(Young Romance #5 – #8)

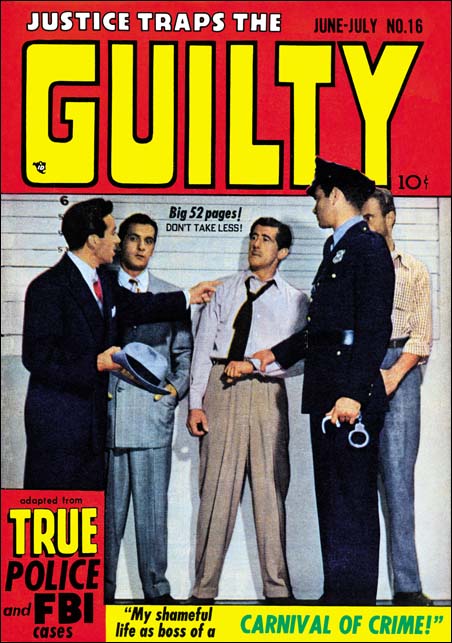

In this chapter I will be writing about the next four issues of Young Romance (#5 to #8). For the most part this set is a continuation of the earlier issues. The main artists were same; Jack Kirby, Bill Draut and the team of Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin. A couple of minor artists that appeared in issues #1 and #2 do not reappear, but a new one would have a contribution which I will discuss in more detail below. Young Romance is still on a bimonthly schedule. This is surprising because by now S&K and Prize were surely aware that they had a hit. When the crime genre Headline (starting with issue #23, March 1947) was a success Simon and Kirby launched Justice Traps the Guilty for Prize seven months later. Yet after over a year they neither made Young Romance a monthly nor created another title. Other publishers had not failed to notice; based on “All the Romance Comics Ever Published (?)” romance titles began to appear published by Fox (My Life #4, September 1948), Timely (My Romance #1, September), and Fawcett (Sweethearts #68, October). Perhaps Prize along with Simon and Kirby were surprised at their own success and fearful that it was just a fad.

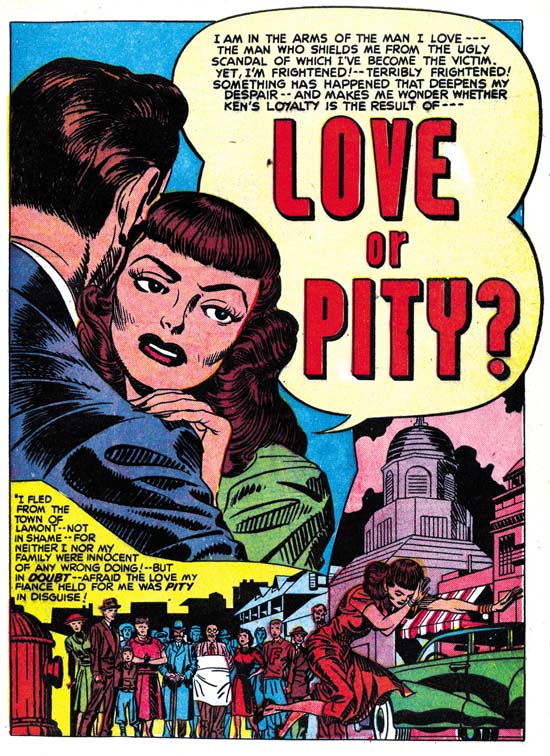

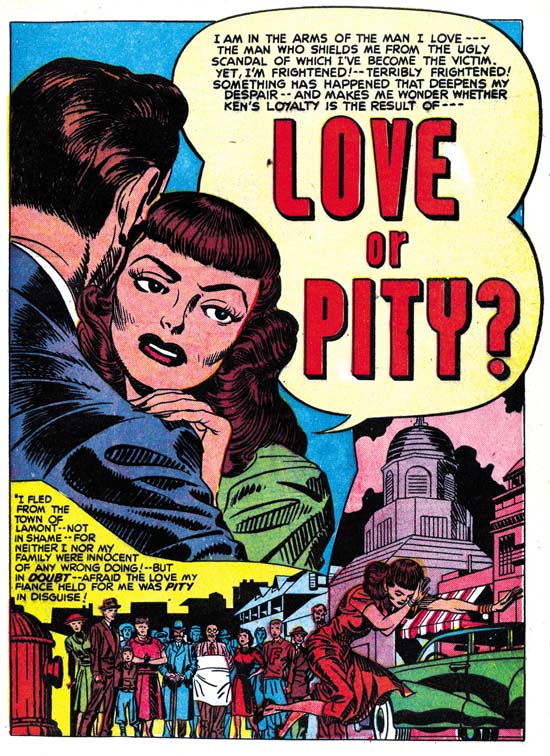

Young Romance #8 (November 1948) “Love or Pity”, art by Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby continued to be the most prominent artist for Young Romance. Kirby did nine out of the twenty stories in these four issues, or 97 out of 177 pages. It may have been even more since as I will discuss below a tenth story may also have been penciled by Jack. Kirby would continue to create the first story in the comic. This lead story would remain the longest story in the comic with thirteen or fourteen pages while other stories would have at most nine pages. The design of the lead story splash page would continue to have a character’s speech balloon used as the title caption. I particularly like the splash for “Love or Pity”. The design is done quite well with a close-up of a couple dominating the page and another section enacting a little scene like some sort of tableau. We have seen this emphasis in design for some of Simon and Kirby’s double page splashes, but it is also to be found in a number of the smaller splashes drawn by Kirby in Young Romance. In the depiction of the large couple we only get to see the face of the woman, the man’s face and his emotions remain a mystery. The woman arches her left eyebrow, looks askance and her hand’s placement on the man’s shoulder seems tentative. All this makes her appear apprehensive and her attempt to dispel her concerns by moving closer into the man’s embrace seems to have failed. From the title caption we learn why, she is uncertain about the man’s true feelings. Many have described Kirby’s woman as not being truly beautiful but it is a criticism I do not share. I find the woman in this splash attractive enough and, more importantly, very human. While some other artists might have been able to make the woman appear even more beautiful I do not know any that are able to invest them with the same sensitivity that Kirby has. Jack does not draw Barbie dolls but rather woman whose appearance reflects their personality and emotions. I find that makes Kirby’s woman truly beautiful indeed.

The second section of the splash depicts a crowd looking disapprovingly on as the woman runs away in shame. Jack has chosen a low viewing angle so that the woman towers over the background crowd giving drama to the scene. The woman’s pose is rather unusual; she looks more like she is tripping and about to fall. Not an inappropriate metaphor for her descent into scandal. The second section is well done but its impact suffers from its diminished size. Envision this section enlarged and expanded toward the right and you can imagine what a double page romance splash might have looked like had Simon and Kirby ever done one. It is too bad they never did.

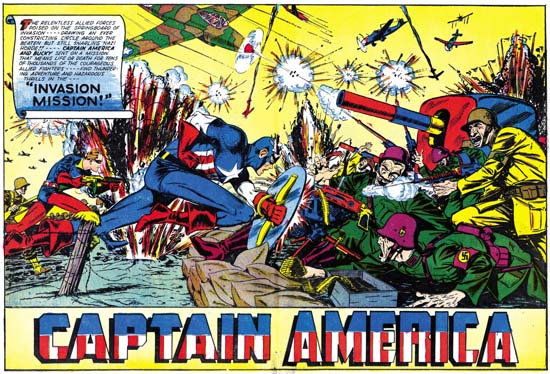

Young Romance #6 (July 1948) “Disgrace”, art by Jack Kirby

One change that seemed to have taken place from the earlier issues of Young Romance was that action no longer appeared quite as commonly in Jack Kirby’s romance stories. Not that action disappeared completely, it would always show up in more Kirby romance stories then it does in those by any of the other studio artists. “Disgrace” is a case in point. If I had to pick one Kirby romance story most likely to satisfy the general Kirby readership, this would be the one. The heroine feels trapped in a coal mining town which she detests for the violence its inhabitants so frequently adopt. Her brother has managed to escape the town but she is dismayed at his career as a prize fighter and his particularly brutal nature. She falls in love with a man only to discover that he also is a professional boxer. She cannot accept more violence in her life so she breaks it off. Later she finds to her horror that her brother and former love are scheduled to meet in the arena. Where does her loyalty lie, with her violent brother or the man she still loves? Jack Kirby is justly famous for his depiction of a punch and the fight in this story is a pure slugfest.

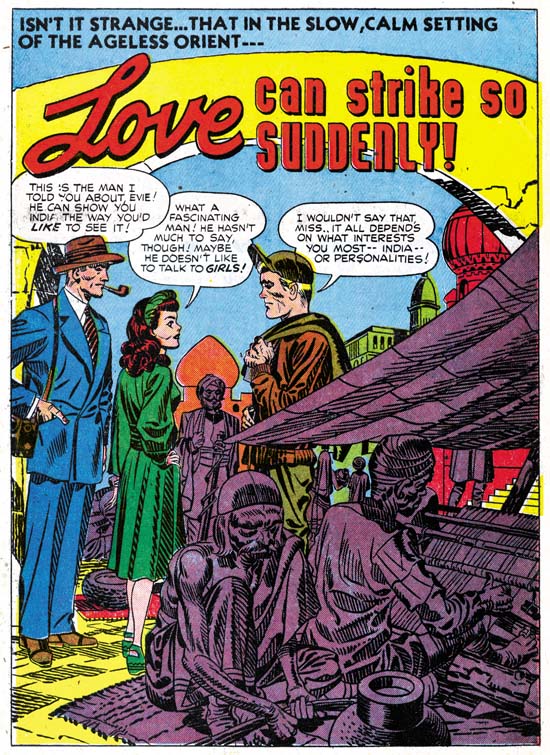

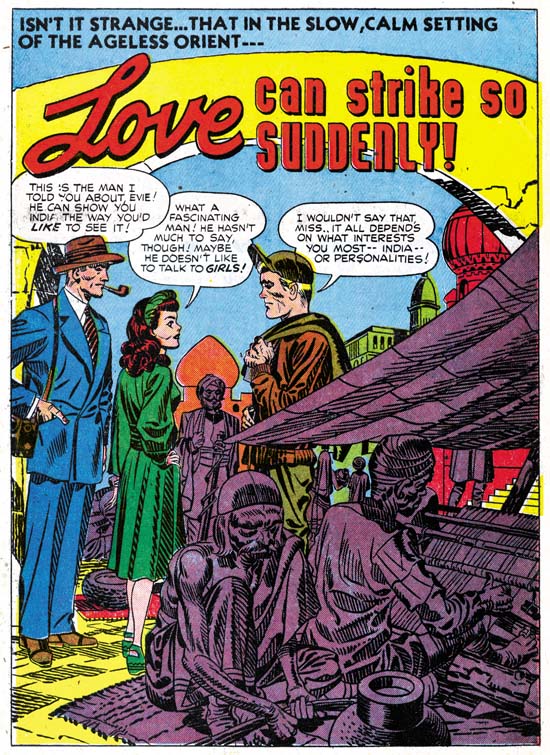

Young Romance #8 (November 1948) “Love Can Strike So Suddenly”, art by Jack Kirby

Kirby may have tuned down his use of action but he still looked for means to keep his stories exciting. One of his techniques was to make use of the exotic location of some of the stories. Had the splash of “Love Can Strike So Suddenly” depicted a normal local it would have seemed quite banal. All the main characters are just standing around. Even the dialog is not nearly dramatic enough to rescue this page. However by inserting his cast into a street in India, Jack has made this one of his memorable splashes. I am sure Kirby has swiped this from some source, perhaps National Geographic, but I am also certain that he has made his version far more interesting then the original. I have recently discussed this story; it is the source for a swipe used years later in Simon and Kirby’s own romance comic In Love.

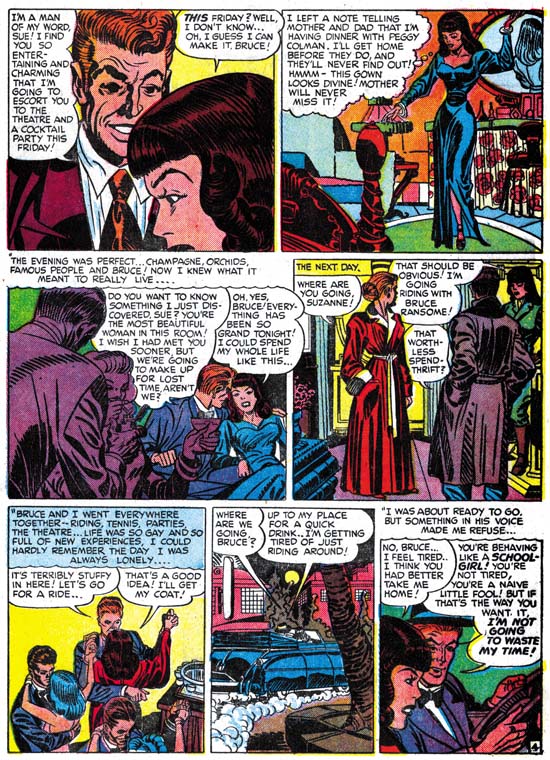

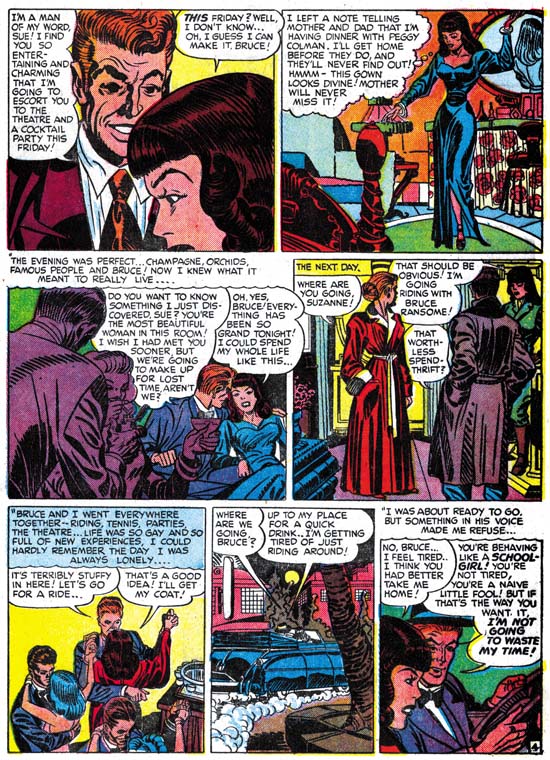

Young Romance #7 (September 1948) “Mother Said No” page 4, art by Jack Kirby and Carmine Infantino?

The Jack Kirby Checklist does not include “Mother Said No” among its listings of Kirby’s work. It is easy to understand why, the man in the first panel of the page imaged above does not look he was drawn by Jack. Or does he? Kirby often drew his men with wild eyebrows but these look excessive even for Jack. But how much of these exaggerated eyebrows were in the original drawing and how much were due to the inker’s interpretation of the pencils? The layouts throughout the story look like they were done by Jack. It is hard to be sure, but once the eyebrows are ignored a lot to the drawing looks like Kirby to me.

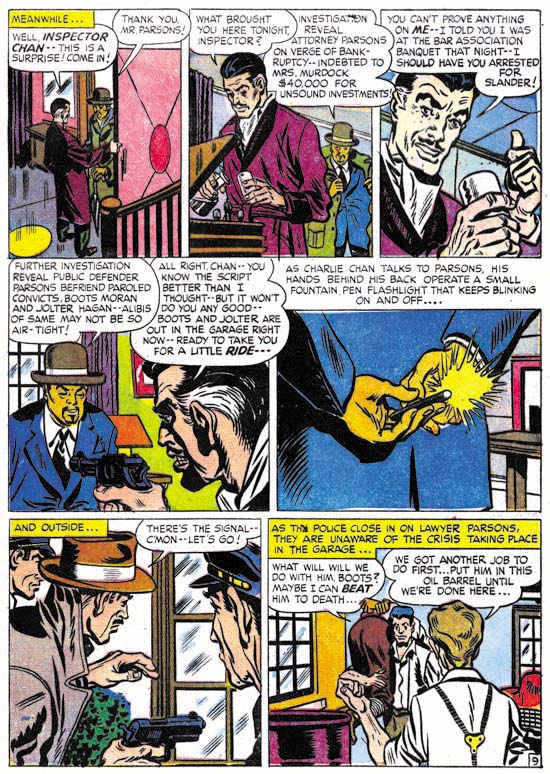

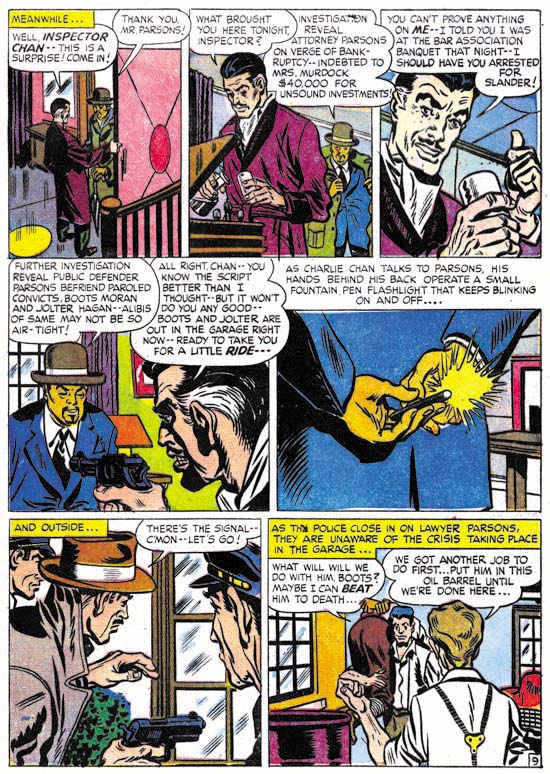

Charlie Chan #1 (June 1948) “The Hit and Run Murder Case” page 9, art by Carmine Infantino

Nearly identical men’s eyebrows seen in “Mother Said No” can also be found in work that Carmine Infantino did in Charlie Chan. Compare the man in the third panel of page nine of “The Hit and Run Murder Case” shown above to the one in the first panel of the page I previously presented from “Mother Said No”. Further examples of Infantino’s work for the Simon and Kirby studio can be found in an earlier post. While the details of the eyebrows seem to match in the two stories, the proportions used in drawing the faces do not. Nor are Carmine’s layouts in Charlie Chan similar to those found in “Mother Said No”. The inking for “Mother Said No” was done in the studio style which would normally suggest Jack or Joe’s involvement. However Carmine used the studio style inking in some parts of Charlie Chan, particularly the splashes. I really need to do a more thorough comparison, but some of the spotting in “Mother Said No” does not look like it was done by either Jack or Joe. My initial conclusion is that in “Mother Said No” Carmine was inking Jack’s pencils. If that is true what is not clear is whether Kirby’s pencils were not very tight, or if instead they were overwhelmed by Carmine’s inking. In either case I am presently inclined to consider this a joint piece with Jack as the primary artist.

There is a serious problem with the analysis that I presented above because of an interview of Carmine Infantino from The Jack Kirby Collector #34. In that interview Carmine clearly said that Charlie Chan was the only work he did for Simon and Kirby, and later added that he never inked Jack’s pencils. I really want to do a more careful analysis before I am ready to contest Infantino’s statements so for now I consider my conclusions as preliminary. Hopefully a re-examination of this issue will be the subject of another post in not too distant future.

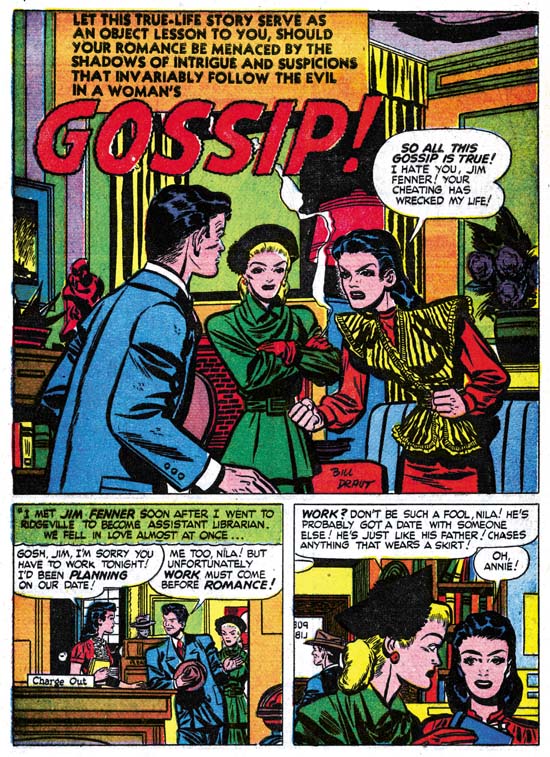

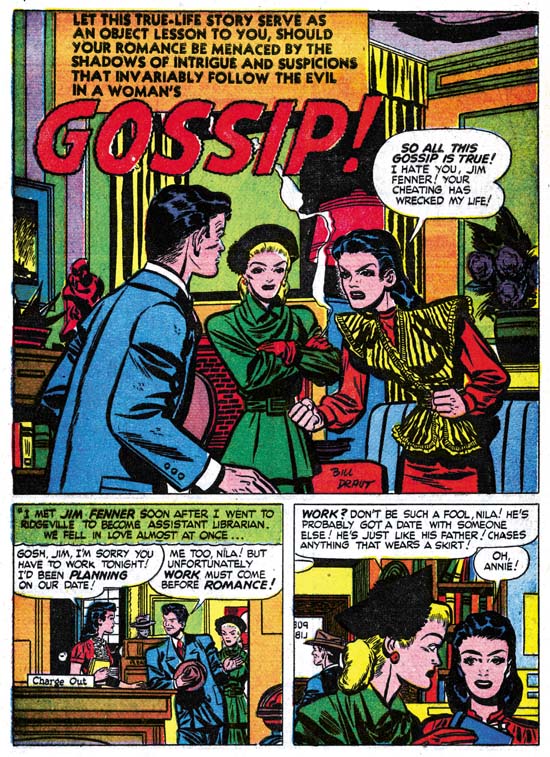

Young Romance #6 (July 1948) “Gossip”, art by Bill Draut

Kirby did not draw all the stories in YR #5 to #8; Bill Draut remained a significant contributor with seven stories out of twenty, or 52 pages out of 177. Bill’s art started to change. Gone were the splashes with an emphasis on design, I do not believe it would reappear in Draut’s work until 1954 for In Love. I suspect Joe Simon had a hand in laying out some of the earlier Draut splashes for Young Romance, but from this point on Draut would do it himself. The other change would be the appearance of more and more traits that would be typical of Draut. Note the brickwork for the fireplace in the “Gossip” splash. This is a Draut trademark that will reappear from time to time through his association with the Simon and Kirby studio. Another Draut trademark, which actually showed up before, is the brunette’s pose. Draut portrays a person’s anger by leaning the torso and thrusting the head forward, and sometimes having the person clench their fists. This is a pose not quite like any that I have seen Kirby use and it is one of the reasons that I do not believe Jack was providing layouts for Bill as some authorities have claimed.

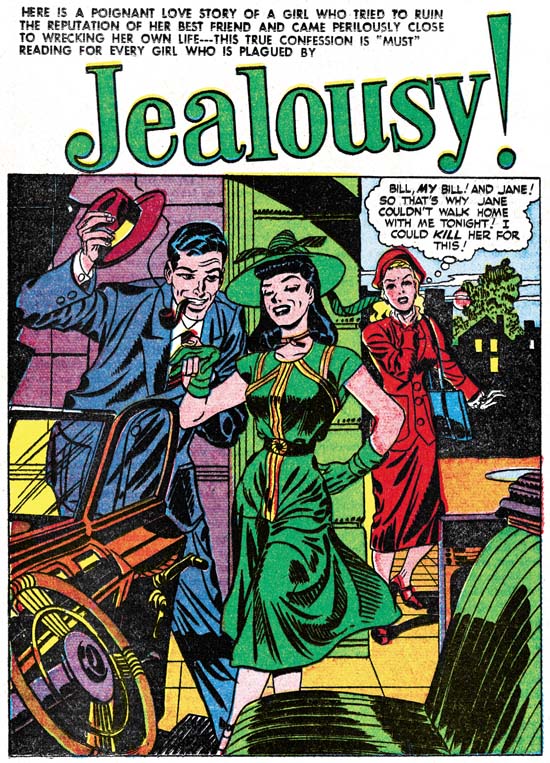

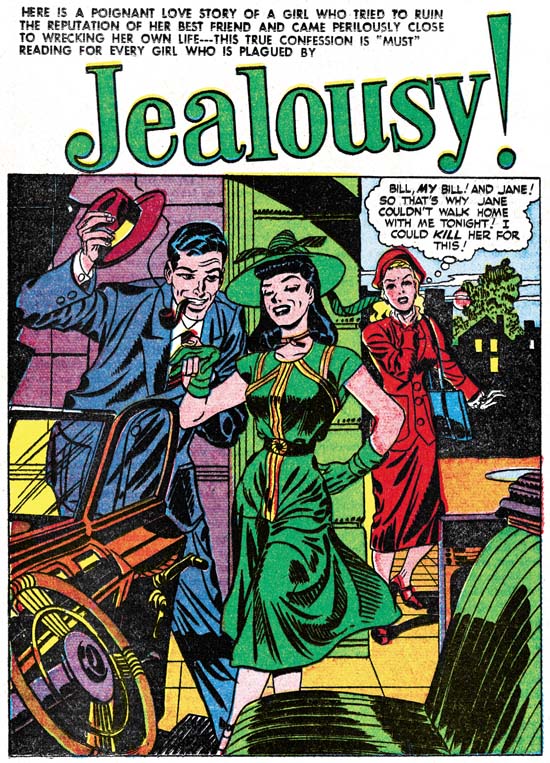

Young Romance #5 (May 1948) “Jealousy”, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

The final two contributors to Young Romance #5 to #8 was the team of Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin. I attribute three stories from issues #5 and #6 to Robinson and Meskin, one of which (“The Inferior Male”) was signed. The Jack Kirby Checklist credits the splash page of “Jealousy” to Jack Kirby as inked by Joe Simon. The expressive formality of the foreground couple is not typical of Kirby. Nor are the long and simple eyebrows usually found in Simon’s inking. The only thing that suggests Kirby/Simon to me is some of the Studio style inking such as the abstract arch at the top of the wall and the picket fence crosshatching on the lower part of the woman’s dress (see inking glossary). However the “Jealousy” splash presents cloth folds created by long, narrow sweeping brush strokes, this is exactly the inking technique used by Mort Meskin. Also note the man has a type of grin that is so typical for Mort. The eyebrows found in “Jealousy” may also be found in the Robinson and Meskin work found in these early issues of Young Romance. The unusual formal pose of the couple would not be surprising for Robinson and Meskin. The only problem with a Robinson and Meskin attribution for the “Jealousy” splash is the Studio style inking which is not found in other R&M art. I think the best explanation for this discrepancy is that either Simon or Kirby in their roll as art editor stepped in to touch up the splash. I feel the splash matches the art in the rest of the story and it all should be attributed to Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin.

July marked the last month that Robinson and Meskin art would appear in Simon and Kirby productions. Mort Meskin would return by himself over a year later, after which he would be a frequent contributor until the end of the studio. This is all very hard to reconcile with Carmine Infantino’s TJKC #34 interview where he says that he accepted the Charlie Chan job for the experience he would get by working with Kirby and Meskin. Carmine even describes Mort as working right next to Jack. Carmine’s stay was from June 1948 until February 1949 (cover dates). This does overlap Robinson and Meskin’s period (January to July 1948) but is well before Meskin’s solo return in December of 1949. I just do not find it creditable that Mort was working in the studio at a time when he and Robinson were probably producing more work for other publishers then for S&K. Would Mort and Jerry have been working separately? Would the small amount of work for S&K justify Mort’s presence in the studio? I am afraid I have to conclude that Carmine’s memory has failed him; perhaps he has mixed up the time of his presence in the studio with that of his brother Jimmy who did work for S&K at the same time as Meskin.

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)