In 1934 Captain Joseph Patterson offered Milton Caniff the opportunity to create an adventure strip for syndication. Milton had been on salary working for Associated Press, now he would have a share in the profits his strip would generate. But the strip would not truly be his, as was customary at the time Caniff’s creation would actually be owned by Patterson’s syndicate. The strip was named Terry and the Pirates and it became very popular. Milton had free reign, Patterson respected Caniff’s capability and never exercised any editorial control of the comic strip. That is until Milt introduced the Japanese into his story. Caniff wanted Terry and the Pirates to be realistic. Since the story was located in China, after their invasion of that country it made sense for the Japanese to be a part of the story. Captain Patterson however was an isolationist and he ordered Milton to keep the Japanese out of Terry and the Pirates. Since Patterson’s syndicate was the true owner of Terry, Milton had no choice but to submit to this demand. Patterson’s isolationism, like that of many other Americans, would change a very short time later when Japan attached Pearl Harbor. Caniff no longer faced opposition and the real war would enter Terry and the Pirates.

Editorial interference was not the only problem Caniff faced due to his contractual arrangement for Terry and the Pirates. Milton had phlebitis, a condition where at any time a blood clot might form in his leg and then travel to another part of his body resulting in death. With care this might never happen but it was a possibility that could neither be eliminated nor predicted. There was little chance that Patterson would ever remove Caniff as the artist for Terry and the Pirates, but if Milt died all money from the strip would stop, leaving his wife without any source of income.

Terry and the Pirates was a very successful strip, in no small part due to Caniff’s injection of the real world into the story. Polls indicated Terry’s popularity, but they showed that the strip was not the most popular one. However the polls did not tell the full story and there is little doubt that Milton Caniff was the most followed cartoonist during the war years. This was due not only to Terry and the Pirates but also because of Male Call, a strip that Caniff produced for the armed service newspapers. Male Call was a bit too risque for family newspapers but was recognized as a great morale boaster for the men in our military forces.

After the war Caniff was approached by Marshall Field III who asked what sort of deal would entice him to leave Terry and the Pirates and create a new strip? Milton was very happy with his present financial status but questions of editorial control and security for his wife were still concerns. Caniff’s reply to Marshall’s question was simple, Milt wanted complete ownership of the strip. This was an unheard of demand, but Field did not hesitate to accept it. A deal was quickly reached that would be very rewarding for Caniff. Unfortunately Caniff still had nearly two years to go on his contract with Patterson. While that contract was in effect anything Caniff drew could be considered the property of Patterson. This left Field in the unusual position of trying to get newspapers to sign on without anything to show, not even the subject or name of the new strip. Based solely on Milton Caniff’s reputation, Field’s sales force managed to sign up 144 newspapers. All of this brought a lot of media attention and public interest as to what Caniff’s new strip would be like.

Joe Simon and Jack Kirby had special reason to be reminded of Milton Caniff. Shortly after the war Simon and Kirby had produced some new comics (Stuntman and Boy Explorers) for Harvey comics. These new titles suffered a quick death due to the glut of comics that were released once wartime paper restrictions had been lifted. With so much to choose from newsstands would provide rack space only for those titles with good recognition, new comics were out of luck. Harvey felt he had the answer to that problem, create a new title using a popular syndication strip. Not only did this provide instant recognition, only the cover art needed be made and the strips rearranged to fit the comic book format. This had been a successful approach for Harvey in the past with Joe Palooka and he now tried it with Terry and the Pirates. Joe and Jack would surely be aware of this not only because they were good friends with Al Harvey, but also because one of their Boy Explorers stories (“The Isle Where Women Rule”) would appear in the initial issues of Terry and the Pirates.

Caniff’s Steve Canyon premier in the weekly papers starting on January 13, 1947. Milt’s opened with an unusual gambit, the title character never makes an appearance throughout the entire week. The most we get to see of him is a portrait photograph that is handled by some of the story characters. The week’s story shows the representative of a wealthy and beautiful businesswoman attempting to meet Steve Canyon to hire him for an unspecified job. Canyon finally makes an appearance in the following Sunday strip, but for the first half of it we do not get to see his face. For Sunday we find Steve walking to his office. Upon arrival he is informed about the representative’s visit. Steve telephones him and effectively declines the job. Only an artist assured of his audience and his own talent would introduce a strip with such a slow buildup. But Caniff is the consummate strip artist and the introduction is anything but boring. It builds on the audience’s anticipation while providing an introduction to all the principals of the first story arc. The reader also learns that Canyon has an air transport business that is not very financially successful. The existing business acumen seems to be provided by his young secretary, a beautiful south Pacific woman.

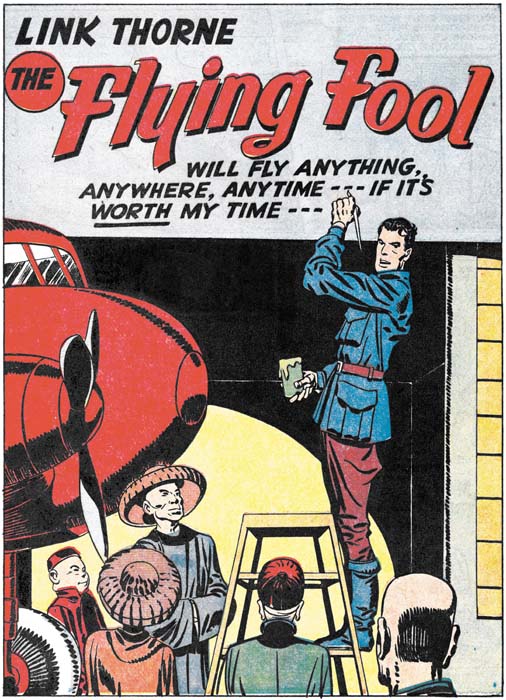

Airboy Comics v4 #5 (June 1947) “The Flying Fool”, art by Jack Kirby

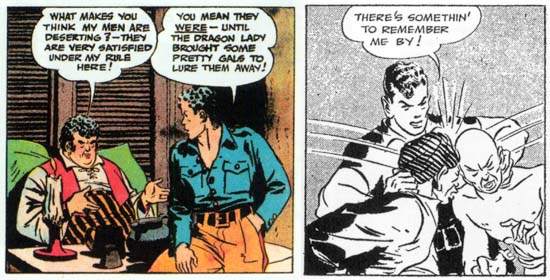

Simon and Kirby would debut a new feature in Hillman Publication’s June issue of Airboy Comics called the Flying Fool. The introduction begins with the arrival of some shady Chinese characters to the office of a flight service. They tell the beautiful Chinese secretary that they are seeking her boss for a business proposition. That boss, Link Thorne, arrives to find that the proposition is that a rival, Riot O’Hara, wants to take over Thorne’s business. A fight ensues and although he is out numbered, Link Thorne is the winner. Furious Link decides to pay Riot O’Hara an unannounced visit only to discover that she is a beautiful woman. The parallels of this story to Caniff’s Steve Canyon are pretty apparent. Both feature a talented pilot with an independent streak who has a small and not very successful air transport business. Both heroes’ independence nature leads them to reject a proposal from beautiful but ruthless businesswomen. Even the stories have a similar beginning where the businesswomens’ representatives arrive at the air transport offices but do not initially find the owners. There are differences, while Steve Canyon’s office is in an American city Link’s is in China. But that difference is not that significant because Caniff’s previous strip also took place in China. More important is the initial confrontation, while Steve Canyon verbally duels with the businesswoman’s representative over the phone, Link Thorne’s reaction is a typical Kirby slugfest. Also Simon and Kirby use the secretary to provide a taste of comedy into the story. Caniff was not blind to the usefulness of a sidekick to provide a comic element, he had such a character in Terry and the Pirates and would introduce one later in Steve Canyon.

The timing of the creation of the Flying Fool is of special interest. Comic cover titles are generally marked two months later then the actual release date, which would mean that the Flying Fool appeared on the newsstands in April. But the actual creation normally starts three to four months earlier; a month for the distribution, a month for printing, leaving one or two months for the art. Since Milton Caniff’s new strip was kept so secret and the Flying Fool story is so clearly derived from Steve Canyon, the S&K story could not have been started before mid January. This would only have left Joe and Jack a week or two to produce the art. It is a short story and Kirby was famous for his speed, however you cannot tell that it was a rush job from the final product. It is as beautiful an example of a Simon and Kirby production as any from that period.

Terry and the Pirates (left panel from April 17, 1936, right panel from December 20, 1936) art by Milton Caniff (both from “The Complete Terry and the Pirates” by IDW Publishing)

Most of Jack Kirby’s inking was done using a brush. This is not particularly unusual as working with a brush was common for comic inkers. It had not always been so, before comic books there were comic strips and initially they were inked largely with a pen. A brush might be used to flood an area with black, but in that case the black was used as a color. The use of a brush for chiaroscuro effects was first introduced in January 1936 by Noel Sickles in his syndication strip Scorchy Smith. Sickles shared his studio with Milton Caniff who quickly recognized the significance of brush work in both adding realism and saving time. Caniff began to adopt the use of a brush in Terry and the Pirates in March. Terry and the Pirates was much more popular then Scorchy Smith and so most comic artists picked up the brush technique from observing Caniff’s work. Caniff’s influence on Kirby is clear from the similarity of the Flying Fool to Steve Canyon, this surely includes art techniques as well. That right panel sure looks like the shoulder blot that Kirby used so often.

The basics of what I have written here were previously covered by Greg Theakston in his Complete Jack Kirby. However I have been able to add detail to that account because of the recent publication of two books. One is “Meanwhile… A Biography of Milton Caniff” by Robert C. Harvey published by Fantagraphics Books. This is a thorough and lengthy book full of information and insight. I am still in the process of reading it but nonetheless I can heartedly recommend it. The other is the first volume of “The Complete Terry and the Pirates, 1934 – 1936” by IDW Publishing. This is a beautiful volume with excellent reproductions. In fact for me it has become the highest standard for comic reproduction. The colored Sunday strips are nicely cleaned up scans. For reasons that I do not understand, most publishers recolor the work when they reprint it. I find the end result very flat, if not down right ugly. The only happy exception to this is the Spirit Archives where Will Eisner carefully specified the paper and color saturation levels. In the case of Terry and the Pirates this is not just a question of aesthetics, Milton Caniff did the color guides himself. His syndication recognized how important his coloring was and had one engraver whose sole responsibility was the Terry Sunday strips. Recoloring this work would have been a sin that IDW wisely avoided.

Hi Harry,

Nice post! But, there is more to the story. 😉 The Flying Fool was not a Simon and Kirby creation, his first appearance was in Airboy Comics Vol4 #8 Sept 1946. The little I have seen of the 3-4 pre-S&K stories show Link Thorne as a post-war flyer with a small freight service in the Orient, just as in the S&K tales. It does seem that Wing Ding, and Riot O’Hara are original to S&K.

So I think you are right that when Joe and Jack came over to Hillman, that they quickly retrofitted the original Flying Fool (by Frank Giacoia) into a Steve Canyon clone. I wonder if they retrofitted the Gunmaster as well, or did they continue that series as originally created?

Yet there was another Flying Fool that preceded both the Giacoia or the Simon/Kirby model.

Over at Harvey Pub. Bob Powell had a recurring character- a war pilot called Chickie Ricks, who showed up as a back-up strip in some titles. In All New Comics #13 Jun 1946, the strip was renamed to “Flyin’ Fool aka Chickie Ricks”, he then appears as a continuing back-up in Joe Palooka, titled simply “Flyin’ Fool”.

I wonder if there was a real pilot who was nicknamed the Flyin’ Fool, who inspired these strips?

Stan

Stan,

Thanks for the previous Flying Fool info. I wonder if their doing the Flying Fool was S&K’s idea or Hillman’s? Simon and Kirby’s run was not much longer then the original one, but I think that may have been due to the better deal S&K arranged with Prize comics. Despite its short run, the S&K Flying Fool is really beautiful work.

I was aware of Bob Powell’s version, but other then its name there really is not much connecting the two. In my younger days I once worked on a small airport, from my experience Flying Fool was an appropriate and obvious nickname for some of the characters associated with flying, with emphasis on the second part of the name.

Harry