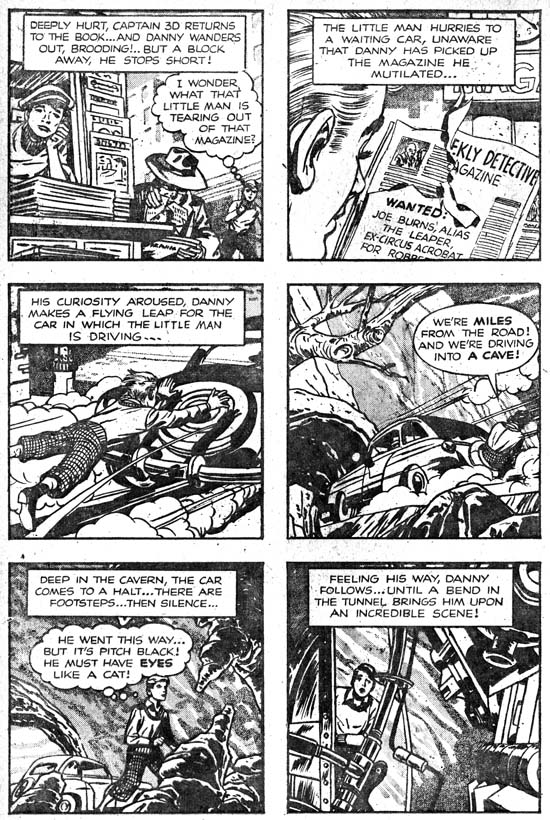

(Justice Traps the Guilty #3 – #5, Headline #29 – #31)

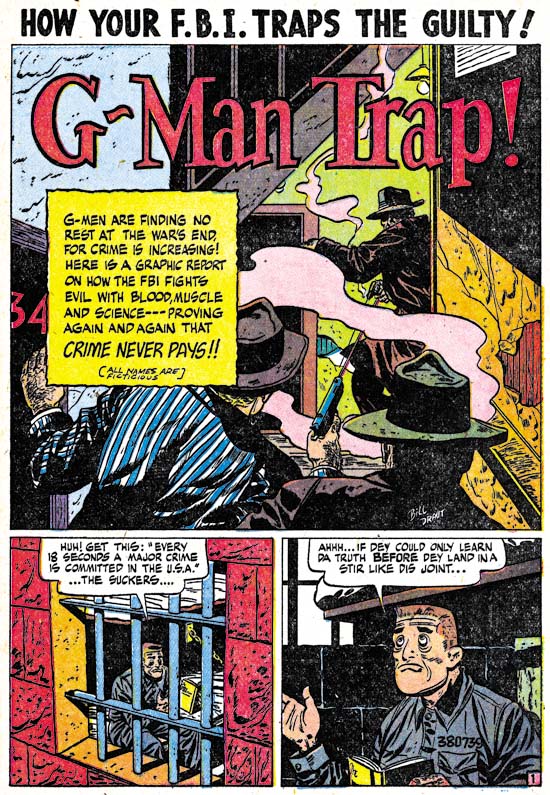

Jack Kirby remains the principal artist for the six crime issues discussed in this chapter. All 6 covers were drawn by Jack as well all the lead stories. Kirby’s did 10 stories with a total of 117 pages (including the covers). However Bill Draut now assumes a more important roll becoming the second principal artist. Bill supplied 11 stories, one more then Jack, but fewer pages (81 pages). The other three artists contributed much less then either Jack or Bill. The next most prolific (A. C. Hollingsworth) drew just 3 stories with 25 total pages.

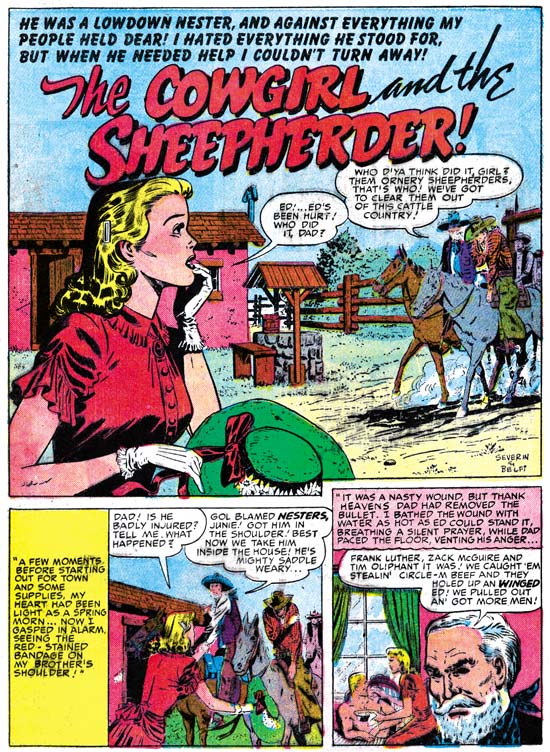

Justice Traps the Guilty #4 (May 1948) “Queen of the Speed-Ball Mob”, art by Jack Kirby

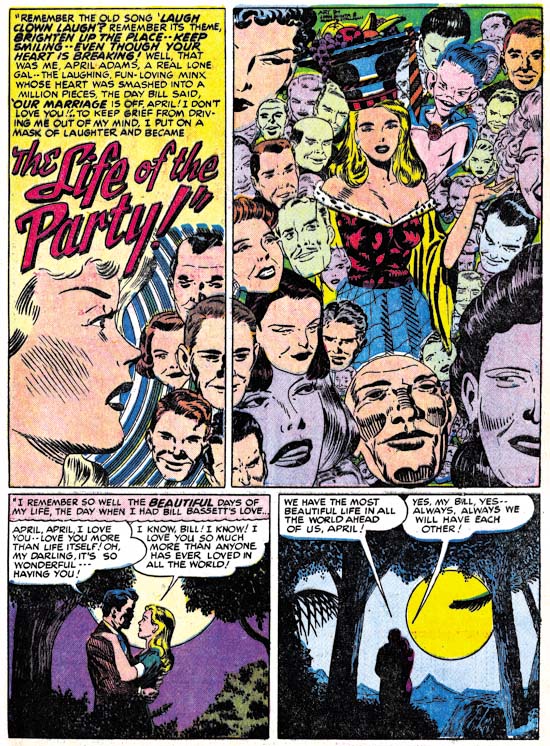

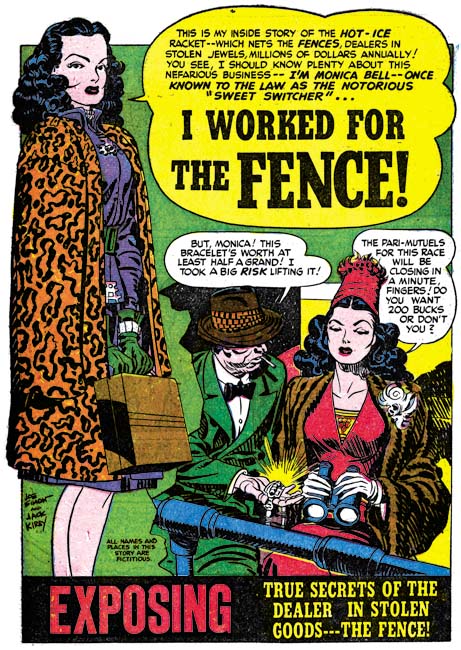

The first story consistently uses the motif of a character introducing the story with the word balloon forming the title caption. I have noticed that when a story is being narrated, it is often by a woman. Almost certainly this was because male criminals generally have fatal endings (and therefore would not be able to tell their story) while females normally survive.

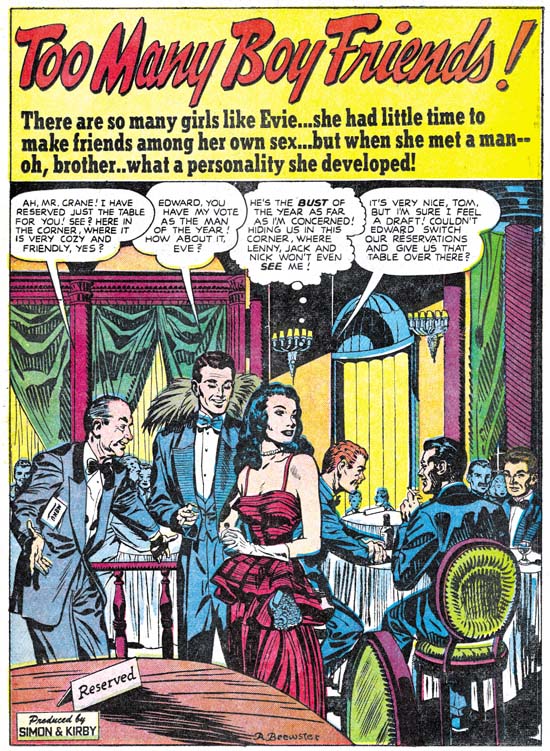

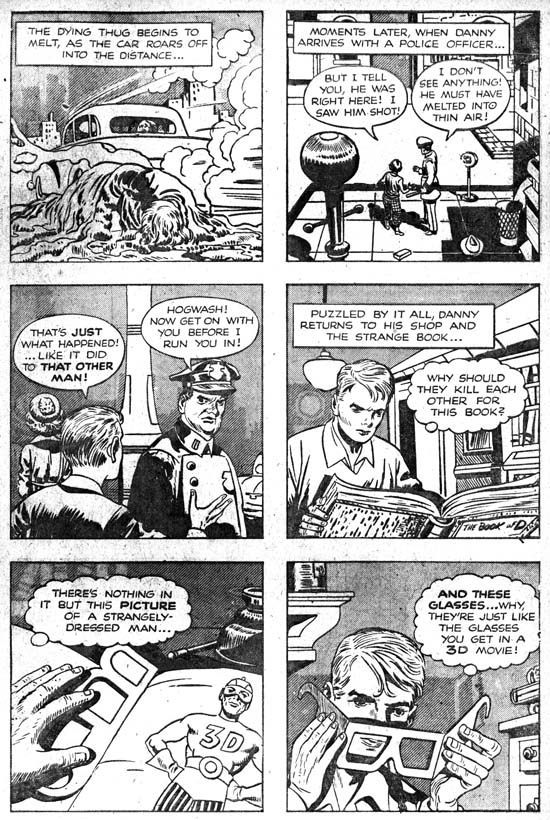

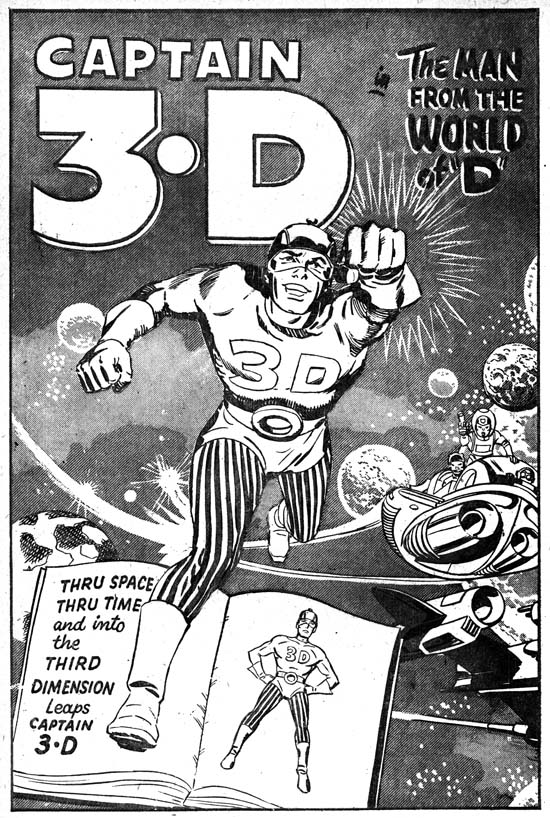

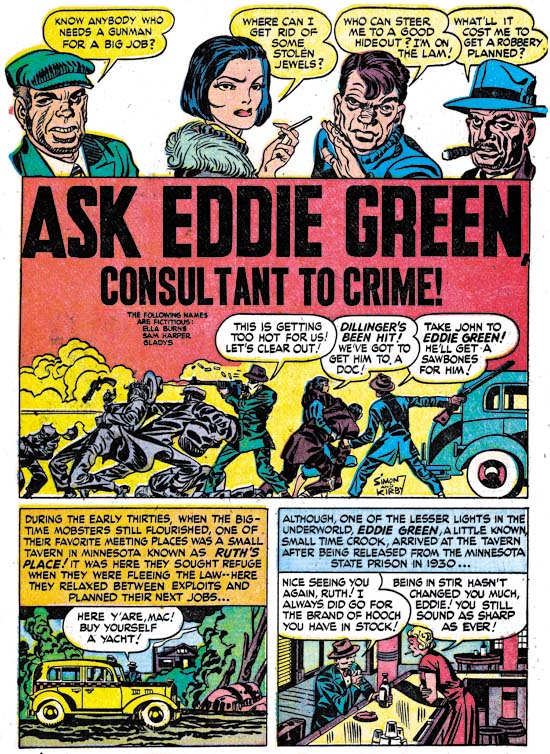

Justice Traps the Guilty #3 (March 1948) “Ask Eddie Green, Consultant to Crime”, art by Jack Kirby

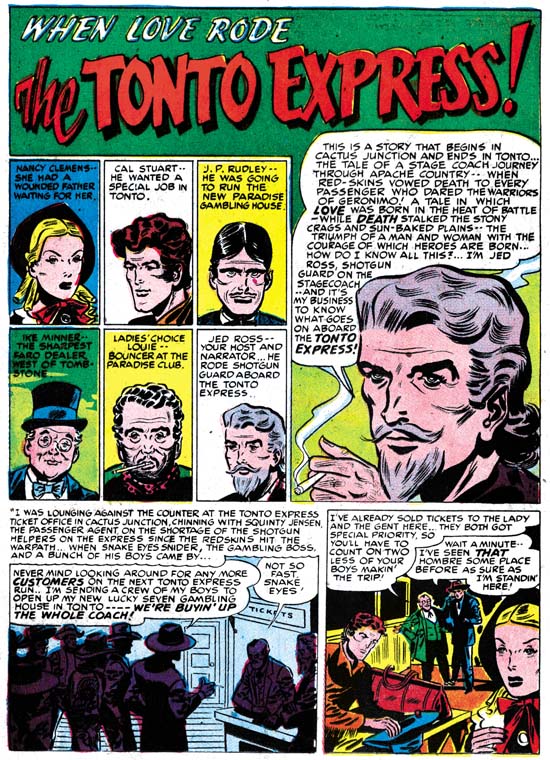

A motif that would occur often in Kirby’s splashes at this time was having a cast of characters make a series of statements to introduce the story. Actually it was a return to an old technique as we have seen it as far back as in Captain America. When used in a splash covering two thirds of the page, this type of design did not leave much room but in “Ask Eddie Green” Jack makes effective use of what is available by supplying a small shoot out scene. The depth of field is so narrow that the results look like a frieze. Despite the small size everything is clear and the scene is filled with interest.

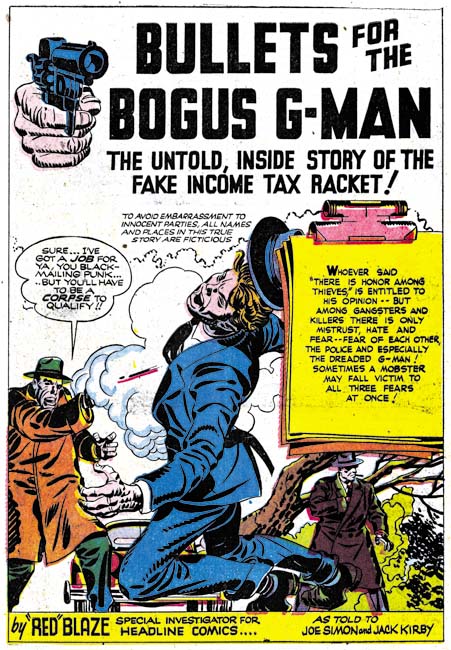

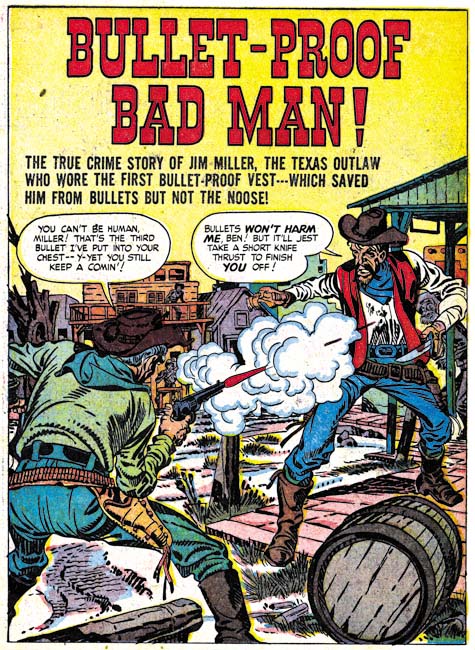

Headline #30 (June 1948) “Bullet-Proof Bad Man”, art by Jack Kirby

Perhaps it is just my tastes, but I feel that Kirby’s splashes are not as exciting as before. This may have been a result of Kirby’s declining use of full page splashes. Only 3 splashes out of his 10 stories received the full page treatment. “Bullet-Proof Bad Man” provides a typical Kirby dramatic shoot out. Well not so much as gun fight as one man has only drawn his knife although it turns out this is not as unwise as it seems. It is clear that the bullet has found its mark but note how Jack seems to downplay the actual hit. The story is about a gunfighter that uses a special vest to protect himself from bullets. However I have notice that Jack seems averse to showing the actually striking of a bullet even though that is a moment he often depicts. Generally Kirby hides the action in a cloud of gun smoke. When, because of layout, that is not possible, such as above, Kirby will simply not include any impact lines.

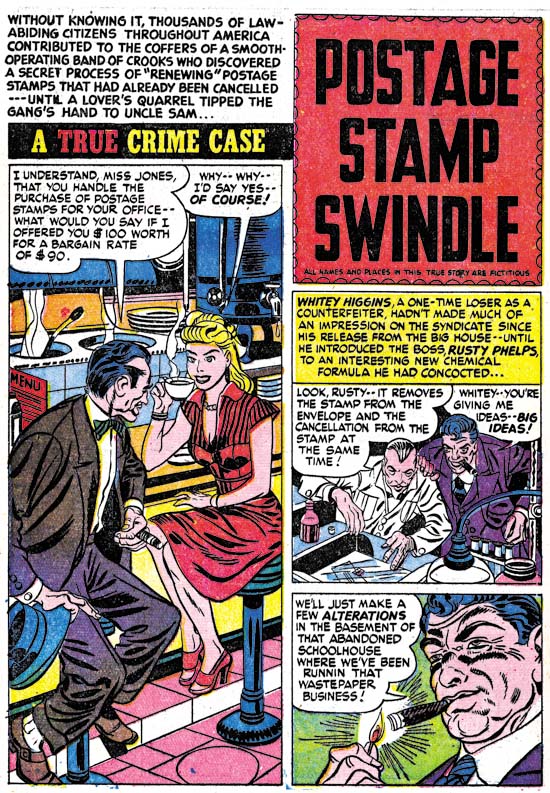

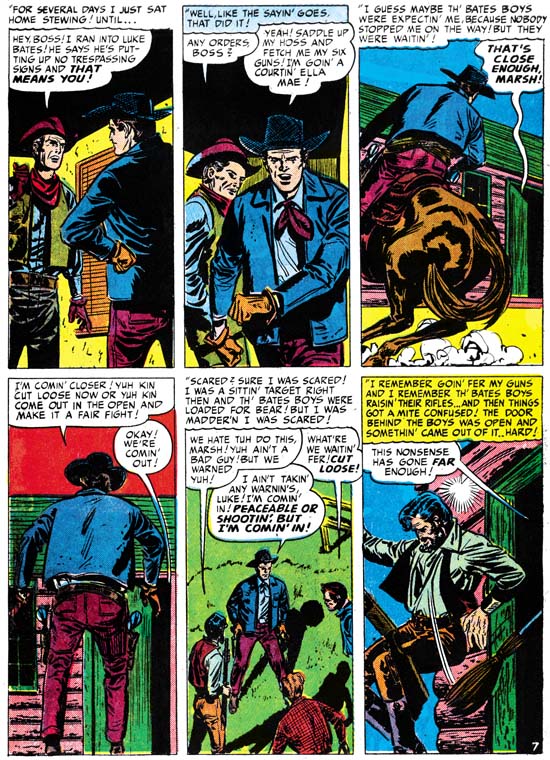

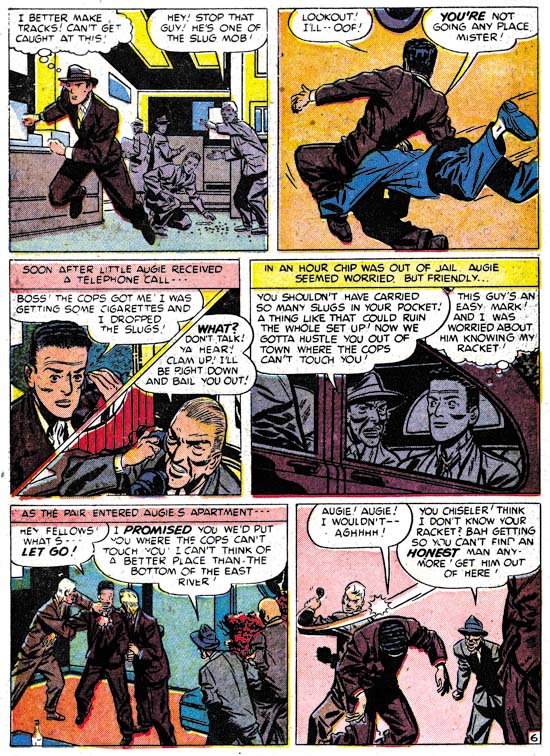

Justice Traps the Guilty #5 (July 1948) “A Fortune in Slugs” page 6, art by Bill Draut

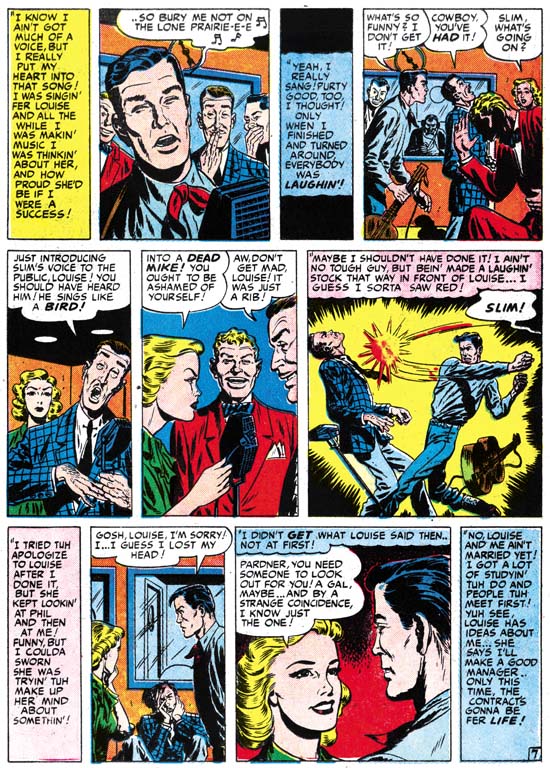

Bill Draut did so much romance work for Simon and Kirby that it is nice to see his efforts for the crime genre. These comics gave Bill a chance to provide more action then he would normally use in romance comics. Draut was better at adding excitement then would be expected based on his work towards the end of his career. Here on one page we find a man running, being tackled and in the final panel bludgeoned with a blackjack. All of which Bill handled quite nicely. I particularly like his use of perspective in the second panel. Draut shows the tackler flying into the page whereas Kirby would have had the action coming out toward the reader, but otherwise it was well handled.

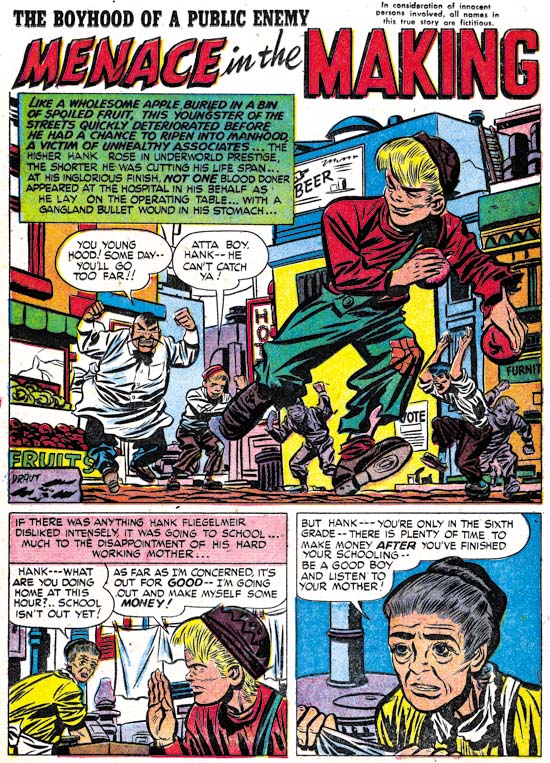

Headline #30 (June 1948) “Menace in the Making”, art by Bill Draut

Draut’s effective use of perspective is seen again in the splash for “Menace in the Making”. The low viewing angle allows the running figure to tower over all others without seeming to be unnatural. Action was not, however, the only outlet that Bill found in the crime genre. Crime stories allowed Draut to work, to extent that romance did not, in a more cartoony style. Note the caricature that Bill has provided the irate grocery man. Such interesting but fundamentally unrealistic depictions are found often in Bill Draut’s work in Headline and Justice Traps the Guilty but rarely in Young Romance or Young Love.

Justice Traps the Guilty #3 (March 1948) “My Strangest Crime Case”, art by Bill Draut

One story drawn by Bill Draut may not be exception as far as the art is concerned, but it is unusual in that the protagonist was a female private investigator. The story reads more like something from the hero genre then a true crime story. This is not the first time that Draut drew a story about a lady detective. In 1946 Draut worked on a feature called Calamity Jane originally for Boy Explorers Comics but when that title quickly failed (due to the comic glut after the war) subsequently published in Green Hornet Comics. It is likely that “My Strangest Crime Case” was left over material from that earlier effort that, with minor revisions such as to the detective’s name, was now put to use. The art style does seem to be a better match to Draut’s earlier work then to what he was doing at this time.

Headline #29 (April 1948) “The Night of the Freak Murder”, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

The team of Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin continue to appear in the crime issues covered by this chapter. The work is unsigned but the similarities to the signed works by Robinson and Meskin are numerous. “The Night of the Freak Murder” is unusual for Jerry and Mort in that it has a full page splash. Generally R&M’s splashes for Simon and Kirby productions are vertical with two story panels also arranged vertically. The composition is interesting in the way it plays off the grieving women with an almost mirror image of two detectives discussing the crime. The staircase might seem odd but it was introduced as part of a pattern that confines the eye in a circular composition. None of the other splashes that Robinson and Meskin supplied to Simon and Kirby were so well composed but as I said they did not normally use a full page splash.

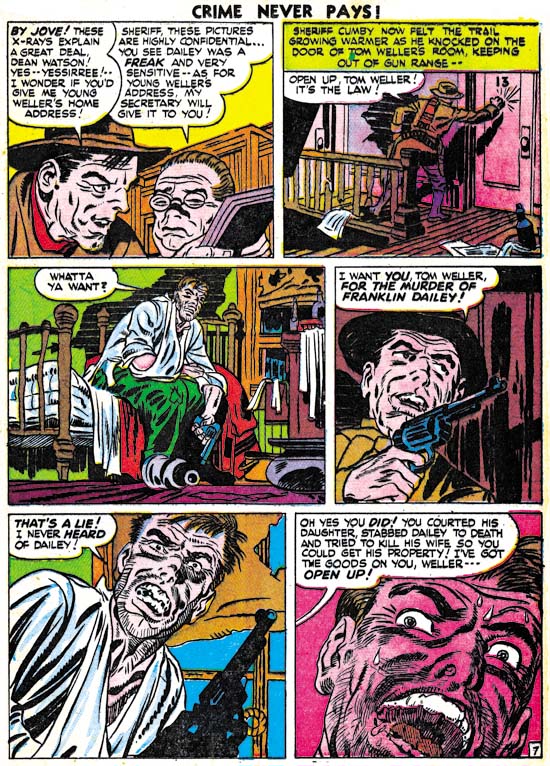

Headline #29 (April 1948) “The Night of the Freak Murder” page 7, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

As I mentioned in the previous chapter, I am not sure what Jerry Robinson’s contribution was because both the pencils and the art look very much like Meskin’s work. Mort was one of the best graphic story tellers and pages like the one above suggest why he had such an impact on artists like Steve Ditko. Here on this page the same diagonal is present in every panel. The page starts with close-up then switches to a distant show and then progressively comes closer. An increasing tension is formed by the combination of increased nearness, the diagonal design and off course the fear Meskin imparts to the criminal. Nothing really happens but the page is explosive nonetheless.

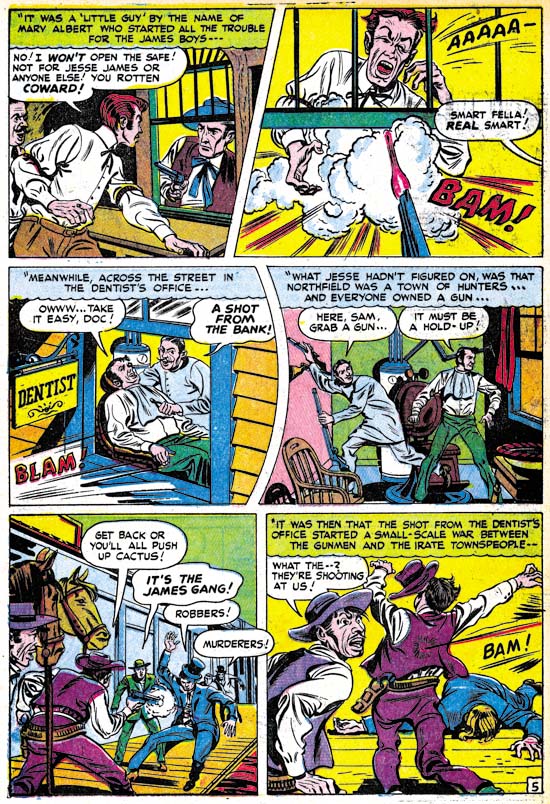

Justice Traps the Guilty #4 (May 1948) “Guilty Boys”, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

Not all of Robinson and Meskin’s splashes were vertically oriented; here is another case where they deviated from that pattern. This is a standard two thirds splash page with two story panels arrayed on the bottom. Nothing unusual in the design itself but it does allow Jerry and Mort to provide a memorable splash. Although the image seems cluttered, everything serves a purpose. Debris and damaged items abound and a row of buildings in the background all combine to show that this is a location in some slum. But the shabbily dressed musical boys are not the Newsboy Legion and this is not Suicide Slums. Here Robinson and Meskin convert the boy gang genre into crime. They are not saints and in the end are more in need of rescue then providing it.

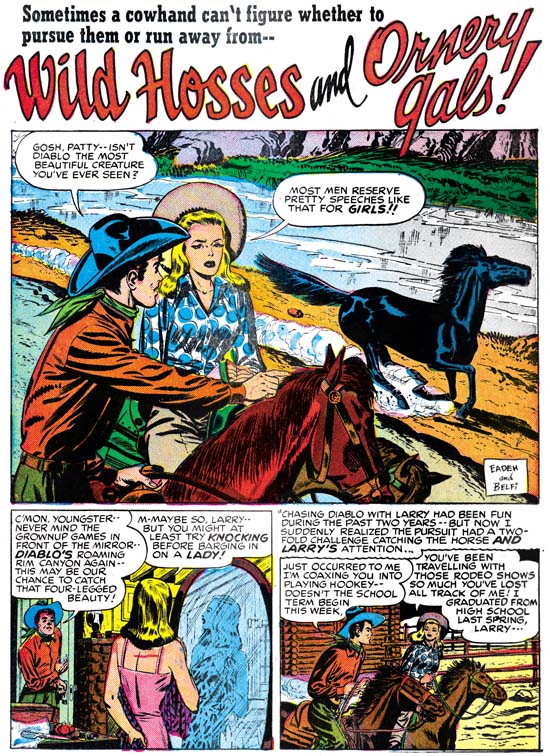

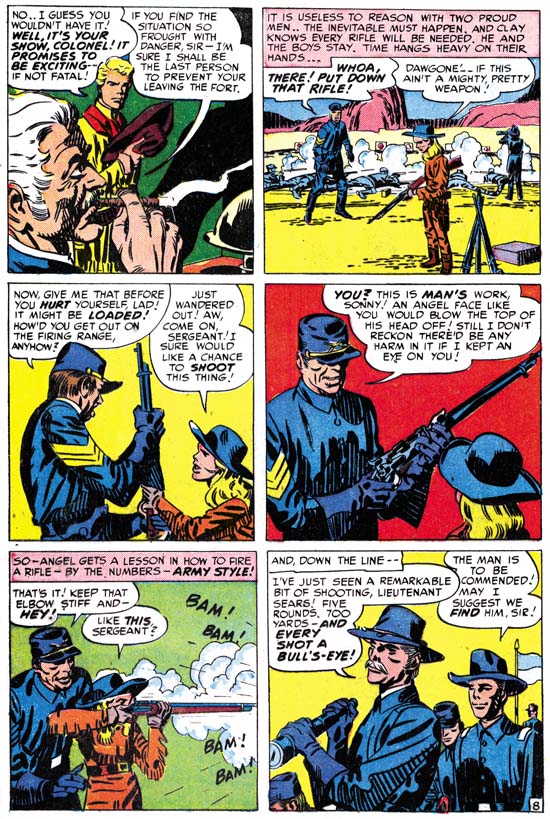

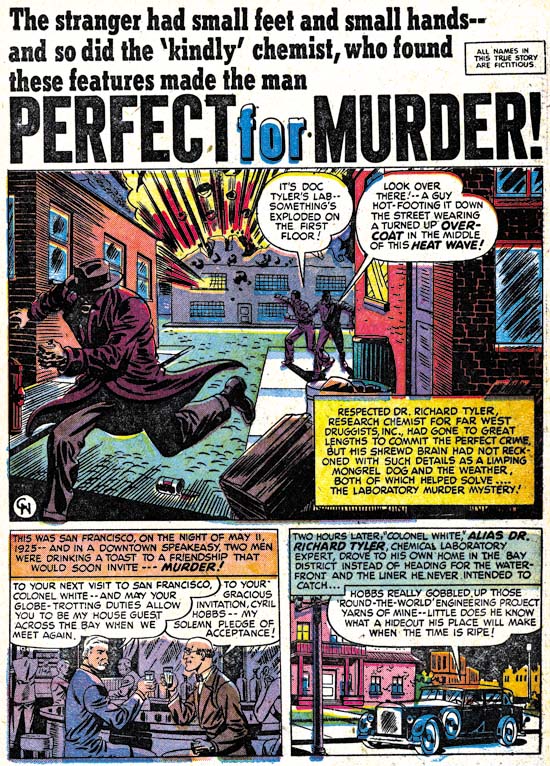

Headline #31 (August 1948) “Perfect for Murder”, art by Charles Nicholas

Only initials were used to sign “Perfect for Murder” (Headline #31, August 1948) but I am pretty certain it was Charles Nicholas. Originally Charles Nicholas was a house name used by Fox Comics for Blue Beetle stories. Over the years the work of many different artists appeared under that name, including Jack Kirby. However there were two individuals who continued to use the name outside of Fox and who claimed to be the creator of the Blue Beetle; Charles Wotjkowski and Chuck Cuidera. There is nothing I can add to that particular question here but it was the Wotjkowski version of Charles Nicholas who worked for Simon and Kirby at this time.

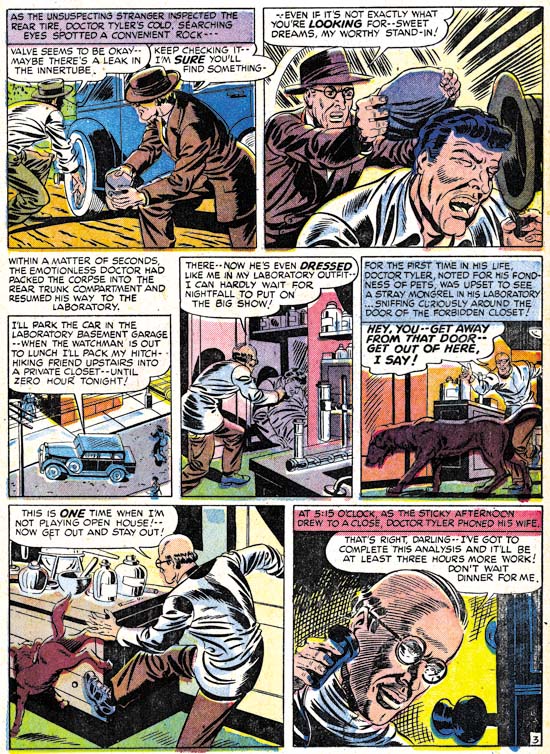

Headline #31 (August 1948) “Perfect for Murder” page 3, art by Charles Nicholas

While interesting, the splash page does not present a very good idea of Nicholas’ art so I have included an image of a story page as well. Nicholas does a good job drawing this story but he never achieved great success in his career as a comic book artist. Nicholas inked the art in a very individualistic style, as particularly seen in the form lines used in panels 6 and 7 and the swirling crosshatching in panel 7. (See my Inking Glossary for an explanation of my terms.) What is not found are any traits of the Studio style inking. While Nicholas is certainly a candidate for being one of Jack Kirby’s inkers, it is hard to understand how his name has become associated to the inking of particular pieces such as “Summer Song” (Young Romance #1, September 1947). “Perfect for Murder” was the only worked for Simon and Kirby signed or initialed by Charles Nicholas but other unsigned art by him surely remains to be identified.

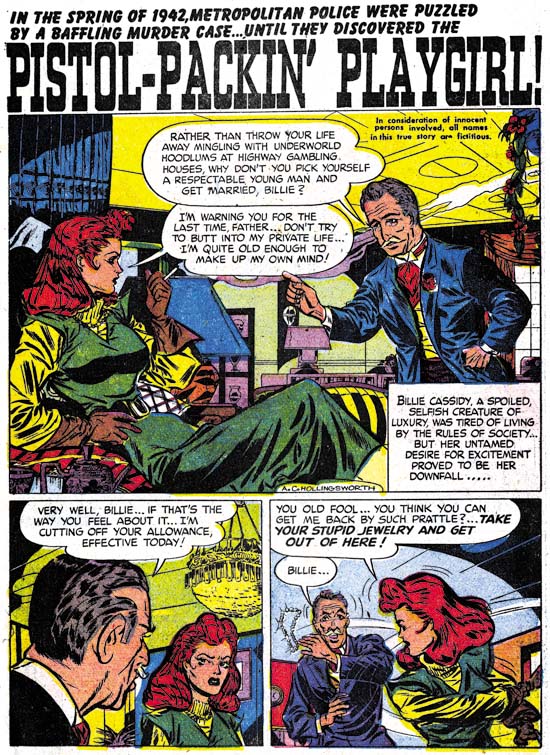

Headline #30 (June 1948) “Pistol-Packin’ Playgirl”, art by Alvin C. Hollingsworth

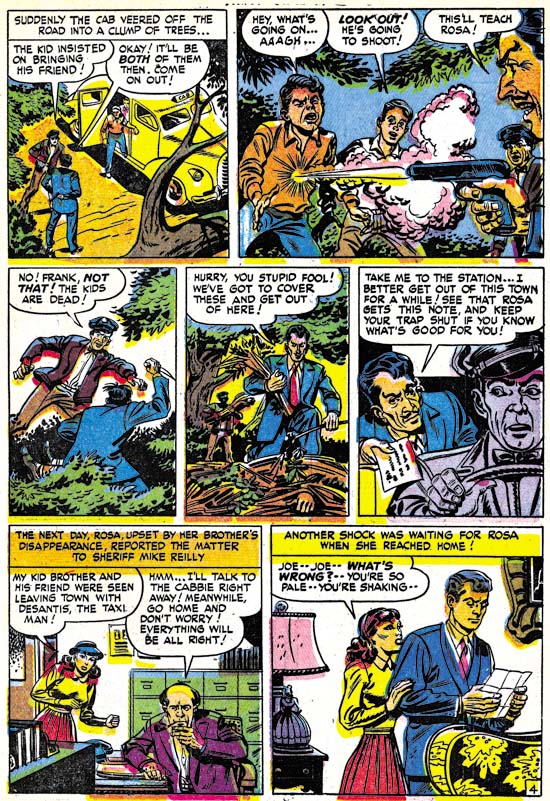

Another artist that shows up working for Simon and Kirby during this period is Alvin Carl Hollingsworth. A search of the Internet indicates that Hollingsworth was an African-American artist from New York who was born in 1928 and died in 2000. Previously he worked for Holyoke Publishing Company working on Catman. Hollingsworth was also a talented fine arts painter. Joe Simon remembers Alvin and has a high opinion of him. Joe remarked that he thought he was the only African-American working in comics at that time. This is not truly accurate since there was also Matt Baker who played an important part in the early history of comics. But Matt Baker never worked for Simon and Kirby and so Joe was not aware of him, or at least of his background.

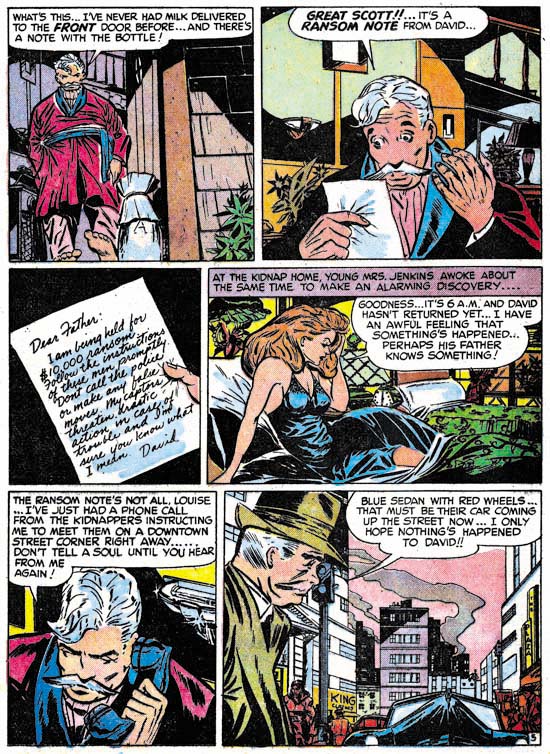

Justice Traps the Guilty #5 (July 1948) “Held For Ransom” page 5, art by Alvin C. Hollingsworth

Hollingsworth is another of those artists whose current reputation is much lower then warranted by his talent. This is largely because he left the comic book field in the late ’50s first for syndications strips and then the fine arts. It is a recurring pattern that I have noticed that comic book artists who did not take part in the superhero revival of the 60’s and later generally do not get much attention today. I have included a story page because it provides a better example of Alvin’s strengths. Note the use of varied and unusual viewing angles.

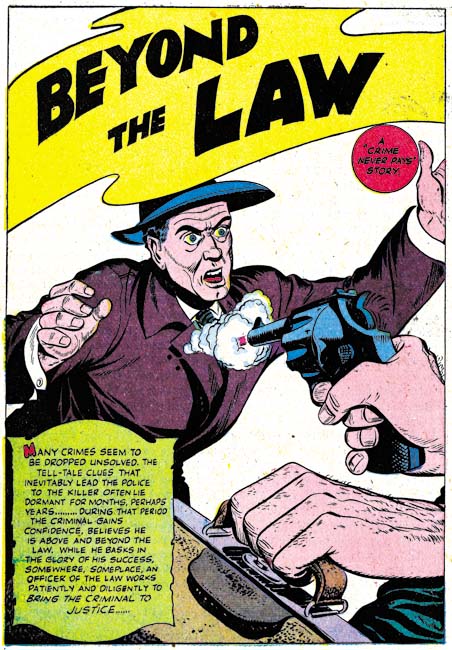

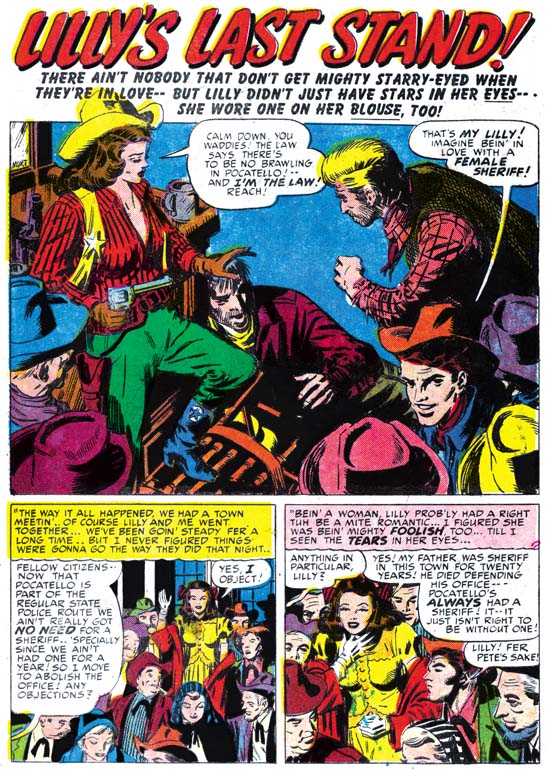

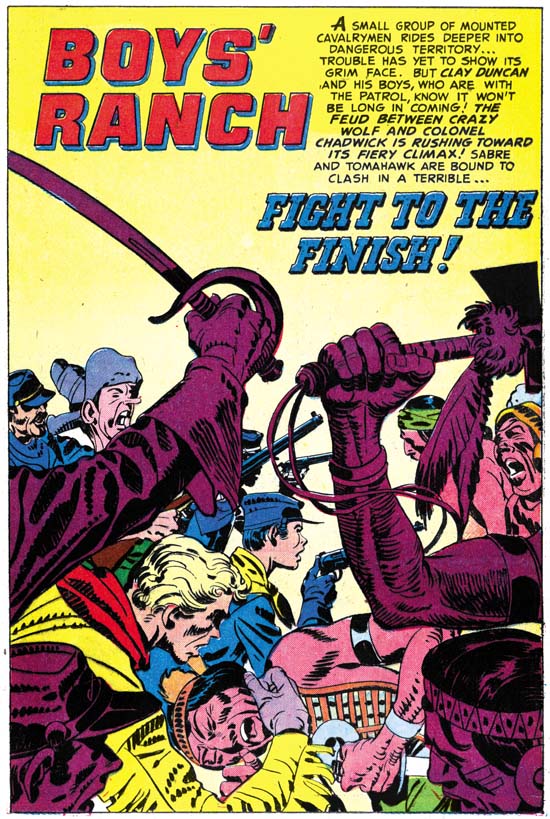

Headline #31 (August 1948) “A Gangster Dies”, art by Warren Broderick

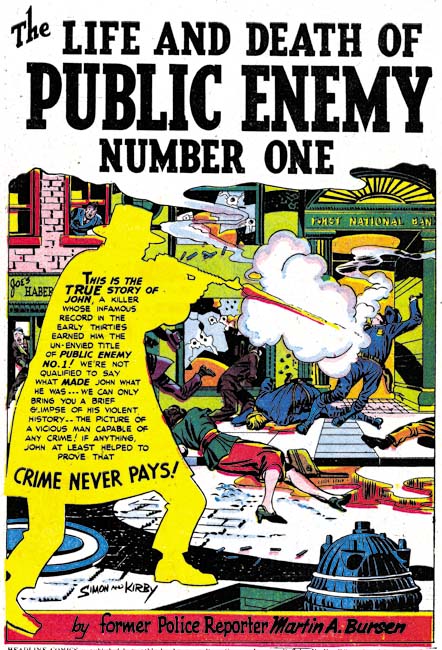

The Jack Kirby Checklist includes “A Gangster Dies” among the art works by Kirby. This is a bit surprising because close to the center of the splash page is Warren Broderick’s signature. Before I sound too self righteous I should add that when working on this chapter I found I had listed this story in my database twice; once as done by Broderick and the second crediting it to Kirby. I have no idea how I made the mistake in my database, but it is easy to understand why anyone who failed to notice the signature might attribute this work to Jack. Warren has obviously made a careful study of Jack’s work and has adopted, at least for his work for the S&K studio, much of Kirby’s style. Warren was not, of course, as successfully as Jack himself and there are more then enough clues to properly attribute his work even without a signature. Note for instance how in the splash Broderick uses picket fence crosshatching where the rails are cloth folds. Besides simple lines, Kirby would use drop strings and wide lines for the rails but I do not recall him ever using cloth folds. Kirby would often make expressive eyebrows but Broderick’s versions were even more exaggerated.

This is the only signed work by Warren Broderick that I have found among Simon and Kirby productions. Frankly I have forgotten about it until I reviewed for this chapter. It turns out that we have seen some of Warren’s unsigned work previously. In just the last chapter I attributed “The Killer Thought He Was Satan” (Justice Traps the Guilty #2, January 1948) as Kirby layouts finished by an unidentified artist. A comparison between it and “A Gangster Dies” leaves little doubt that it also was by Broderick. In fact I no longer believe Kirby laid it out. Yes there are parts in both stories that look very much like Kirby but there are also parts that do not. Previously I failed to follow my own advice and only noted the similarities and neglected the differences. For instance there is a panel I provided from “The Killer Thought He Was Satan” that showed a boy being shot by the villain. While the scene and the boy in particular look very much like it was done by Jack, the artist shows the bullet actually striking the boy. That is something I have yet to find Kirby doing.

Another example of Broderick’s work was “Mother Said No” (Young Romance #7, September 1948) seen in Chapter 3 of the Art of Romance. There I attributed the pencils to Jack Kirby (correctly) and the inks questionably to Carmine Infantino. The primary reason for my earlier caution was that I was bothered by Carmine’s statement in an interview that he had never inked Kirby’s pencils. While in the work for Charlie Chan, Infantino was also providing expressive eyebrows some of the other brushwork found in “Mother Said No” is more like that in Broderick’s work. Although Broderick was very good at mimicking Kirby, I find the layouts in “Mother Said No” are much too consistently like Jack’s that I still believe that Kirby did the pencils.

Headline #31 (August 1948) “A Gangster Dies” page 3, art by Warren Broderick

Broderick could mimic Kirby quite well but occasionally, such as in the first panel shown above, the similarity to Kirby’s style is very striking. This was either due to Kirby stepping in his roll as art editor and fixing up the finished art or it was the result of a careful swipe by Broderick from some Kirby art. Without the original art it is hard to be sure but I suspect the latter explanation to be the case. Once again Broderick has drawn a scene where a man is clearly hit by a bullet, something that Kirby would hide in a cloud of gun smoke.

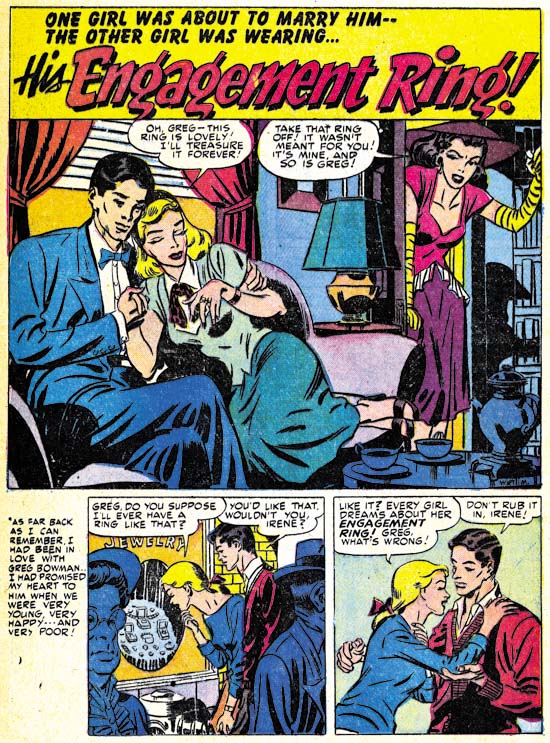

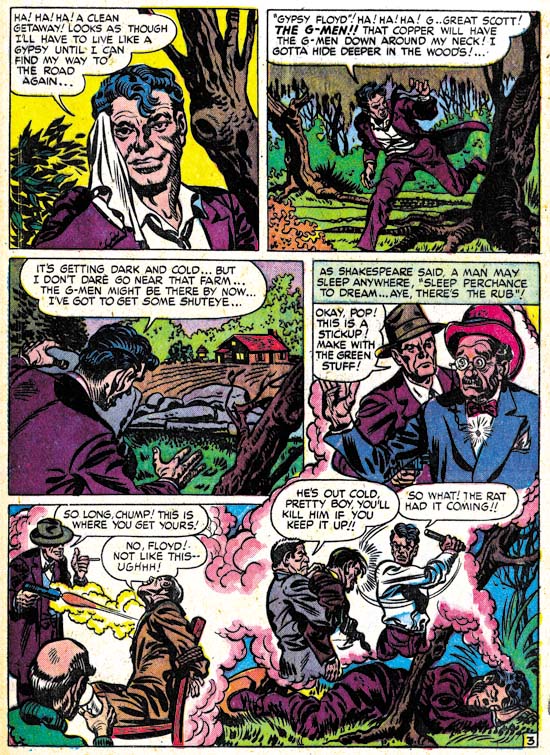

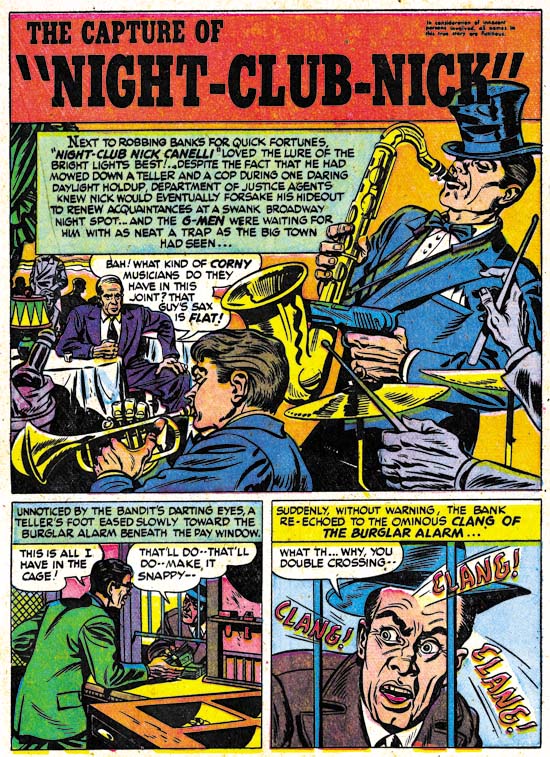

Justice Traps the Guilty #3 (March 1948) “The Capture of Night-Club Nick”, art by Warren Broderick

Broderick did not always so carefully mimic Jack Kirby’s style. In “The Capture of Night-Club Nick” Warren has abandoned the Studio style inking. Still the influence of Kirby is clearly discernable.

I have found little in my search for more information about Warren Broderick. I queried Joe Simon about him but he did not remember Warren at all. Joe does not remember all the artists who had worked for him over the many years, but in Broderick’s case this is surprising because the one thing I had found out was that he also was African-America. Joe was clear in his memory of A. C. Hollingsworth and that Hollingsworth was the only African-American to work for Simon and Kirby. How could Joe have failed to remember, even if not by name, one other African-American comic book artist? The answer maybe found in an interview given by comic artist, Harry Harrison:

After Wally and I broke up I was working mostly for Fawcett, and I had a friend by the name of Warren Broderick, who was also in school with me, doing my penciling. He was a black guy who didn’t want to get in there and push, didn’t want to face whitey in the office. We developed a nice clear style, no great shakes, but it worked.

This suggests that Broderick may have been reluctant to deal with Simon and Kirby directly and used someone, either an agent or another artist, as a go between. Joe may never have known about Warren’s ethnicity. The irony is that, considering their dealings with Hollingsworth, Joe and Jack probably would not have cared about Warren’s background, all that was important was that he could do the work.

The GCD only has three entries for pencils attributed to Broderick and three more for inking work. Atlas Tales has about a dozen works attributed to Warren. To that I can now add three further pencils and another inking job. Now that I have a small body of work to go by, I am sure I will find more work by Broderick as I continue to review Simon and Kirby productions. Warren Broderick is truly one of the forgotten comic book artists and it is rewarding to shed a little light on his career.

Chapter 1, Promoting Crime

Chapter 2, A Revitalized Title

Chapter 3, Competing Against Themselves

Chapter 4, Crime Gets Real

Chapter 5, Making a Commitment

Chapter 7, A Studio With Many Artists

Chapter 8, The Chinese Detective

Chapter 9, Not The Same

Chapter 10, The Master and His Protege

Chapter 11, The New Team