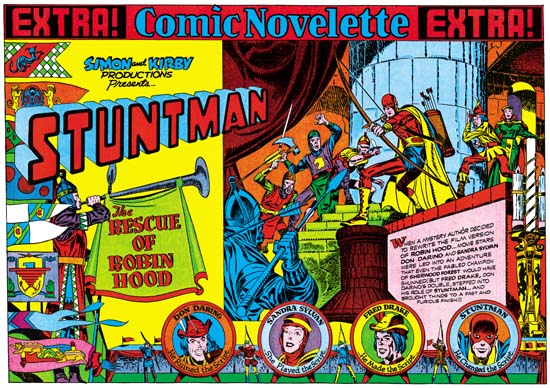

Comicscope Advertisement on the back of Wonderworld #13 (May 1940)

Not a toy, but a real projector! Show your own films at home – charge admission. Now for the first time you can use comic strips in the Comicscope and screen them in any size and in full color.

In the above ad, the Comicscope was used to promote Fox comics. Sending in the coupons from 5 Fox comics, along with 15 cents and 3 cents in stamps would get you this marvelous invention. Add it up and the total cost would be 68 cents, and that includes being able to read the comics. Later the Comicscope would be sold for 25 cents plus 3 cents in stamps. How could anyone possible sell a real projector for 28 cents? Sure this was back in the early 40’s and 28 cents was worth a lot more. But comic books were printed on the cheapest paper using the crudest printing process and they could be bought for 10 cents.

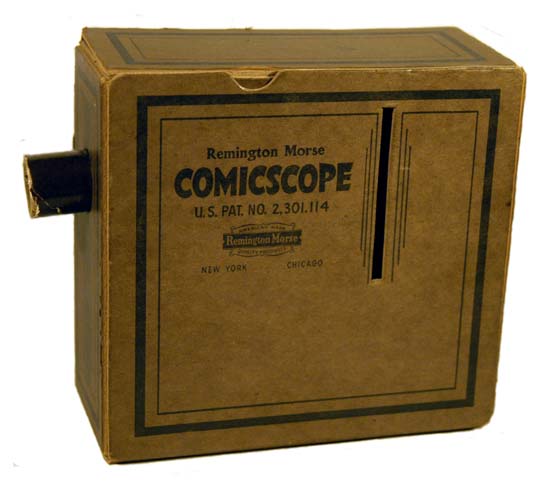

Comicscope

Well if nothing else Comicscope is a marvel in cost saving design. It is little more then a cardboard box, a cardboard tube and a cheap simple lens. There is a hole in the bottom so that a light can be used but I suspect that the light was not actually supplied. The Comicscope had slots on the side through which a comic strip could be inserted. The slot is a little under 3.25 inches high, just enough room for one panel row from a comic book. Forget about splashes or covers. The “screen them in any size” of the ad refers to the projected image, not the source material. Even the size of the projection is misleading. The projected image is not very bright, the Comicscope could only be used in a very dark room. The image size is adjusted by the distance of the Comicscope from the “screen”. The lens tube is moved in or out to achieve proper focus. However the larger the projected image the lower the relative brightness. No matter how dark the room, light leakage from the Comicscope itself would make larger projections difficult to see. To make it even worse, the device reverses the image. In order to get the correct vertical orientation you have to slide the comic strip in upside down. But that fixes what side is up, but not what is left or right. All text comes out backwards. But you would have a hard time reading text anyway. Only a circular image is projected and that covers only part of a standard size comic book panel.

I doubt that anyone would get away with selling such a product today, despite the cheap cost. I say that not only because of the poor quality of the final projection but because of the safety hazard. It would seem to me that putting a light bulb in a closely confining cardboard box is a receipt for a fire. The material is rather denser then typical cardboard but I have got to believe it is still flammable.

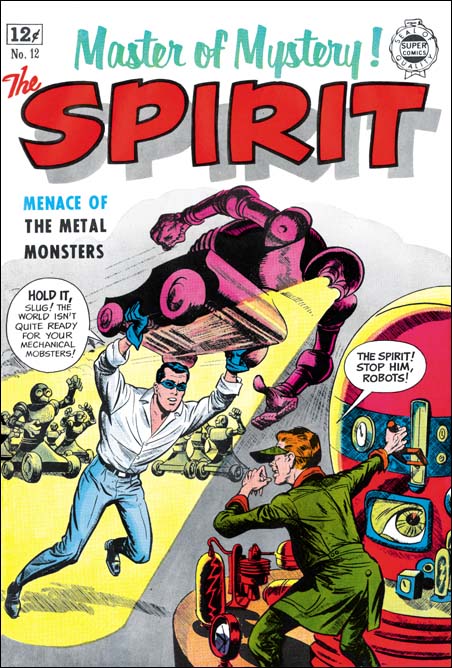

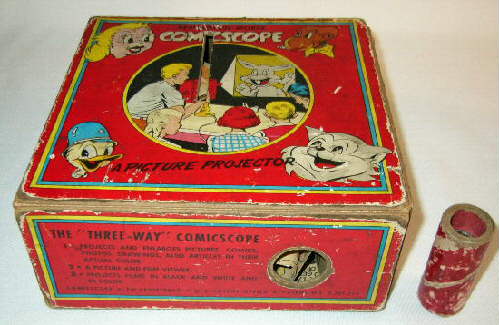

Comicscope with cartoon characters

Comicscopes seem to come up for sale from time to time. Most that I have seen are plain like the the first photograph I provided. But there are some with printed cartoon characters on the side. They are all cartoon type and funny animals. None are superheroes like shown in the advertisements from the early 40’s.

So who made this wonder? Well the box has on it Remington Morse (“American Made, Quality Products”). It provides no address but says New York and Chicago. The flap provides the further information that Remington Morse was a division of Hamilton Ross Industries. A quick google search for Remington Morse does not provide much. There was a Remington Morse in Chicago that made some 78 records. As for Hamilton Ross Industries I have come across references to toy sewing machines and a real electric hand grinder.

The original ad states that the Comicscope has been registered and is patent pending. The earliest ad I have seen is May 1940, but that may not mean much since I have limited access to early Fox Comics. I have seen an August 1939 issue of Wonderworld #4 which does not advertise Comicscope. We will see below that the date of the introductory of the Comicscope is important so I would greatly appreciate it if anyone could tell me about the appearance, or lack thereof, of Comicscope in Fox Comics before May 1940. The Comicscope I first illustrated does have a patent, No. 2,301,114. Through the marvels of the Internet you can actually see this patent.

But the image provided is somewhat small so you may need a large monitor to read it. The patent was filed March 20, 1940 and actually issued on November 3, 1942. Comic cover dates are advanced two months so the ad I showed above came out about the same time as the patent filing. So it may in fact be the earliest ad for Comicscope. The patent says that Victor S. Fox (New York) and Robert W. Farrell (Bronx) are the assignors and “by mesne assignments, to said Farrell”. Don’t you just love lawyerese? Such an elegantly incomprehensible language! I think what they are saying is that Fox and Farrell took out the patent but that Farrell was going to be the one that actually used the patent and have it manufactured.

Victor S. Fox was from England and previously had been a stockbroker. He was indicted for mail fraud and related activities on November 27, 1929. The outcome of this is not known. In a story that is now a legend, Fox was an accountant for the company that became DC Comics. Seeing how well Action Comics was doing, Victor launched his own company which, with his usual immodesty, he named Fox Comics. Gerard Jones in “Men of Tomorrow” says that this legend is actually false. After all these years who can say one way or the other what is legend or history? We can say say with more confidence that Victor went to Eisner & Iger studio and asked them to create another Superman. They developed Wonderman and DC Comics quickly sued. Eisner & Iger refused to take the blame so Fox started his own bullpen and hired Joe Simon as editor. Joe only stayed about three months before moving on to Timely. A move that Joe says was not taken kindly by Fox. I previously posted on the connection of Comicscope to the early copying of Captain Freedom from Captain America. The use of Captain America in an ad for the Comicscope was surely meant to be parting shot at Joe by Fox and Farrell. With Captain America’s great success, Timely probably would not allow Cap’s continued use in these ads.

Less is known about Robert Farrell. Joe Simon has described him as Victor Fox’s right hand man. Bob ran the operation when Victor was out of the office. According to Joe in his book “The Comic Book Makers” the Comicscope was Bob Farrell’s product but never made a profit. However an Comicscope ad from 1942 declares that 63,458 had been sold. That is a lot of Comicscopes to have been sold without a profit, and I believe they continued to be sold into the 50’s. Surely the makers of such a fine product would not exaggerate about the sales!

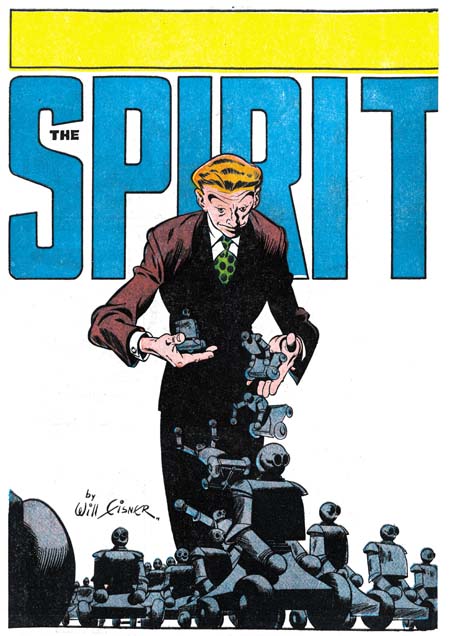

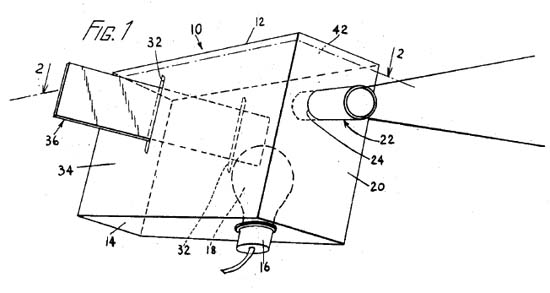

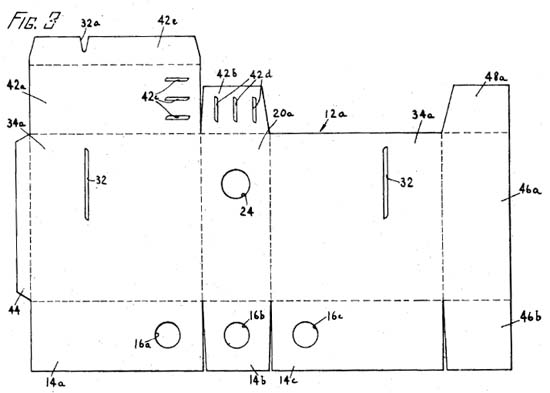

Comicscope 3D diagram from the patent.

The patent for Comicscope includes the above diagram. The electric bulb provides the light for the comic strip which the lens projects. The reason for the low light level of the projected image is that the light source shines onto, not through, the source image. The hole in the bottom of the box for the light is just big enough for the neck of a standard bulb. Further the box is just wide enough for the that bulb. The bulb had to be screwed into the socket from within the box.

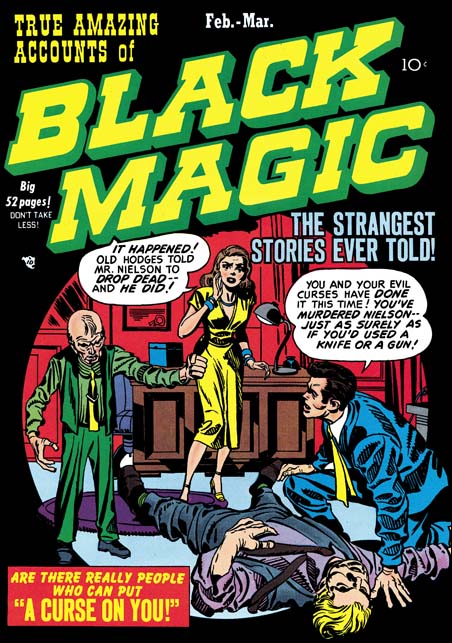

Comicscope plane view (before folding) from the patent

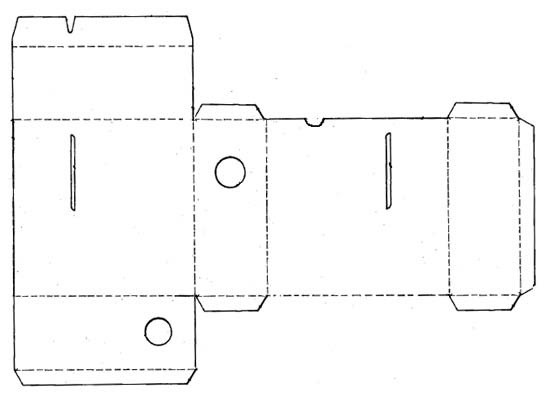

The patent statement starts off describing the construction of the box from a single flat blank of cardboard or sheet metal. Actually I believe the use of sheet metal would be unrealistic as the metal would become too hot from the lamp. The patent says the box would be easily constructed, “can be readily assembled by children”. However it appears the Comicscope was always sold assembled and never flat.

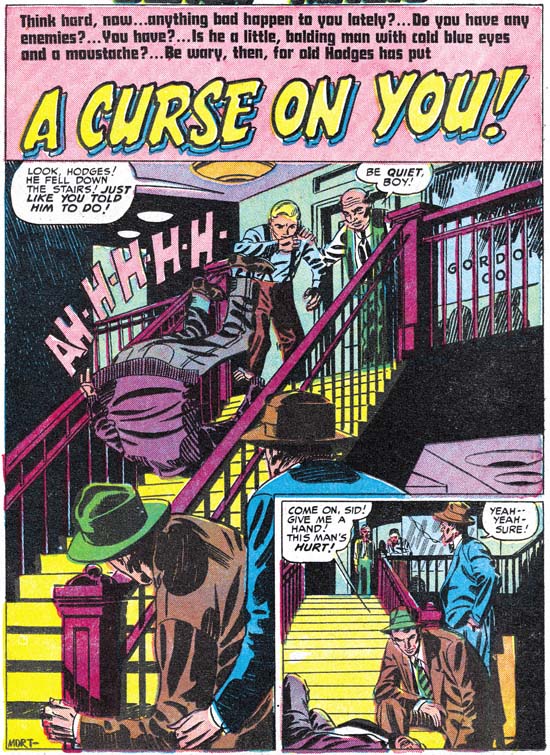

Comicscope plane view (before folding) as actually manufactured by Remington Morse.

The original patent shows some unusual features. In the figure 42c and 42d denote slots cut into the top. When the box was folded up the set of slots from the two flaps were meant to line up to provide a way for heat to be exhausted. But actually it would be hard to keep the manufacturing of the box accurate enough to line up the slots properly in order to accomplish their purpose. Even if they did succeed to align, the slots would not only let out heat but also light from the bulb immediately below. Because the projected image is so dim, this light leakage would be very undesirable. These slots were eliminated in all the Comicscopes that I have seen. A similar problem appears for the holes 16a, 16b and 16c. After folding these holes are meant to line up well enough for inserting the neck of the light bulb. But such alignment of three parts seems unlikely and in the final product two of the flaps are greatly shortened so only a single hole is use.

The lens assembly is made by placing the lens into a cardboard tube. Two further cardboard tubes are just smaller then the first so as to fit very snuggly inside. These two smaller tubes are inserted from both sides thereby holding the lens in place.

Halfway through the second page of the design there is the statement: “Having thus describe our invention, what we claim and desire to secure by Letters Patent is:”. Five detailed paragraphs follow that seem to repeat the same statement in slightly different forms. I am not a lawyer but I suspect they wanted to insure that it was not just the exact design they wanted patented. Remember that the actually manufactured Comicscope did not follow the patent exactly. What seemed more important to Fox and Farrell was having an optical projector that used an opaque image lighted by a light bulb. That there would be slots in the side for inserting and moving the source image. They seemed concerned about protecting the use of the device.

Junior’s Television

Above is an image of device that seems much rarer then the Comicscope. But when you look at the top box and the lens assembly there can be no doubt that there is a close relationship between Junior’s Television and the Comicscope. Mike Schultz provides a webpage on Junior’s Television. On the box there is an address which does not include a postal zone code and to Mike suggests a date before 1943. Postal zone codes were used in the US between 1943 and 1963 after which zip codes were used. Mike further goes on to guess that a date of about 1939-40 “to capitalize on the publicity that TV generated at the New York’s World Fair”. But with the lack of firm evidence all that can be said for certain is that it appears two practically identical devices both came out in the early 40’s.

There is a web page in Tomorrow’s Heroes that shows a comic book ad for Junior’s Television. The image is a bit fuzzy by it includes two addresses. One seems to be the same address as on Mike Shultz’s box, only this time using a different name (Enterprises Unlimited) and with the postal zone code. Besides the box and stand of the image above the ad says it comes with a carrying case, a television screen, an electric cord and a light socket. Much more then it would seem is provided by Comicscope, but for a heftier price tag of $2.98. Again it is fuzzy, but the ad appears to indicate that the patent is pending while the box itself only says trade marked. The trade mark protects on the name Junior’s Television and not the device. If Enterprises Unlimited had approval to use Fox and Farrell’s patent it would say so.

So we have Comicscope and Junior’s Television coming out at about the same time. Obviously one is copying the other. I doubt very much that either Fox or Farrell actually did the Comicscope design themselves. But that does not mean they copied Junior’s Television. They could have come up with the idea and had one of their artists draw up the plans. I have got to say that Junior’s TV seems like a well thought out assembly while Comicscope is just the essential box and lens. But we need better dating for both devices before we can guess who stole from who.