(August 1951 – October 1951: Young Romance #36 – #38, Young Love #24 – #26)

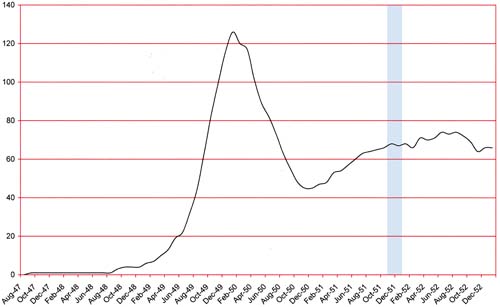

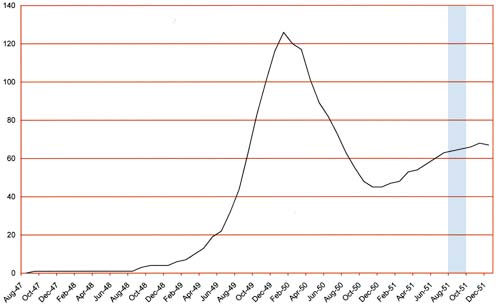

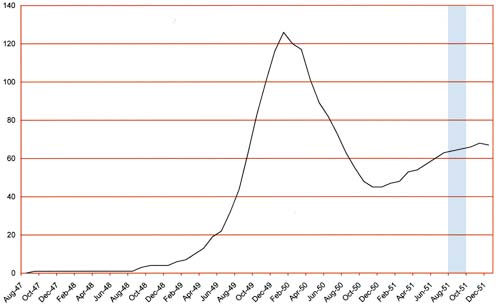

Number of Romance Titles 1947 – 1952 (the period covered in this chapter is shaded in blue)

Despite the fact that today many fans point to Boys’ Ranch as one of Simon and Kirby best efforts it was at the time a commercial failure. The last issue of Boys’ Ranch would have an August cover date. After that Joe and Jack would only be working on the two monthly romance titles and the bimonthly Black Magic all of them for Prize Comics. Young Romance entered its fourth year and I believe both romance titles were still selling very well.

Jack Kirby is legendary for the amount of work he could produce. While there were periods during the Simon and Kirby collaboration that support that legend there are other times that do not. In the previous chapter Meskin replaced Kirby as the most productive studio artist. During the period covered in this chapter Meskin has maintained the first place position but now Bill Draut has replaced Jack for the second place. For the romance titles Meskin produced 64, Draut 49, and Kirby 45 pages. Adding the work for Black Magic only increases the disparity (Meskin 78, Draut 67 and Kirby 60 pages). Mort Meskin was famous for his productivity but Bill Draut was not. The difference is all the more striking when it is considered that Meskin and Draut were doing all there own inking while Kirby was not.

Another indication of Jack’s decreased involvement in the art from this period is that Bill Draut did the lead story for Young Romance #36. While it was not unusual for the first story of Young Love to be done by artists other then Kirby, Young Romance was the flagship title and up to now Jack almost always provided the lead story. The single previous exception was for YR #12 (July 1949) and Draut was the feature artist on that occasion as well.

I cannot offer any explanation for Kirby’s decreased page production. If his time was occupied with trying to develop something new it did not come to fruition. But it must be remembered that Jack was a boss and his income depended on the how good sales were for the S&K titles not on how many pages of art he drew. His decreased output could be due to nothing more then attention to some personal issues.

Most of the rest of the romance work was done by two artists; John Prentice with 25 pages and Marvin Stein with 24 pages. Three other artists supplied single stories. Two of them will be discussed below and the third has not been identified but only provided a single page.

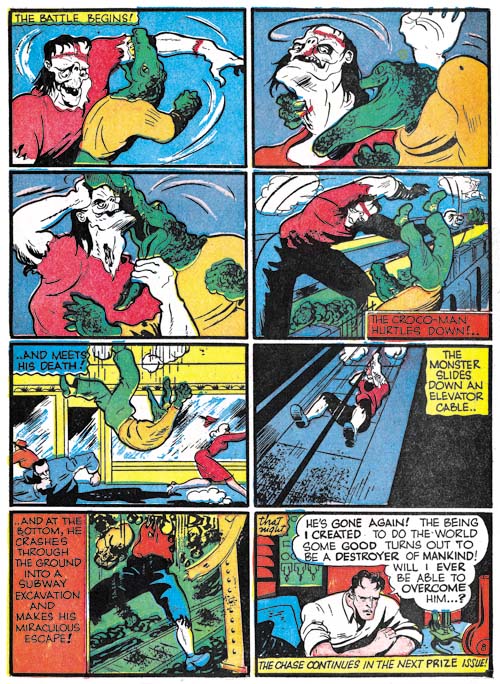

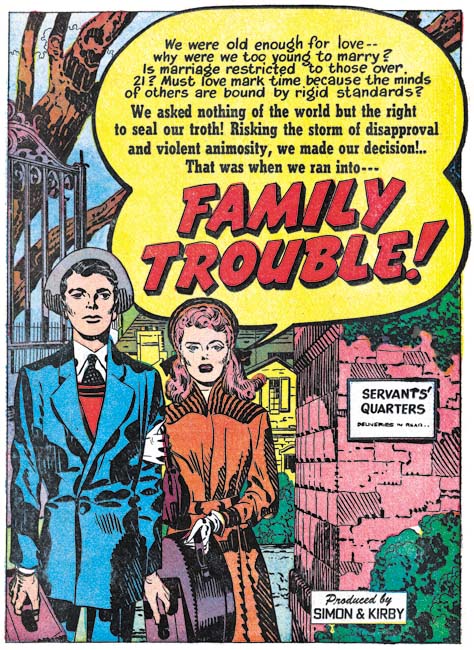

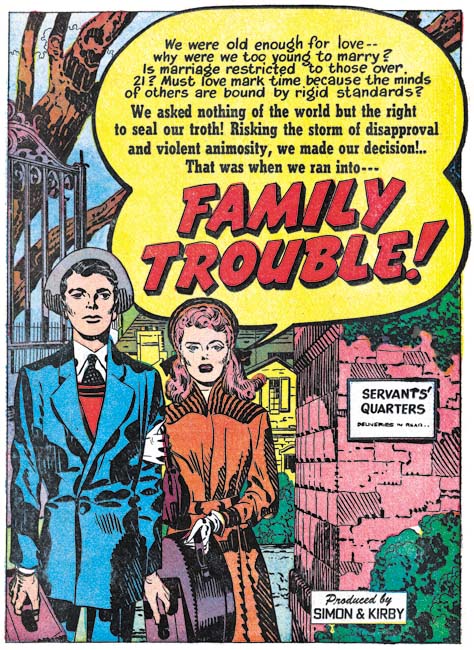

Young Romance #38 (October 1951) “Family Trouble”, art by Jack Kirby

While his page count has dropped the quality of Jack Kirby’s work had not suffered. He still drew great splashes and his stories were still unique compared to other studio artists (suggesting that Jack was rewriting the scripts while he was drawing them). This uniqueness was often the result of placing more action into the story, something that Kirby excelled at. But as I have pointed out before, Jack also excelled at comic book art that did not rely on action. His romance splash panels are often examples of this. The splash for “Family Trouble” uses the confessional format that is so typical of Kirby’s lead stories. The word balloon that introduces the story provides the plot of young lovers facing family disapproval but does not explain the basis of their problem other then age. Kirby presents the couple passing through a gate carrying their luggage presumable off to start their new life together. The sign on the entrance indicates they are leaving the servant’s quarters and therefore theirs is a romance that breaks the class boundary between the rich and their servants. The man seems calmed but resolved while the woman seems more resolute. At a glance this splash is nothing more the two standing figures but Jack embodies an entire story in it. Of course the viewer is expected to be enticed to read the story to get the full explanation.

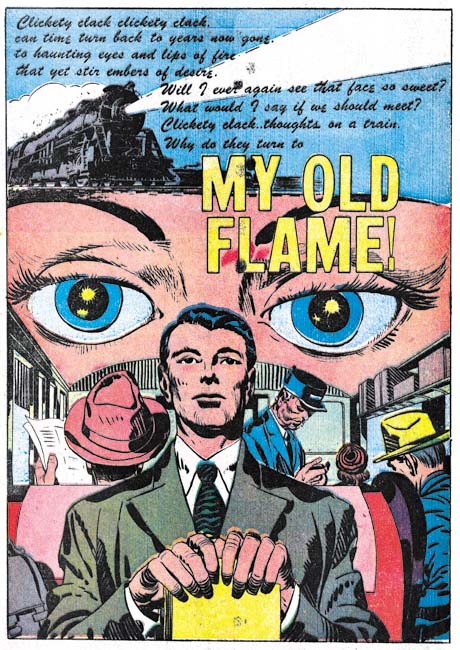

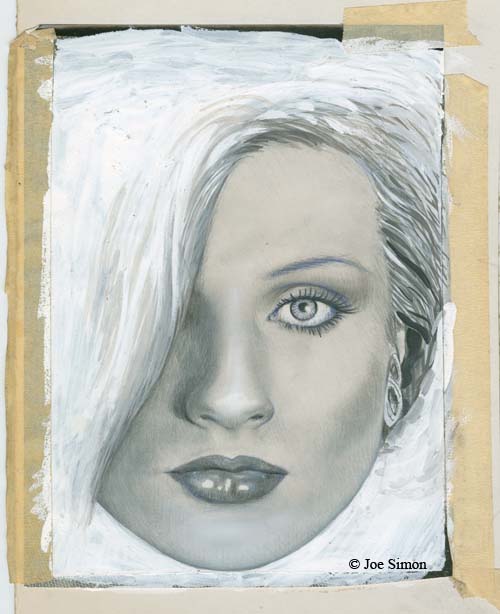

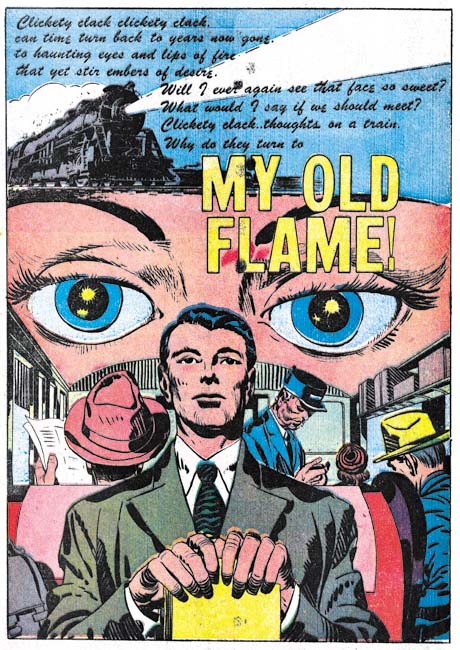

Young Love #25 (September 1951) “My Old Flame”, art by Jack Kirby

Kirby’s splashes are almost always interesting but occasionally they are quite unique. Given Joe Simon’s long history of innovative designs I suspect he provided layouts for many of Jack’s covers and splashes but even if that is true it still took a genius like Kirby to make them work so well. Here while riding a train a man pauses from reading his book to reflect on a past relationship. Normally the splash would be expected to show a head shot or half figure of the former love object. Instead we are provided with just a close-up of a set of eyes seeming arising behind the man; a compositional device that is much more effective in capturing the man’s mood.

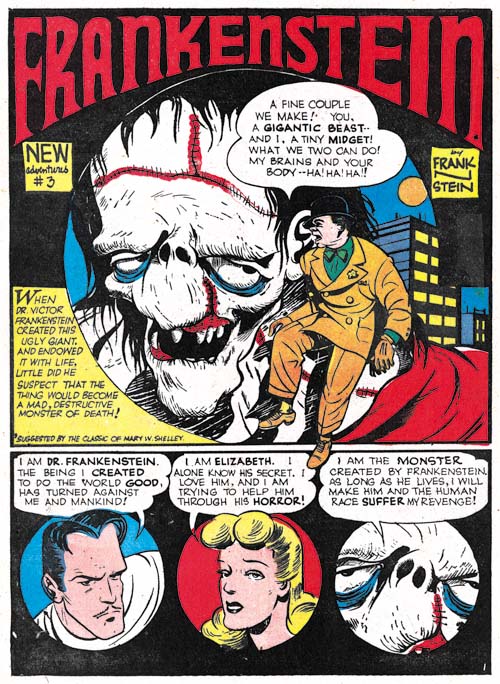

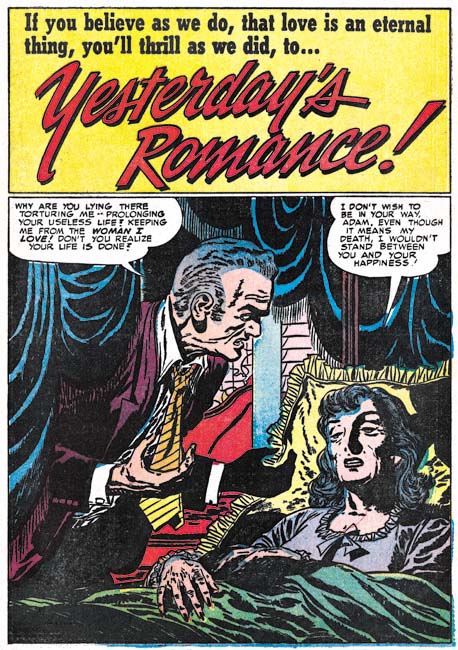

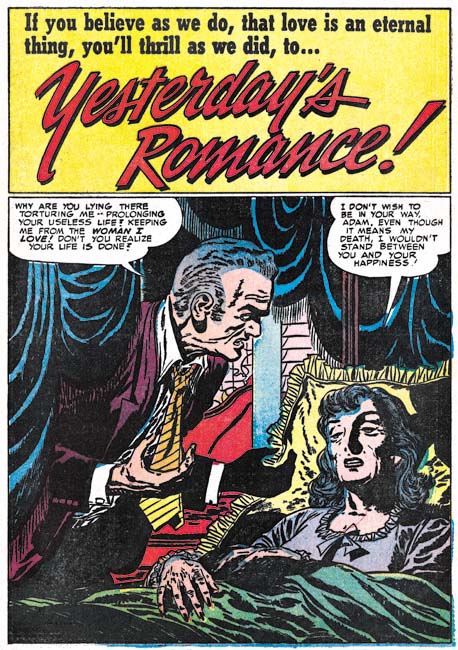

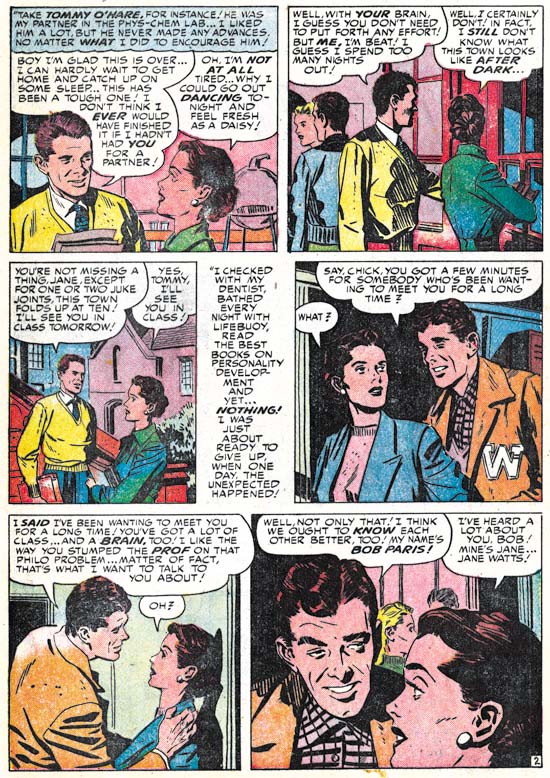

Young Romance #36 (August 1951) “Yesterday’s Romance”, art by Bill Draut

“Yesterday’s Romance” was the lead story for YR #36 that Bill did instead of Jack. It is an unusual story for any romance title because it main characters are all in their advanced years. Draut does a good job of capturing the offbeat nature of the story in his splash. The odd thing about this piece is that usually the lead story used the confessional format where the protagonist’s speech balloon tells what the story is about and provides the title. Bill has used that confessional splash before so he was aware of Simon and Kirby’s preference for using that splash format for the lead story.

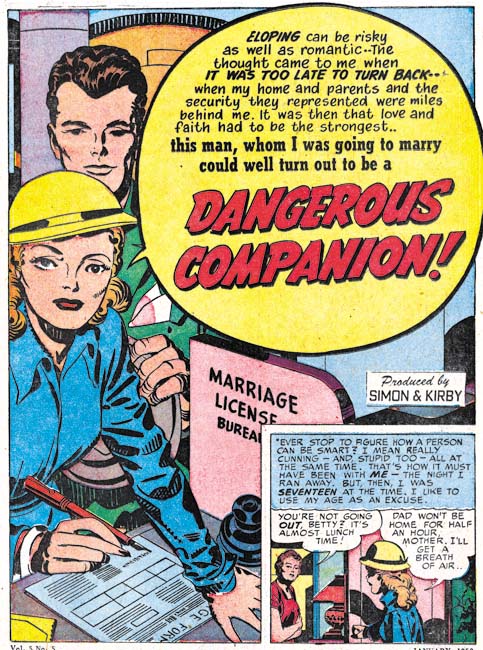

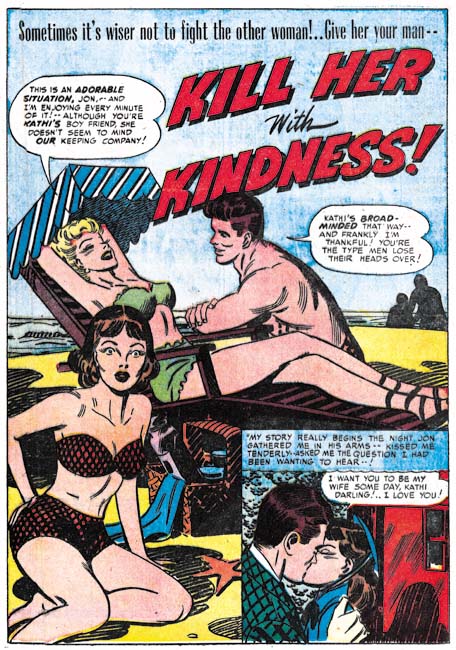

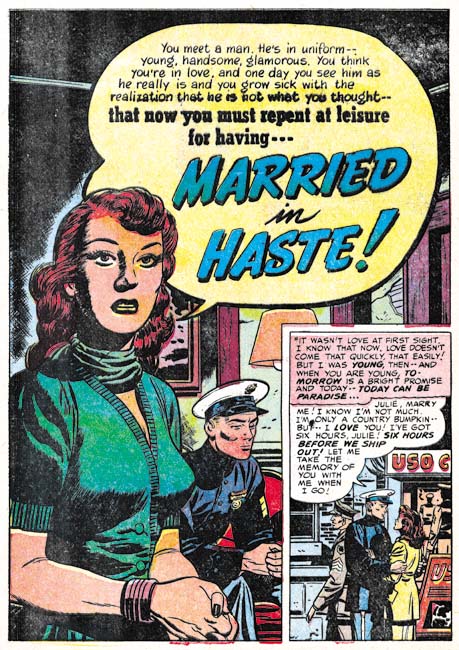

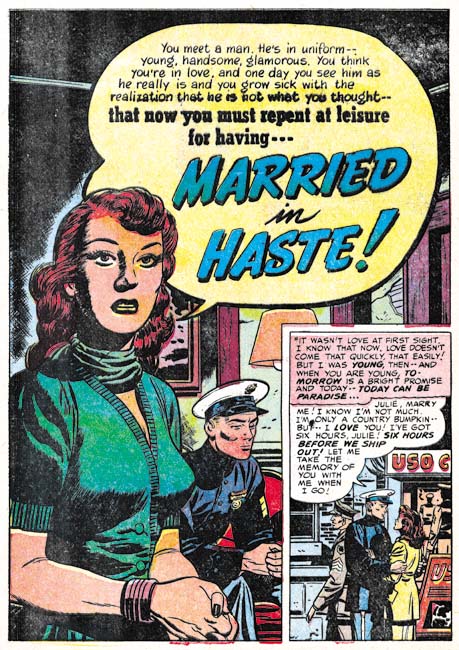

Young Romance #36 (August 1951) “Married In Haste”, art by Bill Draut

While “Yesterday’s Romance” failed to make use of the confessional splash it appears in the same issue in “Married in Haste”. This suggests that “Married in Haste” was originally meant to be the lead story but its place was taken by “Yesterday’s Romance” after the art was completed. Bill does a good job with the confessional splash and as any good splash it succeeds in its roll as the story’s preview. It may not be fair but it is constructive to compare the splash for “Married in Haste” with Kirby’s “Family Trouble” (shown above). Both do well at having the splash background support the story needed although it is not clear how much of this was the result of the artist and how much came from the writer. I describe the comparison as unfair because Kirby is such a great artist the comparison will tend to make Draut’s work poorer then the excellent art it really is. But the comparison is useful because it highlights the nuanced emotions Kirby gives his characters compared to the more static ones that Draut provides. While Kirby is justly famous for the exciting action the work he did for romance pushed him to be equally adept at portraying more subtle emotions.

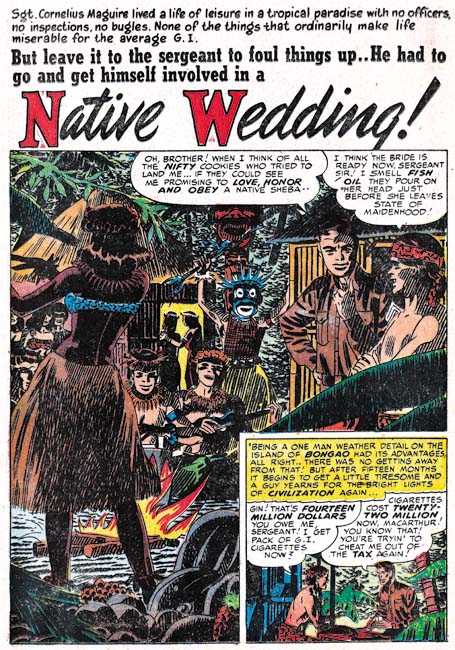

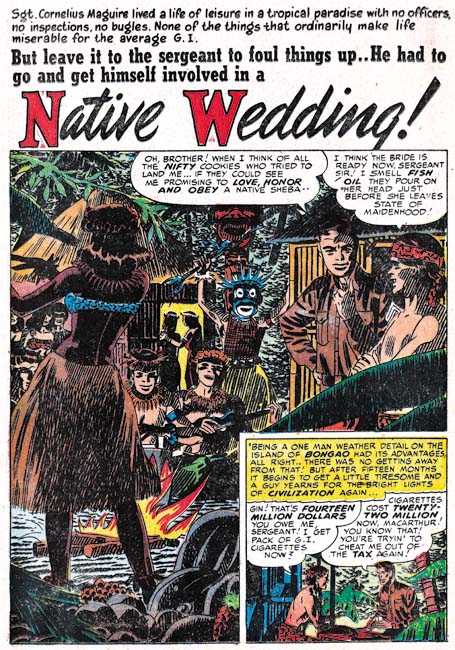

Young Love #24 (August 1951) “Native Wedding”, art by Mort Meskin

The splash for Meskin’s “Native Wedding” is reminiscent of the one Bruno Premiani did some time ago for YR #10 (June 1950, see chapter 11 of The Art of Romance). One obvious difference is that Meskin is uncharacteristic in his use of busy brushwork found throughout the splash. Normally this would result in the image loosing focus but somehow Mort pulls it off. Mort also takes care to make the camp fire scene occur at night providing the nearby faces shadowed from below as appropriate for the position of the fire. The dancer’s back is also appropriately shadowed.

Young Love #26 (October 1951) “Let’s Keep It Gay” page 5, art by Mort Meskin

For a couple of pages of “Let’s Keep It Gay” Meskin adopts and 2 rows by 3 columns panel layout. This results in tall narrow panels that Mort put to good use especially in the second panel of page 5. This panel layout was one that previously Leonard Starr was fond of using so one wonders if perhaps Meskin picked it up from him. Starr also used a 3 rows by 3 panel layout where he would decrease the height of two rows so that the remaining row would have similarly tall panels. Starr’s modified 3 by 3 panel layout did not seem to be one the Meskin picked up on.

I particularly like how the bottom row starts with the couple in the foreground and a TV studio as the background, then Mort comes in for a close-up without the studio background, before ending by once again pushing the couple into the background of the studio. Careful manipulation of point of view was an important aspect of Meskin’s art during this period providing his stories with what could be described as a cinematic approach.

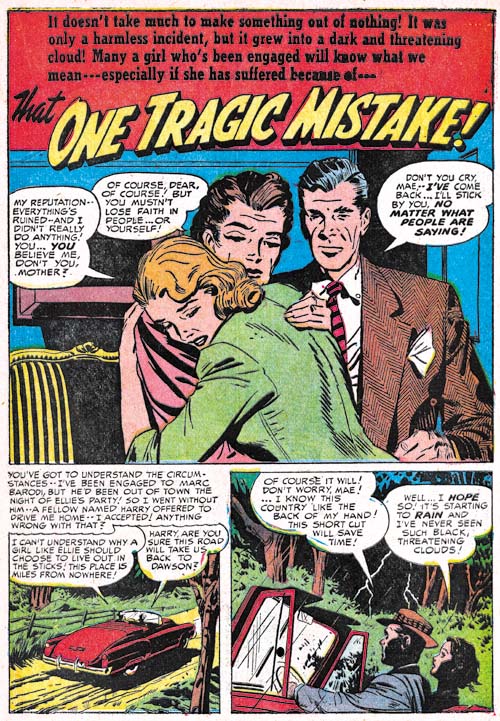

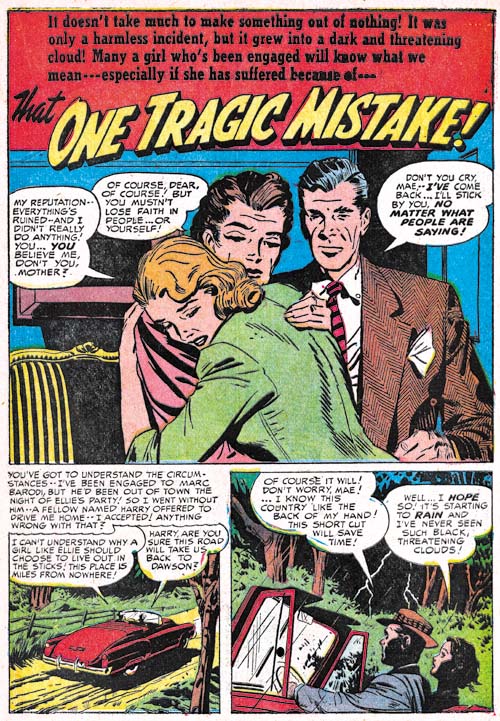

Young Romance #38 (October 1951) “One Tragic Mistake”, art by John Prentice

John Prentice has become a regular presence in Simon and Kirby productions, especially the romance comics. In the last chapter I provided an example where Prentice seemed to be adopting some of the Studio Style inking techniques. Although it was possible it could have been Joe or Jack touching up John’s work the picket fence crosshatching (see my Inking Glossary for explanations of some of my inking terminology) my opinion was and still is that it was the work of John himself. For the splash page of “One Tragic Mistake” we find a more typical Prentice inking. Note in particular his method of doing cloth folds. They are not the spatulate or oval shape typical of Kirby but tend to be long with roughly parallel edges and with a more or less flat and sometimes slanted ends. John also has a fondness for long sweeping cloth folds. Note the inking of the man’s shoulder. At a glance this might be mistaken for a Studio Style shoulder blot but see how it appears on only one of the shoulders and is clearly integrated with the shadow on the side of the face. With Joe or Jack I am never sure if shoulder blots were meant to indicate shadows or the turn of the form but Prentice always seems quite clear with his intent.

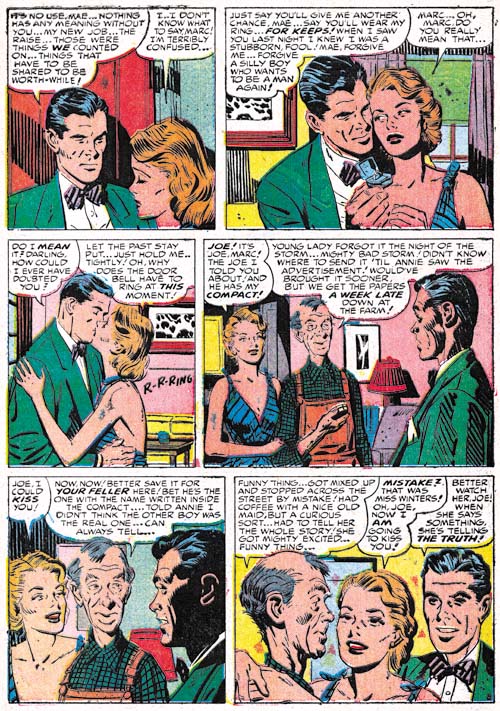

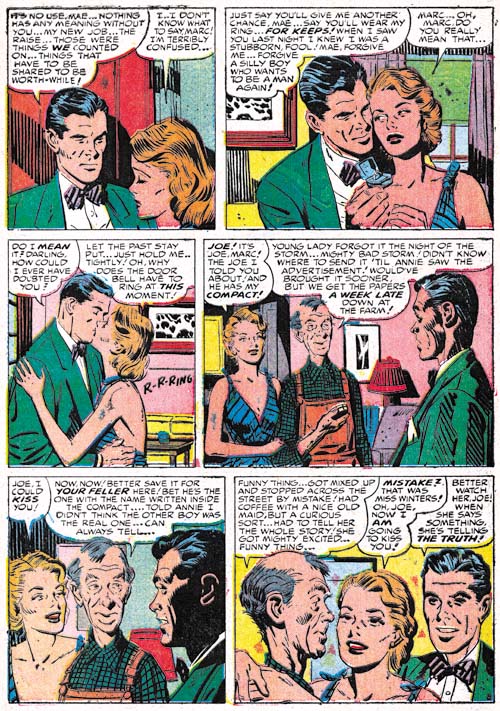

Young Romance #38 (October 1951) “One Tragic Mistake” page 8, art by John Prentice

While the splash page to this story looks like typical Prentice inking other pages seem to be a combination of his own inking techniques and the Studio Style. Most of the cloth folds are done in Prentice’s typical brush work but note the abstract arch shadows (panels 1, 2 and 4), picket fence crosshatching (panels 3 and 4) and shoulder blot (panel 6). Only drop strings appear to be missing. Panel 6 truly has shoulder blots because they appear on both shoulders while a shadow would only be appropriate foe the man’s right side. While I am not certain that the picket fence crosshatching was not by John, the abstract arches are so untypical for Prentice that I believe this is Joe or Jack stepping to do some touching up.

Young Love #24 (August 1951) “Don’t Tell On Me” page 2, art by John Prentice

A page from another Prentice story from the same period provides a more typical example of Prentice inking. Again note the cloth folds some of which are long and sweeping and few could be called oval or spatulate in shape. There are some arching shadows that might suggest the Studio Style. But the round shape in the first panel is not abstract at all but is clearly meant to be the moon. The arc of the left side of the second panel is meant to be the entrance to an arched hallway. The shadow on the right side seems to be the light of the window falling on the darken exterior. Almost all applications of large areas of ink appear to be intended as realistic shadows. There is some picket fence crosshatching that again does not look typical of the brush work of either Kirby or Simon. However note the picket fence crosshatching of the last panel. The pure black area on the man’s left shoulder seems an appropriate shadow but then the picket fence crosshatching on the opposite side does not. Since I have found both Simon and Kirby touching up other artists works distinguishing between their efforts and that of the original artists adopting Studio Style techniques can be a difficult conundrum. In John Prentice’s case I am still undecided. The distinction becomes important when trying to detect Prentice’s hand in the inking of work by Jack Kirby. Some have suggested that John was the inker for some of Kirby’s art and he certainly is a candidate for that type of work.

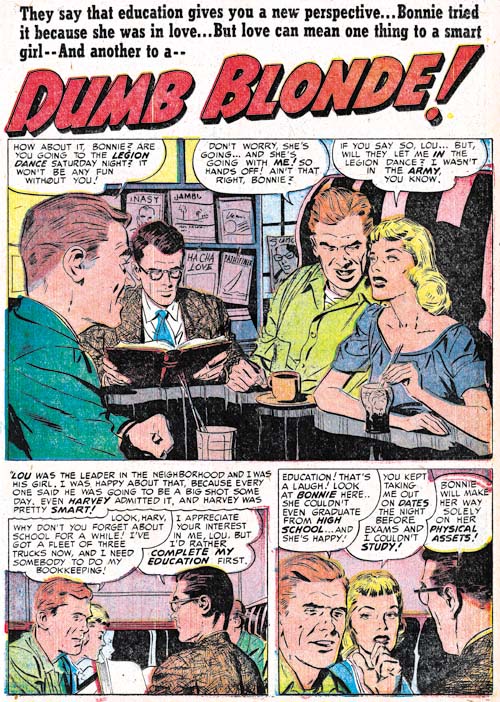

Young Love #24 (August 1951) “Left At the Alter”, art by Marvin Stein

Previously I have had mixed feelings about Marvin Stein and in particular felt his romance art was little more then adequate. Even in the last chapter I noted his presence and gave an example image but did not provide more detailed examination. However Marvin had been working hard at improving his art and although signs of improvement have been noted before now his efforts really seems to bare fruit during this period. Marvin developed a style for his crime and western work that owed much to what he learned from Jack Kirby. For that more action oriented art Stein also developed an inking style that was blunt but well controlled; a style very suitable for the genre it was used on. Neither the pencil nor inking style would be very appropriate for romance work so instead Marvin used a more refined style for both. Not only was the bold inking brush restrained but Marvin sometimes used a pen to create crosshatching. His figure drawing has improved but he still retains one of his earlier trademark tendencies to give his woman eyes that are set at an angle with each other.

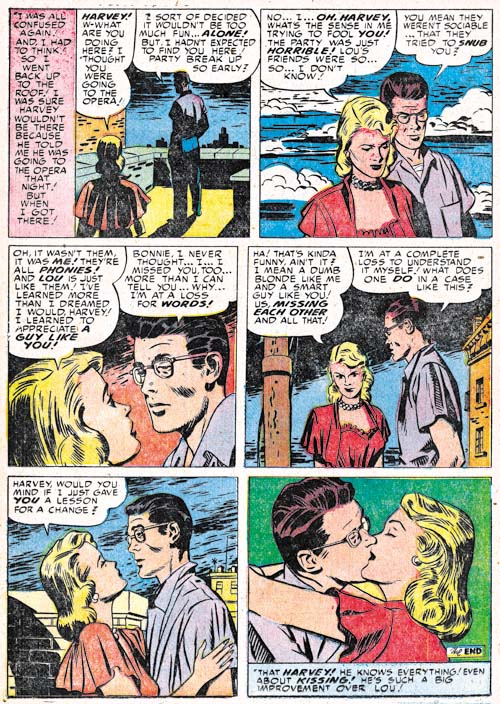

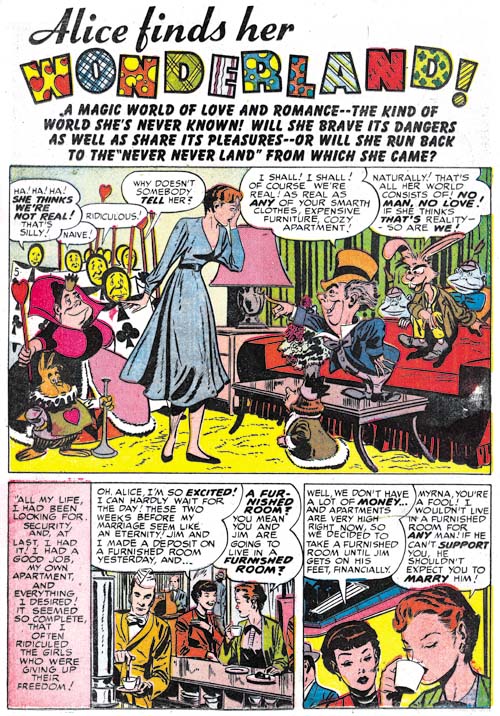

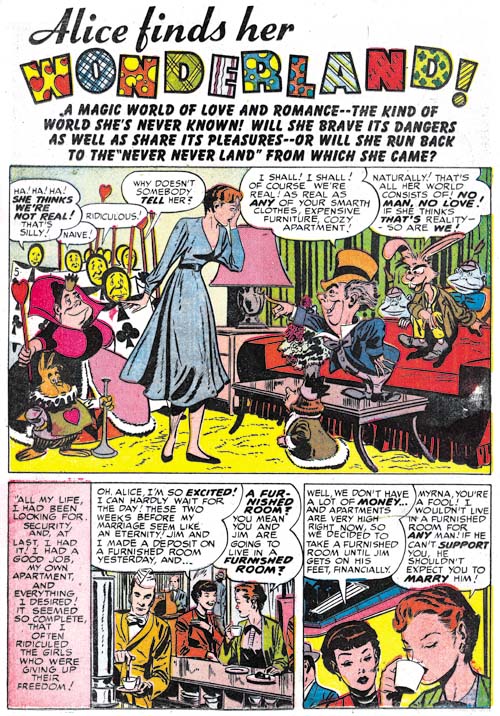

Young Love #25 (September 1951) “Alice Finds Her Wonderland”, art by Marvin Stein

The splash for “Alice Finds Her Wonderland” is so special I could not resist including it. The Alice in Wonderland cast was probable requested by the script writer although the wonderland that Alice desires in the story did not include these delightful characters. Having seen much of Marvin Steins work in the romance, crime, western and horror genres it is quite a pleasure to see him so successful at a more cartoon-like drawing.

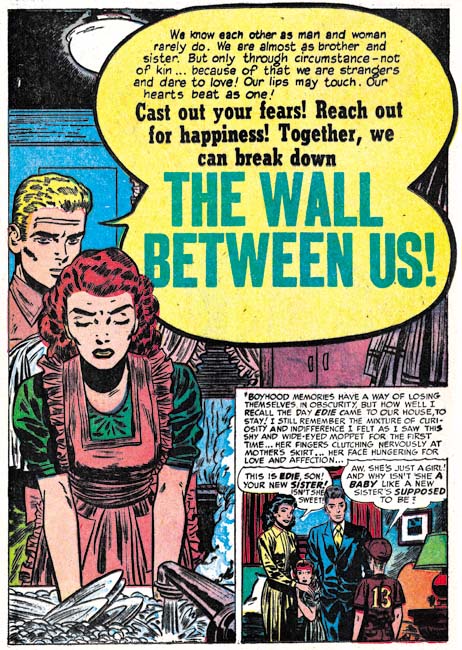

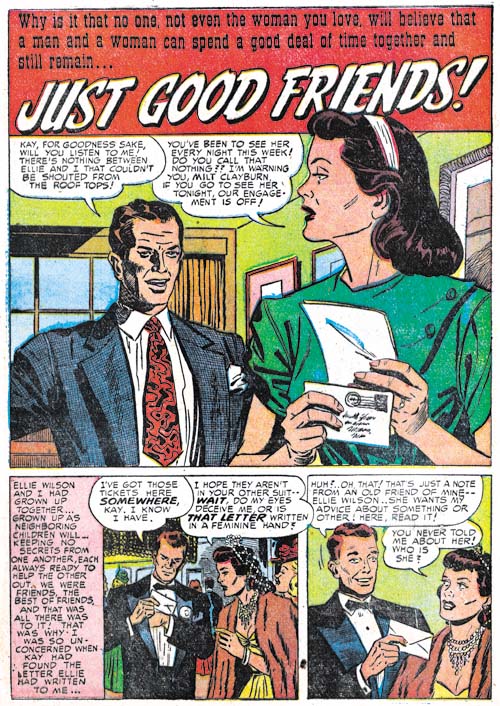

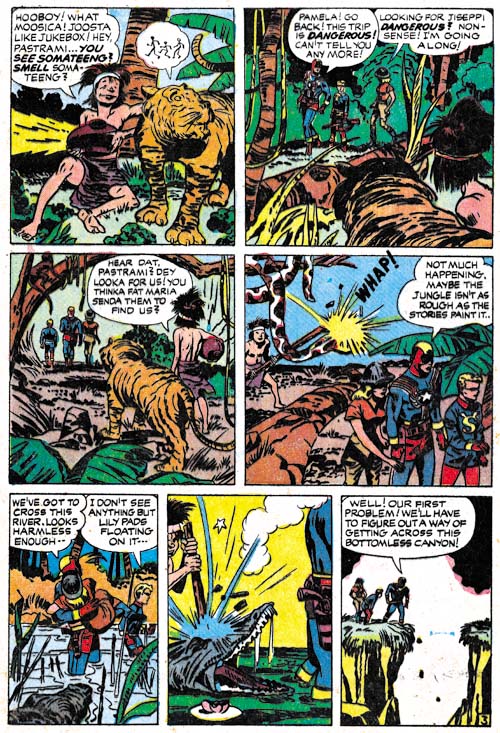

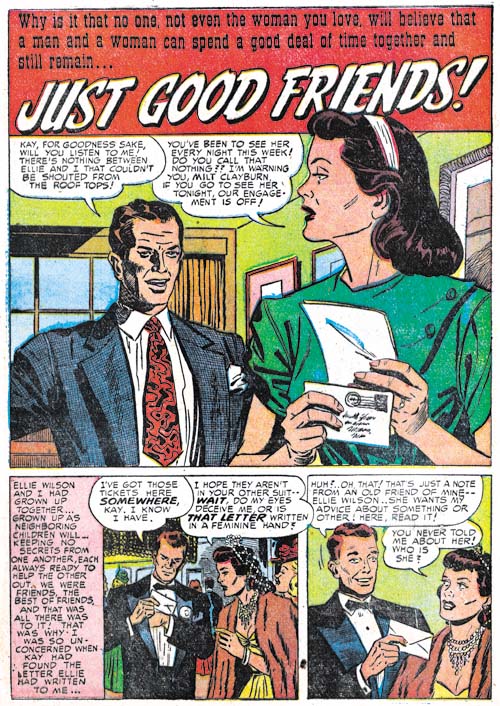

Young Romance #36 (August 1951) “Just Good Friends”, art by Vic Donahue

Vic Donahue has not made an appearance in a Simon and Kirby production for almost a year (last seen in YL #13, September 1950, see Chapter 11 of The Art of Romance). Even then I remarked that his art had been improving. Apparently that improvement has progressed so far that I almost did not recognize him in “Just Good Friends”. Even though this piece is unsigned enough of Vic’s mannerisms remain to credit Vic with this story such as the tilt he often gives the heads of females or the way he occasionally reverts to fine pen work often as simple hatching. Vic also appeared in this same month in Black Magic #6 (Chapter 2 of the Little Shop of Horrors) in a signed piece but I have to admit I did not find that work particularly appealing.

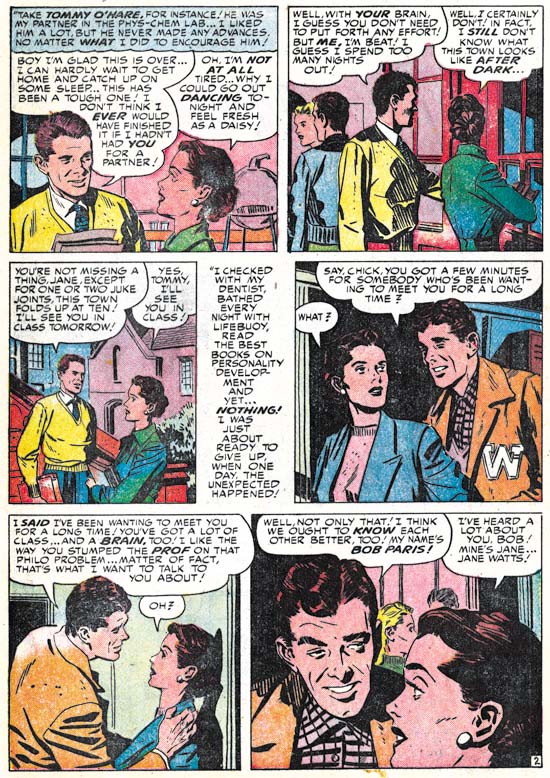

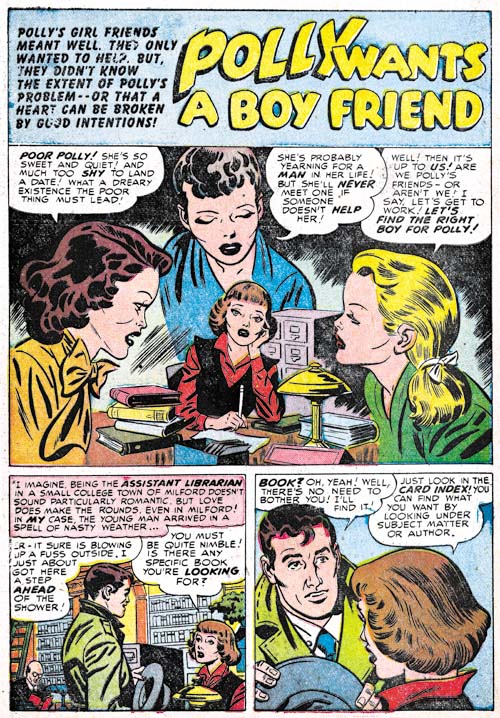

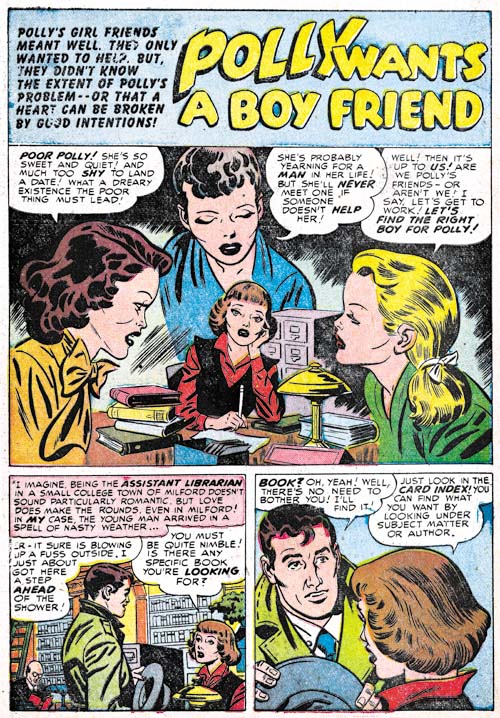

Young Love #26 (October 1951) “Polly Wants a Boy Friend”, art by Ross Andru

I am always impressed by the number of talented comic book artists that had worked for Simon and Kirby at one time or another. Some like Bill Draut, Mort Meskin and John Prentice did extended stays. Others like Leonard Starr and John Severin worked for more limited durations but provided their share of work during that time. Yet others made brief appearances and only did a few pieces for instance Bernie Krigstein and Steve Ditko. Ross Andru belongs in the last category.

I must admit that I am not that knowledgeable about Ross Andru’s history. Most fans are probably familiar with him for the work he did many years later on Amazing Spider-Man. Andru was clearly an enterprising individual who formed his own company on three occasions. The earliest was in 1951 when he and Mike Esposito created MR Publications. I am not clear exactly what the nature of this company was. Some have said it was a comic publishing company in which case Andru and Esposito were three years ahead of Simon and Kirby’s Mainline (although Al Harvey was much earlier then them all). However I have been unable to determine what comic titles they published. If MR Publications was actually producing comic books for another publisher to release then Simon and Kirby had been doing that for years (and Will Eisner doing it still earlier). MR Publications was short lived and it would be interesting to determine the timing of that company or its demise and the appearance of Andru’s in Simon and Kirby productions.

“Polly Wants a Boy Friend” is typical romance work by Andru. The sort of wistful expression with tilted head of the woman in the center of the splash panel can be found in some signed pieces from a few years later. The man in the last panel of the page was also a dead giveaway of Andru’s style. Although unsigned I have not doubt about the correct attribution of this story. My database indicates Ross will appear in a couple more Simon and Kirby romances in the near future and again under different circumstances in 1954. Considering that Andru’s earlier pieces for Joe and Jack are unsigned there is also the possibility I will find more as my reviews progress.

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)