Joe Simon’s first comic book art was published in January 1940 (cover dates for Keen Detective #17, Daring Mystery #1, and Silver Streak #2). Yet just five months later he was already an editor for Fox Comics. On the face of it this was a rather dramatic rise in his career. Joe was (and still is) a talented artist but during those early days of the comic book industry there were other even more talented artists who never got further then the drawing board.

Some have attributed Joe’s success to having come from a more privilege background. Joe’s family did not live in one of the boroughs of New York City but that does not mean they were well off. Most of the time the family lived in Rochester where Joe’s father, Harry, struggled to support the family. Harry was a tailor by trade but his attempts at union organizing made finding jobs difficult. At one point the family moved to Chicago into a particularly rough neighborhood. Joe tells how at age ten he was in a fight almost every day as other boys tried to take from him what little he had. (Afterwards Harry would examine Joe’s knuckles to verify that he had given a good account of himself.) No there is nothing in Joe Simon’s background to suggest he had some advantage over his contemporaries.

Others have suggested that Joe’s college education was the reason for his quick career rise. One of the originators of this idea was, of all people, Jack Kirby. Jack should have known better. Joe did not attend any college and never received a degree.

Of course it was not just luck that Simon became an editor. Joe was obviously ambitious and a self promoter. One evidence of this can be seen in how Joe made sure to include his signature on much of his early art. Joe was not alone in being ambitious, other artists were as well. Will Eisner started as an artist before quickly seeing an opportunity of starting studio with Jerry Iger. Al Harvey started as an artist before becoming a publisher. But not all artists were so quick to try new opportunities. Perhaps if he had started earlier or had more money, Joe also would have tried setting up a studio but he did apply for the Fox editor position instead. Although not all artists were ambitious as Joe, there must have been some others who applied for the Fox editorial job. The other artist would likely have more experience in the comic book industry then Joe’s 5 short months. How did Joe manage to get the job?

Actually the experience of most, if not all, of Joe’s possible job competitors did not amount to much. It really amounted to having spent more time drawing comic books. Being a good artist, however, really was not a necessary feature of an editor. There were other tasks that an editor would need to do such as providing layouts, putting together an entire book, or interfacing with the printer or publisher. Joe had an edge up on other applicants in some of these other tasks. Previous to entering the comic book industry, Simon spent about seven years as a newspaper staff artist. “Meanwhile”, the Milton Caniff biography by Robert C. Harvey, provides a wonderful examination of his experiences as a staff artist and I am sure Joe’s was not that much different. Yes the job consisted in providing illustrations and such for the paper, but it also doing meant doing layouts, creating decorative embellishments (dingbats) and other similar choirs. It was the experience as a staff artist for a period of seven years that Joe could use to promote himself as a good candidate for the editorial position.

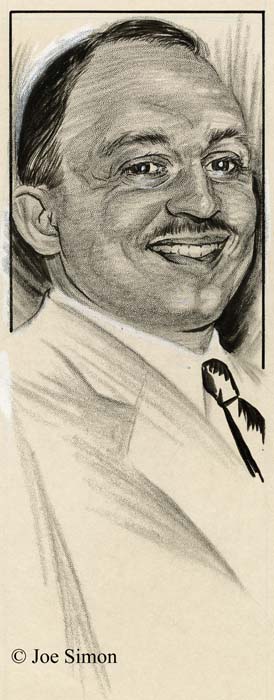

My thinking about Joe’s time as a staff artist was brought on by recent work that I have been doing on inventorying Joe’s personal collection. I have previously discussed some of Simon’s newspaper work. Work like sport and fiction illustrations, and political commentary cartoons. Recently I have scanned another aspect of his newspaper career, political portraits. There are 21 portraits all done on stipple board in crayon, ink and white out. Most of them are stamped on the back at the time of delivery. Unfortunately this stamp includes the day but not the year; the dates range from October 1 to 23. Some have names on the front and through the wonders of Google and the Internet I have found some of the names on a site called The Political Graveyard. Those that I have been able to identify are all politicians from Monroe County, New York. It is there fore likely that this was done while Joe was working for the Rochester Journal which according to his book, “The Comic Book Makers”, was from 1932 to 1934.

The above portrait was of Acton Langslow who, according to The Political Graveyard, was a Democrat, Candidate for New York state assembly from Monroe County 1st District in 1935. The two I selected for this post were both Democrats, but there were some Republicans as well.

Another has the name D’Amanda, which based on The Political Graveyard, was Francis J. D’Amanda a Democrat. Candidate for New York state assembly from Monroe County 3rd District, 1928, 1932; candidate for New York state attorney general, 1950; delegate to Democratic National Convention from New York, 1952 (alternate), 1956.

The manner of execution is quite interesting. The crayon (by this term I am referring to artist crayon, not those used by children) is used in a very loose manner with distinctive individual marks by the crayon. The hair and ties are done in ink using a brush with the ties being particularly rough. Yet when the original art is shrunk down in size, as it would have been for publication, the rough mannerisms disappear into an almost photographic representation. It was quite a performance by an artist who, if my dates are correct, was just out of high school.