(Clue Comics vol. 2 num. 1 – 3)

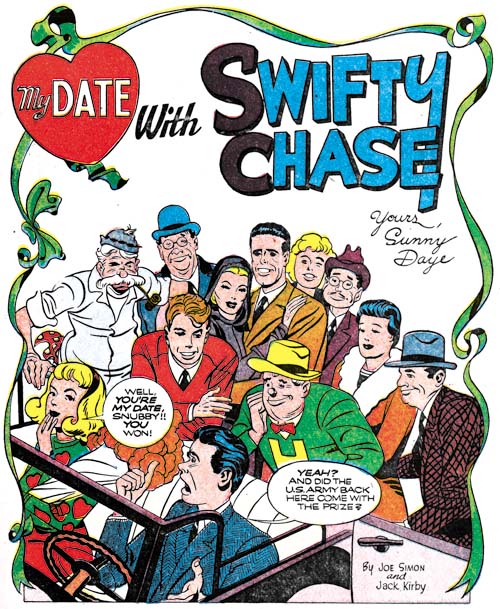

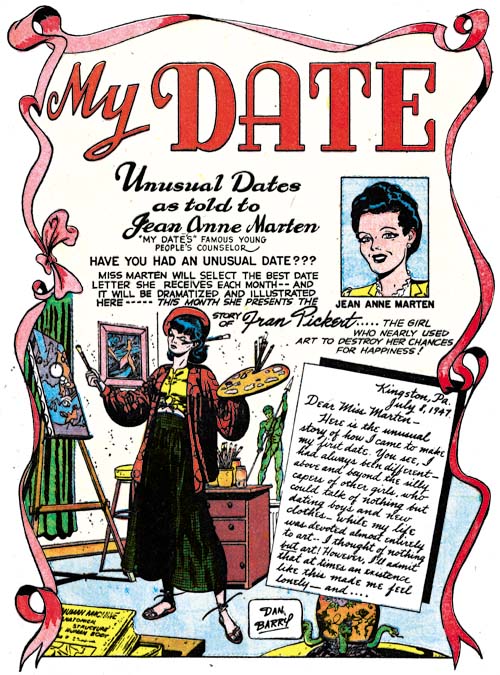

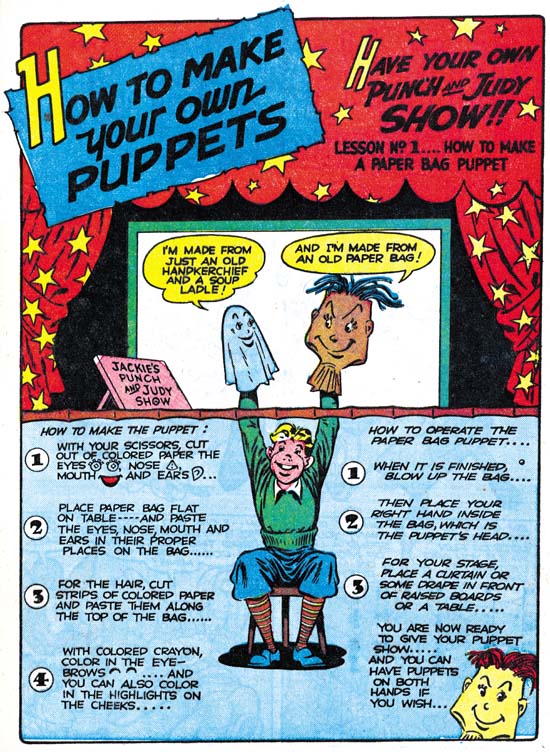

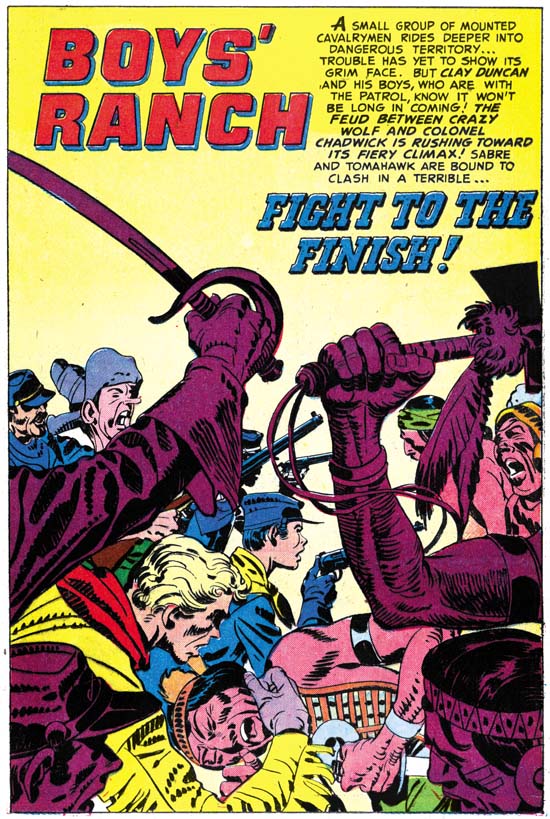

The same month that the first crime version of Prize Comic’s Headline was released, Simon and Kirby also appeared in Hillman’s Clue Comics (v. 2, n. 1, March 1947). Over the rest of the year Joe and Jack would do a wide variety of work for Hillman Publications; a Caniff style adventure (“The Flying Fool” in Airboy Comics), funny animals (“Lockjaw the Alligator” and “Earl the Rich Rabbit” in Punch and Judy Comics), teenage humor (My Date Comics) and crime (Clue Comics and Real Clue Crime Comics).

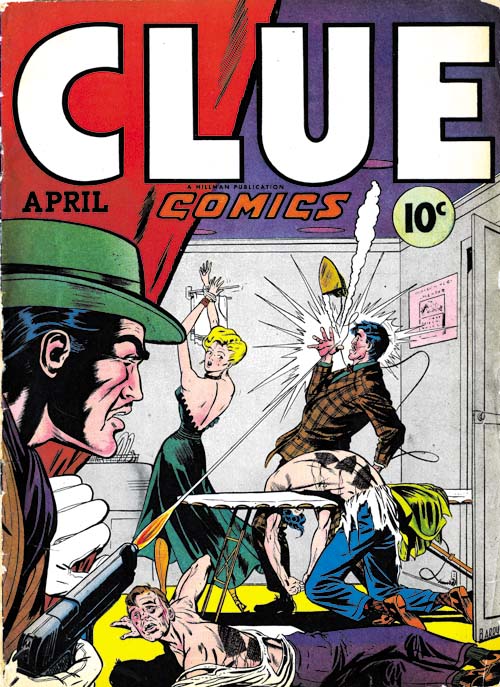

Clue Comics had started out in January 1943 as a hero genre anthology. The covers featured the costumed hero, the Boy King, and the interior included features such as Nightmare and Micro Face. It must not have been very successful because it began as a monthly, switched to a being a bimonthly with issue #4 and then quarterly with issue #8 before being put on hold after issue #9 (Winter 1944). Hillman rebooted Clue Comics after the war (cover date October 1946) and introduced Gun Master as the cover feature. Gun Master gave a more crime genre feel to Clue Comics but it remained as essentially a hero anthology with Nightmare and Micro Face continuing to be included. The revamped Clue must have been successful because it started as a bimonthly but switch to being a monthly with the March 1947 issue.

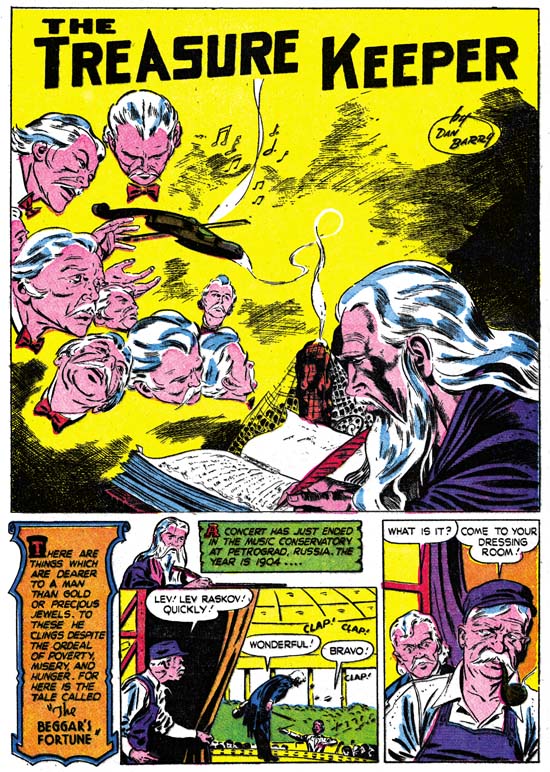

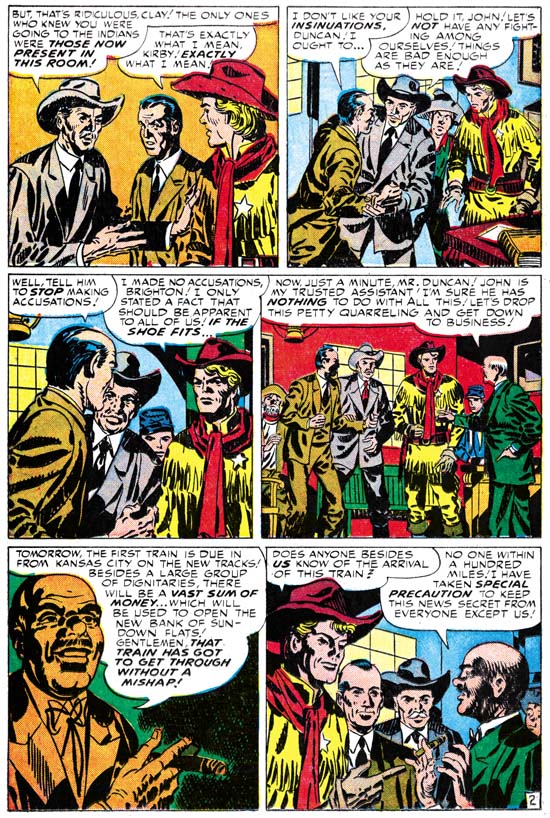

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 2, April 1947), art by Dan Barry

Since the Gun Master did not wear a costume or have any super-powers, the covers for Clue very much had a crime genre feel to them. This can particularly be seen in the cover for the April issue shown above. This cover drew its inspiration from the more graphically brutal covers that some crime comics then used. The depiction of torture by electric iron certainly appeals to the more prurient tastes and goes way beyond what artists like Simon and Kirby would ever produce. The April cover is a bit exploitive and misleading as it does not represent the type of stories actually included in the comic book. Hillman would not repeat such a graphic depiction again for any cover of Clue Comics or the later Real Clue Crime Comics.

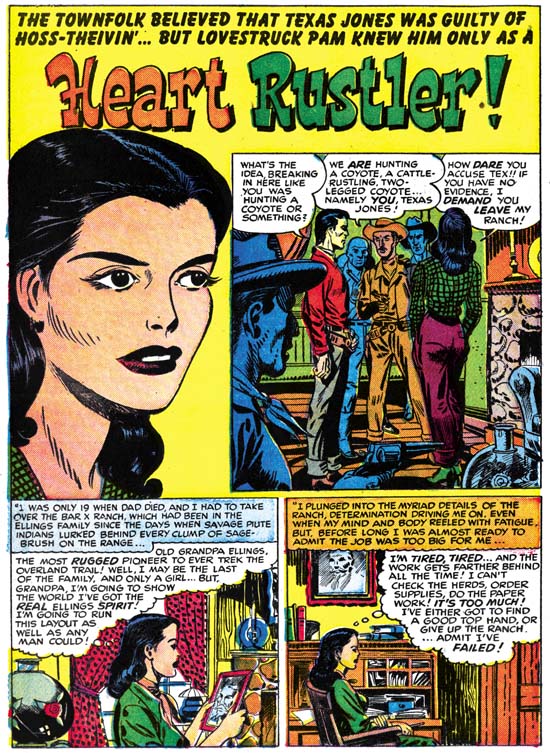

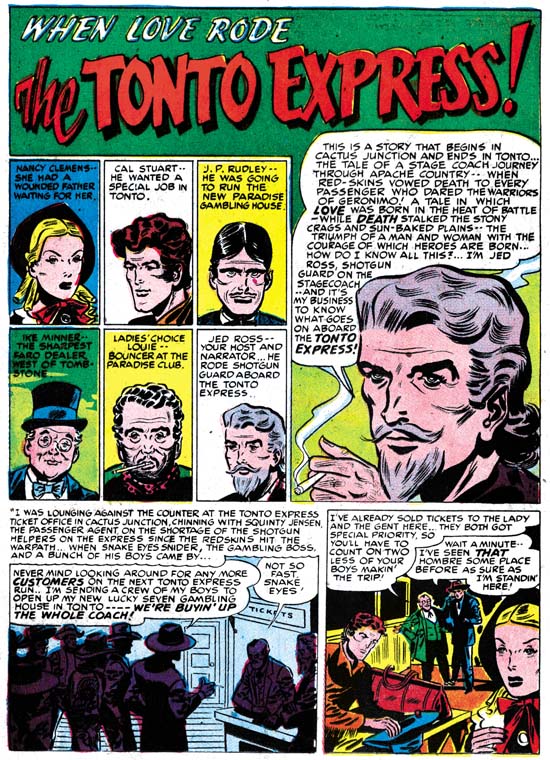

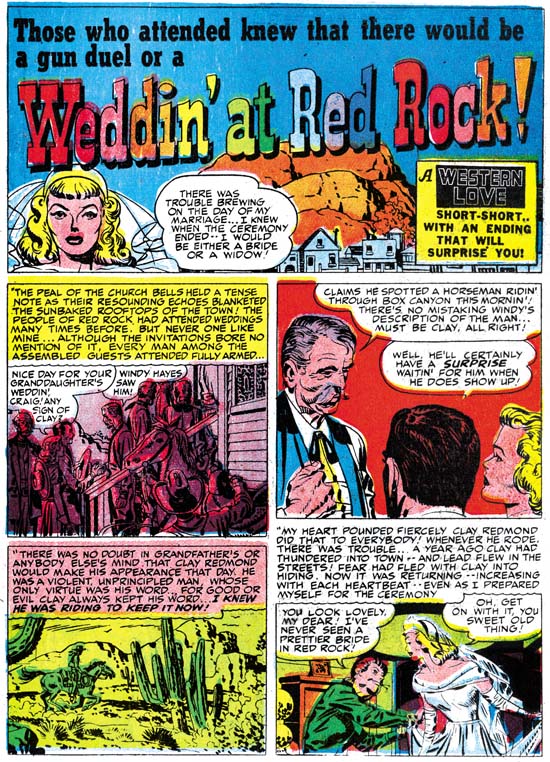

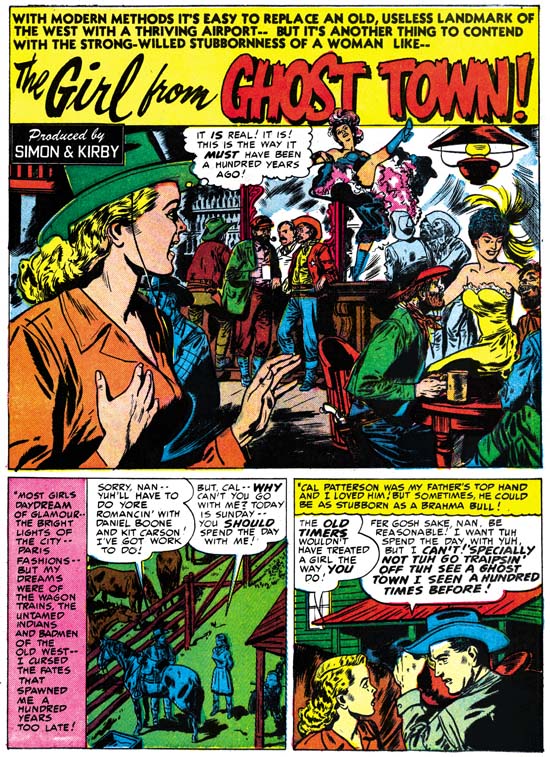

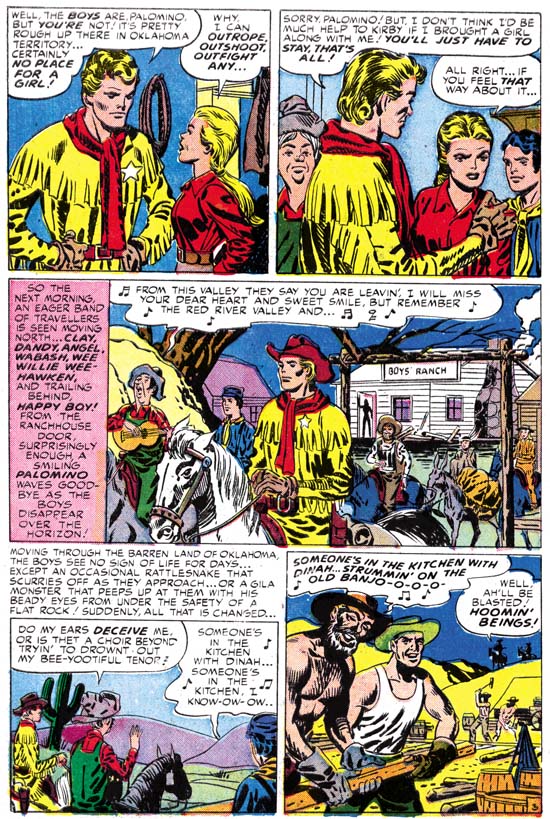

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 1, March 1947) “Gun Master”

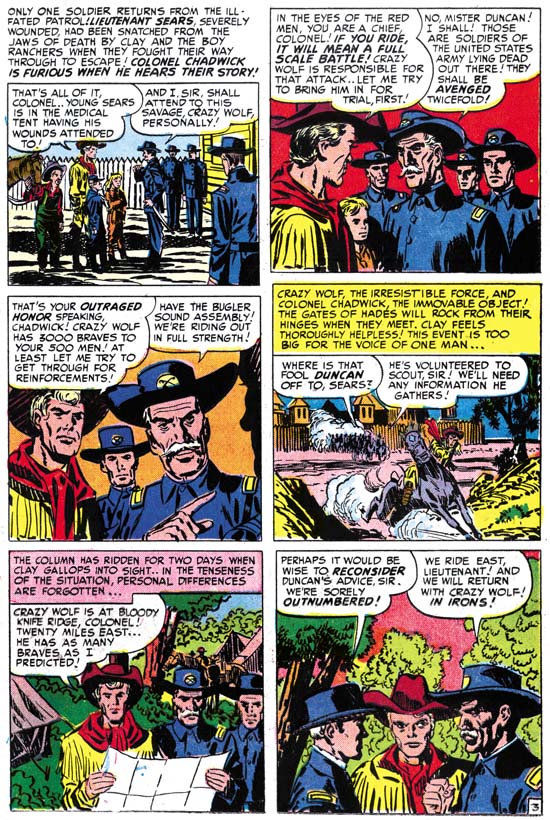

With the March and April issues, Gun Master played an even greater roll for Clue Comics as there were now two Gun Master stories in each issue. If Gun Master’s uncannily accurate ability with a pistol were not enough to convince one that he really belongs in the hero genre then perhaps the Council of Elders will. They were mysterious robed figures who directed the Gun Master. Not the sort of story device expected to be used in a typical crime story.

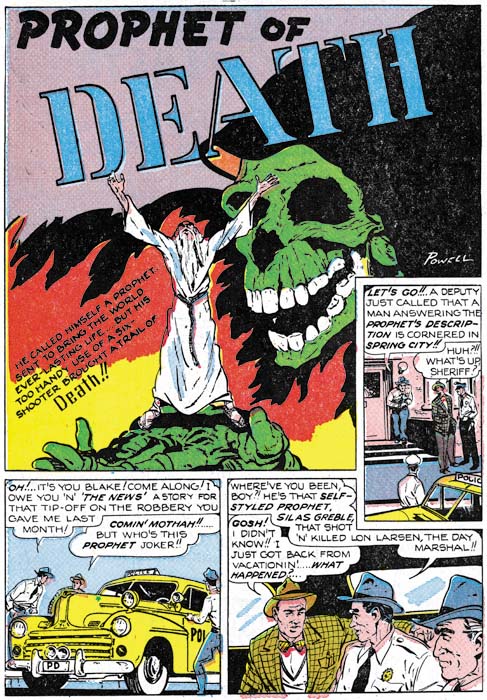

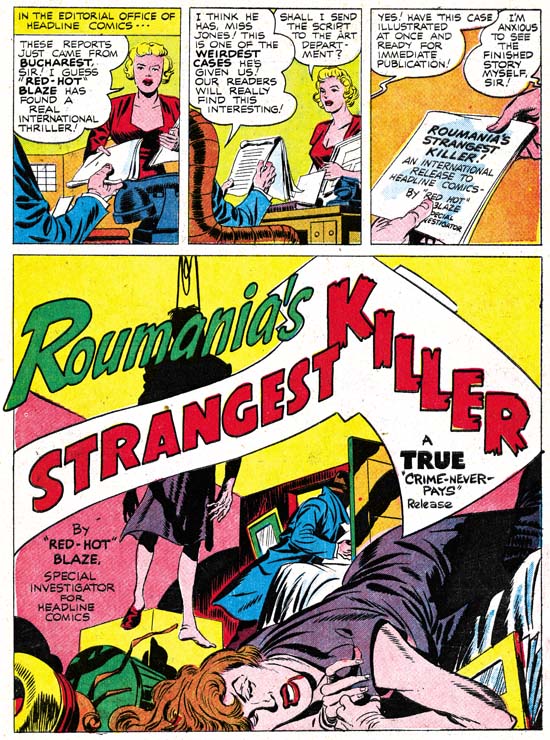

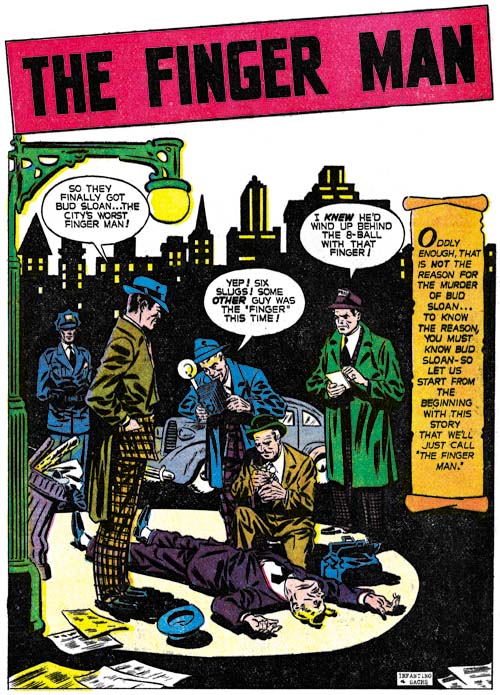

I do not know who the artist was for the above splash, but despite the complete lack of any real action he has managed in any case to make it interesting. Much of the effect of the splash is due to the low viewing angle and unnatural but effective perspective. From such a low view point the sides of the buildings and lamp post should converge towards the top but diverge instead, giving the scene an other-world appearance. The architectural details enhance the strangeness of the scene which I suspect is meant to be in Europe. Perhaps the weakest element of the splash is the upper of the two dead men. The way he is prompt up on his elbows seems unstable and unexpected for a corpse.

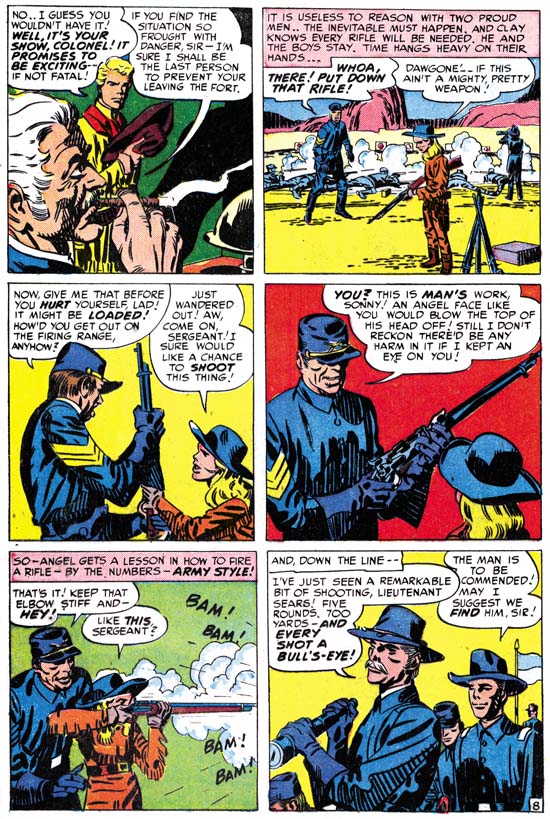

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 1, March 1947) “Iron Lady”

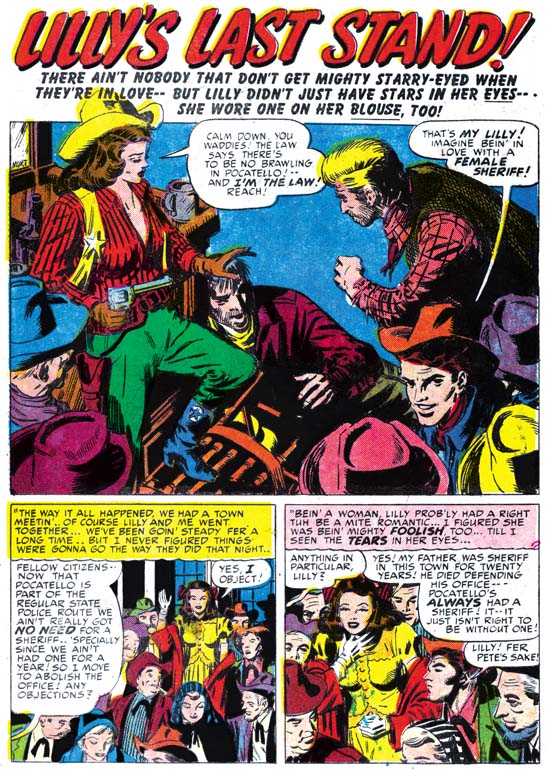

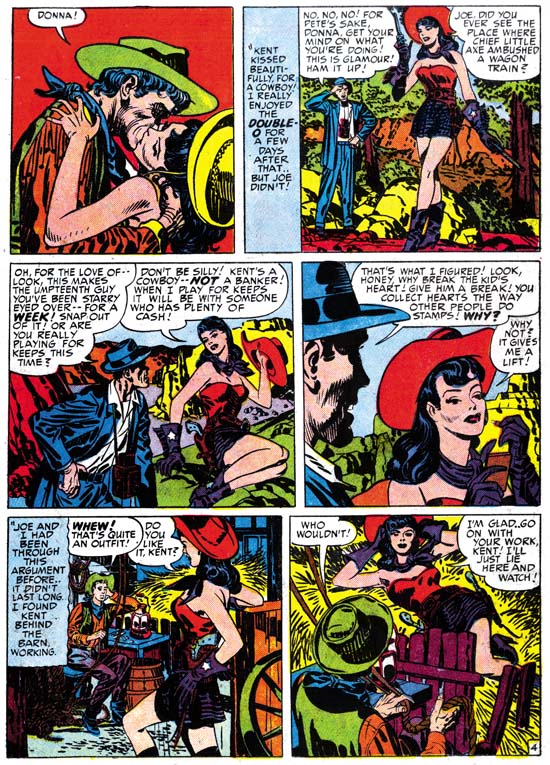

A new feature, “Iron Lady”, was added to Clue Comics that both gave the comic a more crime comic feel while actually making the title untypical for that genre. “Iron Lady” was a feature about a female villain. Such an anti-hero theme had been used previously (such as The Claw) and female lead characters were also not that unusual but I am not sure if the combination had ever been done before. Her use of special gloves that gave her great strength shows once more that this really is not a crime story. Iron Lady’s appearance in Clue Comics is not her debut as I believe she appeared previously in Airboy Comics.

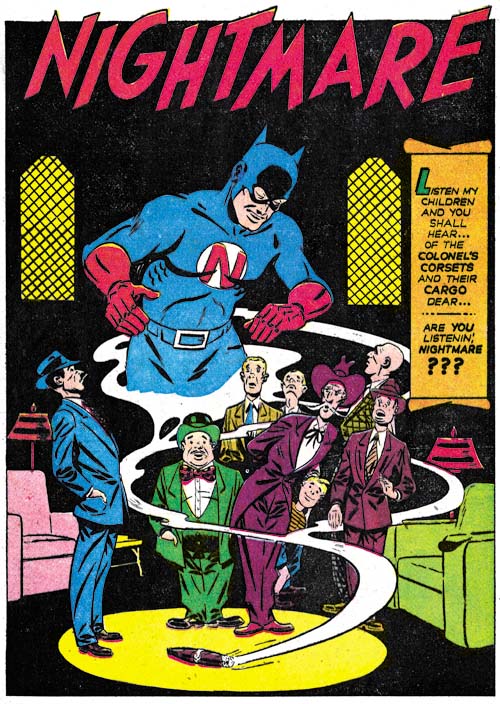

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 2, April 1947) “Nightmare”

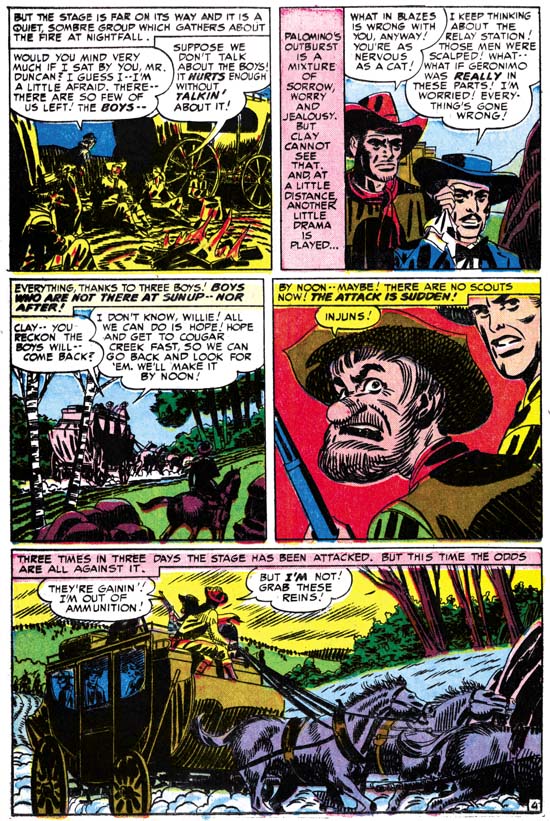

The revamped Clue Comic still retained some of its older features. Nightmare appeared in the March and April issues while Micro Face showed up in the May release. Judging solely by the covers of the early issues of Clue Comics, Nightmare originally had a young sidekick who somewhere along the line had been dropped. This hero appears from the smoke of a cigar which is reminiscent of the Flame from Fox Comics or Simon and Kirby’s Vision for Timely. Micro Face has a peculiar face gear that almost looks like a welder’s mask. These two costume heroes certainly work against the crime genre look that the revamped Clue seemed to be striving for.

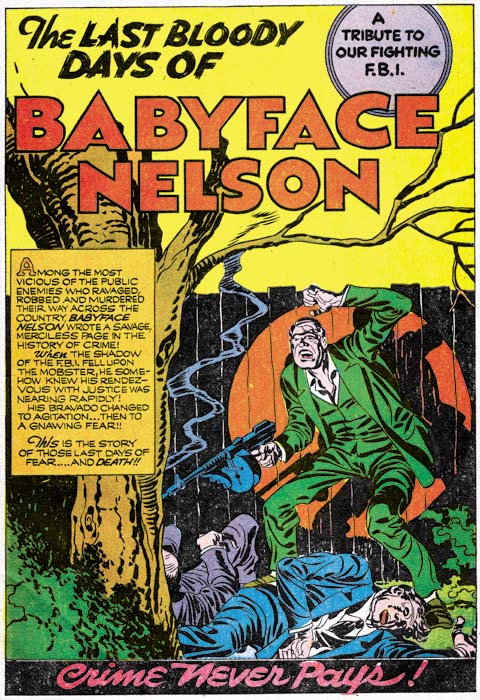

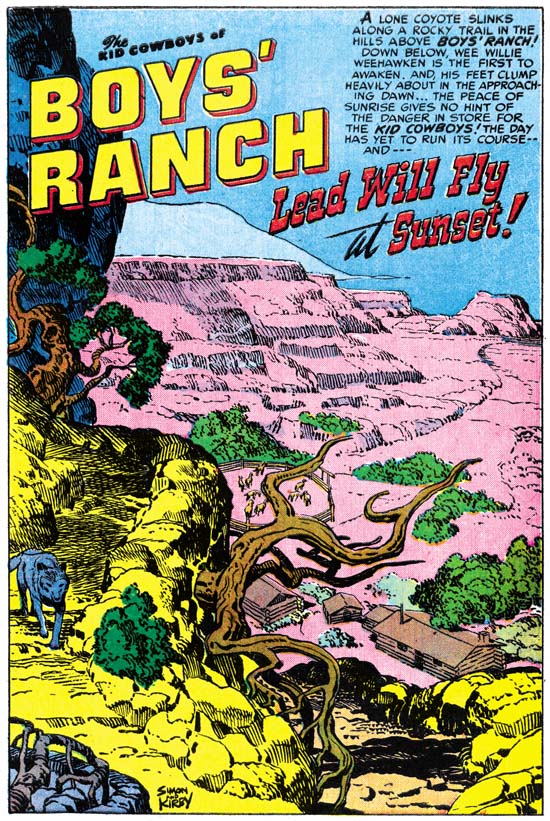

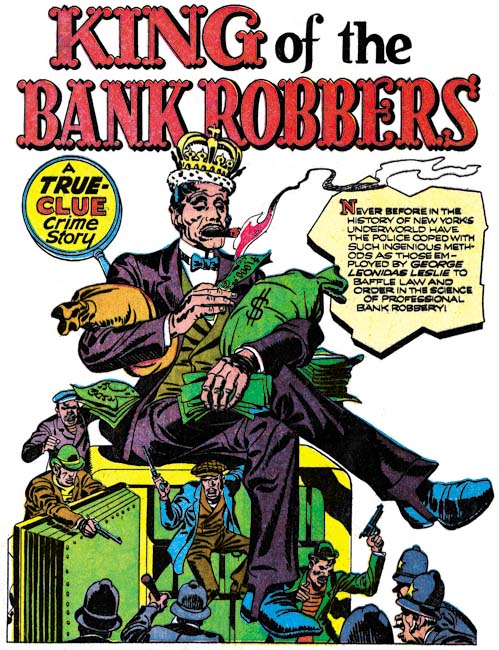

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 1, March 1947) “King of the Bank Robbers”, art by Jack Kirby

The Simon and Kirby’s contribution to the March 1947 issue of Clue was unabashedly crime genre. It was supposedly a true story and considering it was a period piece it probably was based on some real life criminal. No special powers here, just the career of a colorful criminal and his eventual downfall. Despite its short term attractions, in the end crime does not pay. The use of an oversized figure in the above splash is unusual for Jack Kirby particularly when doing crime comics. I tend to believe that when such oversized figures were used it was based in part on a Simon layout as oversized figures played a part in Joe’s art both before and after working with Jack.

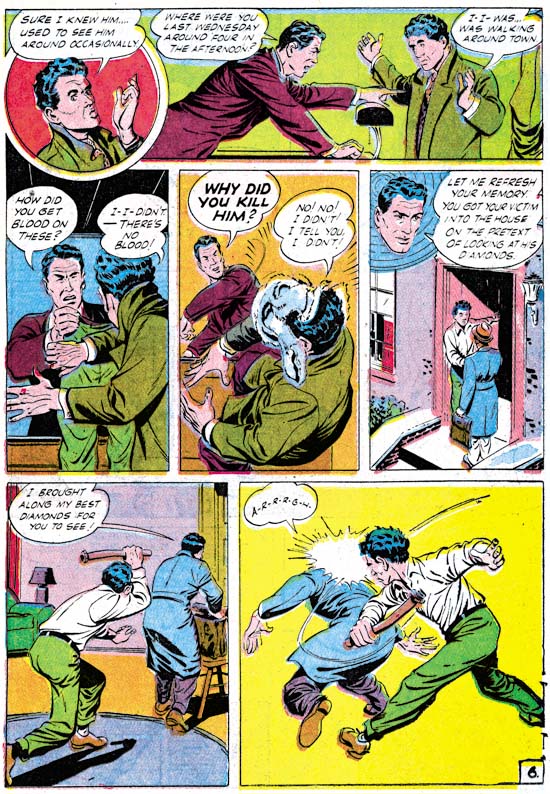

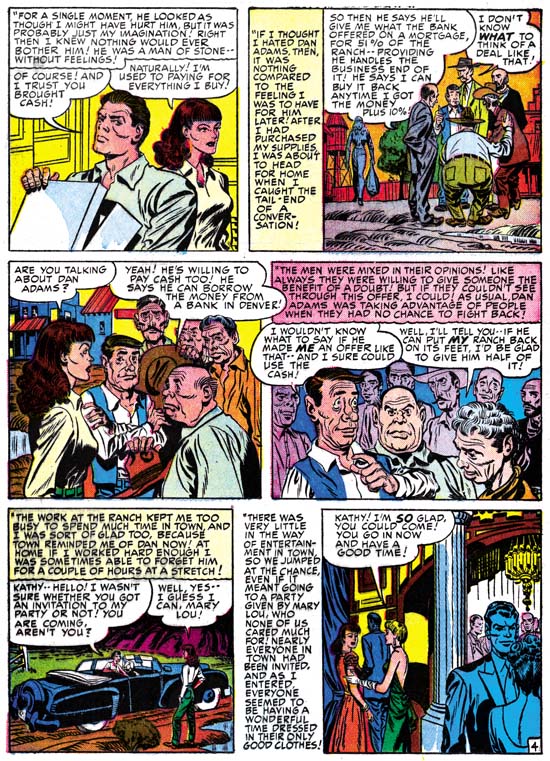

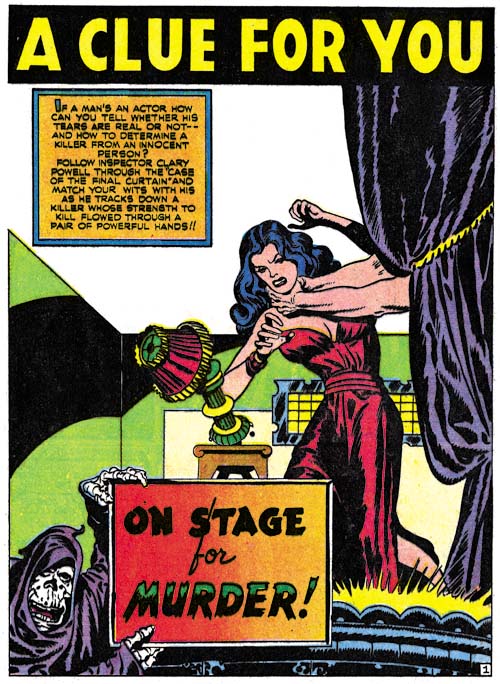

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 2, April 1947) “On Stage for Murder”, art by Jack Kirby

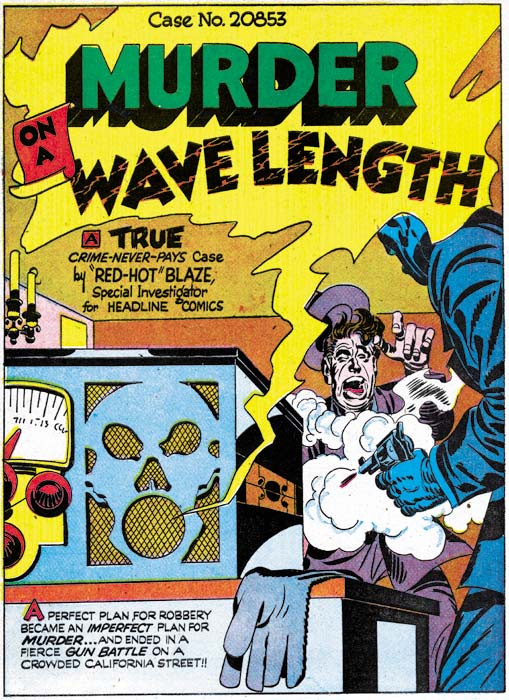

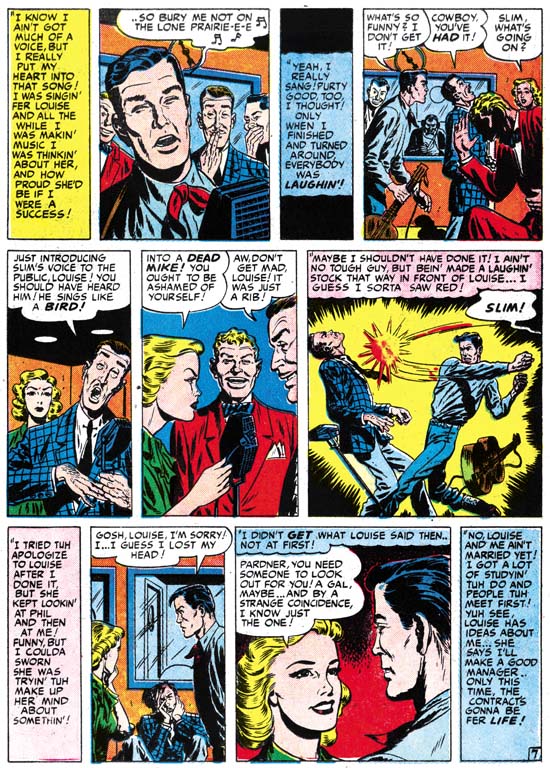

There was only a single Simon and Kirby piece in the March issue but their presence increased as they did two stories for the April issue and three for May. The art work done in the Clue Comics seems to be indistinguishable from that appearing concurrently in Prize’s Headline. This includes the type of inking done. In the previous chapters I have described this as part of the Sculptural style. Actually the use of style names is for convenience as inking used by Simon and Kirby was continually evolving and there really were no distinct breaks in the type of inking used. To lump it all together would mean to ignore the real changes that were made, but to divide the inking too finely into different periods would just confuse the issue. As I have been reviewing the art for this and the serial post “The Art of Romance” I have been coming to the realization that although during this period Simon and Kirby have not adopted all the characteristics of the coming Studio style of inking, they also were no longer working in quite the same manner as they had used during the war. In particular there was less emphasis on what I call form lines (see my Inking Glossary for explanation of my terms). These form lines were previously very dominantly used and were the reason I gave the name to the inking the Sculptural style. I am not going to try to answer this issue now but I am still interested in how the Studio style came into being. As with the art done for Headline, that for Clue Comics does not include the common use of picket fence crosshatching or shoulder blots. However as previously seen in Headline, abstract shadow arches, another technique of the Studio style, begins to appear more frequently. A good example is the splash shown above. Another Studio style technique is the use of drop strings and that mannerism also begins to become more common.

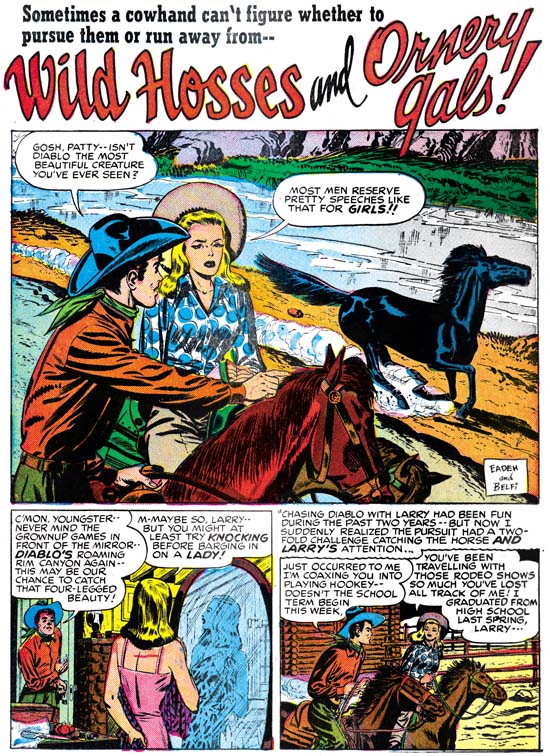

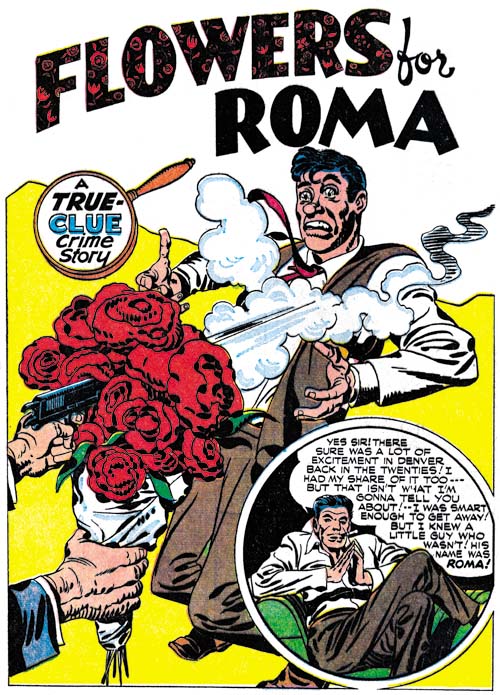

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 3, May 1947) “Flowers for Roma”, art by Jack Kirby

Although the art used for Clue and Headline comics is pretty much the same the panel layouts are not. In my previous chapters on the crime art that Simon and Kirby produced for Prize Comics I noted that circular and semi-circular panels were used at just about the same level as previously in Stuntman and Boy Explorers. On an average this would work out to be about one round panel for every story page. The round panels are completely absent on any of the story pages that Joe and Jack did for Clue. There are two occurrences of circular panels in Clue and they both are restricted to the splash page. The circular panels on the splash page are truly story panels and so must still be considered, but even so there is a clear distinction between the panel layouts for Headline and Clue. I am just not sure what to make of that distinction.

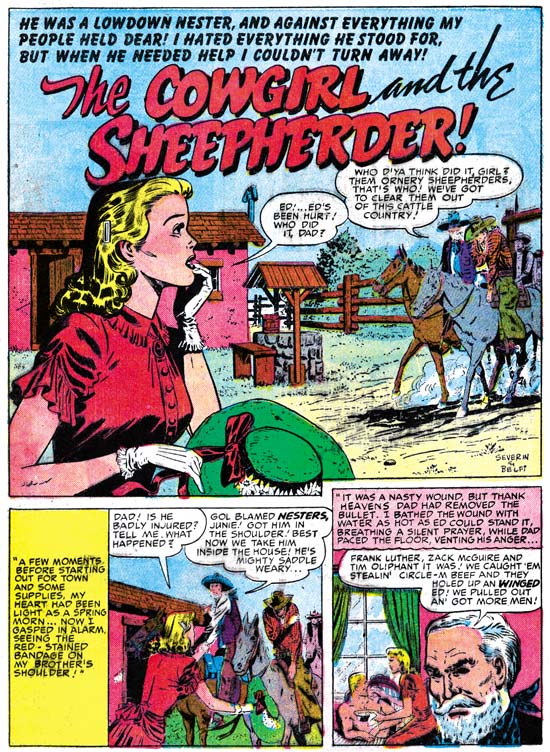

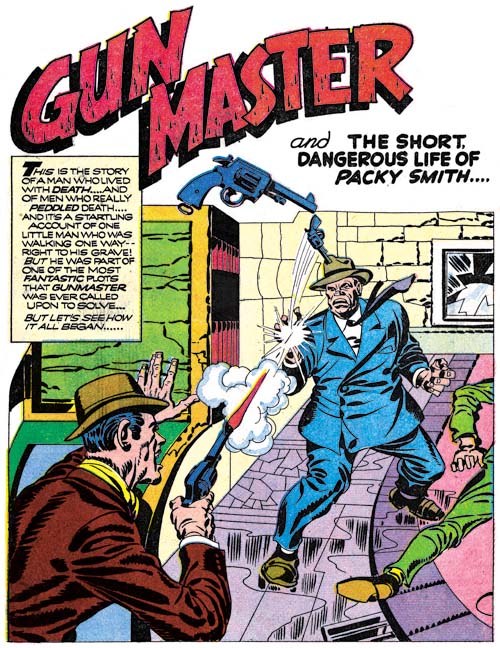

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 2, April 1947) “The Short, Dangerous Life of Packy Smith”, art by Jack Kirby

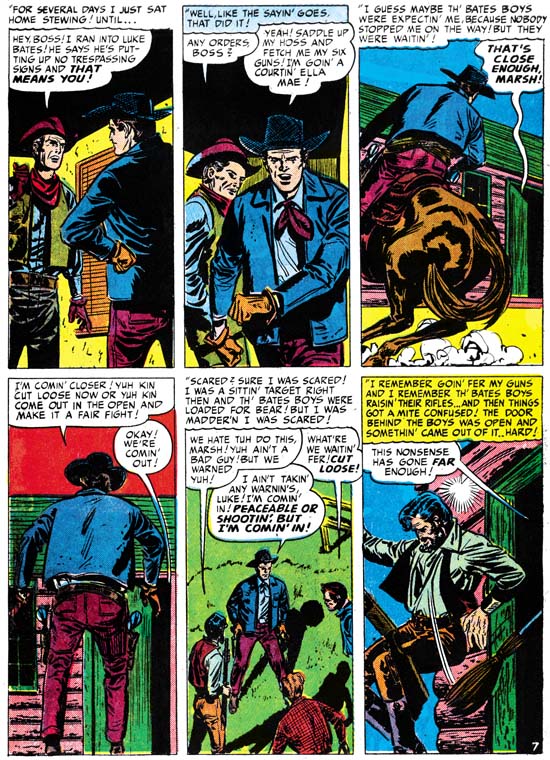

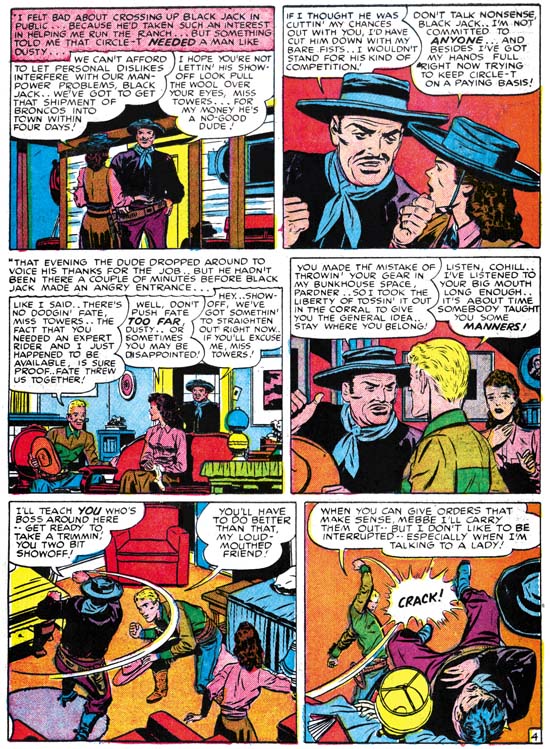

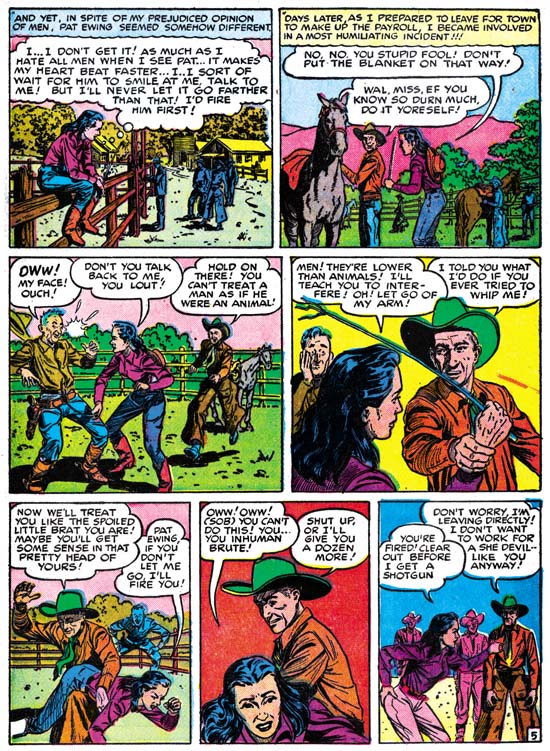

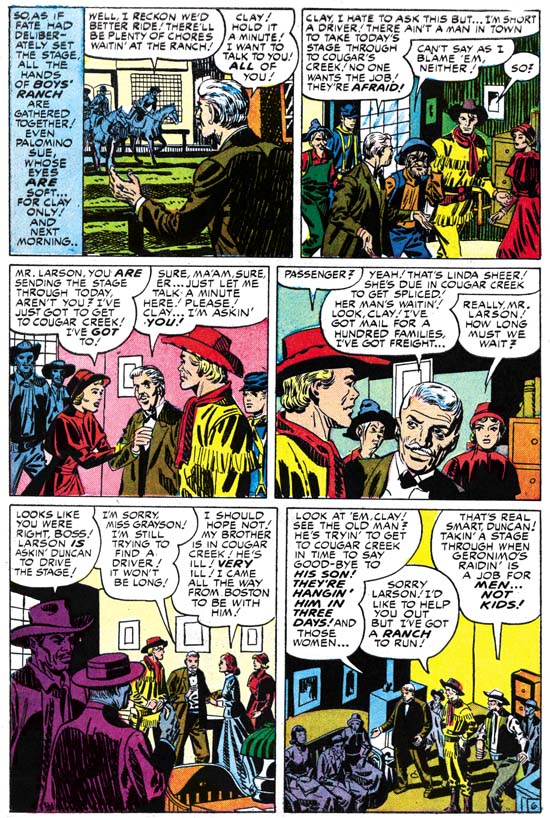

Simon and Kirby’s contribution to Clue Comics was not limited to “true” crime stories. They also had a chance to work on Gun Master as well. Because it was the key feature for Clue Comics it is not surprising that Joe and Jack did not make any serious changes to Gun Master. Gun Master remained an uncanny marksman who continued to receive his direction from the robed Council of Elders. However Simon and Kirby did make one innovation, they tried to provide the feature with a continuing story line while previously all the Gun Master stories had been stand alone units. What Simon and Kirby did was to introduce Packy Smith a man born with “element X” in his body and as the result doomed to an early death. If that were not bad enough it turns out that element X could be used to turn Packy into a human bomb. This results into a manhunt for Packy by not only Gun Master but by the criminal element as well. In the April issue the story ends with Packy Smith disappearance after haven taken a nose dive off a bridge. In the May issue Simon and Kirby continue the tale revealing that Packy had survived the plunge. Even the ending for the second tale was clearly not meant to be the finish as not only does Packy get away again but Gun Master has obtained the phone number to the criminal mastermind behind the manhunt. Unfortunately although Gun Master would make some further appearances, Simon and Kirby never returned to the feature to continue the story. Clearly Joe and Jack were not simply following someone else’s script.

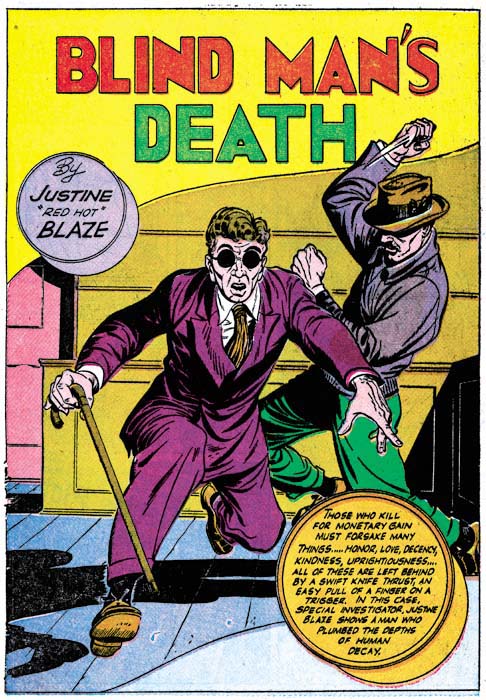

Clue Comics (volume 2, number 2, April 1947) “The Finger Man”, art by Carmine Infantino and Bernard Sachs

As previously discussed there were a number of continuing features in Clue Comics. Simon and Kirby would produce most of the remaining “true” crime stories, but not all. “The Finger Man” is one such example. Fortunately it is signed otherwise I am not sure I would have recognized Infantino’s work. Besides his silver age comics I am most familiar with the Charlie Chan Comics that Carmine drew for Simon and Kirby in 1948 and early 1949. Despite the fact that Charlie Chan was done only a little over a year later, the style Carmine used was very different then the one shown here in “The Finger Man”. It would seem that Infantino adopted a Kirby influenced style just for the work on Charlie Chan. Carmine is an excellent artist and it would be interesting how his style evolved over the years. Unfortunately Infantino only worked for Simon and Kirby that once and so my knowledge of his art is otherwise limited to occasional pieces such as this. In “The Finger Man” Carmine is inked by Bernard Sachs. Sachs was a commonly used inker at Hillman at this time and he also did some pencil work.

Like the initial Headline art that Simon and Kirby did for Prize, the duo did not provide signatures on any of the work they did on Clue. The only work for Hillman that they signed was for My Date and a single cover for Western Fighters. As I mentioned in the last chapter it was very untypical for Simon and Kirby to leave out their signature on so much work. My Date was probably their idea and nothing like it was being produced at Prize so it is not surprising that they would sign work in that title. Otherwise Joe and Jack probably did not want to make it too obvious that they were providing work for two different publishers at the same time.

My conclusion after reviewing the material is that the drifting of Clue Comics into a more truly crime comic had little, if anything, to do with Simon and Kirby. But S&K’s influence on the title seemed to increase as time went on. The May issue of Clue Comics (v. 2, n 4) was the last before the title was renamed into Real Clue Crime Comics. This was more then just a name change but that will be covered in my next chapter.

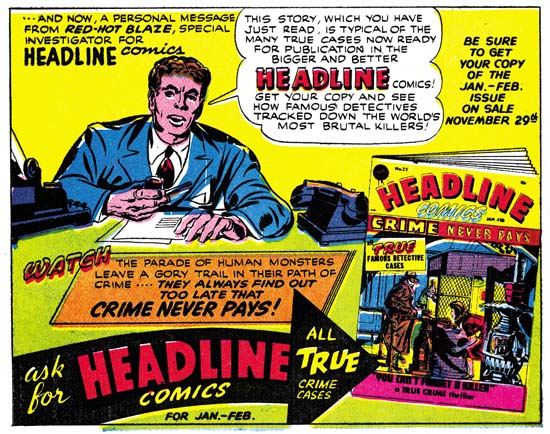

Chapter 1, Promoting Crime

Chapter 2, A Revitalized Title

Chapter 4, Crime Gets Real

Chapter 5, Making a Commitment

Chapter 6, Forgotten Artists

Chapter 7, A Studio With Many Artists

Chapter 8, The Chinese Detective

Chapter 9, Not The Same

Chapter 10, The Master and His Protege

Chapter 11, The New Team