I had previously discussed how crime by women was handled by Simon and Kirby (Crime’s Better Half). However here I would like to briefly discuss the criminal couple, much rarer perpetrators of crime in Simon and Kirby or real life. The most famous today would be Bonnie and Clyde. Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow and other members of their gang were active between 1932 and 1934. It was the fact that they were a couple that projected Bonnie and Clyde into national infamy. The gang really were not very talented criminals. They only rarely robbed banks and never got much for their efforts for their few attempts. Generally Barrow gang robbed smaller institutions like grocery stores and gas stations. They were cold blooded killers quick to use their weapons against lawmen or civilians alike. Frankly the Barrow gang without Bonnie would not a received much attention outside of Texas.

The real Bonnie and Clyde hamming it up (1933)

During one quick get-a-way, the Barrow gang left behind a some rolls of film. The photographs that came from the developed film were sensationally. Among them were shots of Bonnie holding up Clyde at gun point and another of Bonnie with a cigar and a gun. These photos of the gang fooling around were just that, nothing more than fiction. Bonnie did not participate much in the actual crimes and she did not smoke cigars. But the photos provided a lot of national publicity and played an important part in the legend that followed.

Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty from Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

And Bonnie and Clyde did become a legend with two movies and one made for TV movie; the Bonnie Parker Story (1958) and the more important Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Bonnie & Clyde, the True Story (1992). Eighty years later they are still well known.

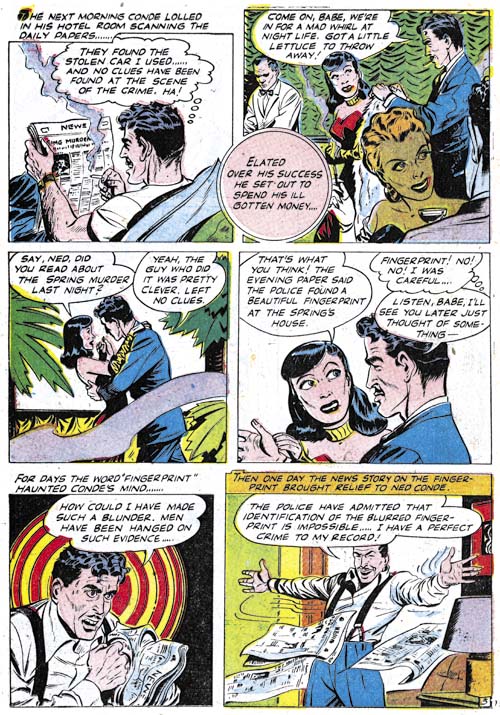

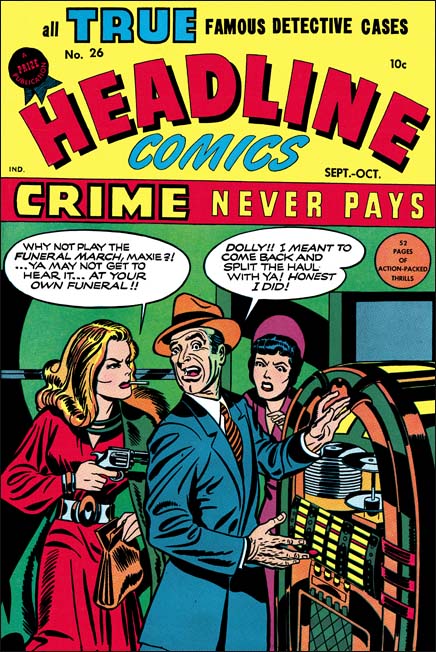

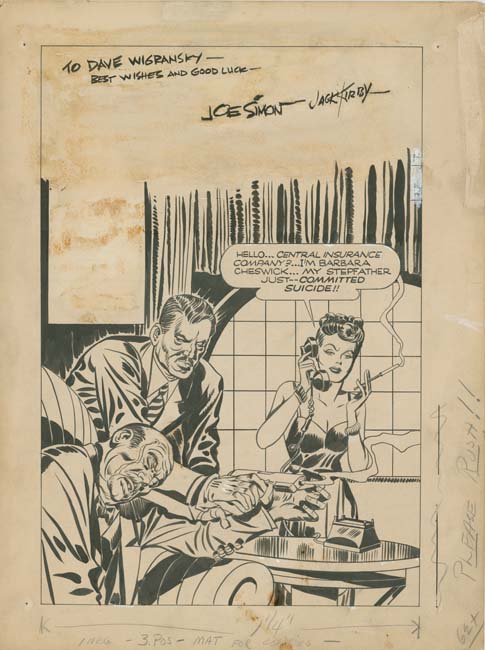

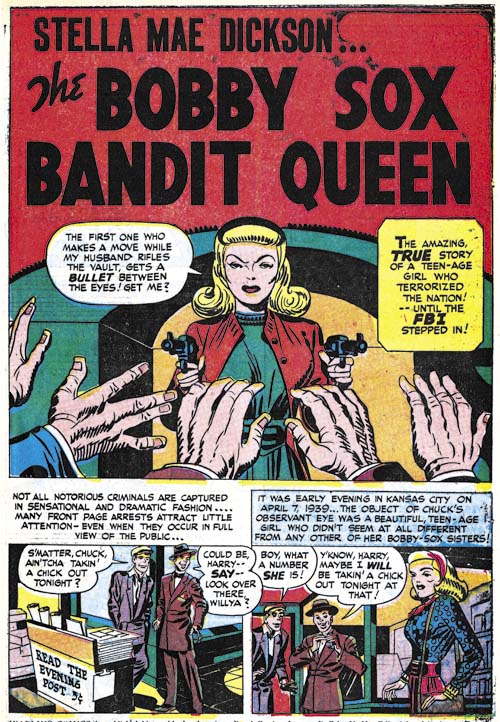

Headline #27 (November 1947) “The Bobby Sox Bandit Queen”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

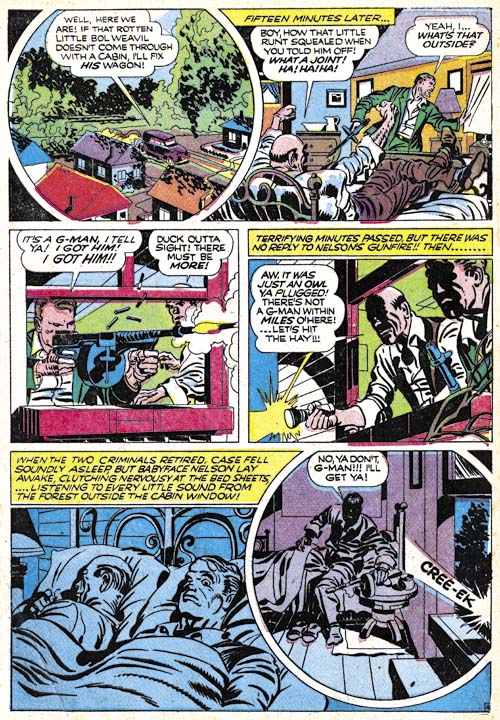

While Bonnie and Clyde may have been the most famous criminal couple Simon and Kirby never featured them in any crime comic. There was, however, another criminal couple that were made into a Simon and Kirby story; Stella Mae and Bennie Dickson in “The Bobby Sox Bandit Queen” from Headline #27 (November 1947). Stella and Bennie were not as famous (or infamous) as Bonnie and Clyde. They were reported in the press of the day but as far as I know no movies were ever made based on them. But in many ways they were a much better criminal couple then Bonnie and Clyde. For one they were much more successful in robbing banks. In one bank hold up they got away with about $47,000. Not bad by today’s standards but pretty good during the depression and much better than the Barrow gang ever did. One bank robbery by Bonnie and Clyde got them $115. And while Bonnie posed with a gun for pictures but was not really participate much in the actual crimes, Stella was very handy with a gun and a big asset in the robberies. In fact her sharp shooting of a police car’s tires during a chase allowed the criminal couple to make a clean get-a-way.

It is easy to see why Simon and Kirby picked Stella Mae and Bennie for a story but why did they never do a story on Bonnie and Clyde? Could it be the rather gruesome end that Bonnie and Clyde had under a barrage of bullets? Seems doubtful since Joe and Jack had depicted similar deaths in the past and did show Bennie Dickson’s comparable end. No, I think the real reason Bonnie and Clyde were off limits as far as Simon and Kirby were concerned was due to their marital status, or more precisely lack thereof. Stella Mae and Bennie were legally married, Bonnie and Clyde were not. That Bonnie and Clyde were unmarried, romantically involved and living together added spice to their story. But while that sold papers it was not the sort of thing that many would consider appropriate for a young audience. Dr. Wertham may have declared that comic books corrupted their youthful readers but Simon and Kirby were really more careful about what they included in the comic stories they created than their critics would admit. Still I would have loved to have seen what Simon and Kirby would have done with Bonnie and Clyde.