whoever penciled and inked the work the final results are rather nice.

Artists like the ones discussed in this post do not get much recognition these days. That is a shame because they really were talented artists. Now I do not want sound disdainful of contemporary artists because there is a lot of great comic book work being produced today. But let us face it, not all of them are superstars. But I am sadden that original art by secondary contemporary artists sell for much, much more than that by earlier artists. That despite the fact that relatively little of the work of the older artists has survived. It is obvious that most of today’s fans really have little interest in older original comic book art. If the reader is a collector of original art that does not share this low opinion of older work, keep an eye on the upcoming Heritage auctions as I am sure some great deals can be made.

* flats – Proofs of the line art printed on sheets in the same way finished comic book would be.