I have previously posted on some of the artists that have inked Jack Kirby’s pencils (Mort Meskin, Marvin Stein and Captain 3D). Unfortunately my restoration work for Titan’s Simon and Kirby Library takes up so much of my time that I have been unable to pursue this topic further. However my work for the upcoming Science Fiction volume has allowed me to examine in detail the inking used for Race for the Moon and Blast-Off. It was particularly fortunate that I had available either the original art or flats (production proofs of the line art) of pretty much all the interior art for these two titles*.

Before discussing the evidence from the art, it would be best to start with a presentation of some of what has been said by others. In his book, Joe Simon, My Life in Comics Joe writes about Race For The Moon:

When I proposed the title, Jack welcomed the work. I wrote most of the stories, although Dick Wood, Dave Wood and Eddie Herron contributed some scripts. Because Kirby was penciling some of them, I was able to sign up three of the best inkers in the business. Reed Crandall, Angelo Torres, and Al Williamson, each of them a brilliant artist in his own right, all wanted to work with Jack. In addition to inking Jack’s pencils, they got to illustrate some stories on their own.

In an interview with Al Williamson from the Jack Kirby Collector #15:

TJKC: Did you and Wally ever discuss how to approach inking Kirby?

AL: No, it was a job. I remember going up to Harvey and getting work there. They said, “We haven’t got any work for you, but we have some stories here that Jack penciled. Do you want to ink them?” I’d never really inked anybody else before, but I said, “Sure,” because I looked at the stuff, and thought, “I can follow this.” It’s all there. I inked it, and they liked it, and they gave me three or four stories to do.

TJKC: I was just reading some of those Race For The Moons. There’s some beautiful stuff there.

AL: Well, he did a beautiful job. Some of it was redrawn by somebody there, I guess because it didn’t pass the Comics Code or something. There’s parts that I didn’t ink, because it’s not my drawing or Jack’s drawing. Somebody went over it and changed some things, like a monster or something to make it more pleasing to the eye, which bothered the hell outta me. I never really thought I did him justice, though. The drawing is there, because it’s Jack Kirby’s drawing, but I just traced what he penciled.

TJKC: Did you feel intimidated to add too much of yourself to it?

AL: I don’t do that. If the job is penciled, I would ink it the way the guy penciled it, because it’s his pencils. If I think it needs something, I’ll call the artist up and say, “Listen, I kinda would like to add a black here. Is this all right with you?” And as a rule, they say, “Sure. No problem.” But I don’t do any redrawing on anybody’s work unless I talk to the artist-and I very seldom have to do that.

Also in the interview, Williamson remarked that he did not ink any covers. So we have Simon crediting the inking to three different artists (Crandall, Torres and Williamson) and Williamson saying he inked somewhere between three and five Kirby stories. It is important to remember that such testimonials is evidence but not the proof that all too many comic book historians take it for. I am continually surprised that so many take evidence based on memory as fact. I would have thought that from what has been learned from legal cases over the years would discredited over reliance on memory. People’s memories are not created like a video recorder saving all that a person sees and hears. Rather memories are more like stories that people create and retell over and over. Such stories are biased and often are like a morality tale that tell more about the person telling them than what actually occurred. As years pass, the memories are effectively retold and change even further. Inaccuracies are expected and not a sign that the person is lying, that is trying to deceive. So I prefer to treat such interviews as evidence but I also turn to the work itself to find further evidence to support or refute what has been said.

Alarming Tales #6 (November 1958) “King of the Ants” page 2, pencils and inks by Al Williamson (from bleached page)

Artists have their own inking techniques that they use over and over. One place to start would be to examine how an artist inks his own work. Fortunately Williamson created a story, “King of the Ants”, for Alarming Tales #6 at the same times that Race for the Moon #3 came out. Regrettably Harvey’s had very poor printing so I use a bleached page to use as an example. Page 2 illustrates a number of techniques that Williamson was fond of. One was the use of multiple very broad brush strokes that are somewhat irregular and placed side by side. Examples can be seen in the lower right corners to panels 2 and 4 in both cases right above the figure’s shoulder. As far as I can tell, these irregular inking patches are not meant to depict any realistic feature but rather serve as an abstract pattern. I do not have a good name for another technique but I sometimes describe it as mottled crosshatching. This can be found in the right side of panel 4 just above the other inking technique described above. Sometimes Williamson uses a looping ink line to describe foliage such as found in bottom center of panel 1 right in front of the fallen tree trunk. Another technique is more of an anti-inking process where Williamson removes a panel’s border such as in panel 6. I have not seen the original art for “King of the Ants” but on original art that I have seen Williamson has cut page with a razor and peeled off the panel border. Of course anyone could have done it but such borderless panels are commonly found in work that Williamson inked but not other stories done for Harvey so I attribute the action to him.

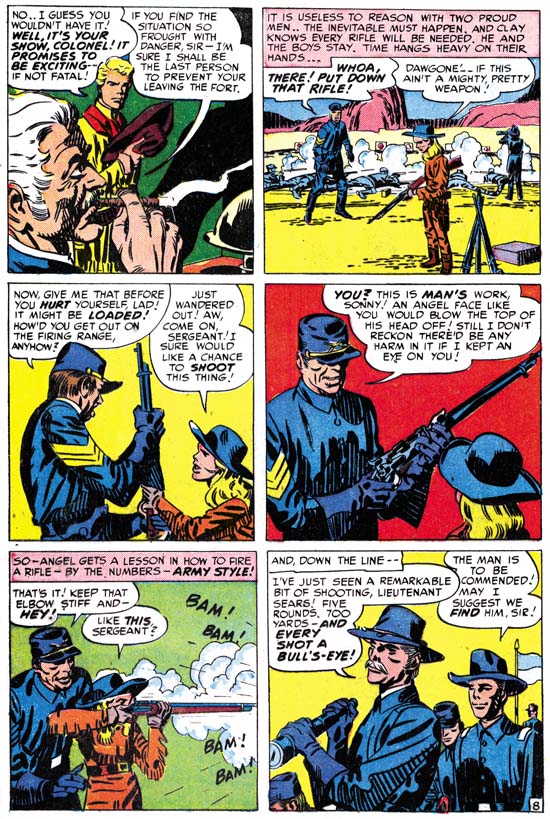

Blast-Off #1 (October 1965) “Space Court” page 5, pencils and inks by Al Williamson

It might seem odd to use work published in 1965 to illustrate Williamson’s inking techniques from 1958 but in fact the Comic Code Authority stamp on the original art was dated March 6, 1958. This date was a few weeks earlier that the approval date for the art for Race for the Moon #3 (cover dated November 1958 but Comic Code approval date of March 28, 1958). It may be a minor mystery about what title this story was originally intended or why it was not published until years later, but it is a perfect match for this discussion about inking techniques.

Some of the previously discussed techniques can be found in the “Space Court” story as well. For instance the removal of panel borders, in whole or in part. Also note the background inking for panel 5 appears to be an expansion of the technique described above. What this page shows is another technique that is not technically inking, that is the use of Ben-Day dots. These are found in panels 3 and 4 giving both a grey background. The Ben-Day patterns were applied as transparent overlay sheets that were carefully cut with a razor to cover the desired areas. Williamson used Ben-Day dots with the standard dot patters arrange in the angles used for printing but also irregular dots (mezzotint patterns) and hexagonal arrangements.

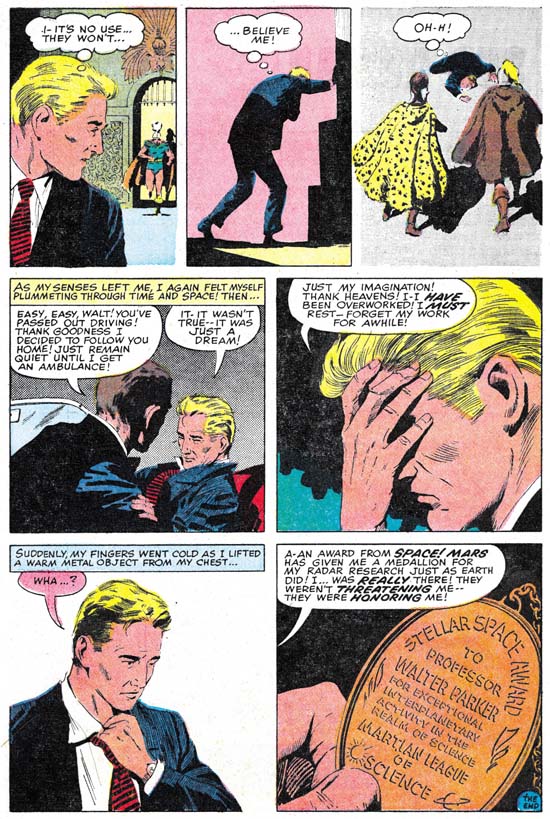

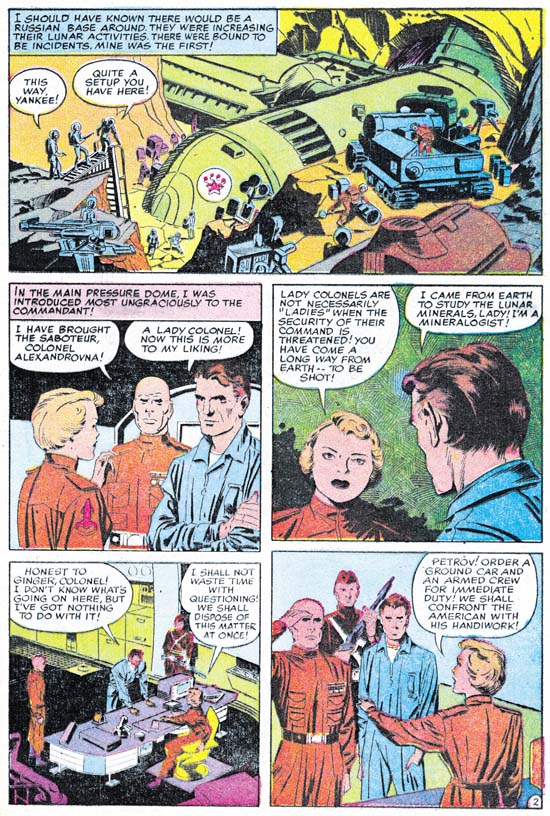

Race for the Moon #2 (September 1958) “Lunar Trap” page 2, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Al Williamson

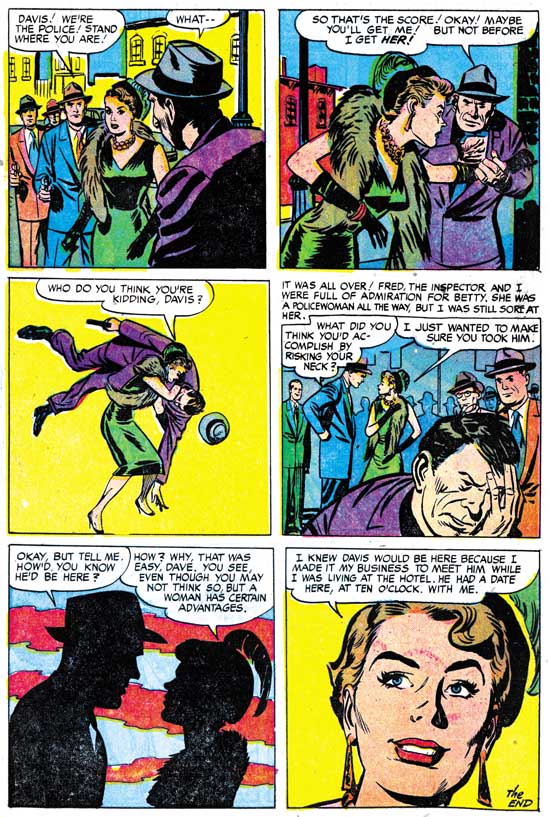

The inking of the Kirby pencils for Race for the Moon and Blast-Off can be placed in three groups that show related features. The first group consists of “The Thing on Sputnik 4” and “Lunar Trap” both from RFTM #2. These works were inked using both pen and brush. They differ from the next group is the general lack of some of the techniques that I have describe Williamson as using. None of the panel borders have been removed in these two stories and there is no use of Ben-Day dots. There is only one example of the looping ink line but this is not too surprising since Williamson often used this technique in rendering foliage and there are no plants on the moon. Two other Williamson inking techniques only appear in one panel; panel 2 from page 2 of “Lunar Trap” shown above. There we find the mottled crosshatching and that irregular broad brush strokes. Despite the infrequence or absence of some of Williamson’s inking techniques I still credit the inking to Al. As far as I can see only one hand was involved in the inking of these two stories and the pen and brush work looks very much like that found in stories I am convinced were inked by Al Williamson. I suspect these two stories were the first ones by Kirby that Williamson inked and he was just getting comfortable with working on Jack’s pencils.

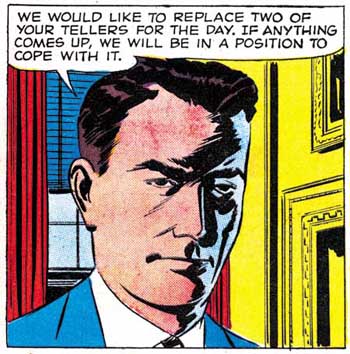

Race for the Moon #2 (September 1958) “The Face on Mars” panel 2 page 2 and panel 5 page 4, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Al Williamson

The next group of five Kirby stories are the ones that I am pretty confident in crediting the inking to Al Williamsons. These are “Island in the Sky” and “The Face on Mars” from RFTM #2, and “The Long, Long Years”, “Saucer Man”, “Space Garbage”, and “The Garden of Eden” from RFTM #3. These contain all the techniques that I describe above based on Williamson’s inking of his own pencils. I do not want to leave the impression that these techniques are abundantly found in Williamson’s inking but rather the usually can be found when enough pages are examined. I provide scans of panels from two different panels above to show some of the Williamson techniques found in these stories.

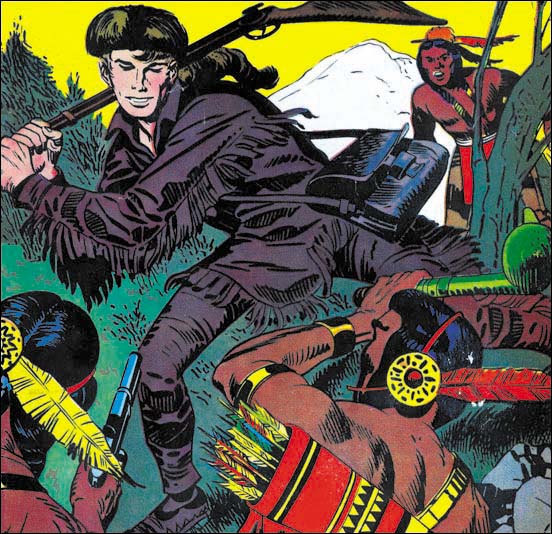

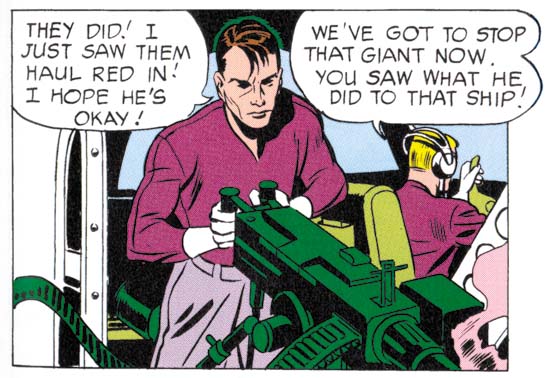

Blast-Off #1 (October 1965) “The Great Moon Mystery”, pencils by Jack Kirby and inks by Al Williamson

The third group consists of the Kirby penciled stories that appeared in “Blast-Off #1 (October 1965) which are “Lunar Goliaths” and “The Great Moon Mystery” Although I have examined the original art for these works they still are another of those minor mysteries. Neither story has Comic Code approval stamps. Further neither story has any indication of a previously intended title. Typically the original art would have on the top left just above the art the comic book title and page number it was intended for. Even when the title changed white out would typically be used to remove the outdated information so the new title and page could be added. No white out was used so the Blast-Off #1 information placed on the original art was the first applied. But both stories are Three Rocketeer stories and that feature first appeared in RFTM #3 so these two stories were likely intended for the unpublished RFTM #4. Certainly Kirby’s pencils are in the same style used for the 1958 RFTM and not at all a match for what he was doing in 1965 for Marvel Comics.

The inking of the two Blast-Off Kirby stories is more like the first, presumably earlier, group. Absent are any sign of most of the techniques I have described from Williamson’s inking of his own pencils. The only exception is the relatively frequent use of Ben-Day dots in “The Great Moon Mystery”, but they are not found at all in “Lunar Goliaths”. You can see the Ben-Day dots in the moon-scape background for the splash panel shown above. Although the comic book shows no sign of Ben-Day in the second (left) panel the original art shows that they were there. However Williamson used such a fine dot pattern that they complete got lost in Harvey’s rather crude production. Despite the fact that some of Williamson’s inking techniques, I still feel that the inking is very much the same as Williamson’s other work, just not as much embellished. I admit that this group and the first one require further study of the techniques used to either confirm or refute my attributions but for now I credit all the inking of Kirby’s pencils for RFTM or Blast-Off to Al Williamson.

In the interview Williamson says that he closely followed Jack’s pencils, as he described it “it’s all there”. My studies seem to support that. Unlike some of Kirby’s inkers, Al does not overwhelm Jack’s pencils, there is never any question that whose penciled it. Most of the effects of Williamson’s inking come from the spotting. It would appear that for RFTM Kirby provided tight line art but left the spotting to the inker. That was the typical technique Kirby used during the Simon and Kirby collaboration. Williamson was a talented artist with great control of his pen and brush work. In my opinion the inking Williamson did was some of the finest ever done on Kirby pencils. Unfortunately the printing used for Harvey Comics in the late 50’s was incredibly poor and some of Williamson’s efforts were lost.

Williamson also claims that someone reworked sections of the stories. “There’s parts that I didn’t ink, because it’s not my drawing or Jack’s drawing”. This clearly indicates that the rework would have happened after Williamson did the inking. However Joe Simon’s collection includes all the original art for the Kirby except for “The Long, Long Years” and I studied them all. Any changes that was done after the initial inking would have to have used white-out or other techniques to remove the original art for replacement with newer work. None of the original art shows any sign that this was done. The only use of white-out or paste-ups was on the lettering. I am sure Williamson believed what he recalled for the interview but it is just another example of the failings of evidence based on memory.

footnotes:

* 40 pages of original art and 11 pages of flats leaving only a single introduction page based only on the printed comics.