Text adapted from the visual presentation at the New York Comic Con panel, Saturday, October 15th, 2011.

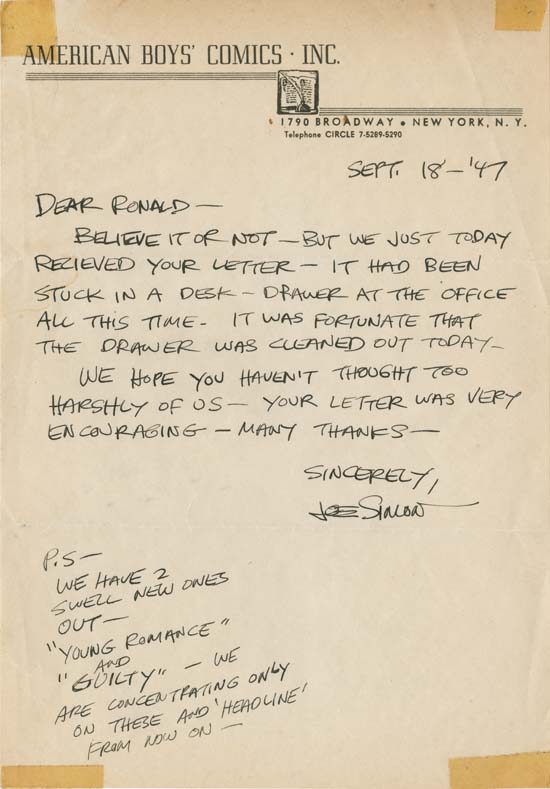

The recent court loss for the Jack Kirby estate in its battle with Disney, Marvel’s corporate owner, over copyright/ownership of the Marvel characters, revealed Stan Lee’s testimony as being the usual lynchpin in deciding the case in his, and Marvel’s, favor, that testimony essentially promulgating the same misconception that he, not Kirby, was the true author of the Marvel Universe by dint of his salaried role as editor and writer, and Kirby’s professional status as a work-for-hire employee. This misconception ignores the actual role Kirby played in the actual creation of those seminal comic books, as the auteur—author in French—of their stories. “Auteur” in the way Franco-cinemaphiles in the 1950s—first Francois Truffaut in the journal Cahiers du Cinema, and then American counterparts like The Village Voice’s film critic Andrew Harris—postulated their Auteur Theory of Film, that a film’s director, and not the screenwriter, as was previously thought, was a film’s true author.

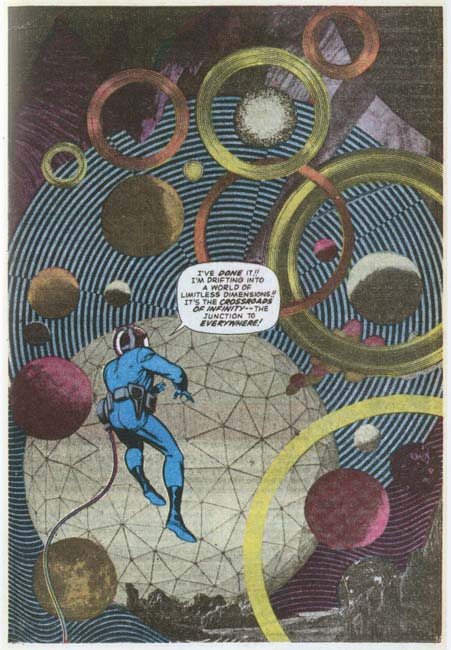

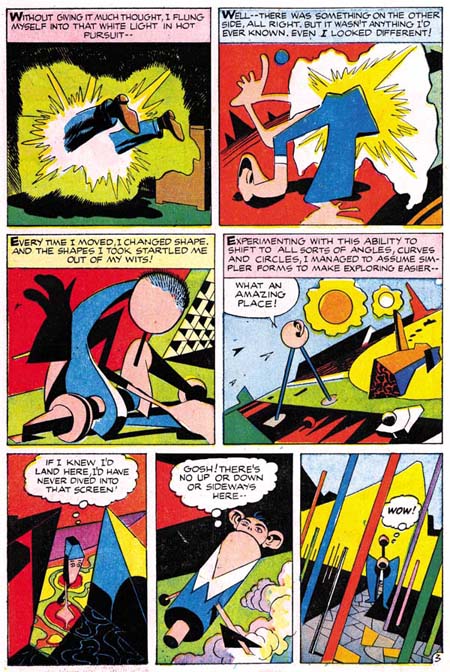

So too can the Auteur Theory of Film be accurately applied to the “Marvel Method” of comic book authorship, innovated by Lee, who gave his artists (originally and primarily Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko) anything from a typed synopsis of a story to a verbal springboard of an idea—the equivalent of the screenplay in film—and the artists drew out/plotted/staged/paced the story visually to fill the page count given, using two-dimensional versions of the same tools and devices a movie director uses to craft a film: casting, editing, lighting, sound, choreography—after which Lee would add the dialogue and captions to the artists’ work.

Stan’s interviews from the ‘60s, which stand in contrast, and somewhat of a contradiction, to his testimony in this case, were submitted in documents—eventually thrown out by the judge—during the testimony of Kirby experts John Morrow (publisher of The Jack Kirby Collector) and Mark Evanier (Kirby’s biographer); here’s an example:

“I would tell Jack the main idea that I wanted, and then we would talk about it, and we’d come up with something. I would give him the outline for the story. As we went on, and we had been working together for years, the outlines I gave him were skimpier and skimpier. I might say something like: ‘In this story let’s have Dr. Doom kidnap Sue Storm, and the Fantastic Four has to go out and rescue them. And in the end, Dr. Doom does this and that.’ And that might have been all I would tell him for a 20-page story. If the book was 20 pages long, I’d receive back 20 beautifully drawn pages in pencil which told a story. Jack would just put in all the details and everything. And then it was—I enjoyed that. It was like doing a crossword puzzle. I get the panels back, and I have to put in the dialogue and make it all tie together. So we worked well together that way for years.”

Ergo it was the artists who were the actual storytellers, not “just” the artists, with Lee, of Marvel Comics, like the directors of films have been considered the true authors of their films for over 50 years now, entitled to the benefits of credit and copyright protection of their films.

At the same time, this is not to deny Lee’s co-authorship and creatorship of Marvel Comics—he deserves exactly 50% of the credit, for his absolutely crucial contributions as editor/writer/art director/salesman and spokesman—but not a percent more or percent less. The sad fact of the matter is that Lee has successfully campaigned throughout his post-working relationships with Kirby and Ditko to create the perception—and therefore the “reality”—that he was the 100%, primary, sole creator of the Marvel Universe, relegating Kirby, specifically, to the historically demeaning role of the artist as merely a “pair of hands,” a “wrist” who robotically drew up Lee’s scripts, the only “theory”/process of comic book creation the judge was presented with.

(Comic creators like Will Eisner and Jim Steranko, who both write and draw their own work, are not germane to this discussion; they’re already 100% creators of their works. The Auteur Theory in both film and comics, as I’m applying it, pertains to those directors and comic artists who did/do not write their movies or comics, but collaborate with screenplay writers or comic writers; by dint of the act of directing a film, and drawing a comic book story, the director and the artist are the true authors/auteurs of their respective final product. The comic book works of writers like Alan Moore and Harvey Kurtzman are trickier to evaluate; for who is the auteur of Moore and artist Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen? Who is the auteur of Two Fisted Tales/Frontline/Mad? Because both Moore and Kurtzman functioned as much as art directors as writers—Moore verbally with his notorious panel descriptions and Kurtzman visually with his layouts—they’re legitimate exceptions. The overarching concept of the Auteur Theory of Comics is that it applies to any artist who does the visualizing of a comic book story, because the act of illustrating a comic book script—whether old-school full-script “DC style,” “Marvel style,” or whatever style—makes that artist a de facto auteur of the final “product” and therefore a de facto 50/50 co-creator of the work.)

The Marvel Method comic-creation working relationship of Lee & Kirby operated, in actuality, more like the Beatles’ Lennon & McCartney songwriting team; just as the early Lee/Kirby Fantastic Fours were closer to true 50/50 collaborations (see Lee’s 1960’s interview recollections and typed script/synopsis for FF #1), so too were Lennon/McCartney’s initial songs together. But as the years went on, Beatles songs became more often de facto solo projects, like McCartney’s “Yesterday,” or his “Hey Jude,” in which Lennon’s lyric, “The movement you need is on your shoulder,” is his sole contribution—essentially no different than Lee suggesting to Kirby in ’65 to have the FF fight a really big villain, and Kirby coming up with the entire Galactus/Silver Surfer trilogy (as in penciling the entire story out, and writing dialogue bits and notes in the margins). Since every Beatle song could never be perfectly quantified as to who did what, John and Paul decided early on to credit their Beatles songs to an across-the-board 50/50 split, “Lennon & McCartney,” making it easier to share in the real world of publishing credit and royalties. That’s how Lee should’ve worked with Kirby, who did the heavy lifting of actually “telling” the stories so that Lee could “write” multiple comics—the practical, economic imperative behind perhaps the greatest storytelling breakthrough in comic book history.

“That whole thing that he and Jack started was strictly for expediency because he didn’t have the scripts ready. That’s the reason. It was not done out of any stroke of genius, it was done out of expedience. Jack would call up and say, ‘Stan, I didn’t get the story yet, or the script” and Stan would say, “Ok, what I’m going to do is describe the first five or six pages in action for you, do them without words and when you send them in I’ll put the words in.’ That’s how it grew into the Marvel method of art first and script second. It was like sunlight had come into the room because this was a visual medium that had become a verbal medium for fifty ears, and suddenly it was the visual medium that it had intended to be in the first place. I think that the biggest thing Stan and Jack contributed to the industry was that. Visual first was a huge step forward; it was like a quantum leap.”

—John Romita

Yet despite this grand recollection, Stan always took full writer’s pay, while artists like Romita were never remunerated for their co-plotting and de facto writing. The most egregious example of this practice taken to an absurd degree is the famous Nick Fury, Agent of SHIELD #1 (June ’68) opening sequence written and illustrated by Jim Steranko, whom Stan didn’t want to pay as a writer because, according to Steranko, “…there were no words on the pages”! This myopia of Lee speaks not only to the primacy of word over image in both the lay public’s and the average comic reader’s—and creator’s—minds, but to the misunderstanding of the entire process of visual storytelling in comics, where the artist has control over sound as well as lighting and staging of a writer’s words; If he feels a sequence in the story can best be told silently, as in film or television, he has that paint in his palette. Theoretically, if Stan himself had written that SHIELD story—even traditionally, in full-script, with the dialogue he would’ve preferred—the auteurship of that sequence would still be Steranko’s!

Because the artist in comics has always been the auteur of the comic book reading experience, due primarily to the primacy of the visuals themselves; or, as artist Gil Kane put it once: “The only thing that makes comics worth reading is the art.” And Gene Colan said: “Every story I ever drew was like being the director of a film.” These simple statements are part and parcel of the Auteur Theory of Comics, the elephant in the room that no one wants to acknowledge: that in the verbal/visual medium known as comic books, the visual creation of a story is a de facto act of co-creation (and therefore morally and ethically entitled to all the legal benefits of co-creatorship).

Take the origin story, probably the most important component establishing the legal provenance of a comic character. Lee has always maintained, in court and out, that he created the character concepts first, and thus “created” them fully. But there was a little-known “character concept” bandied about for 15 years, called “Spiderman,” that didn’t become a copyrightable/trademarkable/successful character until artist Steve Ditko put pencil to paper and created the “Spider-Man” we know of, of stage, screen, comics, merchandise and de facto logo of Marvel, as the mouse ears are to Disney. As Ditko’s iconic Spider-Man “self-portrait” implies, a comic book “creation” isn’t fully “created” until an artist visualizes his own or a writer’s idea/synopsis/script. Which begs the question: was Stan Lee’s verbal origin story of Spider-Man more “important” in the overall/eventual success of the character than the greatest costume design in the history of comic book superheroes by Steve Ditko?

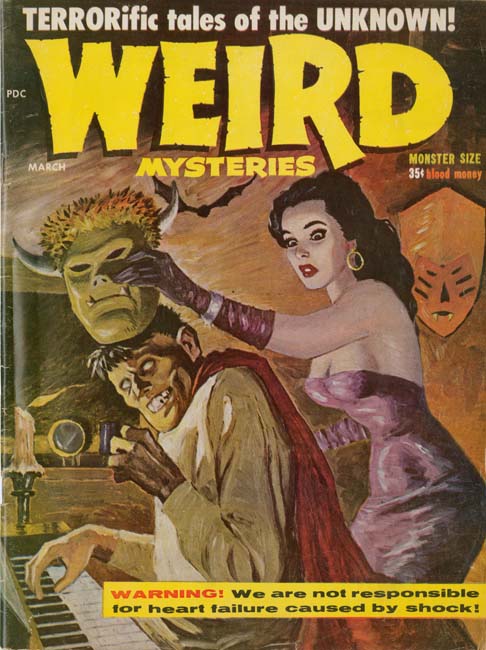

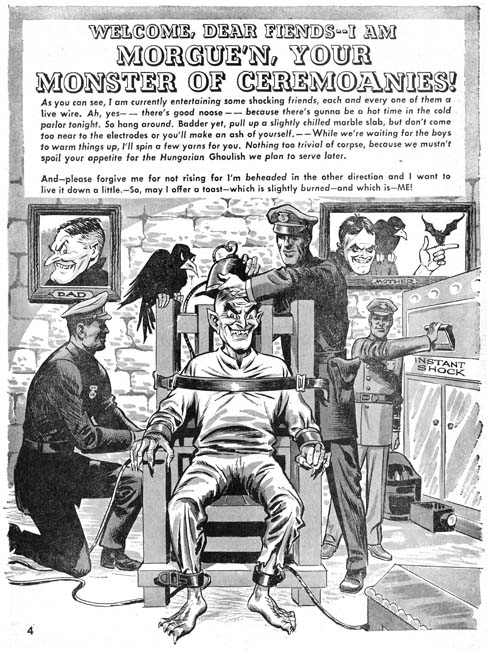

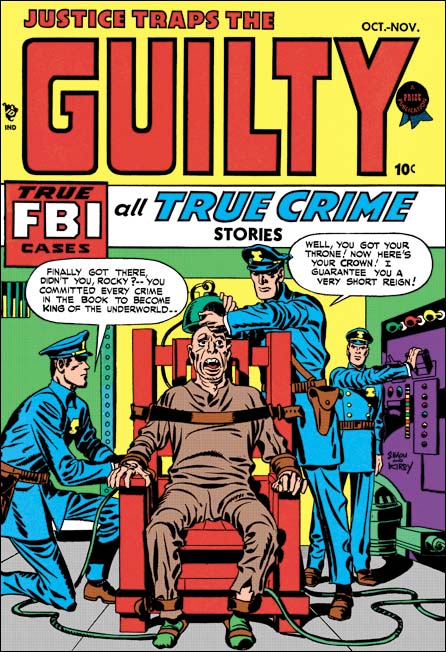

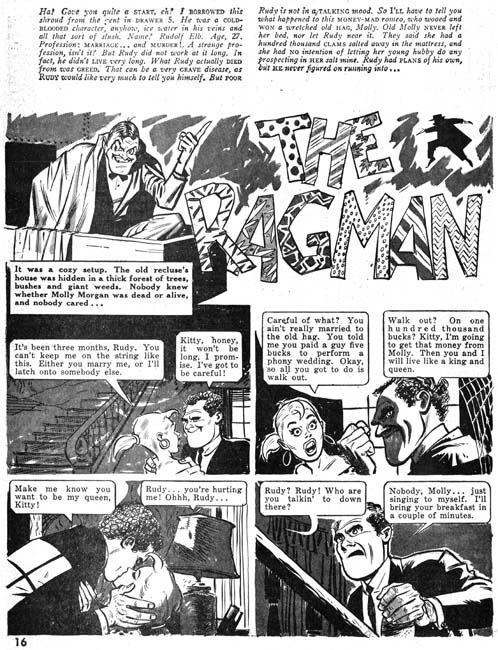

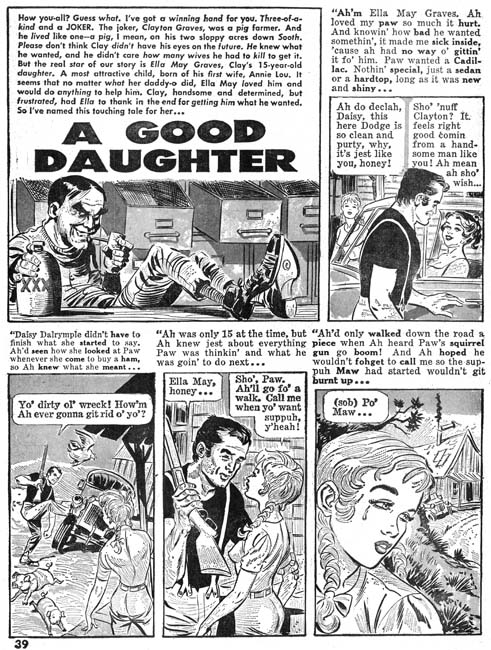

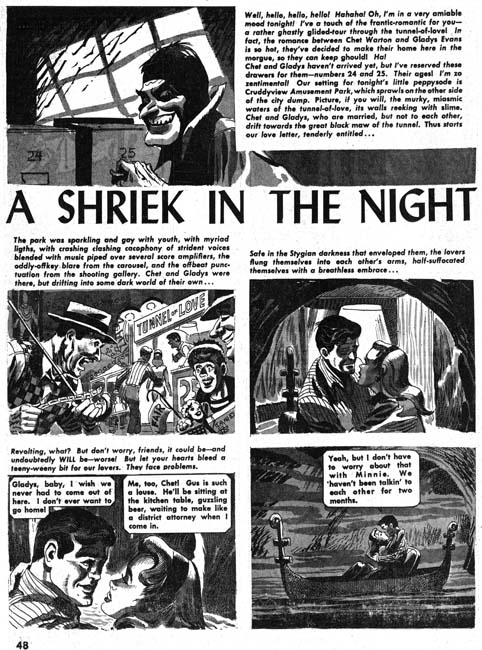

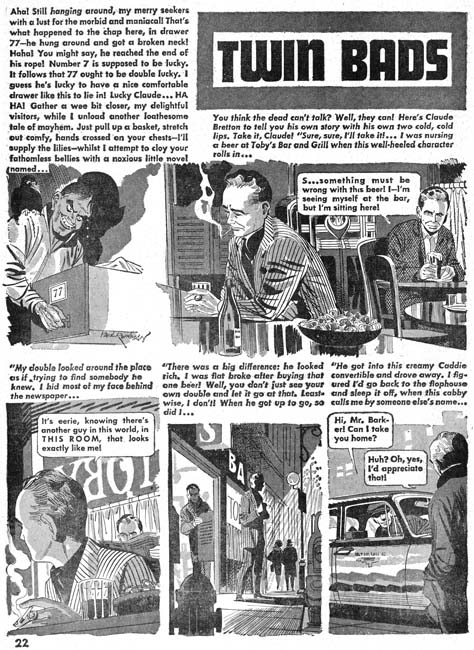

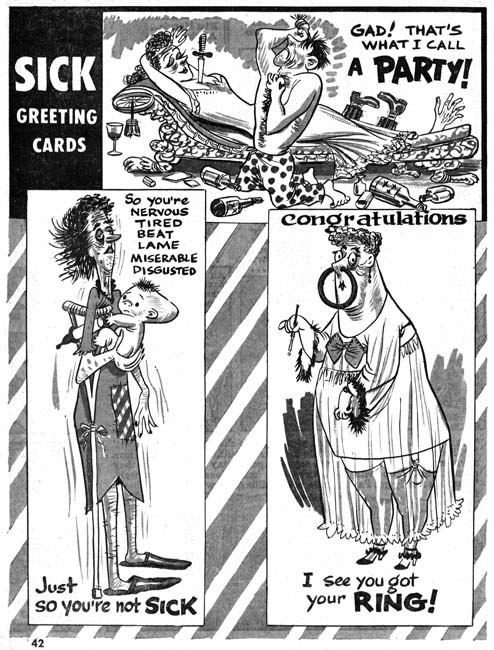

Are Gaines’ and Feldstein’s overwritten captions and word balloons to those classic EC Comics more “important” to their renown than the golden-age-of-illustration artwork that conformed to their prepared panels?

Are Bob Haney’s great 1968-69 Brave & Bold stories more “important” than the auteurism of Neal Adams’ artwork/storytelling, in which he changed all of Haney’s daytime scenes to night, just as a director of a film might alter the screenplay to more effectively work on the screen, not the printed page as the screenwriter wrote it?

Are Marv Wolman’s Tomb of Dracula concepts/writing/dialoguing more “important” to that ‘70s success story than the auteurist, atmospheric artwork/storytelling of Colan/Palmer?

When I was reading those Batman reprints from the ‘50s in those eighty-page annuals during the ‘60s, I was entertained by a raft of reprints, all uncredited, as was the DC policy then. So why did the stories illustrated by (we later found out) the great Dick Sprang stand out from the surrounding hackwork of Bob Kane ghosts? Because, despite working from complete scripts and tight editorial control (just like that of the Hollywood movie studios) Sprang’s confident, direct, exaggerated qualities that we came to love about Sprang made every story he illustrated a “Dick Sprang story,” no matter whether Edmond Hamilton or Bill Finger or whomever wrote them, because Sprang was the auteur of those Batman stories—just as the great film directors Hitchcock, Hawks and Ford, who worked from others’ screenplays within an extremely collaborative/edited/oft-censored medium, with producer control no better or worse than comic book artists had to deal with (and are still dealing with), were later declared auteurs of their films by the French film theorists.

Like film, comics are a synchronistic collaboration of words and pictures, ergo any form of a verbal script is only half of the art form known as the “comic book”—whether it’s as brief as Lee’s capsule directives to Kirby, or as extensively detailed as Alan Moore’s panel exegeses for Gibbons to follow in Watchmen.

To those who still damn Gibbons with faint praise for Watchmen’s success because, to one online poster, “a raccoon could have drawn that story and it would have been awesome,” Watchmen is, indeed, a 50/50 collaboration no matter how you parse Moore’s and Gibbons’ individual contributions, and good luck to you if you’re going to try—it’ll always be purely subjective. Moore’s Watchmen script is only worth what someone’s willing to pay to read it in its original form, just like screenplays to films are available to those who want to read them—but neither are complete artistic entities on their own. Moore himself would be the first one to admit that all of his comic book collaborations, with a who’s who of artistic greats like Eddie Campbell, Brian Bolland and Bill Sienkiewicz are equivalent in their contributions of words and pictures (hence Moore’s equitable sharing of both the legal and financials of each property). And to further diminish the line of “reasoning” that Gibbons’ “contribution” to Watchmen was somehow minimized by Moore’s gargantuan talent, imagine what a less-cerebral 2000 AD artist than Gibbons would’ve done with Moore’s Watchmen scripts—or what an average Marvel artist like Don Heck would have done with Lee’s “Have the FF fight a really big villain” idea, or what kind of costume artist Larry Lieber would’ve designed for Spider-Man!

There is a reason that Alan Moore gets more credit from the general public for Watchmen than Gibbons does; it’s why Stan also gets more credit than Jack. Literary criticism far outweighs visual/art criticism in terms of both column inches and overall impact and ubiquity, with far more literature courses taught in universities than art history. And because the graphic novel and serious criticism of comics as a visual/literary hybrid are still relatively recent—and even then, because most comics fans are not visually literate enough to actually discuss the artistic merits (and faults) of comic book art to the same degree that they discuss story/character, comics criticism pretty much follows the standard story/characters discussion, with a backhanded compliment of the “art chores” usually falling to the penultimate paragraph of most comics reviews. Combined with the fact that both the lay and comic audiences know far more about traditional “art”—painting and sculpture, and now computer graphics—than they know about how comic book art is actually produced, and you have the current situation, in which Stan Lee is thought of as both the writer/creator and the artist of Marvel Comics! Want proof? From a recent issue of Comic Shop News (#1259), by Cliff Biggers & Ward Batty in cooperation with newsarama.com:

“Comics icon Stan Lee, creator of the Mighty Marvel Universe and characters such as Spider-Man, Incredible Hulk, X-Men, and Iron Man…”

Think of this Auteur Theory of Comics being the testimony in defense of Kirby that could have/should have followed Lee’s entirely self-serving testimony, enlightening the court, the media covering the trial, comic book readers and the general public to truly understand, maybe for the first time, the role of the artist in the de facto co-creation of a comic book work, and to the truth of the Marvel Method in actual practice, asserting an artist of the magnitude of Jack “King” Kirby his morally and ethically rightful place as the auteur of the Marvel Comics Universe.