Jack Kirby had a lot of different inkers throughout his long and productive career. During the time of Jack’s collaboration with Joe Simon, most of his inkers were also artists that worked for the S&K studio. Mort Meskin, for one, had a extended and fruitful association with Simon and Kirby. The earliest S&K production that included a Meskin signature was “The Inferior Male” from Young Romance #6 (July 1948) (see previous posts here and here). That particular piece was also signed by Jerry Robinson, the usual assumption is that the first signature (in this case Robinson) was the penciler and the second (Meskin) was the inker. Here support is found in that at least some of the pencils do not appear to by Mort, while the inking is typical of his work that follows. The first work to be signed by Meskin alone came over a year later with “His Engagement Ring” (Young Romance #16, December 1949). There is an even earlier work then both of these that Meskin at least participated in (“Love Or A Career” in Young Romance #3 January 1948). To be honest I am holding back some information that I want to be the subject of my next week’s post. Although Mort’s earlier work for Simon and Kirby was sporadic, from 1950 on he became the most prolific of the studio artists. During this time Meskin’s output may have even exceeded Jack Kirby’s.

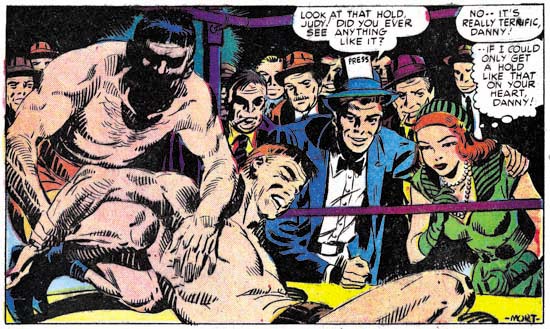

Young Romance #18 (February 1950) “I Own This Man”, pencils and inks by Mort Meskin

I provide above a splash by Meskin from early in his association with Simon and Kirby. It gives examples of a number of Mort’s spotting techniques. Mort’s most common brush method, actually used much more frequently than apparent in this splash, is to describe clothing folds by using two or more narrow brush lines in close or overlapping paths. These can be found in the pressman’s blue jacket. Note how what the original individual brush strokes are sometimes revealed at the ends of the folds. Another Mort inking style was to often distinctly outline shadows. Once again this splash does not provide the best examples but two of them are present one near the center of the wrestling mat while the other is near Mort’s signature. The wrestlers give Meskin the opportunity to do some real nice simple hatching. The lines vary from thin to quite bold. Often one and occasionally two lines are used to delimit a hatching area. This type of brushing technique is very reminiscent of the S&K Studio style picket fence work. (See the inking glossary for an explanation of my inking terms such as simple hatching and picket fence). I do not know enough about Meskin’s prior inking to say whether this is typical of his work at the time or if this shows he was influenced by the Studio style. The dark spot on the reporter’s right shoulder are suggestive of the Studio style’s shoulder blot. That is misleading as Mort always seems to use these in a way to suggest realistic shadows while in the Studio style they generally appear on both shoulders without any natural explanation.

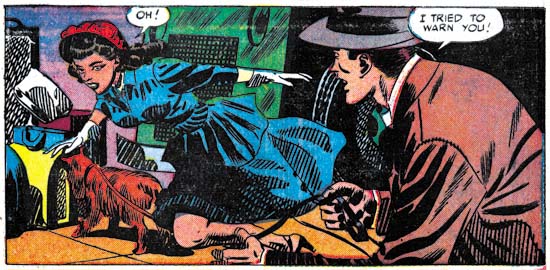

Young Romance #37 (September 1951) “Just to be Near Him” page 2 panel 1, pencils and inks by Mort Meskin

Although it maybe debatable whether my first image represents true Studio style brushwork, later work can certainly be called that. In the above image the pickets of the picket fence inking have become bold and the rails more consistently applied. Mort would sometimes also use standard crosshatching, as seen on our far left and on the lower part of the woman’s dress. When doing so, he would frequently place the crossing lines at an acute angle so that the white spaces are elongated.

Young Romance #29 (January 1951) “Diagnosis: Love” page 5 panel 3, pencils and inks by Mort Meskin

The above panel provides a better example of Meskin’s penchant for outlining shadows. That the boldly brushed dark spot on the center man’s jacket is a shadow can be seen by the presence of the profile of a nose. Mort would occasionally have a dark shadow trace a path down one side of a figure, such as the man on our left.

Justice Traps the Guilty #56 (November 1953) “G-Man Payoff” page 5 panel 6, pencils and inks by Mort Meskin

When artists both draw and ink their own work the two art stages will sometimes reinforce one another. That is what I believe happened with the eyebrows that Mort gave his men. These eyebrows are inked with a method similar to how Meskin handled clothing folds, two or three narrow overlapping brush strokes would trace the path of the eyebrow. This resulted in eyebrows that were wide, simple and made somewhat angular turns. As we will see below, Mort became so entrenched in inking eyebrows this way that it could affected how he inked Kirby’s pencils.

The above panel also shows how Meskin would sometimes fill in part of a blank background with crosshatching. As is generally the case, here his lines meet at an acute angle, not at right angles some other inkers prefer.

Young Romance #30 (February 1951) “My Lord and Master” page 3 panel 1, pencils and inks by Mort Meskin

Sometimes Mort will use his brushwork to create a side of a figure that is both a narrow shadow and a wide outline. This does not show up often, but is very distinctive when it does. I am sure further study of Meskin’s abundant output will show other inking techniques that while not common can be useful in determining attributions.

Young Love #68 (December 1955), pencils and inks by Mort Meskin

Covers are important for the sale of a comic and the higher quality paper allows a superior printing. Therefore artists take more care in the creating artwork for covers. However the S&K studio artists usually did not get a chance to provide cover art, Jack Kirby would do all cover art when a photograph was not used. But when Simon and Kirby launched their own publication company, Mainline, Jack was so busy that for a year the covers for the Prize romance titles would be done by other artists, including Mort Meskin. On none of his romance covers would Mort use picket fence patterns or any of the other traits of S&K Studio style inking. For the spotting on Young Love #68 Mort relied mostly on his use of narrow brush strokes. Note how on YL #68 the back of the man’s jacket and pants has that narrow shadow or wide outline that we saw before.

Mort Meskin was such a prolific artist that the possibility of the use of assistants has to be considered. In preparation for writing this post I reviewed a lot of Mort’s work from 1950 to 1956, there is so much work that I did not have the time to review it all. This review confirmed my previous conviction, Mort had little if any assistance in inking his art. Almost all the spotting looked like it was done by the same hand.

Some of Meskin’s inking techniques are not limited to him alone. The use of narrow, often overlapping brush strokes can also be found in stories by George Roussos as well. This is not too surprising since Mort and George worked together in the late 40’s. The narrow brush strokes were not the only think George picked up from Mort, a lot of his penciling was clearly influenced by Meskin as well. Nonetheless Roussos did not adopt all Mort’s inking techniques so the two can be distinguished. However a discussion about Roussos will have to await another post. I will say that I have yet to find an example of Roussos inking Kirby (that is until the Silver Age).

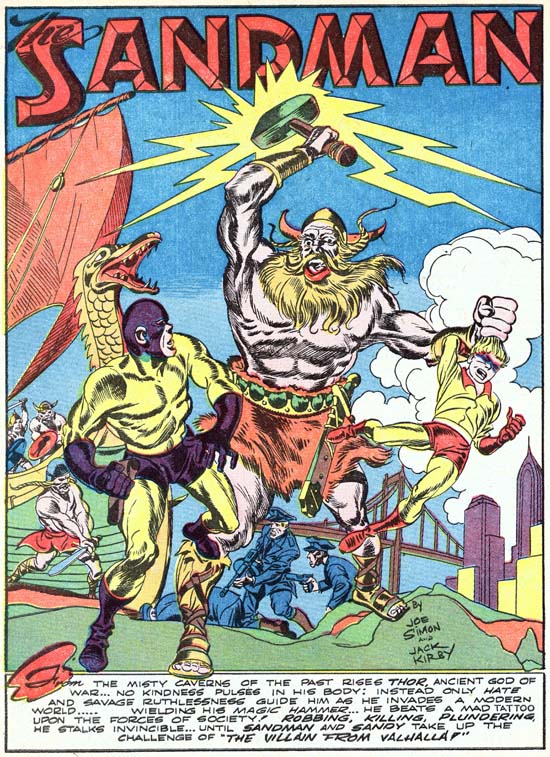

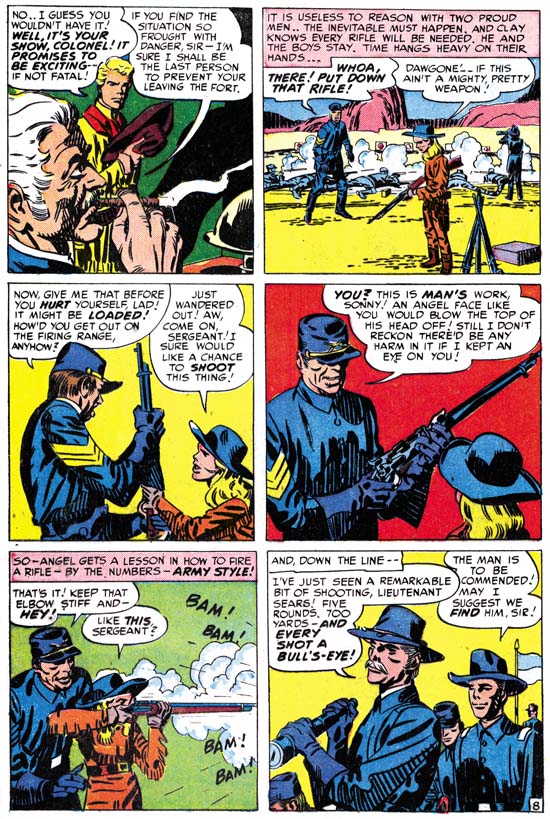

Boys’ Ranch #4 (April 1951) “The Bugle Blows at Bloody Knife” page 8, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Mort Meskin

The Jack Kirby Checklist attributes most of the inking in the classic Boys’ Ranch to Joe Simon. Actually it is not hard to recognize Mort Meskin’s inking in much, if not most, of it, particularly after the first couple of issues. The biggest difficulty I faced with choosing an example of Mort inking Kirby from Boys’ Ranch was that I believe Mort was the penciler for at least some of the work in that title that has generally been credited to Jack. But the drawing in “The Bugle Blows at Bloody Knife” looks so much like Kirby’s that I am confident that he was the penciler. I am equally as confident that Meskin did the inking. Note the narrow clothing folds in panels 3, 4, 5 and 6. See how the shadows have a strong outline, most obvious in panel 4, but can even be found on the officer’s forehead in panel 1. The back of the soldier in panel 3 could be described as either a narrow shadow or wide outline. The eyebrows in panel 1 and 6 are simple with angular turns. All of these are typical Meskin traits.

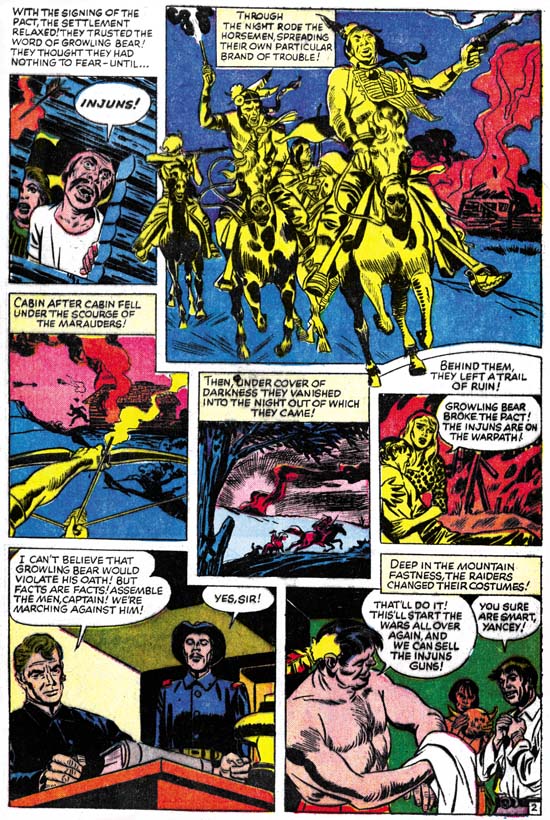

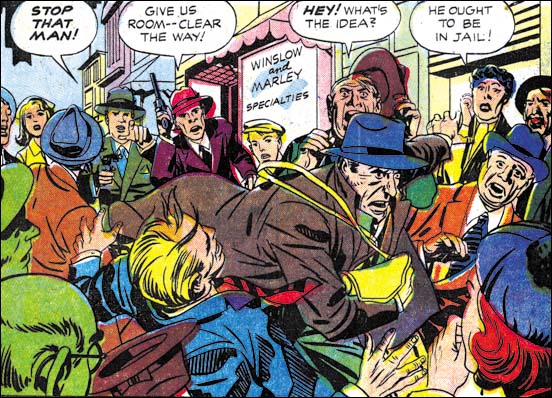

Police Trap #6 (September 1955) “Only the Guilty Run”, page 1, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Mort Meskin

The two gun carrying detectives in the background are so typical of Jack Kirby that he must have been the penciler. At a glance the inking appears typical S&K Studio style. But note how the clothing folds are long and narrow. The final giveaway is the thief’s eyebrows are simple with angular turns. There is little doubt that this is another example of Meskin inking Kirby.

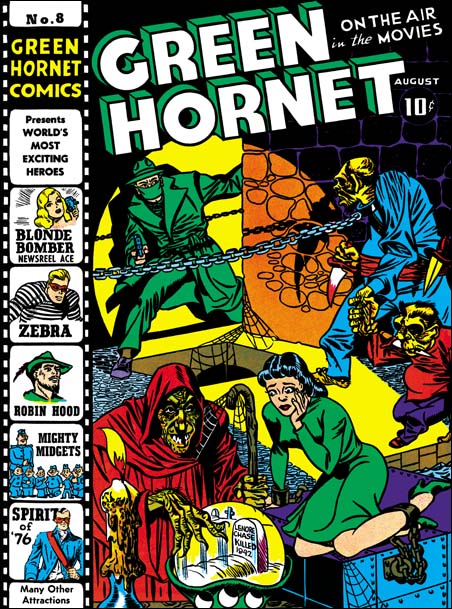

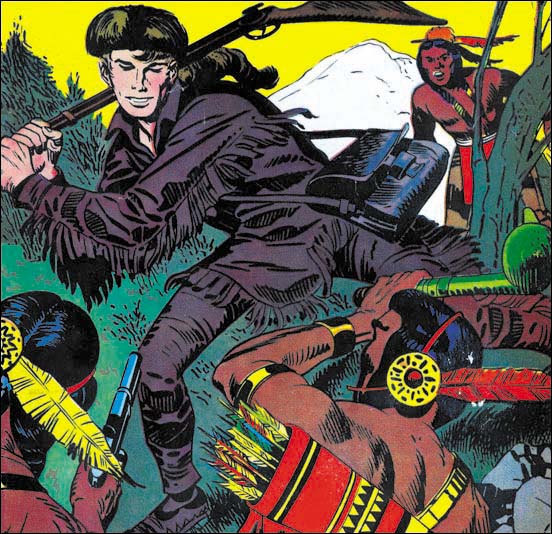

Western Tales #32 (March 1956), pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Mort Meskin

My final image is the cover of Western Tales #32. This work was not included in the Jack Kirby Checklist. The last time I posted on it I attributed both the pencils and inks to Joe Simon. The fact that it was not Kirby’s inking and the stiffness of the Indians (especially the one in the right foreground) suggested to me that Joe might be responsible. After all Simon has shown himself to be excellent at mimicking Kirby. However Crockett’s pose seems more dynamic then what Joe has ever done without using swipes, and it was just the sort of thing that Jack was so good at. Perhaps the awkward pose of the Indian on the right was due to the limited area left over from Davy’s figure. As for the inking it simply is not Kirby’s work. Note the long and narrow clothing folds, Davy’s angular eyebrows, and the way his back is outlined by a narrow shadow. None of these are Kirby traits but all are characteristic of Mort Meskin’s inking. This magnificently inked cover shows that Mort had complete mastery of the S&K Studio style. Mort’s brushwork has the same sort of bold confidence that Jack and Joe also possessed. Although it may not be a reliable enough trait to rely on in determining attributions, Meskin’s brush does seem a little more mechanical then either Simon’s or Kirby’s.

A few months after Western Tales #32 Meskin would stop providing work to Simon and Kirby. If the GCD is correct, Mort had actually returned to working for DC a couple of years earlier. Now having left S&K, DC would become Mort’s main source of income until he abandoned the comic book industry. Meskin’s final DC period overlaps Jack Kirby’s time there, however none of Kirby’s DC work that I have seen was inked by Mort.

I have not made a thorough examination of Jack Kirby’s work for the purpose of determining what ones were inked by Mort Meskin. I want to hold off on that effort until I review some more S&K artist/inkers. So far the only other one I have posted on was Marvin Stein.