I will be right up front about it, this post is about a comic book artist who has at best a tenuous connection to the subject matter of this blog, which is Simon and Kirby. There is a link to Simon and Kirby because some of the Fletcher’s work was published by Fox Comics from December 1939 to March 1941, which overlaps the period when Joe Simon was Fox’s editor (May to July 1940). As I am sure the reader will see, there really is little to suggest that there was any influence in either direction between Fletcher Hanks and Joe Simon or Jack Kirby.

Unless my readers have seen the recent book “I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets!” edited by Paul Karasik, I suspect they will be wondering who the heck is Fletcher Hanks? That certainly was my reaction when I first saw Karasik’s book. As mentioned above, Hanks worked during the early years of the comic book industry, and he did so only on backup stories for smaller publishers. None of the features he created and worked on every achieved anything close to prominence. That explains the forgotten from the title for this post, but the genius part? Well Paul Karasik has described Hanks as “utter, utter genius”, a “visionary genius” and “one of the greatest cartoonists of the 20th century”. High praise indeed, but is it justified?

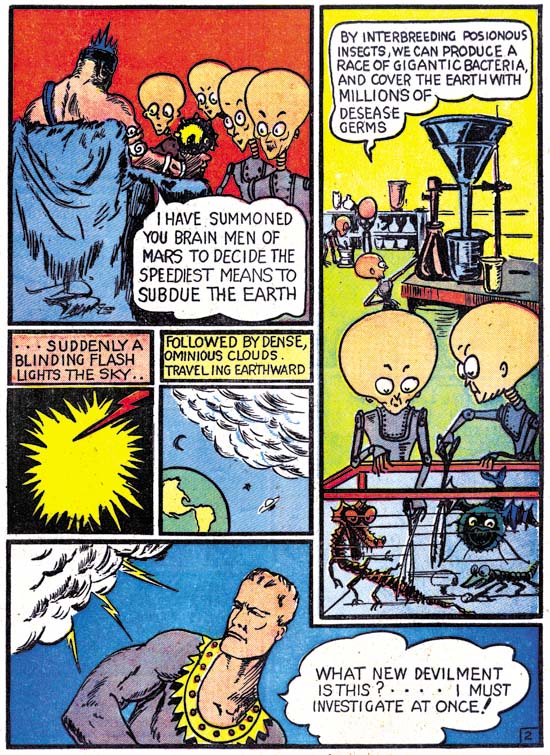

Fantastic Comics #6 (May 1940) The Super Wizard Stardust page 2, by Fletcher Hanks

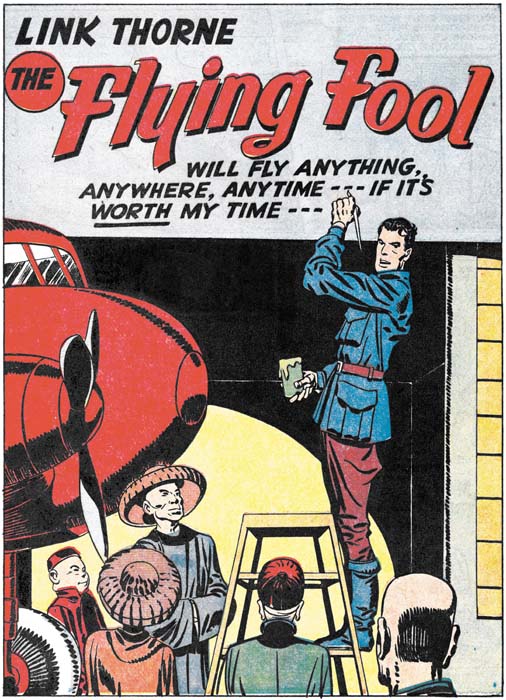

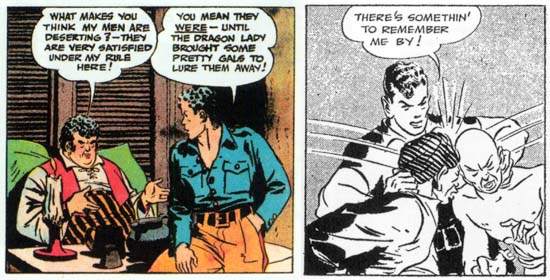

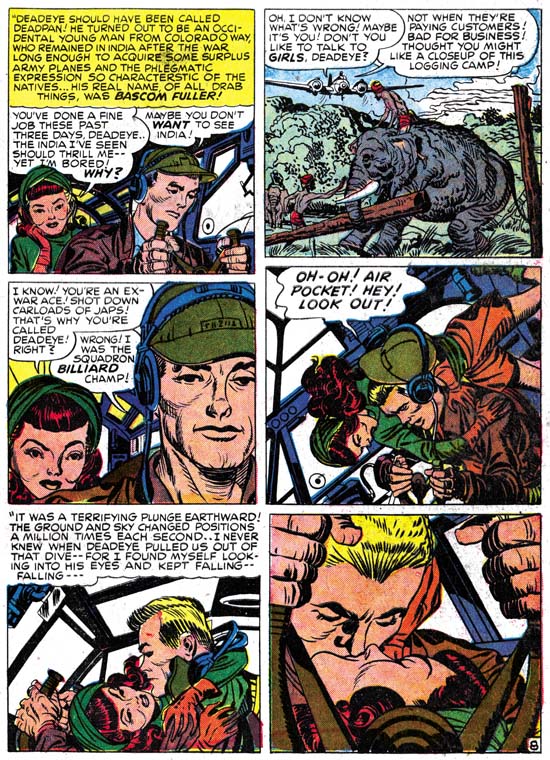

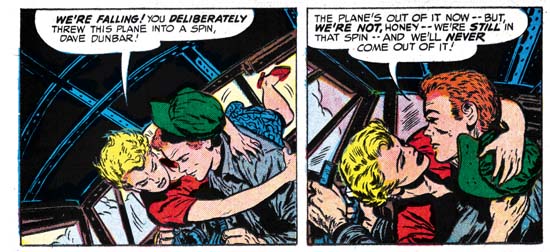

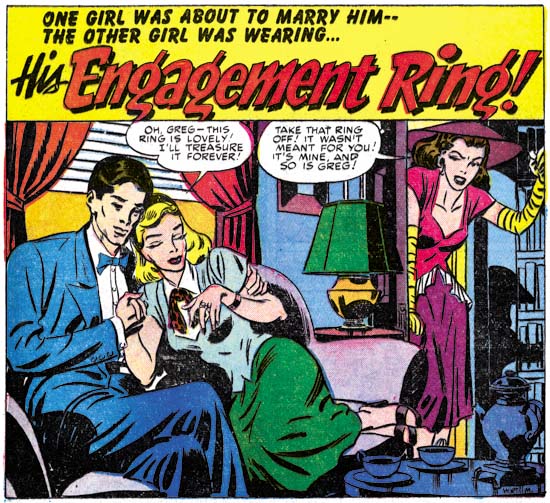

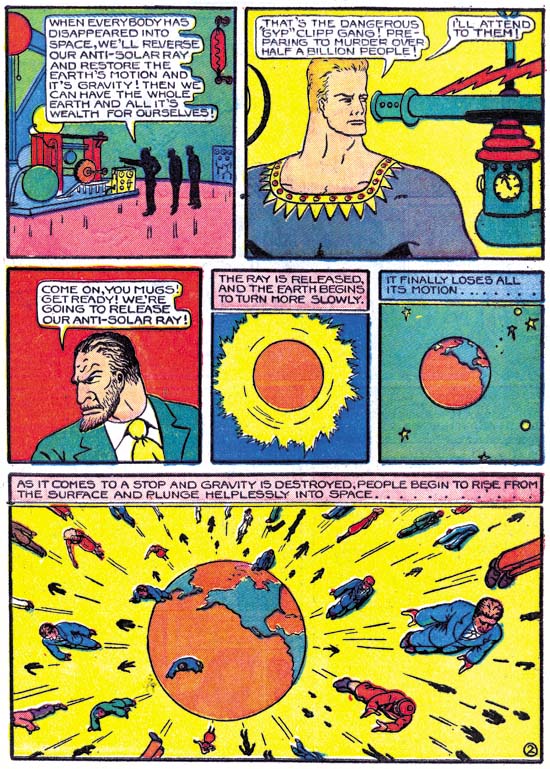

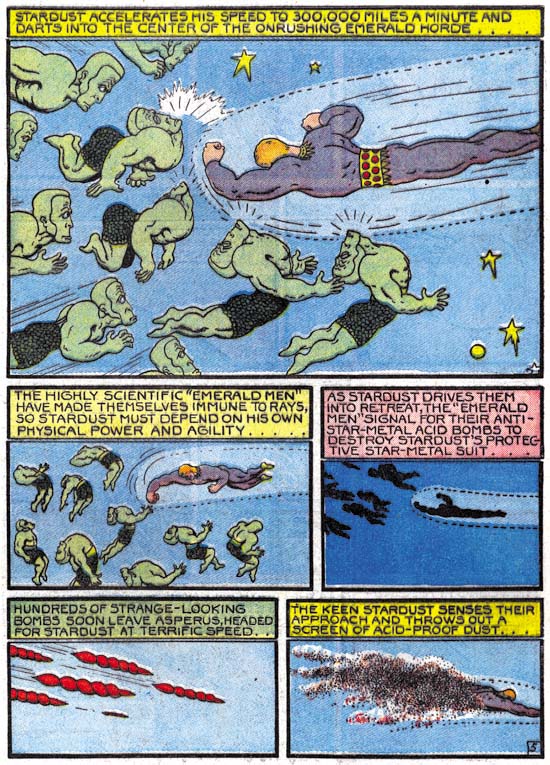

At a glance, Fletcher’s work might be overlooked as just another of the numerous artists who plied their trade during the earlier part of the golden age of comic. Like many of these artists, Hanks drawing is crude with minimal background detailing. This is a misleading impression, a more careful examination reveals with startling and haunting imagery. A giant spider attaching an elephant, the human race rocketing into space as earth’s gravity has been disabled, a superheroine’s beautiful face transforming into one with hideous skull like features. Again and again Hanks shows a vision that is startling and unique. Some of his other forgotten peers have their moments, but none of them as consistent as Fletcher Hanks.

Fantastic Comics #7 (June 1940) The Super Wizard Stardust page 2, by Fletcher Hanks

Even the stories Hanks presents are different form others of the period. The standard hero plot could be summarized as bad guys start executing some diabolical plot, the good guy arrives to save the day and the hero leaves the defeated bad guys for the authorities to handle. Fletcher’s plot summary would be: the hero detects the bad guys plotting, the bad guys unleashed plans have devastating results until the hero arrives to save the day and personally submit the bad guys to some unusual punishment. Hanks’ plotting is therefore refreshingly different, but unfortunately his repetitious use dulls its effectiveness. Fletcher rigid adherence to this plot line sometimes becomes perplexingly illogical. In the Stardust feature the hero resides on a distant star so while his unique monitoring allows him detect the nefarious plots as they are being planned he must still travel great distances to reach earth. This explains why the evil plans are initiated before Stardust can arrive to set things right. Another of his features was Fantomah, Mystery Woman of the Jungle. She also seems able to detect the plans of evil doers, yet despite her great powers and more local presence never seems to stop those plans before they begin. Hanks’ commitment to his standard plot seems so steadfast that he is unable to avoid such illogical story lines. The only way Fletcher seems to be able to break out of his standard plot is when certain elements are simply not appropriate for his hero. One story in the book is about a lumberjack, for such a more human hero there can be no possibility of using special devices to overhear the villain’s planning, it would not be appropriate for the hero to use fantastic powers to overcome the enemy, nor should an unusual retribution play a part, and so Hanks’ lumberman story becomes the more standard hero plot.

Fantastic Comics #8 (July 1940) The Super Wizard Stardust page 2, by Fletcher Hanks

The features that constitute most of Fletcher Hanks’ oeuvre are the Stardust and Fantomah stories that were mentioned above. These heroes have such great powers that the defeat of the enemy is never in question. This was a problem with Superman as well, and once people see these superheroes can do, one wonders why any bad guy would even consider risking crossing their path. Stardust and Fantomah are so powerful that they are not really human but demigods instead. With such a godlike nature it is small wonder that they deal out punishment themselves. And what punishment, it would seem that Fletcher spent as much time devising the punishment as he did on the crime itself. The punishment becomes one of the most rewarding aspects of Hanks’ story telling.

There is much that I have praised about Fletcher Hanks in what I have written above, so do I consider him a genius? Not at all, not even close. I reserve my greatest praise for those who wield their art to provide things that amaze me and yet always seem to remain in control of their talent. For instance, Jack Kirby’s art seems fueled with a wild creative force that drives him to excellence. But no matter how close to the surface that wild urge comes, I always feel it is Jack in control of his creative force and not the other way around. This is not the case for Fletcher Hanks. Although some aspects of his art are very imaginative, for other things, such as his plotting, Hanks seems unable to break out of the most obvious constraints. Some of the impact his most startling illustrations is derived from the repeated use of certain elements. The minimalist artists have shown that such repetition can be visually very powerful. But such repetition also reminds me of the work of Charles Crumb, Robert’s brother. Charles’ work is disturbing, when viewed it is quickly apparent that it is the work of a disturbed mind. Charles Crumb’s use of repeating elements seem more the result of a compelling obsession rather then something that he had any control over. I find a similar effect, although to a lesser extent, in Fletcher Hanks’ art as well. Paul Karasik’s research has provided the clue to help with the explanation, Fletcher Hanks was an abusive alcoholic. I once knew a man with what I judge to have been a similar personality. The man’s abuse was never directed at me, almost certainly because my father was one of the few individuals he feared. The man I am recalling was not an artist but he had an amazing mind. When he was not in a mean mode he was a fascinating person to talk to. Some of his concepts were quite brilliant although perhaps not always true. Like Hanks, certain of his thinking seemed trapped in ways that I think were clear to others but I am sure he never truly understood. He could no more escape them then he could the alcohol that lead to so much misery for the people around him. Would I have made the association between Fletcher Hanks’ alcoholism and his art if Karasik had not revealed it? I do not know, but now that the link has been made I cannot banish it.

There is one aspect of Karasik’s comments about Hanks that really bothers me. Karasik puts much emphasis on the fact that Hanks’ did all the work himself; the writing, drawing, inking and lettering. He is critical of the “assembly line” method he ascribes to most of comic book work where these different jobs were executed by different individuals. This concept that all the truly great artists are those who create the work by themselves can be found in the fine arts as well, but it is by no means a universal opinion. Although I recognize the importance an artist own hand may bring to a work of art, I am unwilling to limit my esteem to such art. To do so would mean rejecting things such as Japanese wood block prints or even Renaissance painting. What bothers me is not so much as the difference of opinion about this subject between Karasik and myself, as much as how it demonstrates Karasik’s ignorance of comic book history. The fact is during the time Hanks worked on comics it was not at all unusual for the creator to perform all creative aspects. At the start of the boom that followed the release of Superman with Action Comics #1, it was the norm for an artist to write, draw, ink and letters a story himself. The earliest work by Jack Kirby or Joe Simon was done this way as well. The only difference for Fletcher was that he was not working in comics afterwards when the single writer/artist became the exception not the rule.

I may not consider Fetcher Hanks a genius, but I agree with Karasik that his work should not be enjoyed as some sort of campy entertainment. It is powerful stuff and quite worthy of being read. Karasik has done a great service in raising Fletcher Hanks from forgotten obscurity, I fully recommend “I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets”. At $20 it is a steal, the original comics are so rare that I doubt you could find a single one of them, no matter how beat up, at that price. The contents are not at all cheap. The stories are nicely restored scans from original comics using a technique to clean them up that is similar (if not identical) to the one I use. The results are printed on flat paper and are absolutely gorgeous. I think they are better done then the “Terry and the Pirates” reprint that I recently positively commented on. I have long felt that this was the way to reprint old comic material. I wonder if Marvel and DC will ever wake up abandon their method of bleaching and recoloring.

There is a special bonus found in this book, Paul Karasik provides an afterword about Fletcher Hanks. Not your ordinary afterword, but a graphic story instead about Karasik’s research of Fletcher Hanks and what he learns. It is a well written and drawn short story that is almost worth the price of the book by itself. Karasik has admitted to not being very productive but this afterword indicates that is not due to a lack of talent. I intend to try to locate some of his earlier efforts and hope he exerts himself more as a graphic storyteller in the future.