(July – December 1959: Young Romance #101 – #103, All For Love #15 – #17, Personal Love #12 – #14)

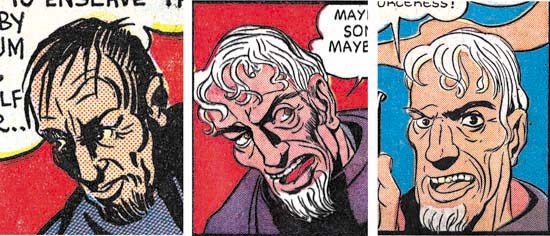

Young Romance #102 (October 1959) “The Wounded Party”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby was comparatively busy with romance art during this period providing one cover and four stories. All really nice pieces and all but one of them inked by Kirby himself. I do not think realism was ever an appropriate description of Kirby’s art, but his work seems especially abstract during this period. Note the simplified nostrils of both the man and the woman. The bridge of the nose seems unnatural. Details such as the eyelids are often dropped. But while these are by no means realistic portrayals, they are by no means unexpressive.

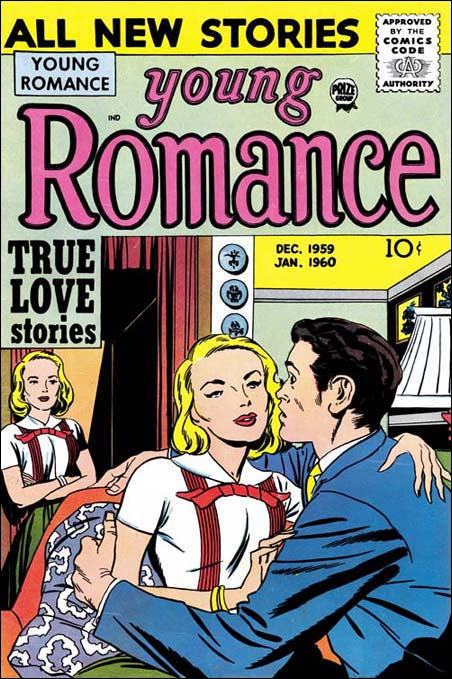

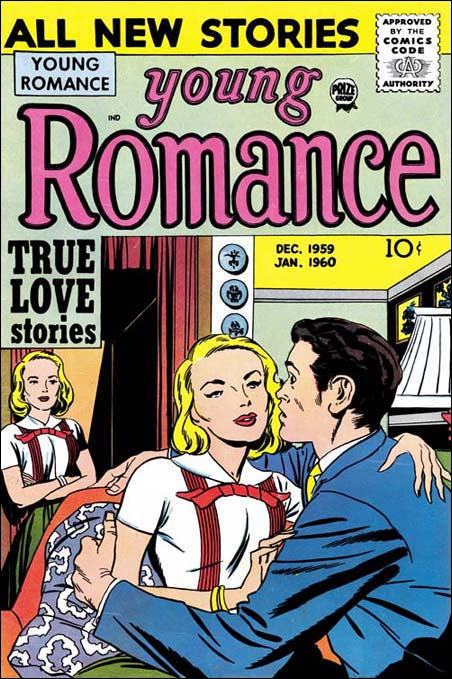

Young Romance #103 (December 1959), pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Kirby’s last cover for Young Romance, or any Prize publication. Jack presents a nicely humorous variation on the theme of a third party looking at a romantic couple.

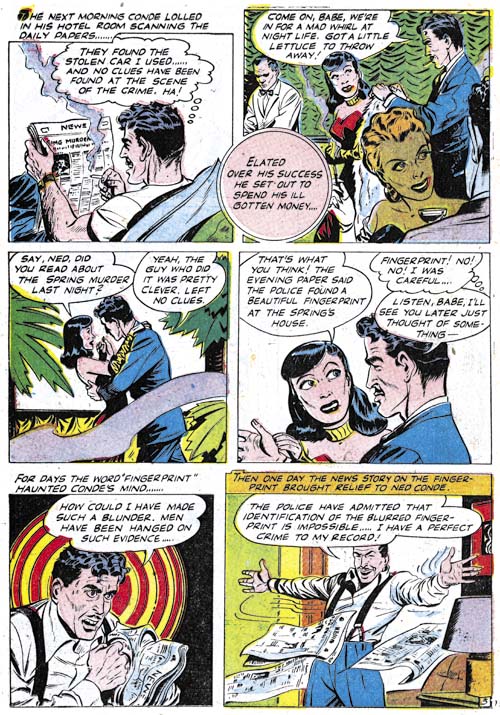

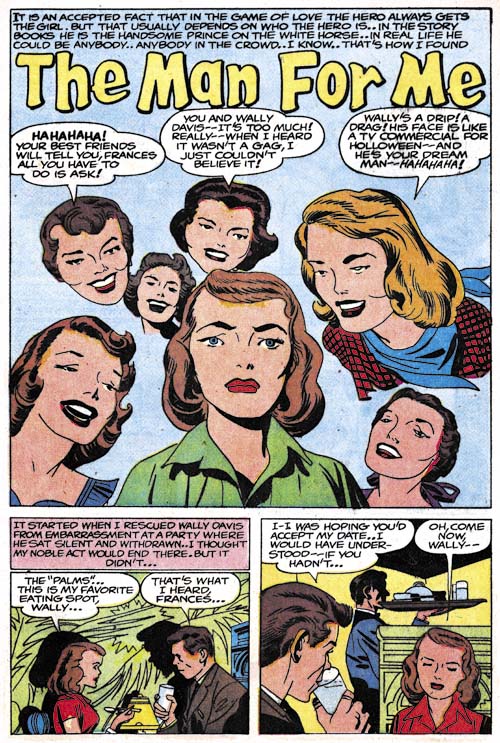

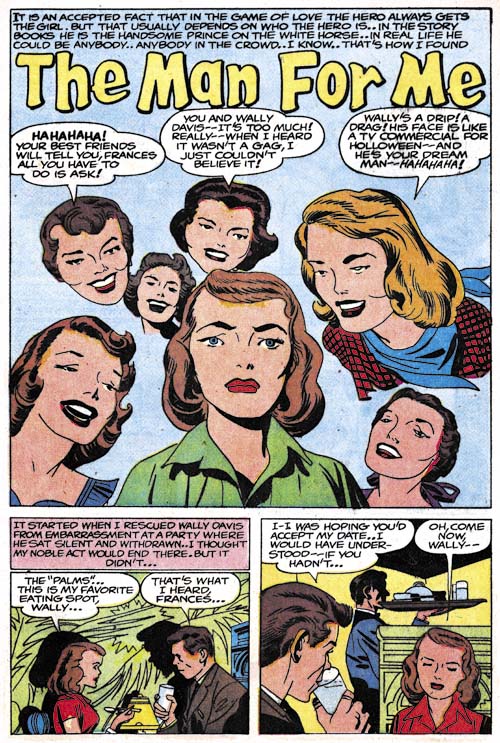

Young Romance #103 (December 1959) “The Man For Me”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Floating heads are not typical for Kirby’s art, but he does turn to them every once in a while. In this case it provides good examples of how Kirby was now drawing woman. In this respect his art is at a mid-point. Earlier Jack drew woman with much variation in looks, some of which while not completely unattractive would hardly be described as beauty queens. Later in his career, most of Kirby’s woman looked alike; differing mainly in their hair and clothes styles. In the splash for “The Man For Me” there still is some variation in the faces of the woman but nowhere near as much as before. All are attractive but I wonder if many readers in 1959 would have consider these woman as truly beautiful?

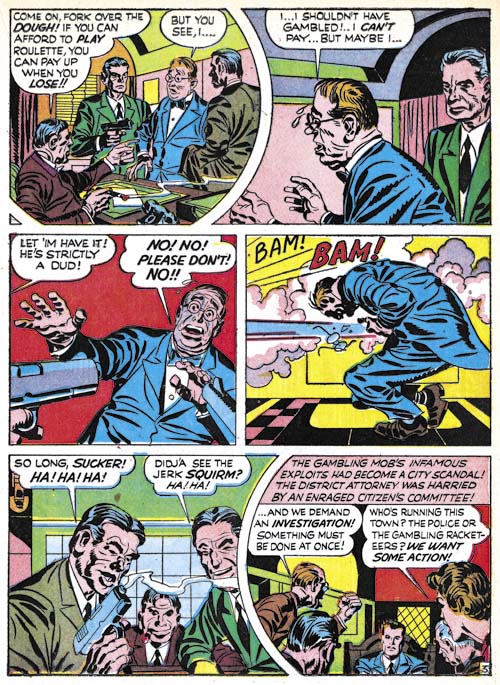

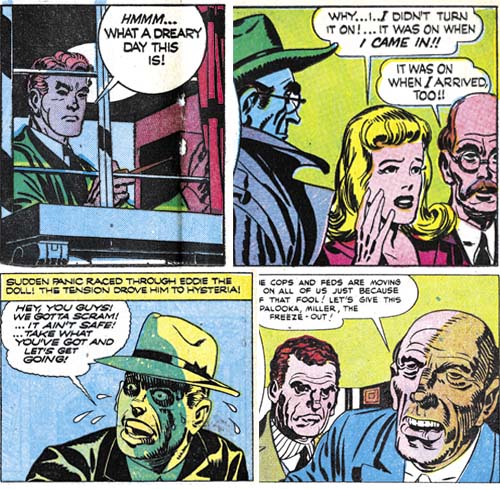

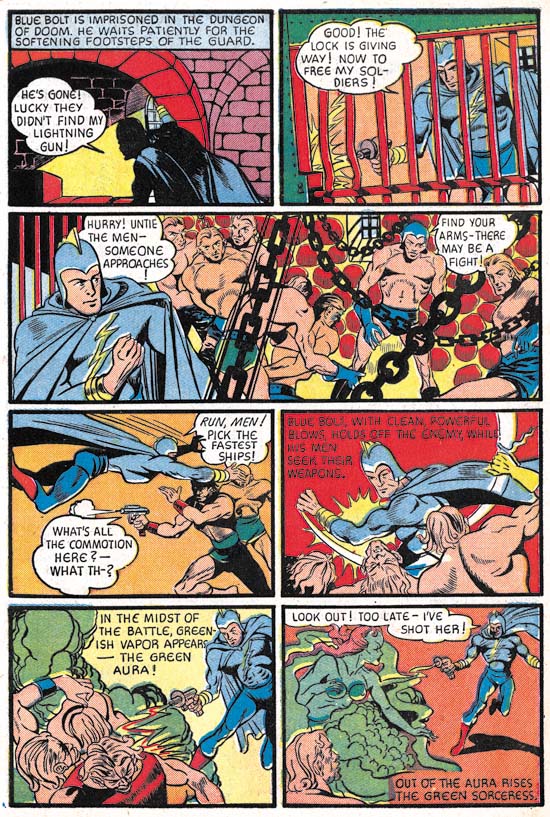

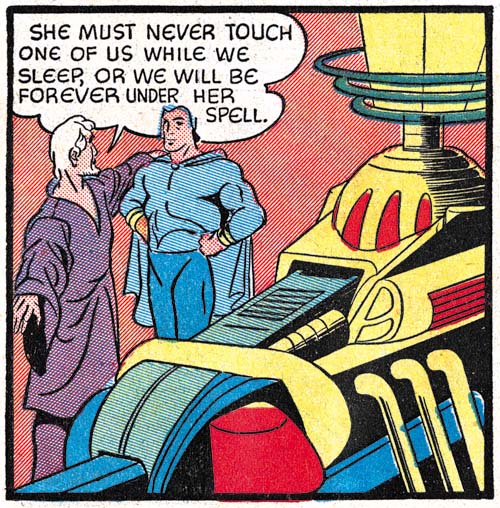

Young Romance #103 (December 1959) “Liars In Love” page 4, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

A final example of Kirby’s romance graphic story telling. Shifting perspective, varying viewing distances, body language and facial expressions all played a part in Jack’s art. What a master.

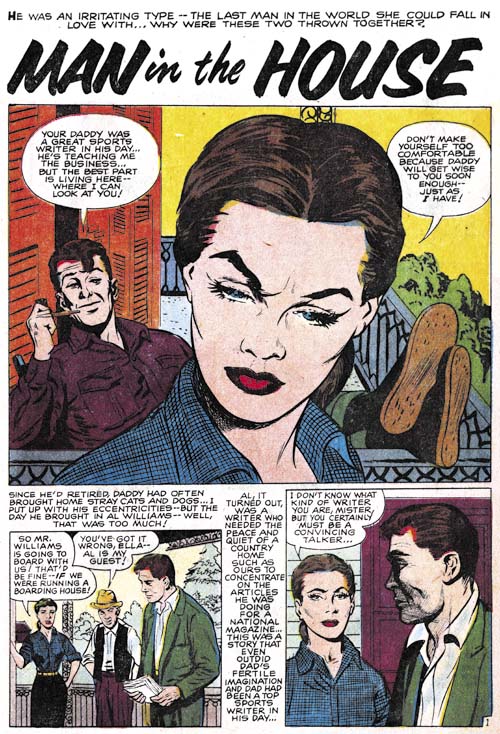

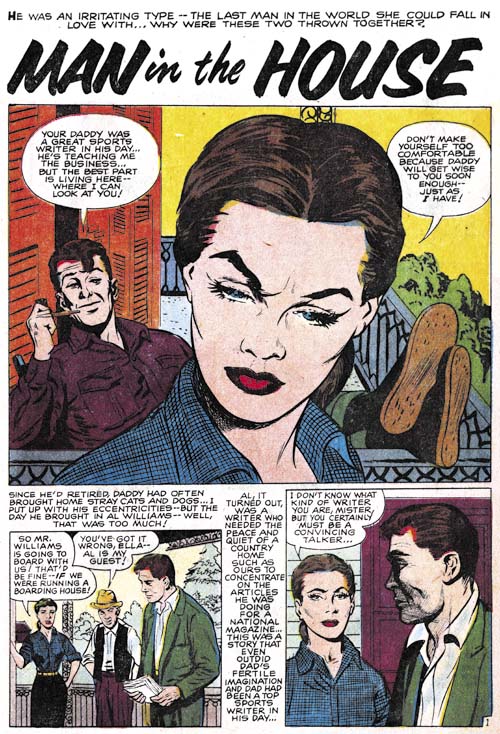

Young Romance #101 (August 1959) “Man In The House”, pencils by John Prentice, inks by Joe Simon

In the last chapter I briefly discussed a piece that looked like the work of John Prentice. The problem was that it was not nearly as well done as was typical for Prentice. I put off deciding about the attribution until this chapter where I would have four stories by the same artist to examine. While it is perfectly possible for one artist to imitate another, it is difficult if not impossible for such imitation to be consistent over an entire story, let alone a number of stories. This work must have been drawn by John Prentice. But there are some parts that look like some other artist hand, in fact like a particular artist, Joe Simon. I now believe that unlike his prior practice, Prentice only supplied pencils which Simon then inked. I have to say that as much as I admire Joe as an artist he really was not doing Prentice justice. Perhaps it was Joe’s blunt brush, which had gotten even blunter over the years. Perhaps Joe was in a rush.

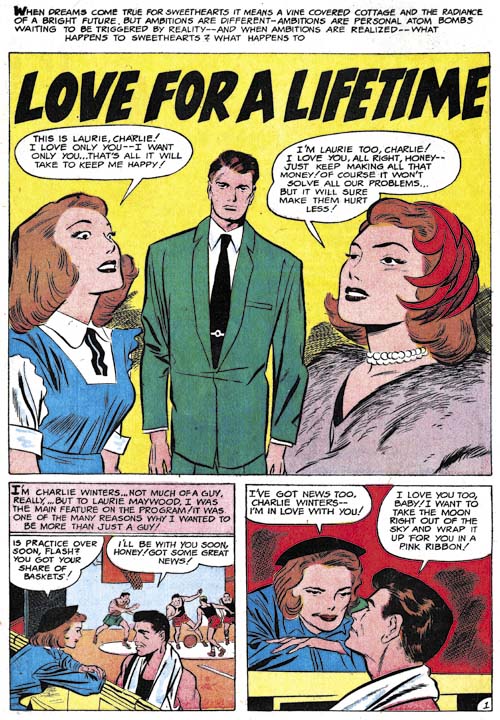

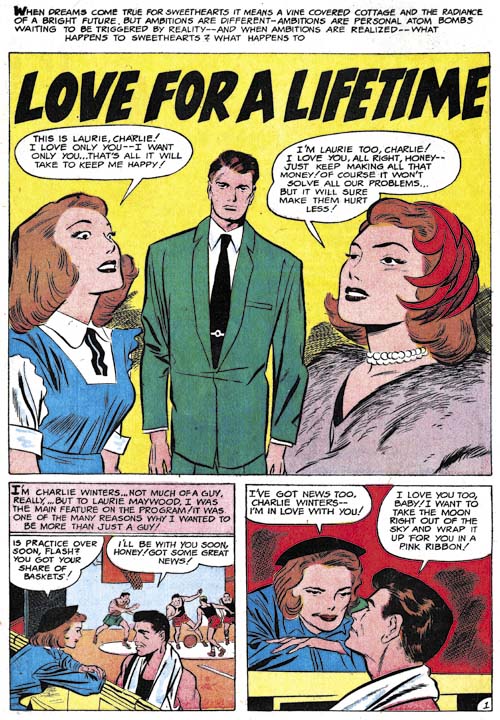

All For Love #15 (August 1959) “Love For a Lifetime”, pencils by Jack Kirby

During the prior year and a half, Kirby only appeared in Young Romance. “Love for a Lifetime” is the first, and only, piece Jack did for All For Love. This was not the only example of an artist that appeared in Young Romance and either All For Love or Personal Love. I will be pointing out some other below and conclude with an explanation why this was happening. Kirby did not ink “Love for a Lifetime”. Nor was it inked by the artist who Jack used often at this time for his inking (who I believe was Marvin Stein). The inker did a good job but I have no idea who he was. This seems to be the only piece he inked for Kirby.

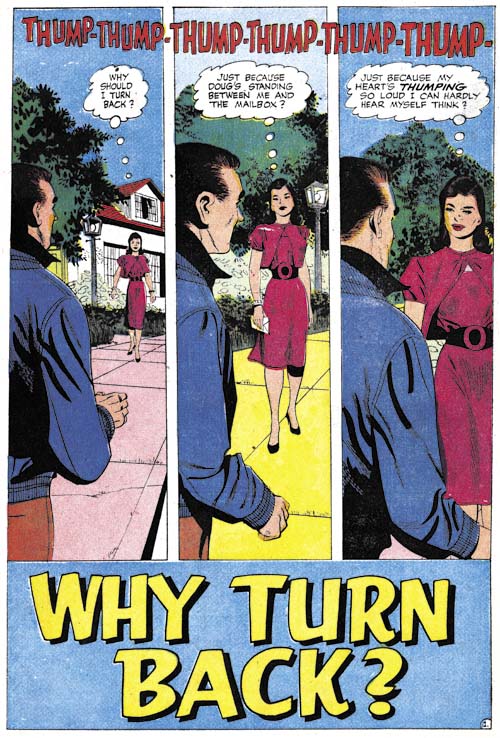

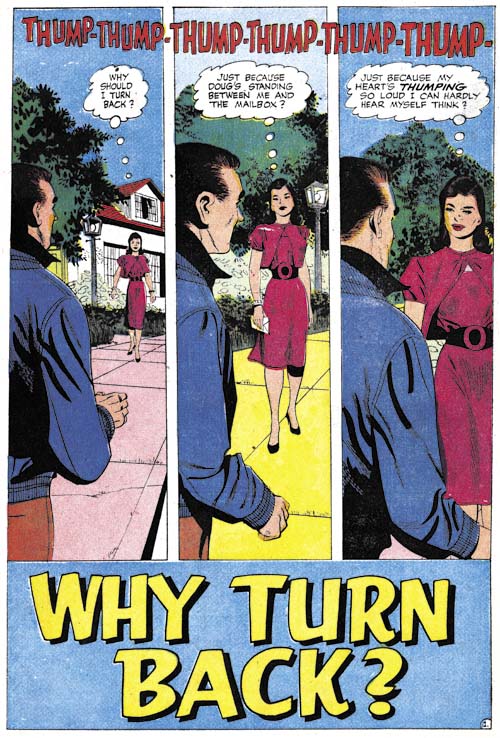

All For Love #17 (December 1959) “Why Turn Back”, art by Paul Reinman

Previously Paul Reinman was another artist who frequented Young Romance but never appeared in either All For Love or Personal Love. During the period covered in this chapter, Reinman drew four stories but only one appeared in Young Romance. The others were published in All For Love.

The piece I selected as an example of Paul’s work is perhaps not the most typical of his art. But I find the art for the opening page rather nice. The tall narrow panels and the way the lady advances in each panel is very interesting. There is something a little unnatural about it all but it is still very effective.

All For Love #15 (August 1959) “Scheduled For Heartbreak”, art by Bob Powell

A new artist appearing in the Prize romance, or more correctly reappearing in the case of Young Romance, is Bob Powell. Powell did five stories; two for Young Romance, two for All For Love and the last for Personal Love. Hence is another example of an artist during this period appearing in all the Prize romance comics. Powell used studio assistants and his art varied quite a bit. I believe Bob had little if anything to do with some of the work attributed to him for the Harvey romance titles. Quality of the Prize romances vary but in my opinion all had significant involvement by Powell himself.

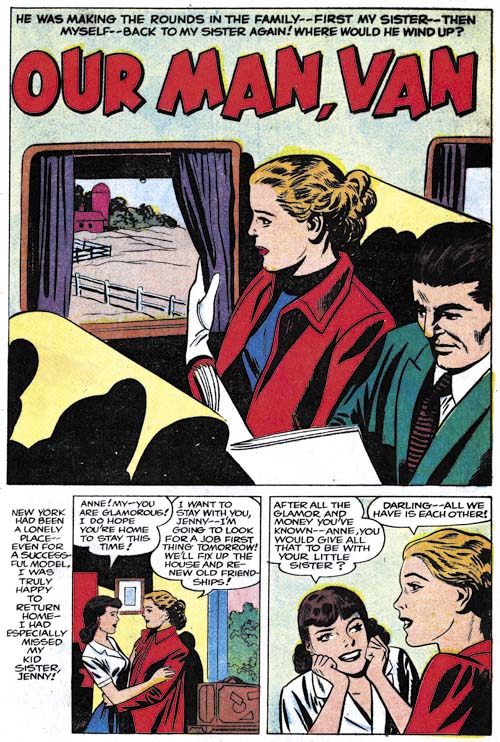

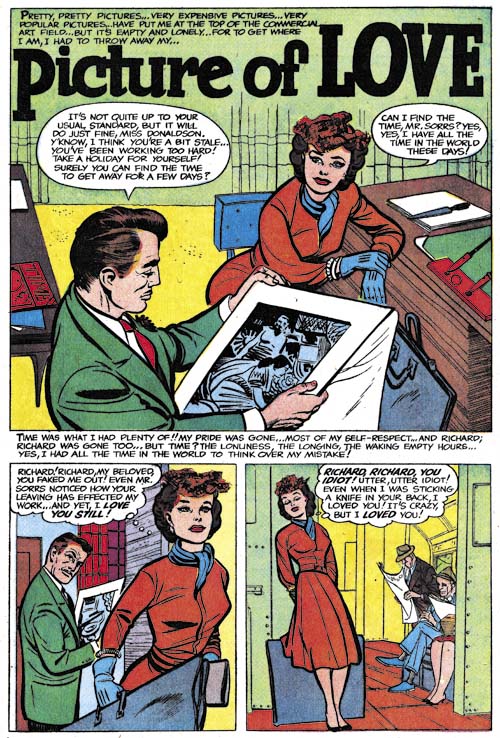

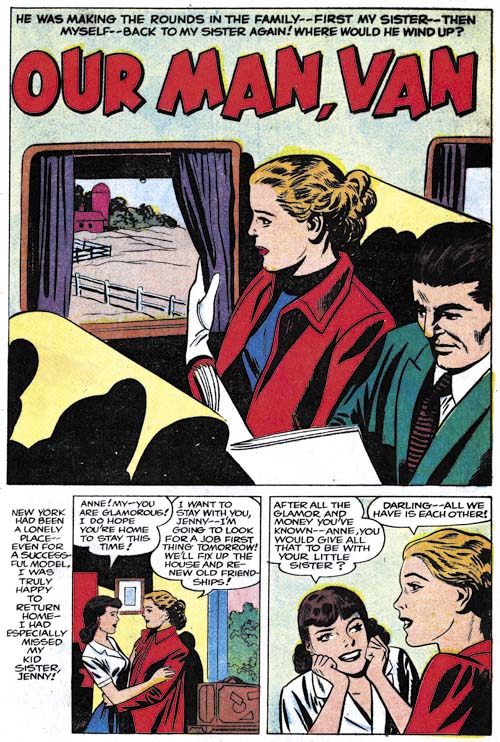

All For Love #17 (December 1959) “Our Man, Van”, pencils by Bruno Premiani, inks by Joe Simon

Perhaps my biggest surprise when reviewing this period was return the of Bruno Premiani. Premiani last worked for Simon and Kirby from in 1949 and 1950. He is said to have left the United States in 1952 (in a short biography by an unknown author which no longer resides on the web) but returned in 1960. However “Our Man, Van” indicates Bruno was actually back in the U.S. around July 1959 (the proper date for creation of art with a December cover date).

Premiani, just like John Prentice, provided pencils only Which Joe Simon then inked. Again it was not the best combination. Further Bruno only did this one story (probably because he began working for the better paying DC).

I should add that earlier in this series I always included a question mark with my Premiani attributions. That was because the work for Prize looked different from what at that time I had seen by Premiani. Since then I have examined a story in DC’s Greatest Adventure that Bruno did that shows a similar drawing style. So I have now dropped off the question mark feeling confident that Premiani was indeed the correct attribution.

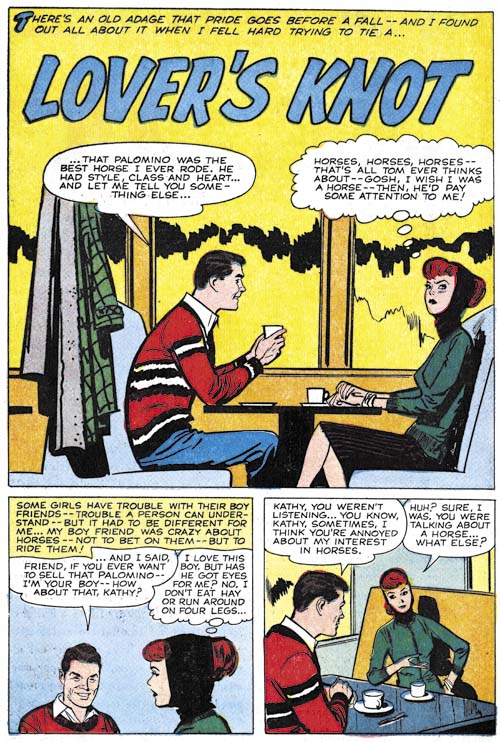

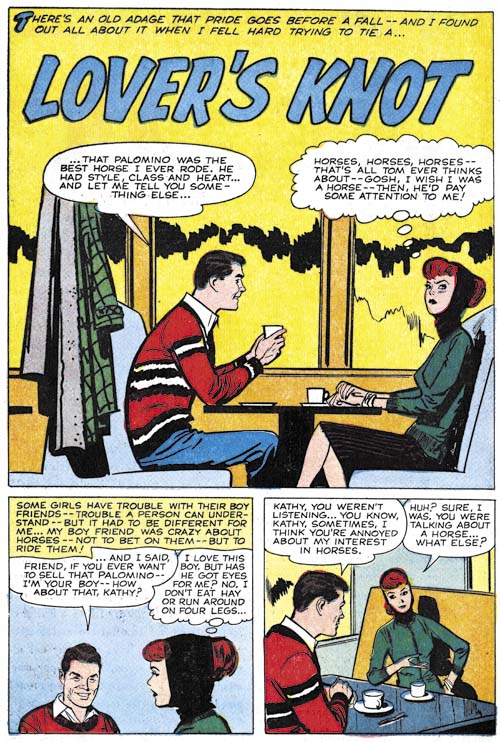

Personal Love #12 (July 1959) “Lover’s Knot”, pencils and inks by Marvin Stein

There is only a single piece during this period by Marvin Stein (same thing was reported in the last chapter). Marvin has gone further in simplifying his art. That is saying a lot since his earlier work would hardly be called complex. Stein has gone so far that I doubt I would have recognized his hand in this work had it not been for “Lost Paradise” (AFL #14, June 1959), the previous piece that he did. While his art style had changed he has not lost his skill at graphically telling a story. It would have been interesting to see where Stein’s style would end up had he continued to do comic book art but unfortunately I believe this he is last comic piece.

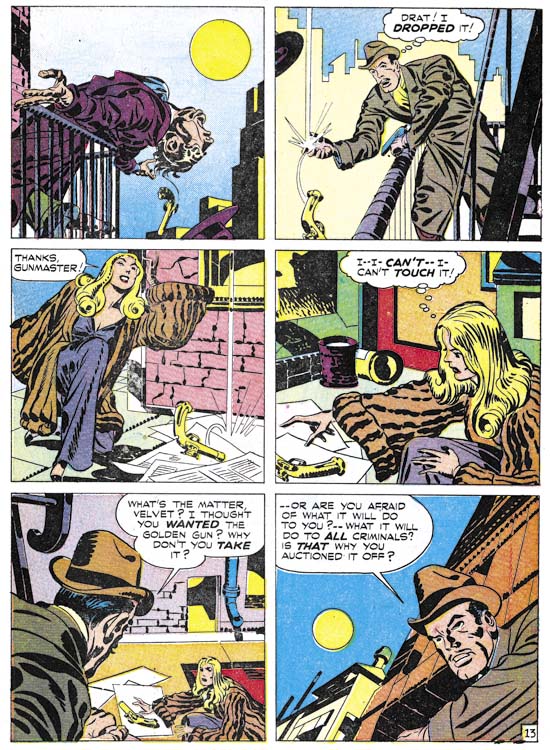

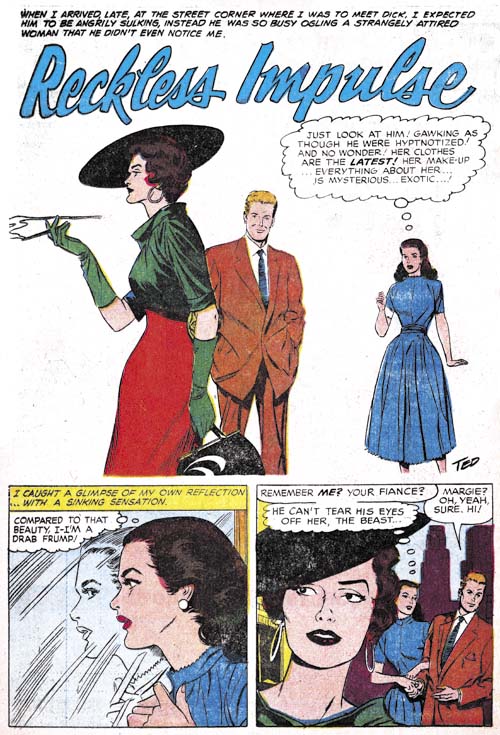

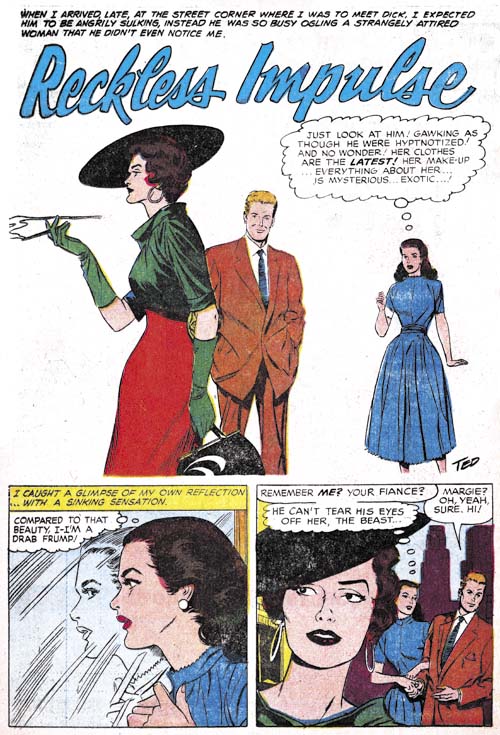

Personal Love #13 (September 1959) “Reckless Impulse”, art by Ted Galindo

While some artists were appearing in both Young Romance as well as All For Love or Personal Love, Ted Galindo was not one of them. All three stories that he did appeared in Personal Love. He really was a talented artist and among the Prize romance artists he seemed to be the one to experiment the most. For the “Reckless Impulse” splash, Ted has completely eliminated all the background as well as the panel border. The rest is very effective.

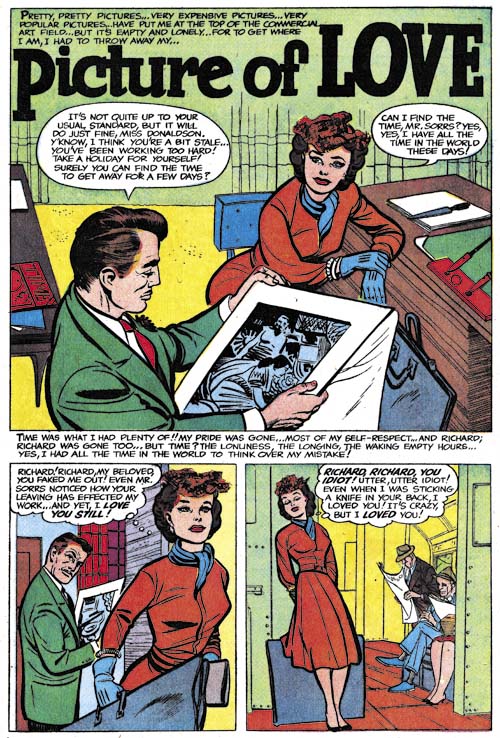

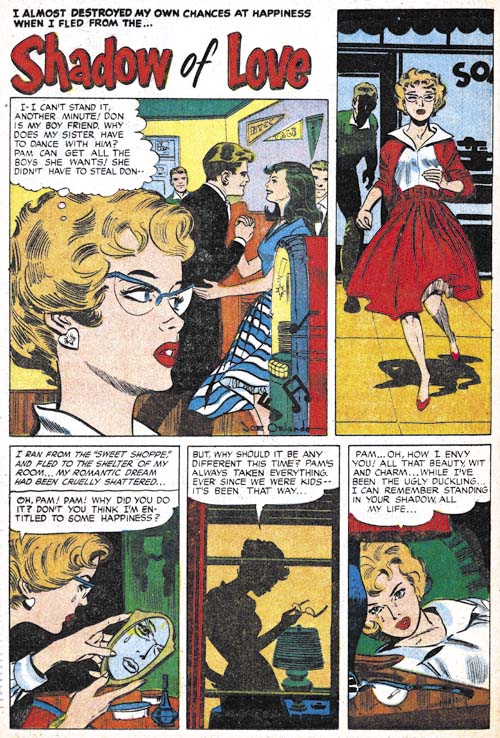

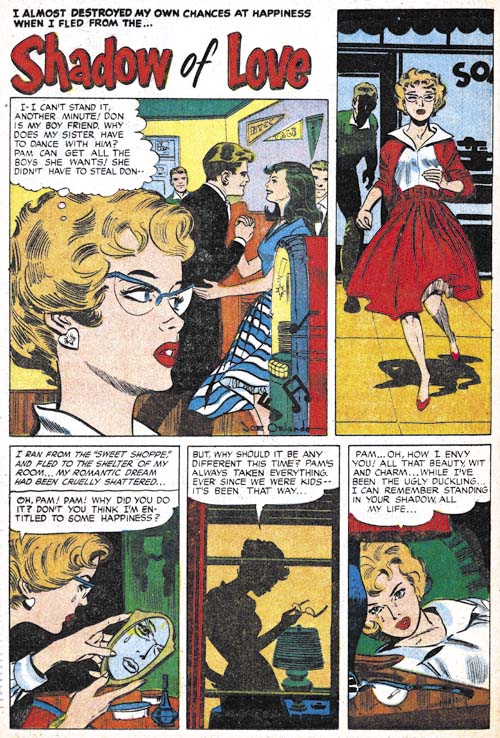

Personal Love #13 (September 1959) “Shadow of Love”, art by Joe Orlando

Yet another Orlando signature that I missed until this latest review. During this period Joe also did an unsigned piece. Orlando also seemed to like to experiment a little. The splash is actually part of the story but what is more interesting is that the second panel is higher than the splash. The three remaining panels are also tall and narrow.

Chapter Conclusion

In his book, The Comic Book Makers, Joe reports that when Mike Bleier (one of the partners for Prize Comics) died in 1960 the remaining partner, Teddy Epstein, asked Joe to take over the comics. So it is not surprising that the postal statements from 1960 until 1963 list Simon as the editor. In 1960 Joe would replace All For Love and Personal Love with a re-launched Young Love and a new title Going Steady. In the past I believed these steps were taken by Joe as soon as he began as the romance editor. This review has made me change my mind. During the previous year and a half the different artists appeared in Young Romance as compared to All For Love or Personal Love. Jack Kirby and Paul Reinman were only shown in Young Romance while Ted Galindo and Joe Orlando only worked for All For Love and Personal Love. Other artists, most unidentified, also followed this pattern. The only exception seems to have been Marvin Stein who appeared in all the Prize titles. However Jack Kirby is in the August issue of All For Love and Reinman does work for the December issue. John Prentice appears in YR #101, AFL #15, #16 and #17. Bob Powell shows up in YR #103, AFL #15 and #16, as well as PL #16. My conclusion is that Joe started as the romance editor in August when this mixing of artists began. This would mean that the 1960 date of Bleier’s death is inaccurate; that he actual died in 1959. I believe that such a error is understandable and not particularly significant.

Series Conclusion

When I started this serial post, Art of Romance, I knew it would take some time to finish. Well over two years later and with 38 chapters I have finally come to the end. Prize’s romance comics would continue from 1960 to 1963 but they were different from what came before. In his book, Joe described it as a basement operation with substantially reduced art and script costs. Most importantly for this blog, they would no longer include any involvement from Jack Kirby. In fact there would be no further Simon and Kirby collaboration of any type until many years later. I am certain I will post about the Prize romance titles under Joe Simon someday, but I am not prepared to do it now.

While for most fans, Simon and Kirby’s reputation rests on their superhero, crime, horror and similar genre, the romance genre was much more important to Joe and Jack. To put some perspective on it for the period spanned by this serial post (cover dates September 1947 to December 1959) Jack Kirby drew a total of 3855 pages of art*. At 1936 pages, romance was by far the greatest part of that work. The breakdown per genre is:

1936 romance

507 hero

459 crime

417 horror

356 western

91 humor

45 science fiction

24 war

20 anthology

There was more romance art than all the other genre combined. Once Simon and Kirby launched Young Romance, they never stop producing romance comics right up to their parting of ways at the end of 1959 (cover dates). Simon and Kirby produced no other genre continually during that period.

One of the themes of this blog is that Simon and Kirby did not only create art, they produced comics as well. Actually that is how they made most of their money. While working together, Simon and Kirby produced 7593 pages of romance art**. This included the work of a lot of different artists and since Simon and Kirby seem to encourage the creators to sign their work, this serial post was able to identify and give examples of the majority of the contributors.

I thought I was well acquainted with Simon and Kirby romance work when I started Art of Romance but I learned a lot by reviewing them sequentially. Much of the knowledge I gained concerned artist attributions but there was three more general observations as well.

Based on interviews of a couple writers that Simon and Kirby had employed, Jack was heavily involved in supplying the writers with plots. But in my opinion, Kirby subsequently had little if anything to do with the stories supplied to the other artists. However I believe something very different happened with the stories that Kirby drew himself. I find the writing of the Kirby drawn romances to be very different for the stories drawn by others. Frequently they display phrasing that to me sound very much the writing of Kirby himself. I am certain that Jack would re-write much of the scripts that he drew.

With the exception of Jack’s own art, Simon and Kirby left all inking of art to the artists themselves. That does not mean that all the other artists inked their own work but the great majority of them appeared to do so. Certain this was the case for frequent contributors Bill Draut and John Prentice. Mort Meskin’s pencils often inked his own pencils but he for a time he used George Roussos as an inker as well. I do not claim to have sorted it all out but my opinion is that Mort did almost all his own inking with a relatively small fraction inked by George. Inking of Kirby’s pencils was something very different. Joe Simon has described it as an assembly line with different inkers contributing to different parts of the same story. My observations of the actual comics supports Joe’s statements. When I identify a particular inker of Kirby’s art I am not saying that they were the only inker but rather just the only one I thought I could identify but other inkers may have been involved as well.

My final observation concerned the question of Kirby layouts for other artists; an often repeated claim. It is also one that is difficult to disprove by conventional comparisons. That is because it is hard to distinguish the difference between layouts, influence and swiping. Particularly since it often involves admittedly subjective criteria. The methodology I have found often useful was panel layouts. I would compare panel layouts from Kirby’s own work and those of other artists during the same period. After all its seems very unlikely that Kirby would adopt different panel layouts for work supplied to other artists to complete. I often found particular panel layout used by some artist over and over again. for instance during one period Leonard Starr frequently used tall narrow panels that rarely appeared in Kirby’s art. Using panel layouts I can confidently say that Kirby did not supply layouts to more important artists like Bill Draut, Mort Meskin, John Prentice, Bob McCarty and others. Kirby did appear to provide layouts for some minor and less talented artist but then the difficulty becomes distinguishing Kirby layouts that were finished and inked by the other artist from Kirby pencils just inked by another artist.

Footnotes:

* In the calculation present here I am excluding the work Kirby did for DC and Atlas after the breakup of the Simon and Kirby studio. I have included the 146 pages of Boy Commandos in the hero genre. Personally I do not consider the Boy commandos published during the time of World War II as war comics, but the post-war examples clearly do not belong in that genre.

** I am excluding from these calculations All For Love and Personal Love. As I discuss above Joe Simon may have been the editor of these titles as well for a period. However there is little reason to believe Jack Kirby had anything to do with them other than supplying a single story for All For Love.

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

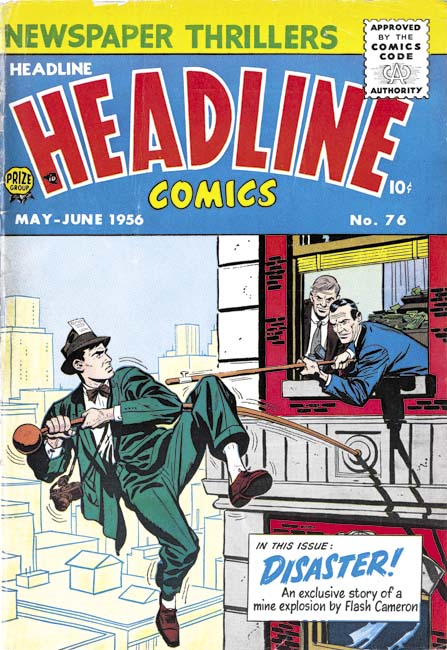

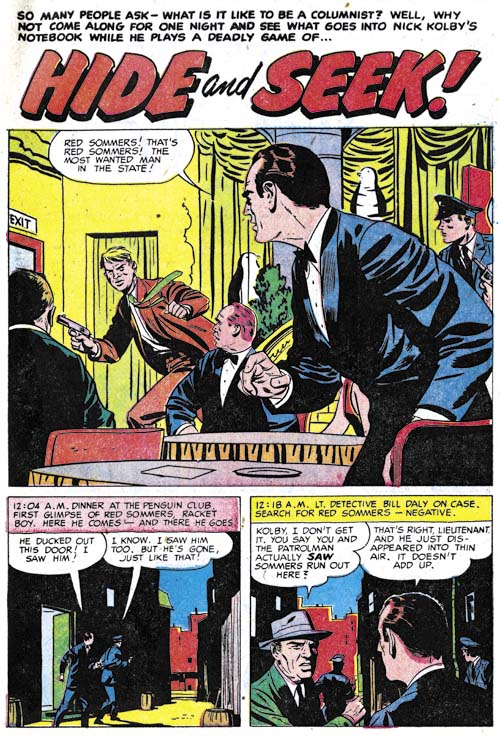

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)

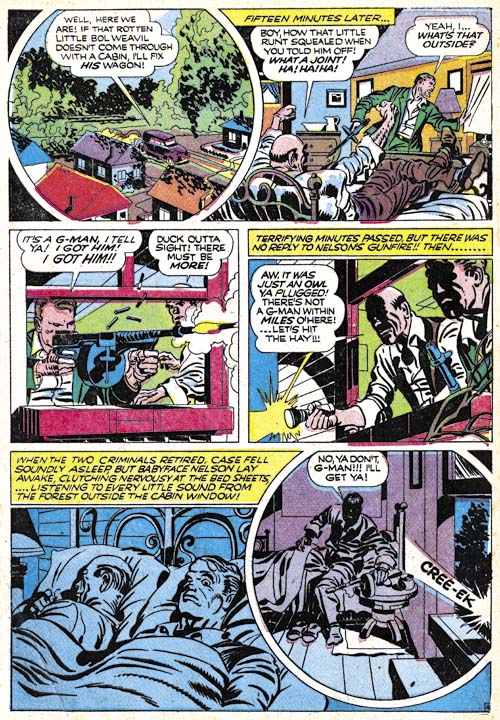

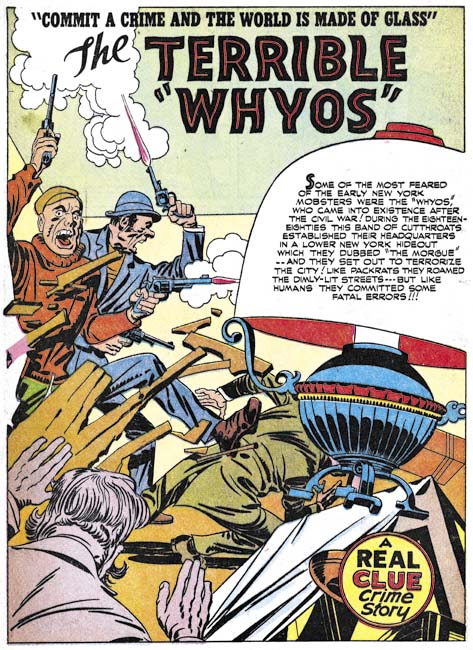

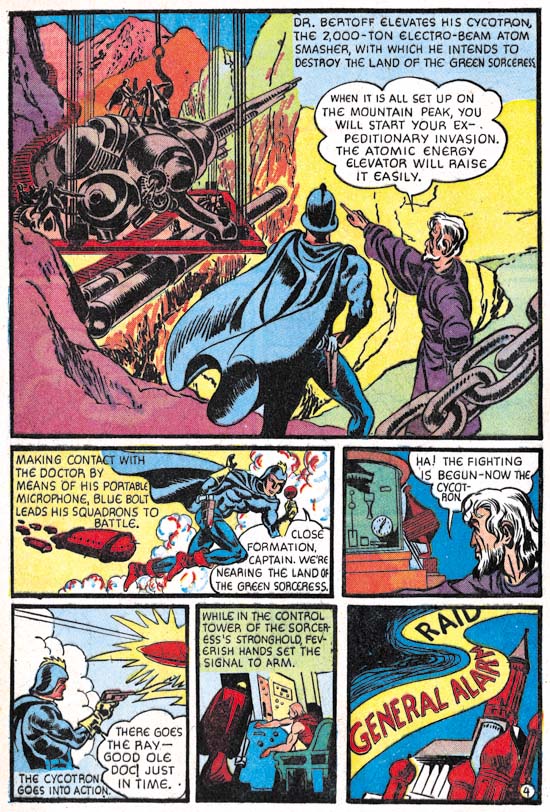

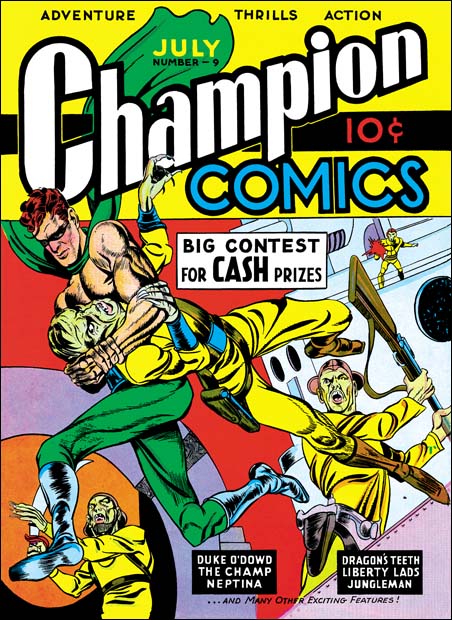

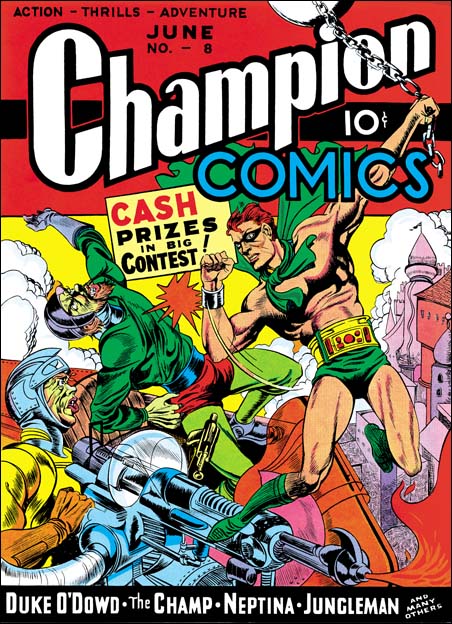

Champion Comics #8 (June 1940) art by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby?

Champion Comics #8 (June 1940) art by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby?