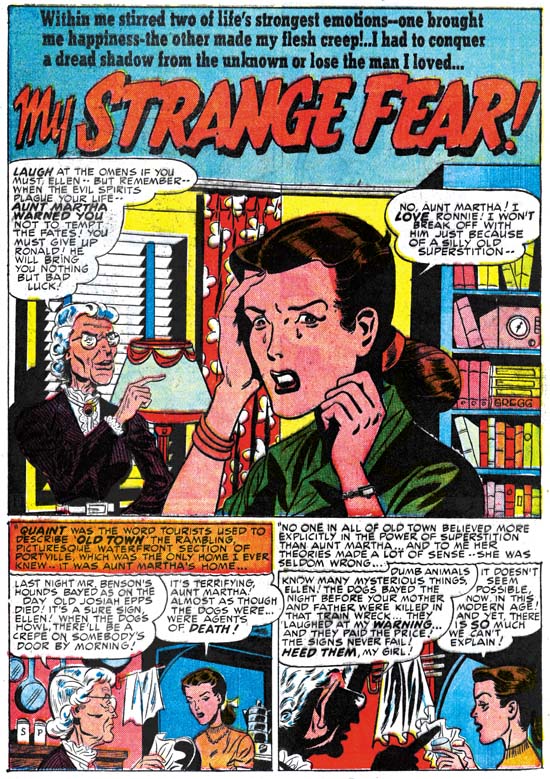

I have long held off discussing Boys’ Ranch since with so much written about that title I feared I would have little new to add. Today Boys’ Ranch is probably one of the most popular Simon and Kirby post-war creations. There is good reason for this modern esteem as the title has much to commend it; action, humor and lots of Kirby. Nothing has done more to keep the Simon and Kirby brand name alive as Marvel’s Boys’ Ranch and Fighting American reprint volumes. Although published in 1992 these volumes are still readily available in the resale market at reasonable prices. Of the two, the Boys’ Ranch volume most accurately reflects the original published comic books. Harvey’s reprinting of Boys’ Ranch stories occurred prior to the establishment of the Comic Code and so the art and stories did not suffer from censorial abuse. I have examined the comics and the Marvel reprint side by side and so far the only changes I have detected were a very few coloring alterations. Unfortunately Harvey reprinted Fighting American during the Comic Code’s reign and the Marvel volume makes use of Harvey’s reprinted version. Mark Evanier’s “Jack Kirby, King of Comics” provides an example from the Fighting American of the removal of an ice pick from one panel leaving an attack without a weapon. All is not completely well for the Marvel reprint volume as a few pages of general interest fillers have been dropped. These single page graphic articles were not drawn by Kirby so many readers will not have lost much. The more hardcore Kirby fans will regret the absence of the text stories some of which had included illustrations by Jack.

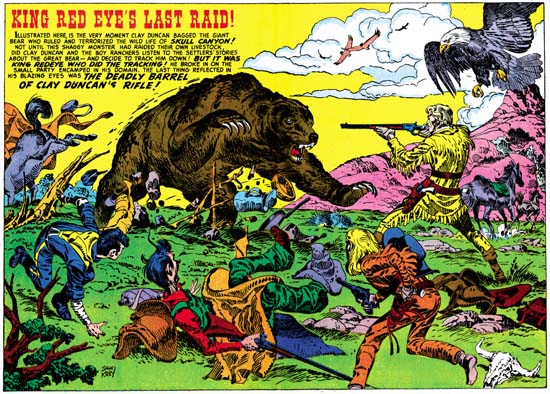

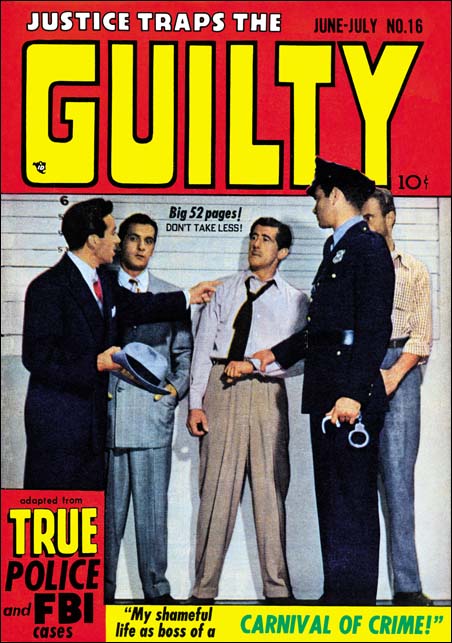

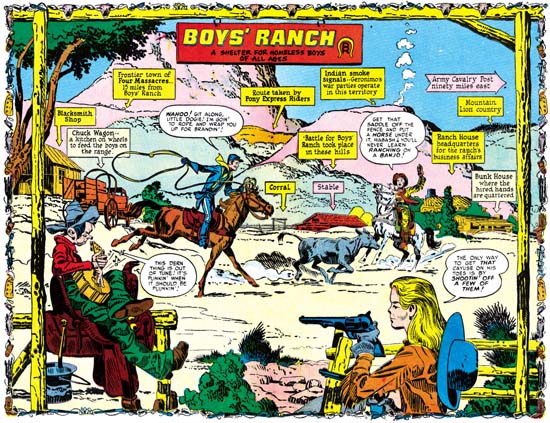

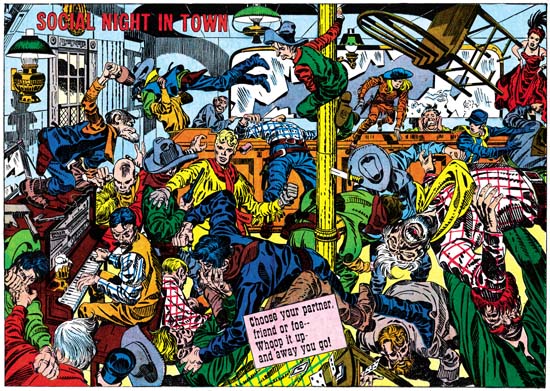

Boys’ Ranch #2 (December 1950) pinup, art by Jack Kirby

I have not completely ignored Boys’ Ranch in the Simon and Kirby Blog. Recently I have included the double page pinups from this title in a couple of chapters of my serial post “The Wide Angle Scream” (here and here). The use of pinups, both single and double page, was something new for Simon and Kirby. Each issue of Boys’ Ranch would have a single page pinup at the beginning of the book along with the centerfold pinup. Such extensive use of pinups would not be repeated in any other Simon and Kirby production. The pinups are not only numerous, they are also consistently of high quality. I would be hard pressed to pick the best one. I do want to provide an example and so choose one that provides the best portrait of the main cast of characters. Boys’ Ranch is not just a western, it is also belongs to the boy gang genre so favored by Simon and Kirby. There are significant parallels between the Boys’ Ranch gang and say the Newsboy Legion. Most S&K gangs have one adult member to act as a type of guardian. Clay Duncan does that part and although he lacks a secret identity he does have his own unique origin. One constant in S&K boy gangs is a handsome character that the readers can relate to; in Boys’ Ranch this is Dandy. There is always a gang member to take on the humorous aspects. Often this individual has some regional identification. This role is taken by Wabash who plays a southern hillbilly. The other two main characters are unusual members of this particular gang. Wee Willie Weehawken (I guess New Jersey seemed to be out west to New Yorkers Joe and Jack) was different in being a second humorous member and in being an adult although otherwise treated as another gang member. The most unique member of them all was Angel. Most Simon and Kirby kid gangs included one intellectual but I guess Simon and Kirby felt that such a character would be out of place out west. Instead Angle is sharp shooter with a bit of a temper. The 50s were a time with great emphasis on conformity and Angel’s long hair was definitely a distinction. Not included in the splash was another cast character, Palomino. Her place at Boys’ Ranch was often obscured but she would play important rolls. One was to help shape Clay’s image. Her obvious love for Clay was used to promote him as a hero figure. This also allowed Clay to be disinclined to actively return her affections thereby showing to his young readership that he as a real man’s man (at least by the criteria of youthful readers at that time). When Clay and the boys would go off to some adventure Clay would pointed tell Palomino that she could not come as it was too dangerous for girls. She would reluctantly agree only to following them anyway and save the day at some critical point. Action heroines were not unheard of but generally not used by Simon and Kirby whose women normally play the roll of victims. Palomino is a refreshing exception. Another minor player in Boys’ Ranch is the diminutive and silent Indian, Happy Boy.

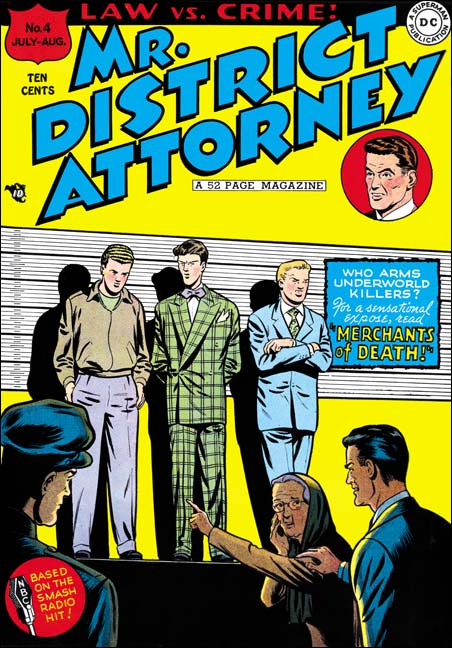

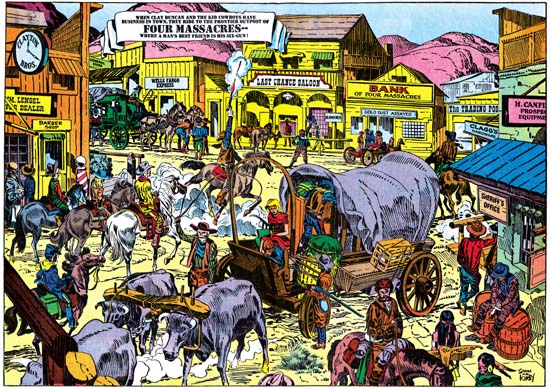

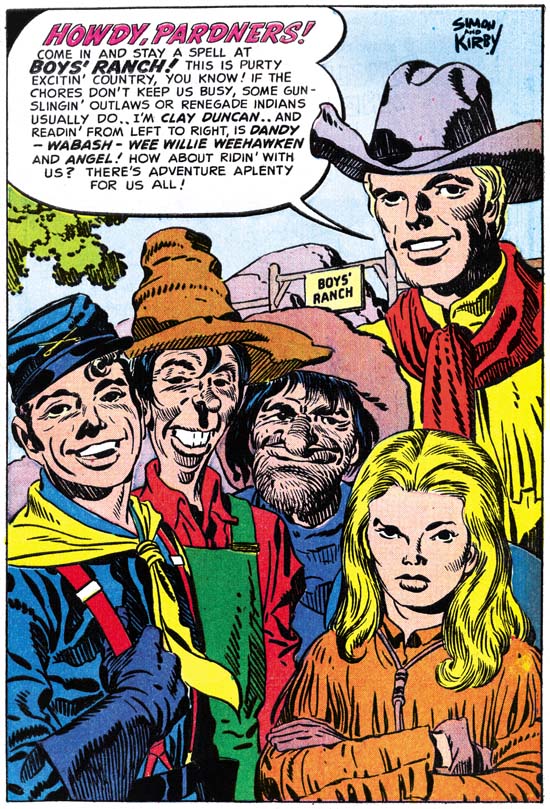

Boys’ Ranch #2 (December 1950) “Lead Will Fly At Sunset”, art by Jack Kirby

Not only did Boys’ Ranch include exceptional pinups, the splash pages are among the best that Jack Kirby did and that is saying a lot. Most of them are full page splashes filled with excitement. However the most unusual splash that Kirby did, not just for Boys’ Ranch but for any Simon and Kirby production, was certainly the one for “Lead Will Fly at Sunset”. Not only does it have no action, it does not even have any characters at all. That is Boys’ Ranch we see below from a distance but there is only the caption to confirm that. What we are provided with is nothing more then a landscape. Well that is a little misleading as this was drawn by Jack Kirby who shows here that he can embody a landscape with interest as well. Partly this is due to the unusual perspective Jack has depicted. In the foreground a steep trail descends to a panoramic vista. The nearby terrain is so rugged that only a few twisted trees have managed to cling to the rocks. With the extensive view it is easy to overlook the most significant inhabitant, a coyote on our left descending via the trail.

Boys’ Ranch #1 (October 1950) “The Man Who Hated Boys” page 14, art by Jack Kirby

When Simon and Kirby created Captain America their origin story was only 8 pages long. Only one other Captain America story from the first issue was shorter while the rest were substantially longer. The Red Skull story had twice as many pages as the origin story. The origin was clearly something to get over with as quickly as possible so as to get into the adventures. With the work that Simon and Kirby did for DC and Harvey (Stuntman and Boy Explorers) the origin story was a much more successful story by itself. None of the other Joe and Jack’s origin stories compares with what they did for Boys’ Ranch. It is not just that “The Man Who Hated Boys” is 17 pages long, it is also how S&K weaved the story. Unlike the first Newsboy Legion story, the members of the boy gang are not introduced as a unit. The reader is first shown Dandy and Wabash meeting while Clay Duncan and Angel make their appearances later. All the character introductions are all mixed in with typical Simon and Kirby action. As for example page 14 shown above. Previously Clay, Dandy and Wabash had been pinned down by Indians. At the start of this page we find Angle arriving on horse back with some other reinforcements. Other creators might be satisfied with having the arriving party drive off the Indians, but not Simon and Kirby. We find in the last panel the fight has become the way Kirby preferred, up close and personal. Let me digress for a moment to point out how in the first panel only the mouth and knee of the closest horse is depicted. Kirby would use the same device years later in Bullseye #7 (August 1955). “The Man Who Hated Boys” was a justifiably lengthy introduction but even it does not present all the cast of characters. “Meet Wee Willie Weehawken” would introduce that character and other stories would bring in Palomino and Happy Boy. There would also be a separate origin story for Clay Duncan. Never before had Simon and Kirby invested so much in the backgrounds for the characters of a feature. I am sure this is one of the characteristics that make Boys’ Ranch so appealing for today’s reader.

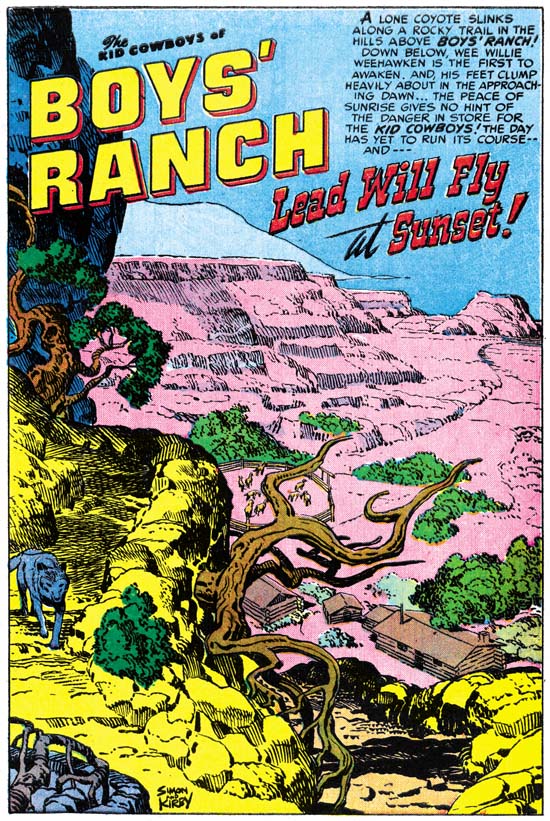

Boys’ Ranch #3 (February 1951) “Mother Delilah”, art by Jack Kirby

If a poll was conducted on what was the best Simon and Kirby story ever, I have little doubt that “Mother Delilah” would be chosen by a wide margin. It certainly deserves such a distinction. Jack Kirby’s pencils are superb and the inking is consistently both sensitive and powerful. The writing is just exceptional and was given plenty of space to fully accomplish its plot and theme (at 20 pages it is the longest Boys’ Ranch story). The theme, well it is literally biblical in nature. The characters and their motivations have a complexity that is rarely seen in comic books even today.

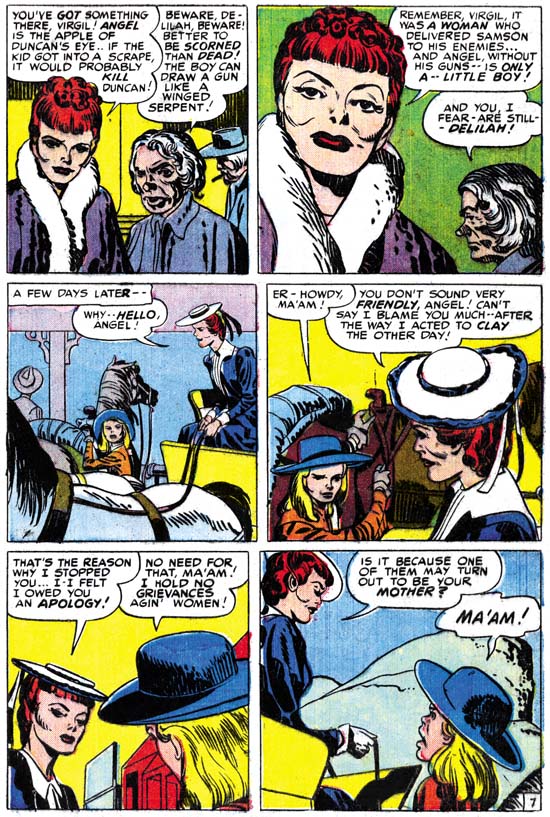

Boys’ Ranch #3 (February 1951) “Mother Delilah” page 7, art by Jack Kirby

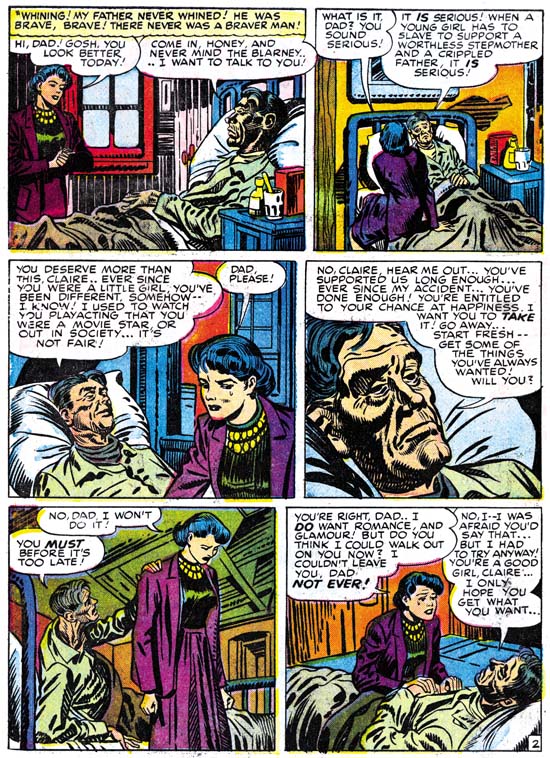

Clay’s rejection of the advances of the saloon girl Delilah leads her to a vow of vengeance. It is through Angel that Delilah seeks to get her revenge. Angel, the story’s main protagonist, is shown to be more then a sharp-shooter with a temper. His bravado is depicted as hiding a longing for a family he has long lost. Even at this level “Mother Delilah” offers more then most comic book stories. However the story goes on to show Delilah as torn between here need to strike back at Clay Duncan and her horror at what this was leading her to do to Angel.

Boys’ Ranch #3 (February 1951) “Mother Delilah” page 2, art by Jack Kirby

Angel and Delilah could have been enough for the story, but the writer choose to include some other cast members as well. There is one, Curley Yager, whose own villainy acts as a foil to that shown by Delilah. Who is the most evil? Curley who, without any thought, treats anyone weaker then himself as a target for his assaults? Or Delilah who realizes the evil she will inflict on Angel but proceeds anyway? Delilah’s self-sacrifice at the story’s end provides the answer as she receives a redemption that Curley could never achieve.

My favorite character plays a minor part in the plot but is of great importance to the story nonetheless; it is Virgil Underwood. His name suggests the classics of Imperial Rome but the part he plays is that of the chorus from Greek tragedy. He is always there to reflect on the action of others.

Boys’ Ranch #3 (February 1951) “Mother Delilah” page 15, art by Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby always thought of himself as primarily a story teller. For many fans his greatest works were the many brawls that he staged. It is true that Kirby was the master of the action sequence. However what amazes me time and time again is how Kirby could handle other types of story lines. Angel, shorn of both hair and pistols, encounters a crowd previously fearful of his sharp-shooter talents. The treatment he receives initially is meant more to humiliate him then to cause bodily harm. Yet before the harassment of Angel goes even further it is suddenly terminated. At first all that is seen are firing guns but that panel is followed by one showing the quick departure of the mob and the arrival of Wabash, Dandy and Clay. The page ends with Dandy and Wabash in the foreground with their backs to the shattered Angel and the comforting Clay. Dandy and Wabash mean to avoid Angel loosing more face then he all ready has, while sheltering him from the views of others, including the readers. It is a very poignant end to the sequence. Who, other then Jack Kirby, ever presented pages like this one?

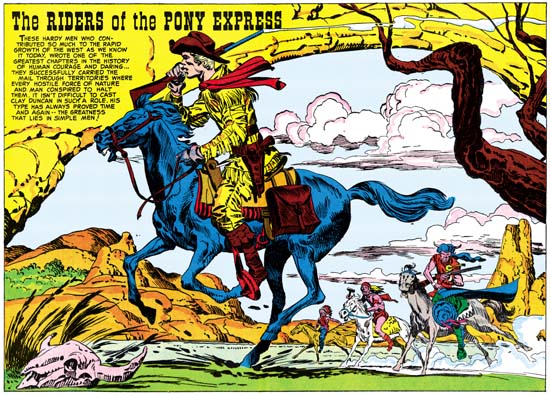

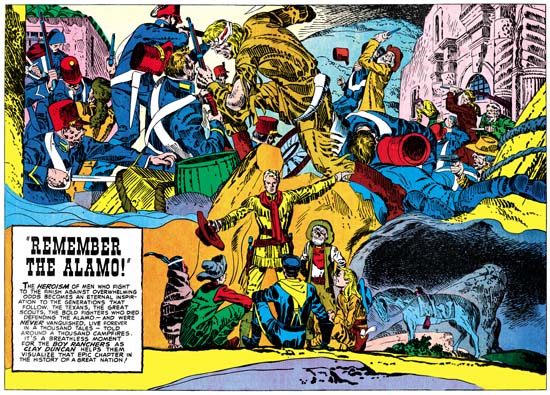

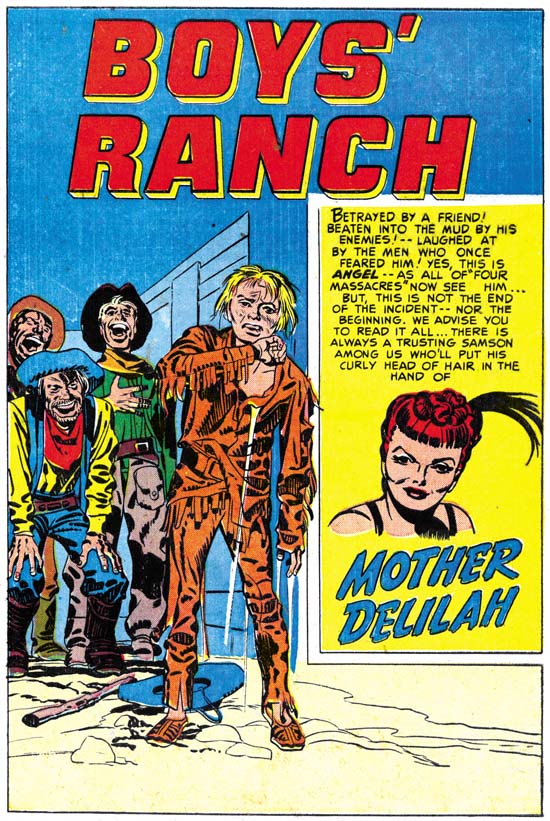

Boys’ Ranch #3 (February 1951) “I’ll Fight You for Lucy”, art by Mort Meskin

For some few exceptions, the first three issues of Boys’ Ranch is all Kirby art. One departure is the single pages about western subjects. These are pages such as how to make moccasins, how to spin a rope or how to ride a horse. Some art dealers claim these were done by Mort Meskin using Kirby layouts. I agree that Meskin did many of them but I doubt very much Jack had anything to do with it. The art for all of them is rather stiff and I suspect are based on some photographs or illustrations. There is also a short section in Boys’ Ranch #1, “Introducing the Kid Cowboys”, that was clearly drawn and inked by Mort Meskin. The most important exception to the all Kirby nature of issues 1 to 3 is “I’ll Fight You for Lucy”. This story is usually credited as Kirby pencils and Meskin inks. There is no question that Meskin did the inking, but I find the layouts and pencils all look like Mort’s work. It is interesting that this is the only Boys’ Ranch story that does not begin with a full page splash. The splash panel is also unusual in how the characters are all placed together in a compact group on the left side. This would have been an unusually arrangement for Kirby who usually composed his figures to spread out and occupy all available space.

Boys’ Ranch #3 (February 1951) “I’ll Fight You for Lucy” page 5, art by Mort Meskin

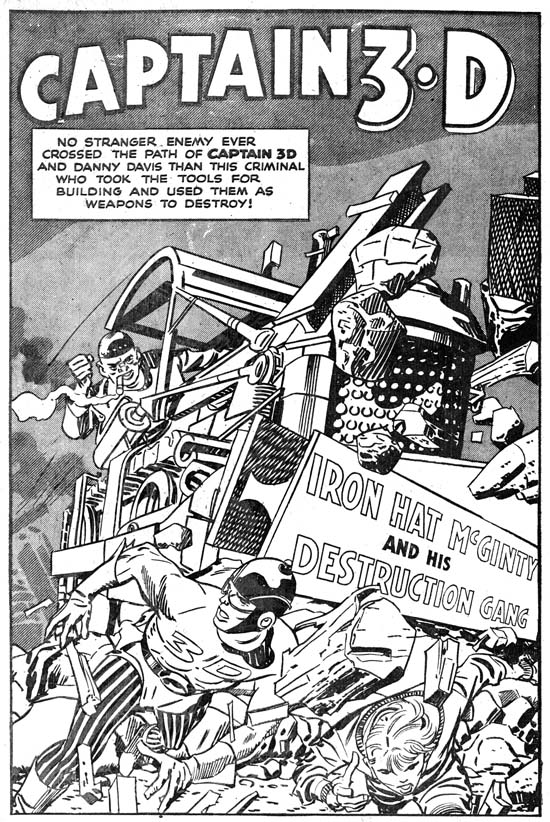

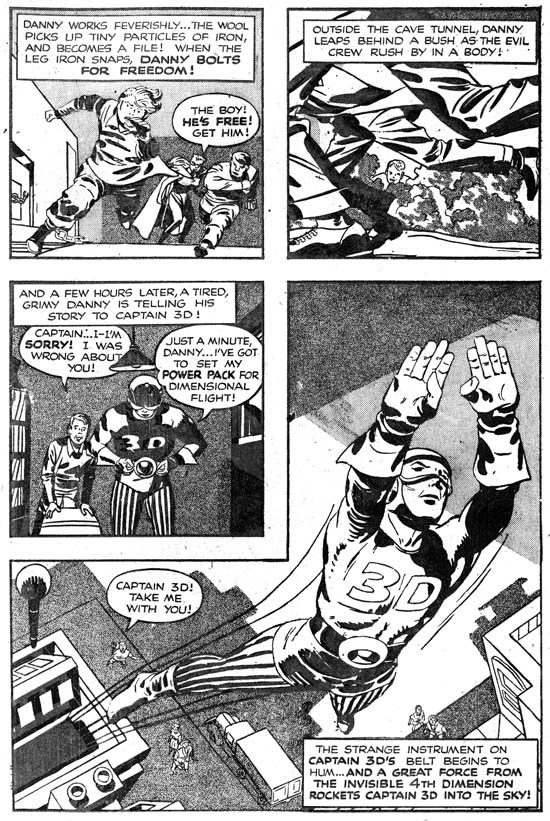

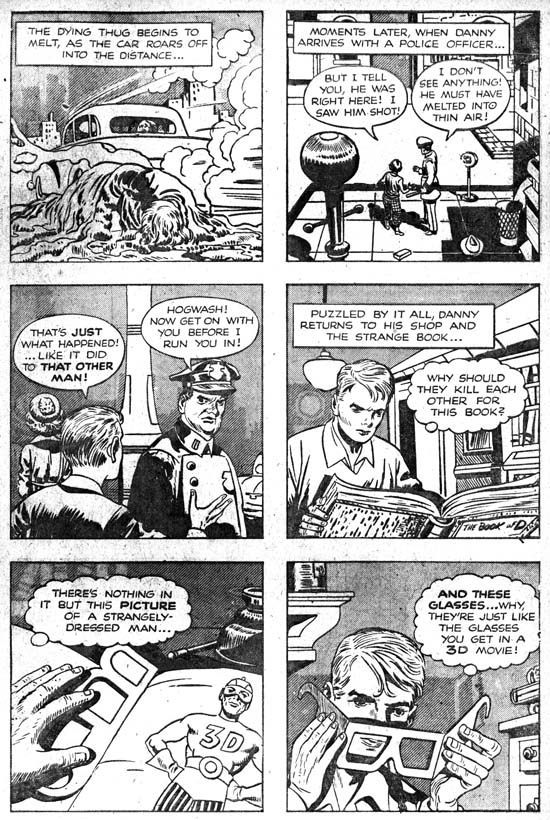

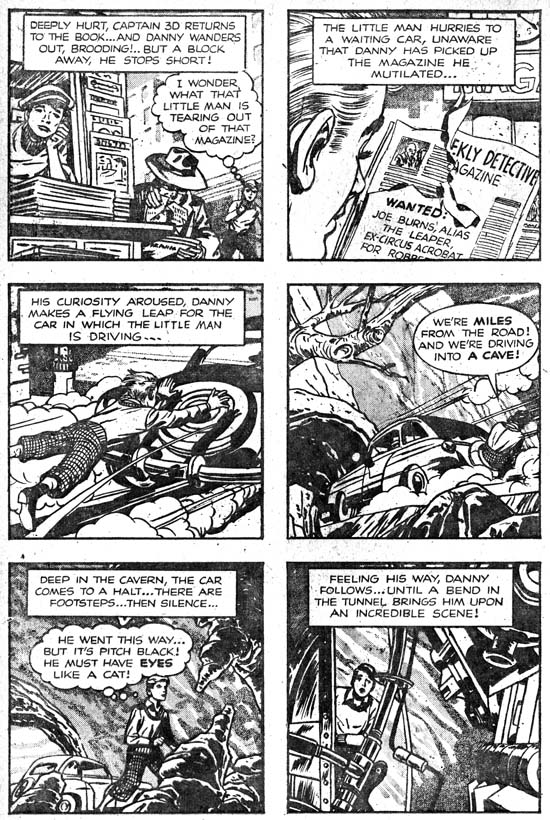

Perhaps the most convincing evidence that this story was not drawn or even laid out by Jack Kirby is the fight scenes. Kirby was justly famous for his slug-fests but the fight from “I’ll Fight You for Lucy” (see above) does not show Jack’s characteristic style. For the later part of his career Mort Meskin did not draw much hero genre comics and so did not do many fight scenes. There are some brawls in the unpublished Captain 3-D #2 story but unfortunately the one image I used in my post about that story is not the best match for the fight from “I’ll Fight You for Lucy”. Better comparisons can be found by turning to work that Mort did earlier. Compare the Boys’ Ranch page with a page from Black Terror #23 (see below) by the team of Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin. Usually when comic art has two signatures the first often indicates the penciler and the last the inker. The division of labor used by Robinson and Meskin seems to have been more complicated. (As, of course, it was for Simon and Kirby)

Black Terror #23 (June 1948) “Danger In The Air” page 3, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

The modus operandi for Simon and Kirby seems to have been to heavily use Kirby in the initial issues for a title and afterwards have other artists do more of the work. This was the case for Boys’ Ranch where the final three issues use Kirby in some interesting variations. That will be the subject of next weeks post.