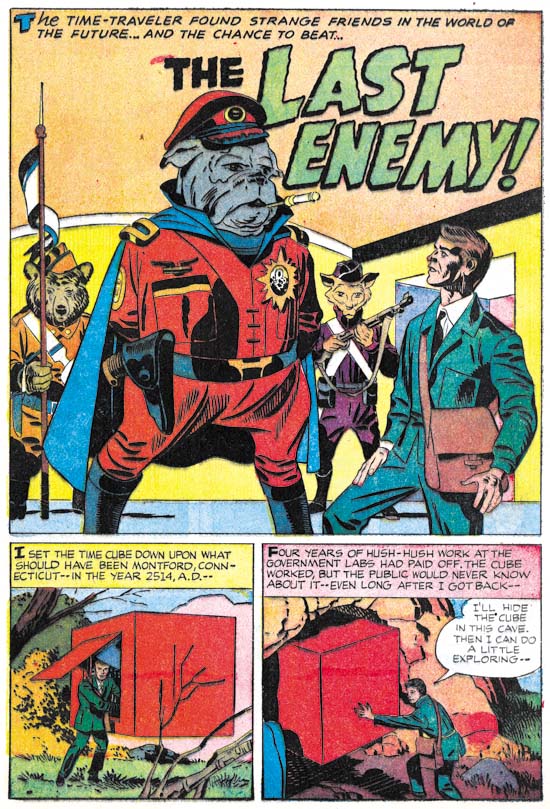

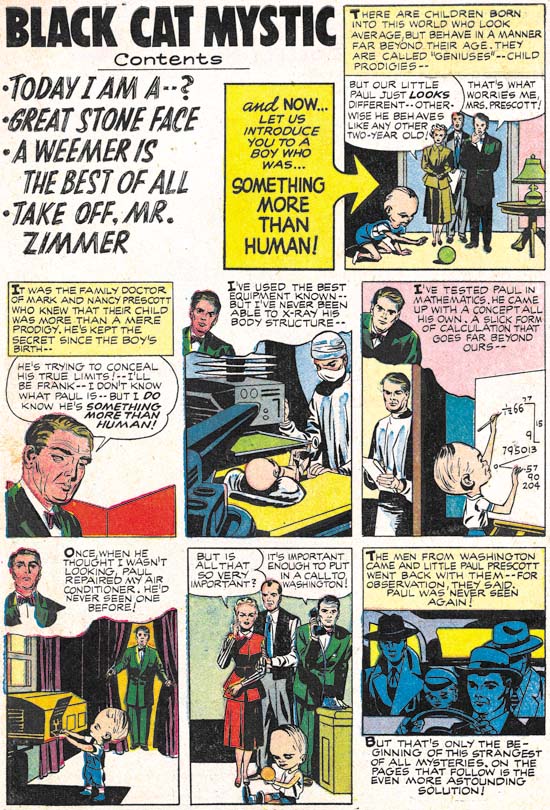

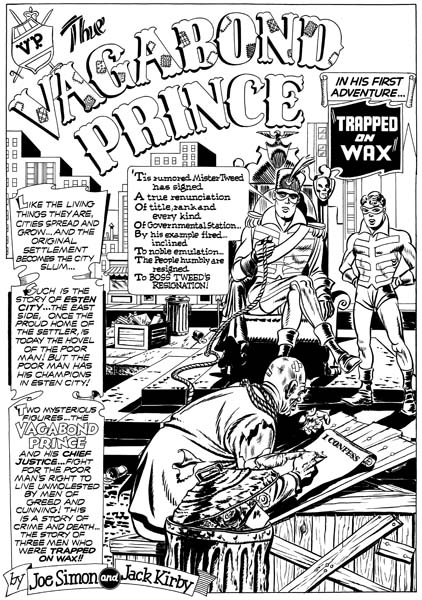

Some years ago I wrote a serial post called the Wide Angle Scream where I discussed the various Simon and Kirby double page splashes that were published over the years. I did include one Stuntman double page splash that had not been published (Terror Island) but there were two others that I did not discuss. Actually it is a not quite accurate to say these wide splashes had not been published as they were included in Joe and Jim Simon’s “Comic Book Makers” (colored, I believe, by Greg Theakston) and more recently in “The Simon and Kirby Library: Superheroes” (colored by yours truly). At the time I did not have scans of the original art and “Terror Island” was the only spread that I had a reduced size copy of. Now I would like to return to these unpublished Stuntman splashes as a crossover with my serial post Speaking of Art.

Stuntman Comics #3 (intended) “Terror Island”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Enlarged view

As mentioned above, I had discussed the splash for “Terror Island” previous but a few comments about the original art seem appropriate. This splash is missing a heading at the top of the page. One probably was present as there appear to be stains left by rubber cement. The Stuntman logo is a recent addition as the original also fell off. But most noticeable about the original art is the damage found along the margins of the illustration board. In Joe Simon’s autobiography “My Life In Comics” he writes:

The spreads had been kept in the attic where they suffered decay at the hands of the weather and damage at the paws (and teeth) of marauding squirrels.

While I am sure that this original art, and the splashes for “Jungle Lord” and “The Evil Sons of M. LeBlanc” spent some period in an attic, I doubt that the damage that they show was due to squirrels as I found no sign of marks from teeth or claws. Rather I believe that the heated conditions frequently found in attics has left the illustration boards brittle. Comic book collectors are familiar with the brittle pages sometimes found in golden age comics caused by the presence of acid in the newsprint paper. The illustration boards that Simon and Kirby used probably did not have as much acid as found in comic book newsprint but there seems to be enough that these art boards typically yellow with age. In the case of the Stuntman original art the heat has accelerated the detrimental effect of the acid making the boards brittle. Most of the damage occurs at the corners which would be expected since that is where the boards are most likely to hit up against more unforgiving objects. The boards are not actively crumbling but must be handled with care.

I should also mention the Stuntman Comics issue number I have assigned these pieces to. Simon and Kirby only used double page splashes in the centerfold of the comics. That way there would be no problems aligning pages properly with the rather primitive publishing methods used for comic books of the day. Only two issues of Stuntman ever reached the newsstands. A third issue was mailed to subscribers but it was much reduced in size and contents. Most importantly the third issue did not use a wide splash. The three unpublished Stuntman wide splashes would have appeared in Stuntman Comics issues #3, #4 and #5 if not for the unfortunate sudden cancellation of the title. I have assigned the different splashes to the intended issues based on completeness of the art. The splashes for “Terror Island” and “Jungle Lord” were both completed. However on “Terror Island” has story art at least some of which was completely inked while the story art for “Jungle Lord” on received outline inking without any spotting. As we will see the inking of the splash for “The Evil Sons of M. LeBlanc” was never finished and therefore it was worked on last.

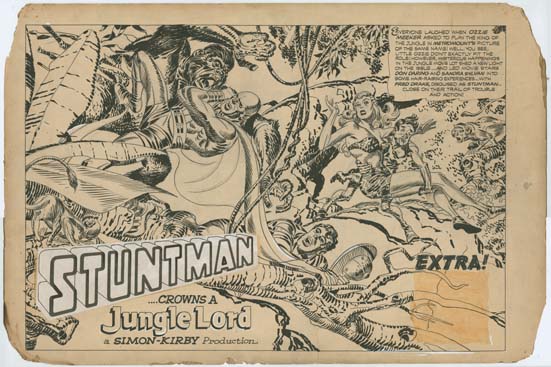

Stuntman Comics #4 (intended) “Jungle Lord”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Enlarged view

Like “Terror Island” the inking of “Jungle Lord” appears to have been completed. Only a small area in the lower right corner seems to have only received outline inking. The board is stained in this area so it seems that originally a square piece of paper or stat covered the area until it was lost when the rubber cement failed. The Stuntman logo is a new addition to replace the original which also seems to have become detached.

Previous Stuntman double page splashes had been visually complex but in “Jungle Lord” Simon and Kirby have distilled it to the essentials. Or as essential as could be expected with five main characters. A dramatic fight scene between Stuntman and a gorilla is balanced with a humorous scene of a skinny individual in a Tarzan suite carrying off a similarly clad Sandra Sylvan while below the ironically named Don Daring bridges the two. While visually complex would be done in the future (“Social Night in Town” and “Remember the Alamo”) simpler designs like this one would dominate.

Stuntman Comics #4 (intended) “Jungle Lord” close-up, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

All the unpublished Stuntman double page splashes had terrific inking, not surprising since Jack was doing his own spotting. But in my opinion “Jungle Lord” has the best inking of the three. Jack used his blunt brush in a free but controlled manner that is just marvelous to behold.

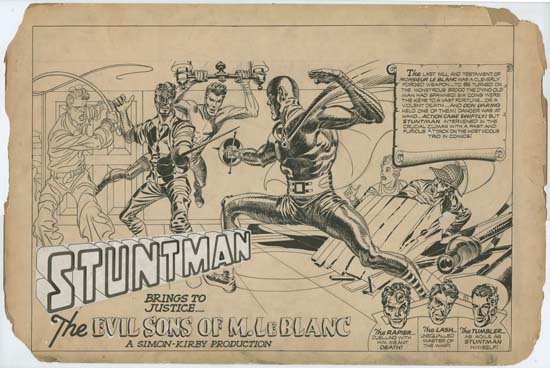

Stuntman Comics #5 (intended) “The Evil Sons of M. LeBlanc”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Enlarged View

Clearly Kirby was working on “The Evil Sons of M. LeBlanc” when Simon and Kirby received the news that Stuntman had been cancelled. Three of the figures appear to be fully inked, one (the Tumbler) may be almost but not quite completed (mainly work is lacking on his left forearm) and two only have outline inking. Stuntman figures large, probably the largest figure in a splash that Kirby ever drew during the period he partnered with Simon.

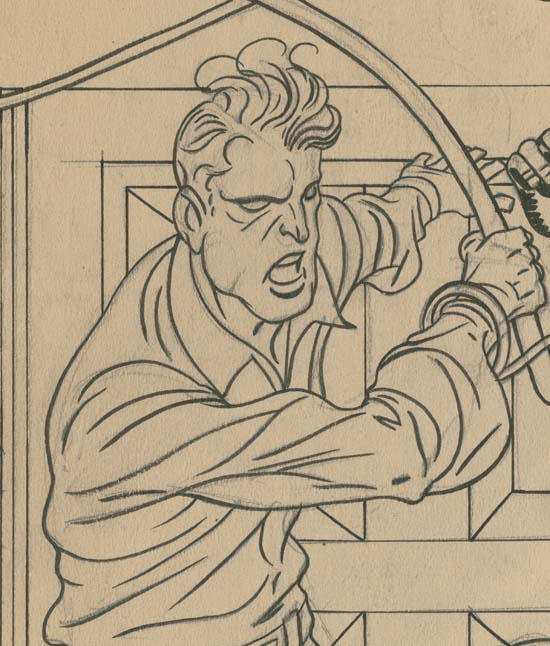

Stuntman Comics #5 (intended) “The Evil Sons of M. LeBlanc” close-up of Lash, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Standard inking procedure for Simon and Kirby was to first provide simple line inking. Because Kirby’s pencils were pretty tight this task could be assigned to a less talented artist. It is interesting to compare the lined inked Lash with an unfinished Boys Explorer page that did not progress beyond the line inking (Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking). The lines found in the Boys Explorer page show little variation in width almost as if they were made from wire. On the other hand the lines used to construct Lash show variation in thickness line as compared to line and also along the length of a line. The difference is not great but it does suggest a more talented hand did the line inking for the Stuntman #5 splash. Although it is hard to be certain, but I believe that on this splash Jack did the line inking himself.

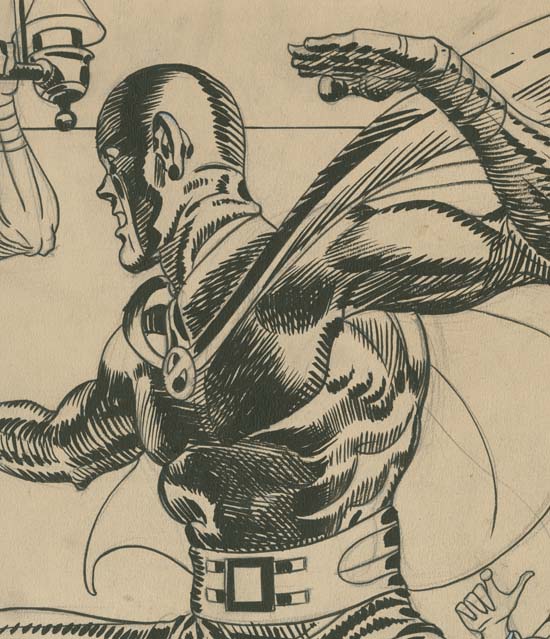

Stuntman Comics #5 (intended) “The Evil Sons of M. LeBlanc” close-up of Stuntman, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

The figure of Stuntman is almost certainly complete, it is hard to imagine how anymore spotting could be applied without having a detrimental effect. While the spotting does not have quite the bravura brushwork as found in the “Jungle Lord” splash it can still take the breath away.