(August – October 1950: Young Romance #24 – #26, Young Love #12 – #14)

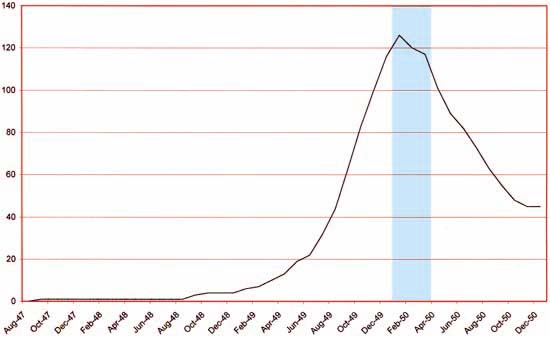

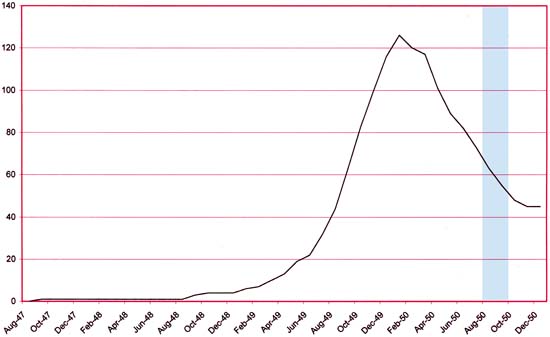

Number of Romance Titles 1947 – 1950 (the period covered in this chapter shaded in blue)

The trend of the decreasing number of romance titles that was found in the period covered in the previous chapter has continued. As far as can be judged the Prize love comics, Young Romance and Young Love, were still successful; at least enough to continue on a monthly schedule. Young Romance is now entering its third year of publication. The most obvious change is that Young Love replaced the previous photographic covers with drawn versions for the August issue and Young Romance would follow a couple months later. Frankly I am unclear what drove the use of photos on comic covers but as we will see in future chapters the use of art covers would be temporary for Young Romance and a little more extended for Young Love. Printing is somewhat more expensive for photographic covers but according to Joe Simon for the publication sizes involved the extra cost was very minimal.

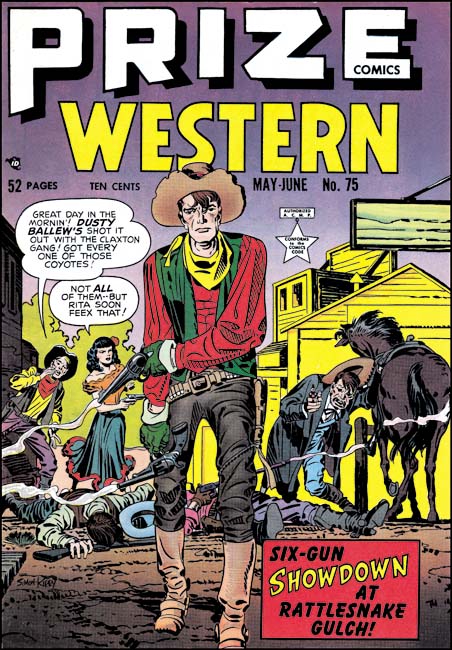

I have noted in previous chapters a decrease in the number of artists used in producing YR and YL. This trend continues to the extent that a total of six artists were used in the six issues issued during the period covered in this chapter. In fact this is the first period that I have covered in this serial post where I can confidently identify all the artists involved (or as confidently as I can where Bruno Premiani is concerned). The drop in the number of contributing artists is not random; it is the less talented artists that are no longer used. Some, like George Gregg, would continue to appear in the Prize crime comics (Headline and Justice Traps the Guilty). There is one exception to dropping the less talented artists and that is John Severin. Although Severin does not show up in any of the comics from this period he has not yet been truly dropped as he will appear again in the next chapter. In any case as talented an artist on western stories that Severin was he really was not very good at romance stories. His diminished appearances in the romance titles seemed to have been offset by his work for Prize Comics Western.

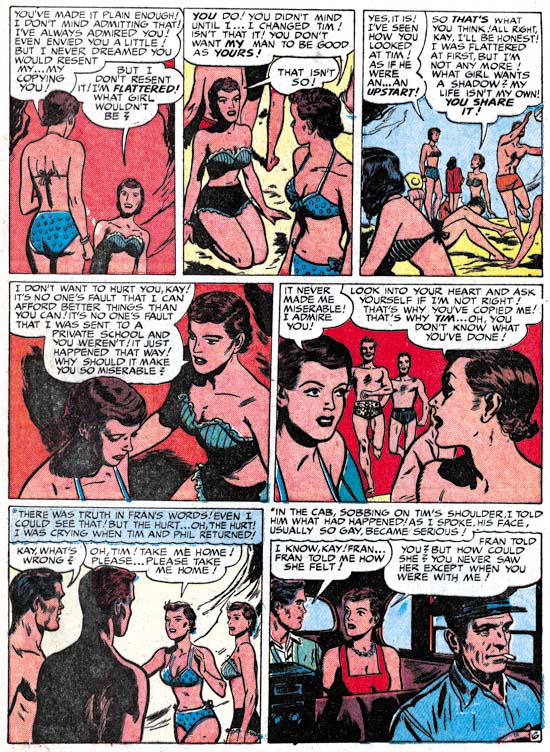

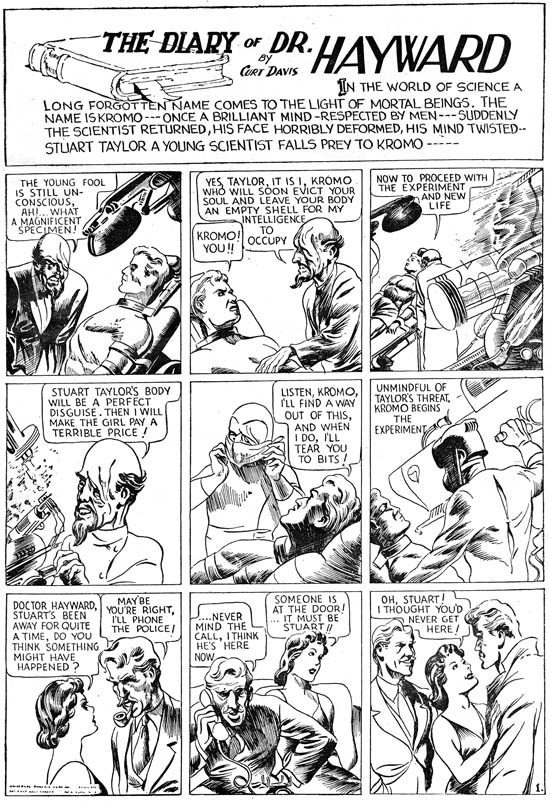

Young Love #13 (September 1950) “Everybody Wants My Girl”, art by Jack Kirby

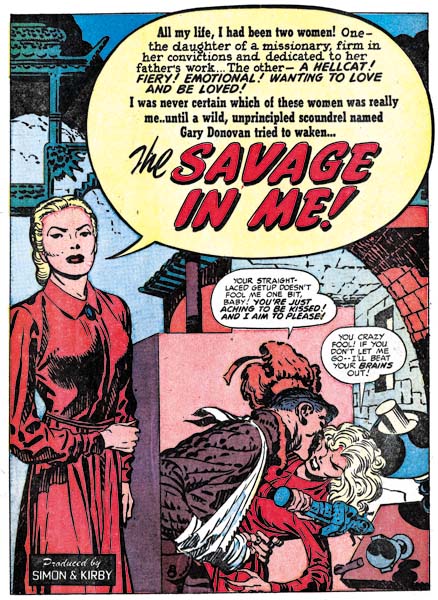

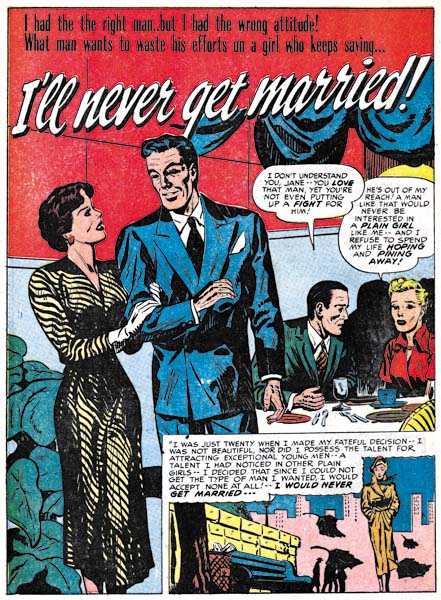

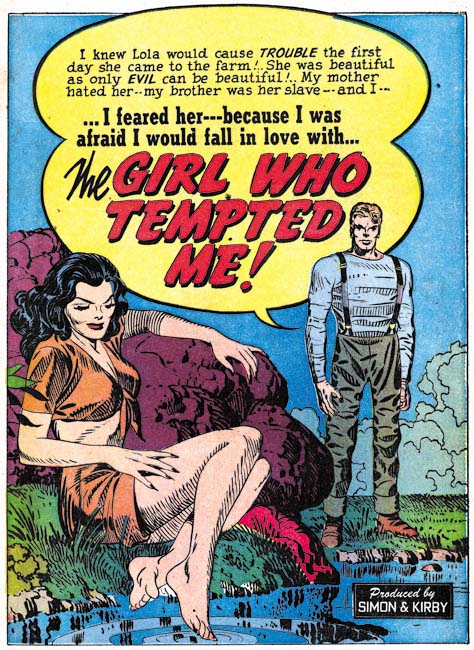

Jack Kirby would be, as he has been, the primary artist for the Prize romance titles. In these six issues he provided 4 covers, 7 stories and a total of 62 pages. Jack would do all the lead stories for Young Romance and one of them for Young Love. These lead stories would start with a confessional splash (where someone is introducing the story and their speech balloon is used for the title). All but one of the splashes would be half page designs and none of them had quite the punch as those from the earlier issues. Perhaps this is because Simon and Kirby’s creative juices were directed elsewhere but that will be discussed in a separate post.

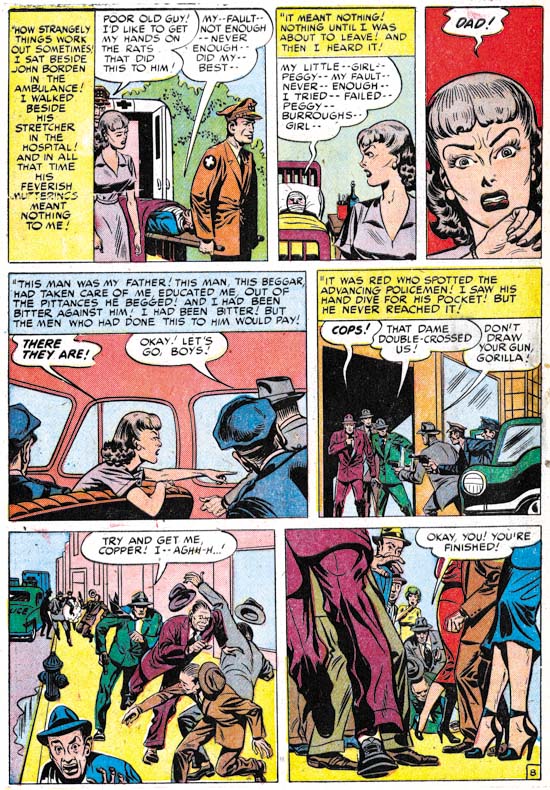

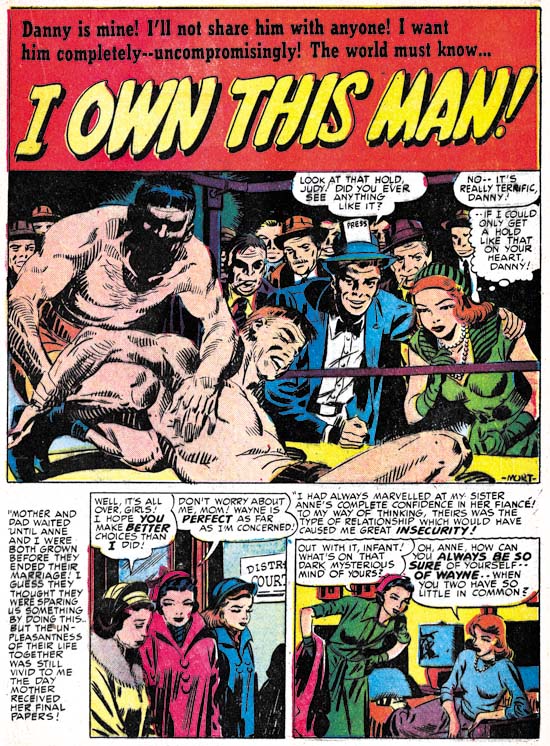

Young Romance #24 (August 1950) “Buy Me That Man” page 14, art by Jack Kirby

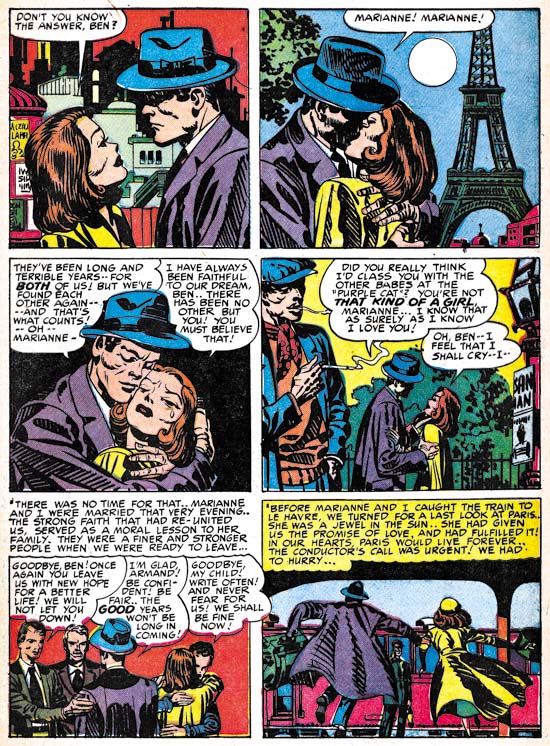

Jack Kirby drew a lot of romance stories and it is clear he had a hand in plotting these stories as well. So it is not surprising that some plot devices would be used more then once. The use of an sudden plunge in a plane to throw a couple into each others arms found in YR #24 (see above) was used previously in YR #8 (November 1948 “Love Can Strike So Suddenly”, see Swiping off of Kirby). It would be found again in In Love #2 (October 1954, “Marilyn’s Men”). While Marilyn’s Men was mostly drawn by Bill Draut, Jack probably was involved in the plotting of that as well.

Young Love #14 (October 1950) “Girls like Her”, art by Mort Meskin

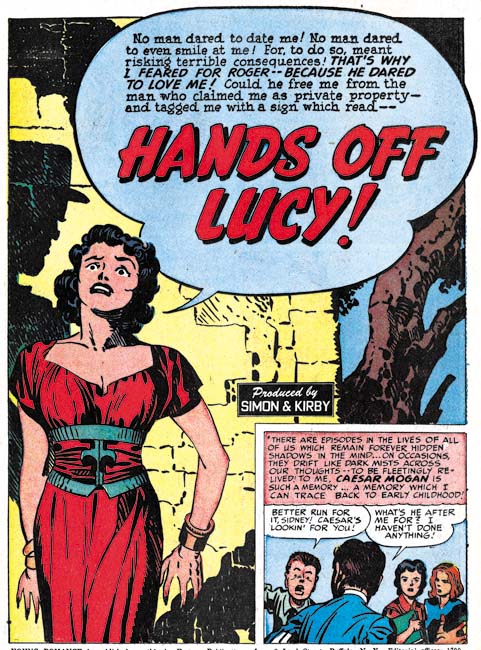

As with last chapter, Mort Meskin would be the second most used artist for this period drawing 14 stories with 54 pages. While the number of features is doubled that done by Kirby most of them are very short, 1 to 3 pages long. Previously these featurettes were done by a number of different artists but during this period Mort did all but two of them (the two Meskin did not do were done by Kirby). Mort would provide one of the lead features (Young Love #12).

Young Romance #24 (August 1950) “Take a Chance”, art by Mort Meskin

Although I have not found any evidence that the more talented artists working for Simon and Kirby were ever supplied layouts for the stories they drew, Joe and Jack did seem to be involved in at least the plotting of the scripts. Therefore recurring themes would also show up among other artists. The theme of a woman’s love of a racecar driver and the fear of the risks involved in that occupation can be found in “Take a Chance” shown above. It also would return many years later in a cover a story drawn by John Prentice (“Take Me as I Am”, Young Brides #14, April 1954).

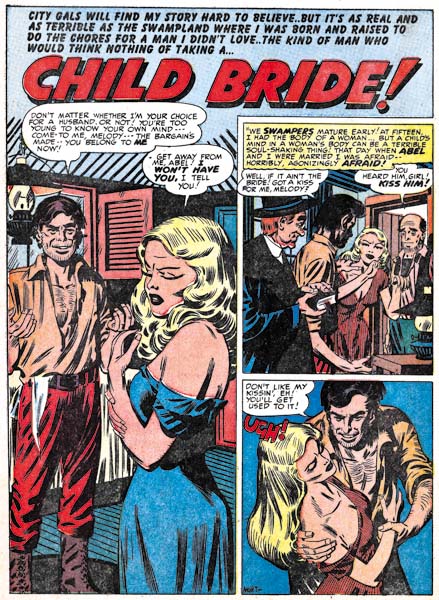

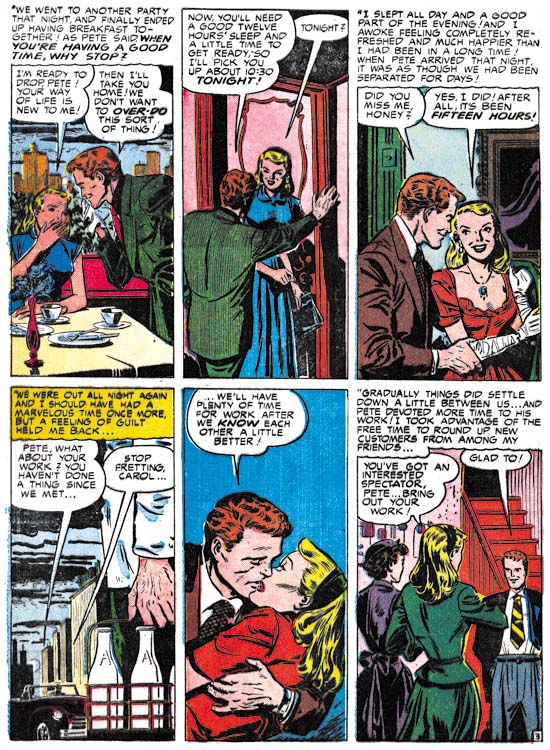

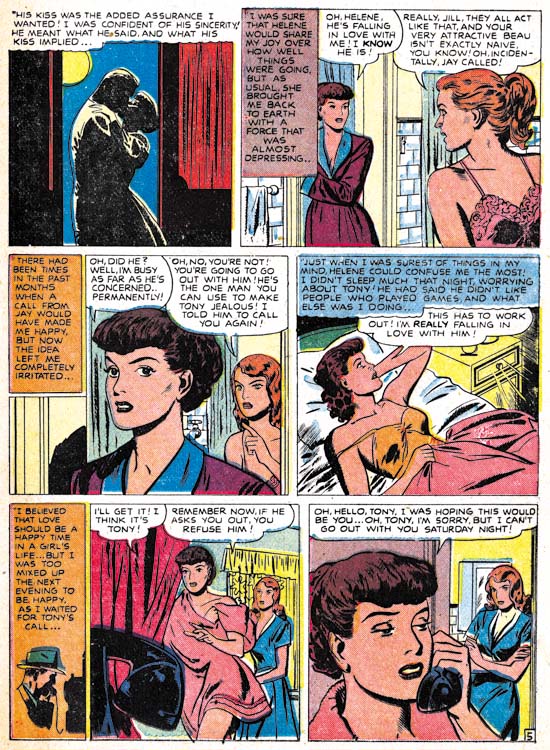

Young Love #14 (October 1950) “I’ll Tell You No Lies”, art by Bill Draut

Bill Draut continues in the number three spot with 6 stories and 46 pages but as we shall see he barely holds that position. At this point Draut arrives at a style that will not change very much for the rest of the work that he would do for the Prize romance titles or for that matter Harvey’s love comics as well. I do not say that disparagingly as he has a clean style and is good at portraying body language. Bill generally uses half page splashes so I have provided an image from “I’ll Tell You No Lies” even though it is well below Draut’s usual quality.

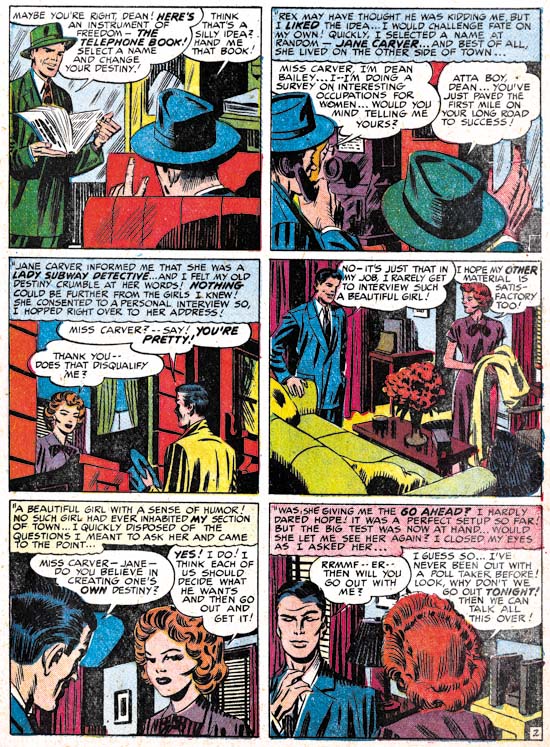

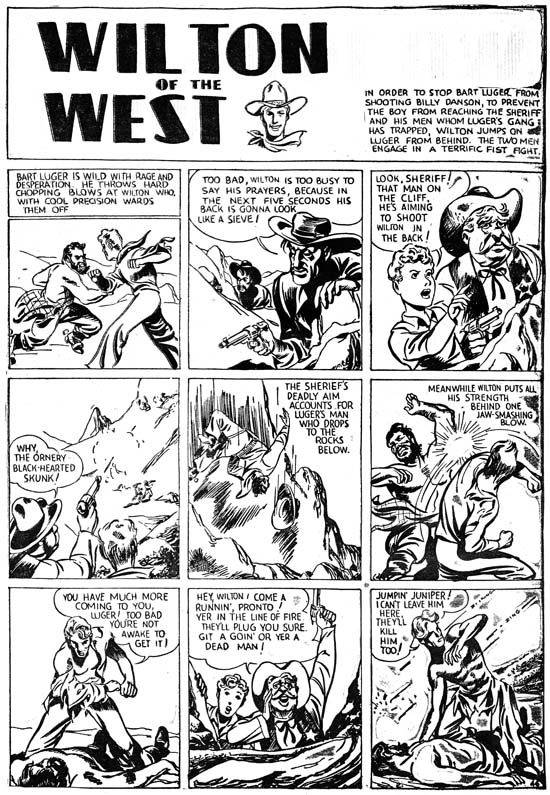

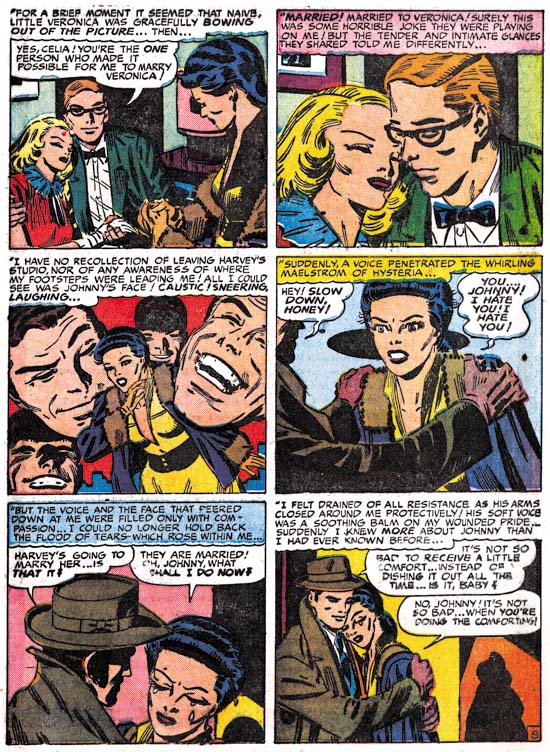

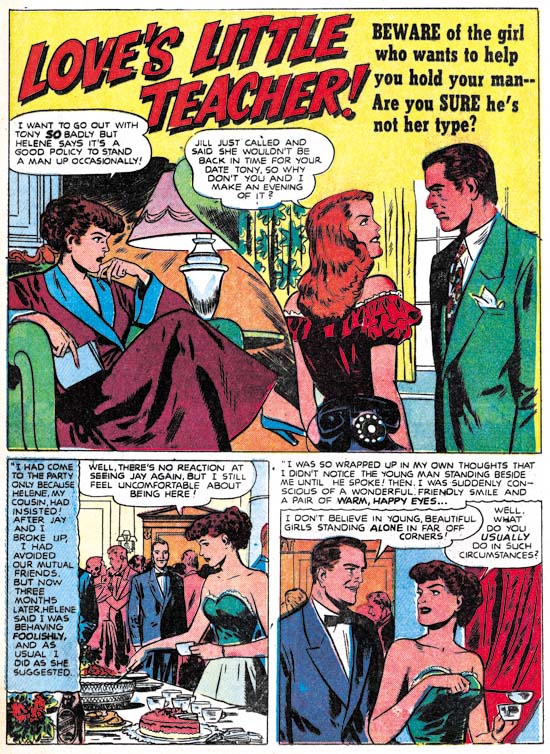

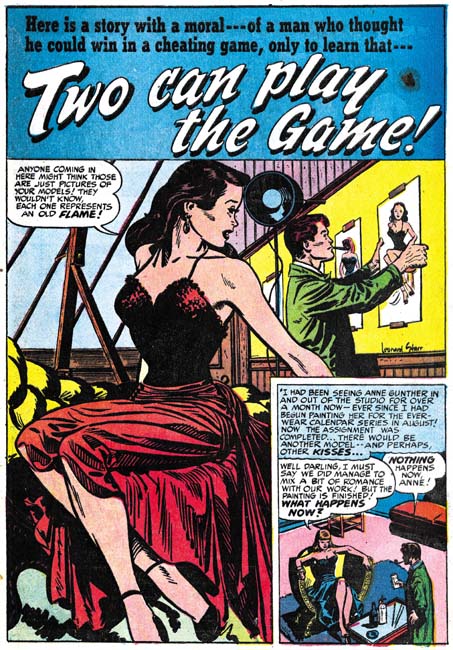

Young Love #13 (September 1950) “Two Can Play the Game”, art by Leonard Starr

Leonard Starr was used often during this period with 6 stories and 45 pages, only one page less the Bill Draut. Starr had his own style of inking but compare the brush work between the man’s jacket and the woman’s dress in the splash for “Two Can Play the Game”. The inking on the man is typical of Starr but the picket fence crosshatching found in the dress is not. This looks like typical S&K studio style inking and suggests that either Joe or Jack did that particular spotting. I am not sure why this was done but it was not that unusual for studio style inking to appear in splashes that were otherwise inked by the artist.

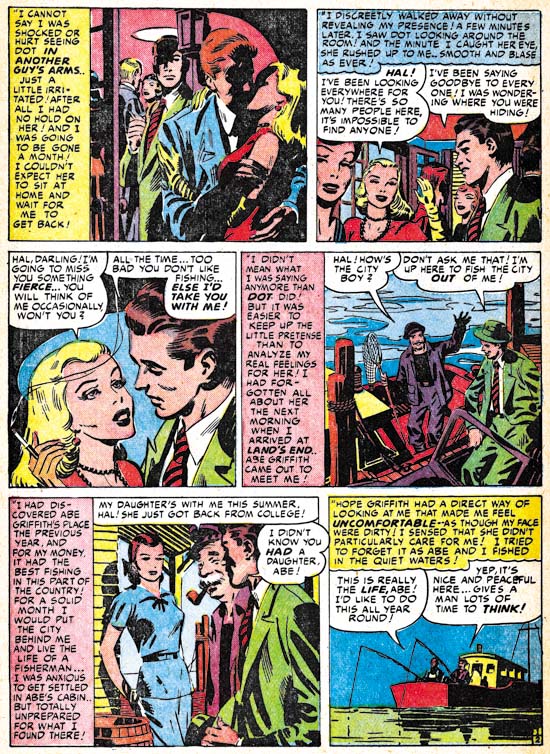

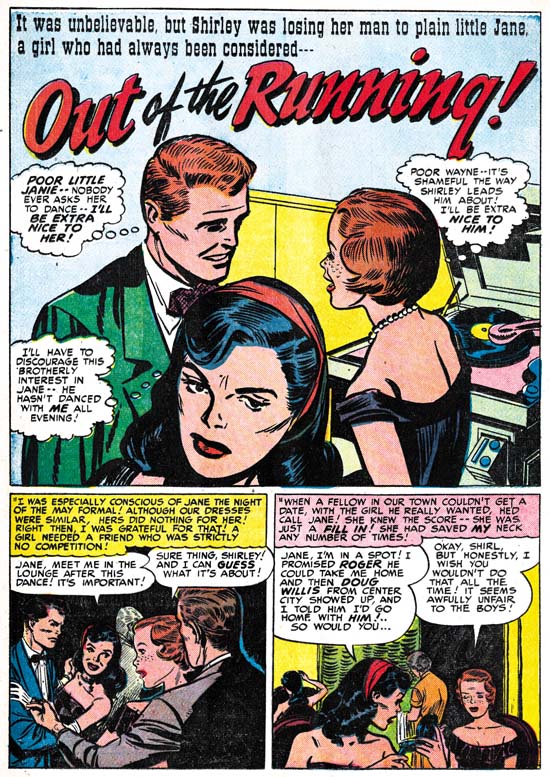

Young Romance #25 (September 1950) “Out of the Running”, art by Leonard Starr

In two stories from this period (“Out of the Running” YR #25 and “Hired Wife” YR #26) Starr introduces a new type of beauty. Previously his women a pixie or elfin look to them; wide foreheads, widely separated eyes, smaller mouths and narrow chins. The pixie look can still be found in some characters in these stories but there are also women with larger eyes, smaller foreheads, and fuller lips giving them a more sultry appearance. This new type of beauty will play an important part in the syndication strip “Mary Perkins on Stage” that Starr will launch in 1957.

Note the inking on the man’s jacket in the splash panel. The shoulder blot and blunt brushwork is not typical of Starr’s inking. Once again Simon or Kirby has step in as art editor to alter the art. This splash is actually based on a stat of a blowup of a story panel. The panel chosen was one of Starr’s tall and narrow ones that had to be expanded on both sides to accommodate the more horizontal splash panel. Most of the jacket was not present in the story panel and the inking was touched up even in that portion that was original present. Although this technique of using a stat in the creation of comic book art is rarely found in Simon and Kirby productions it was a method that would be turned to when needed. I suspect that Joe and Jack were unhappy with Starr’s original splash.

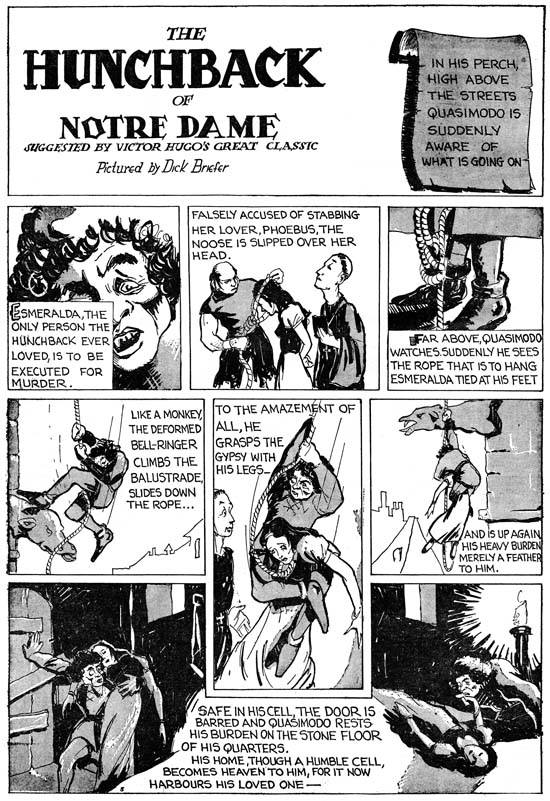

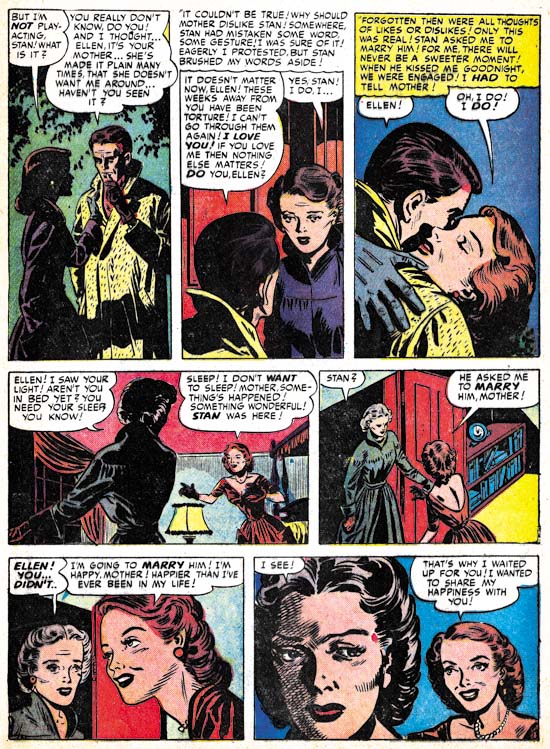

Young Romance #26 (October 1950) “Hired Wife”, art by Leonard Starr

Above is the splash page for the other example of Starr’s more sultry beauty. This story is unusual in that the tall narrow panel that is found in all previous stories by Starr occurs only in the splash panel of “Hired Wife”. I am not sure what to make of this change in panel layouts but it suggests that he may have been working from someone else’s layouts. I will return to this subject in the next chapter of this serial post where we will find another example.

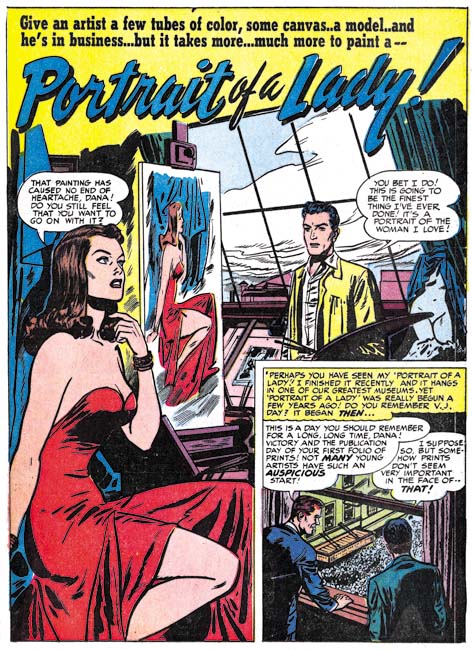

Young Romance #24 (August 1950) “Portrait of a Lady”, art by Bruno Premiani?

Bruno Premiani(?) has been a persistent presence in Simon and Kirby productions since August 1949. During this period Bruno provided 3 stories and 26 pages. While he did not appear as much as Kirby, Draut or Meskin what art he did was all first rate work. The romantic interest between an artist and his model is a recurring theme in Simon and Kirby productions. It is found in the very first cover for Young Romance (The First Romance Comic) and can be found many years later as well (Artist and Model). The artist and model theme appears to be particularly popular for this period since it occurs in three stories. We have previously seen Leonard Starr’s splash from “Two Can Play the Game” (see above) now we can compare it with Premiani’s version “Portrait of a Lady”. For me this is not a question of which was the better artist but rather individual interpretations from two talented practitioners of comic book art.

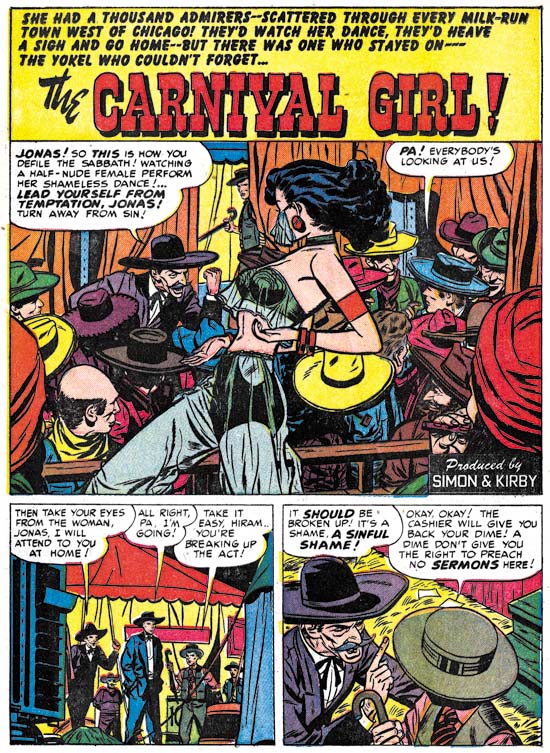

Young Romance #26 (October 1950) “Simpson and Delilah”, art by Bruno Premiani?

Premiani repeats the use of a dancing woman for the splash of “Simson and Delilah” (a south Pacific dancer graced “Untouched” from Young Love #10, June 1950). Although this is a repeat performance of the theme it is by no means a duplicate of the previous version.

This would be the last romance story that Bruno Premiani(?) would do for Simon and Kirby. As I have mentioned in the past this body of works were all unsigned in Simon and Kirby productions and were done in a style dissimilar to that used in art done for other companies that were signed by Premiani. While this does not disprove that the artist was Bruno Premiani it does beg the question as to why he was originally credited with this work. Although I am hesitant to fully accept Bruno Premiani as the artist (hence my use of question marks) I have no doubts as to the talent of this creator. His absence would leave a hole in the romance titles that would not be filled for some months to come.

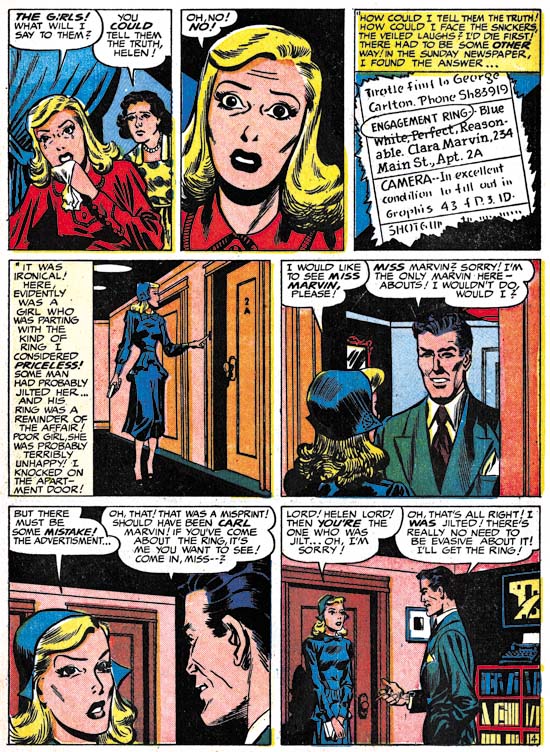

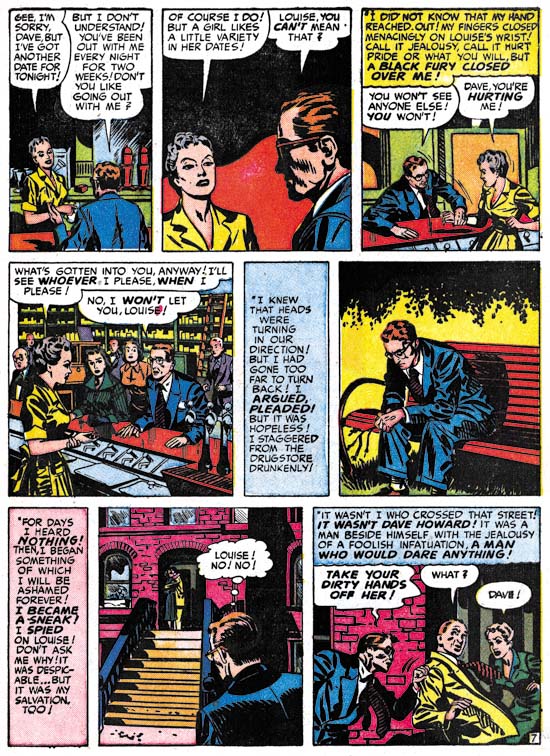

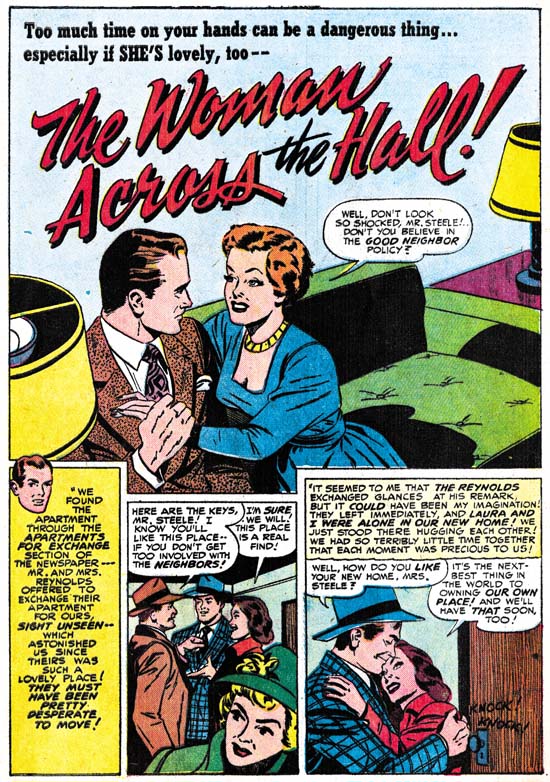

Young Love #13 (September 1950) “The Woman Across the Hall”, art by Vic Donahue

Vic Donahue played a minor part in the romance titles of this period providing only 2 stories with 15 pages. His art is improving both in his in his ability to depict figures and to graphically tell a story. His women in particular have become more interesting largely because his use of arching eyebrows brings more emotion into their faces. My database indicates that these are Vic’s last work for Simon and Kirby but I hesitate to say that with conviction until I had a chance to more carefully review future issues. In any case I do not feel the same about Donahue’s absence then I do about Premiani’s disappearance.

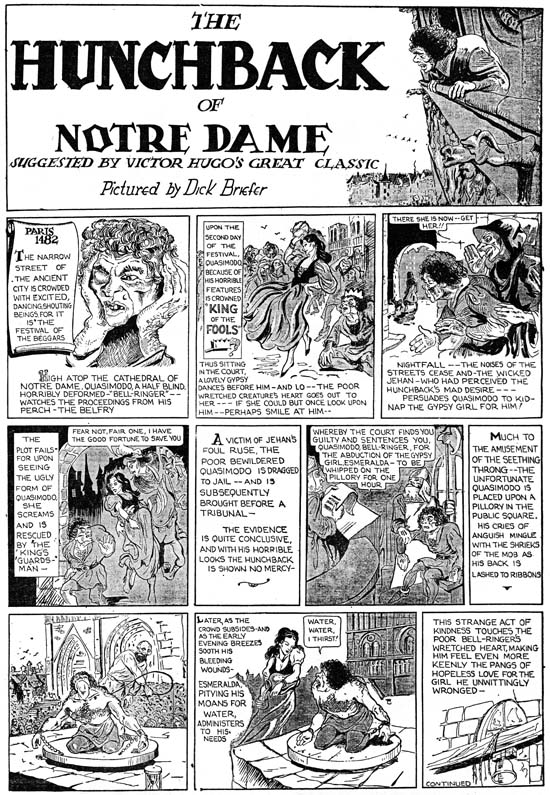

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)