(Young Romance #1 – #4)

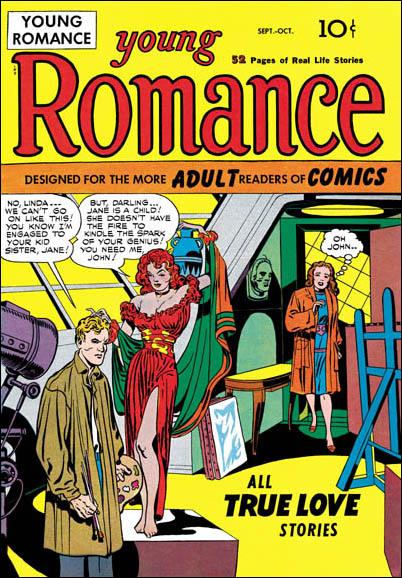

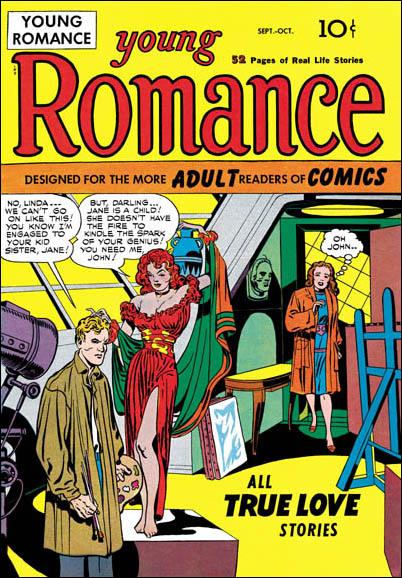

Young Romance #1 (September), art by Jack Kirby

Simon and Kirby had a pretty consistent modus operandi for developing a new title. Basically it called for Jack Kirby providing much, if not most, of the initial art. This M.O. was adhered to with Young Romance, for the first four issues Jack drew 10 of the 20 stories. Page production rates (the number of pages of art created in a month) at the time of the release were also very high. Joe Simon has stated that before they went around to various publishers, they had already created the art for the initial issues. That way if some unscrupulous publisher liked the idea but wanted to develop it themselves, Simon and Kirby would have a head start. Therefore the high page production rates are misleading because much of the art was actually done earlier. Even so the initial art for Young Romance was rushed. Not that Jack would sacrifice drawing quality, but the inking would initially be rather simple. S&K shop inking traits such as picket fence crosshatching (see the Inking Glossary) would find limited use. The resulting inks would be reminiscent of the Austere inking style from the late fifties which developed from a similar need for increased art production. Although the inking was simpler what was done was quite beautiful, so once again quality was not sacrificed.

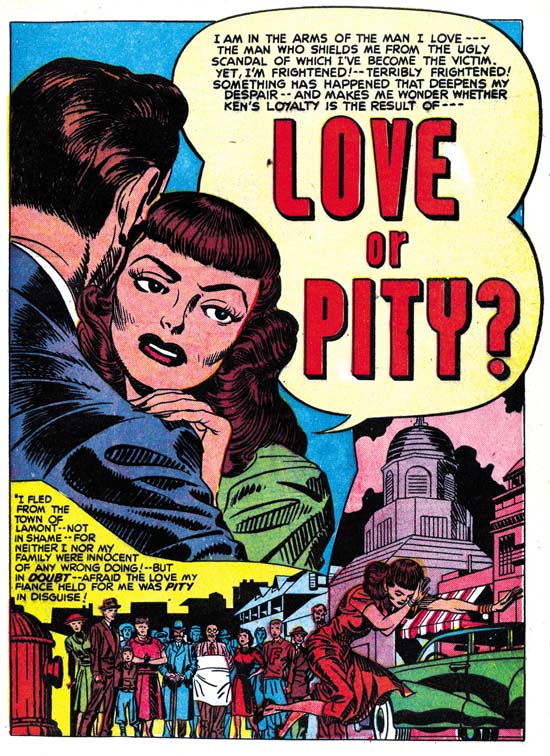

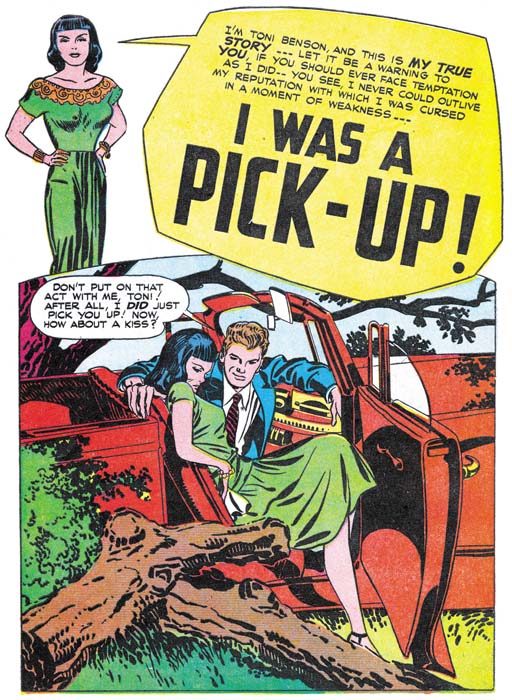

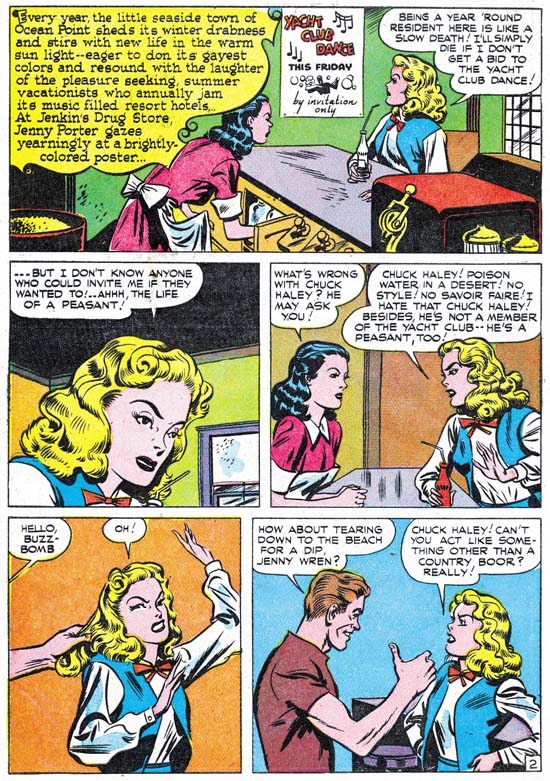

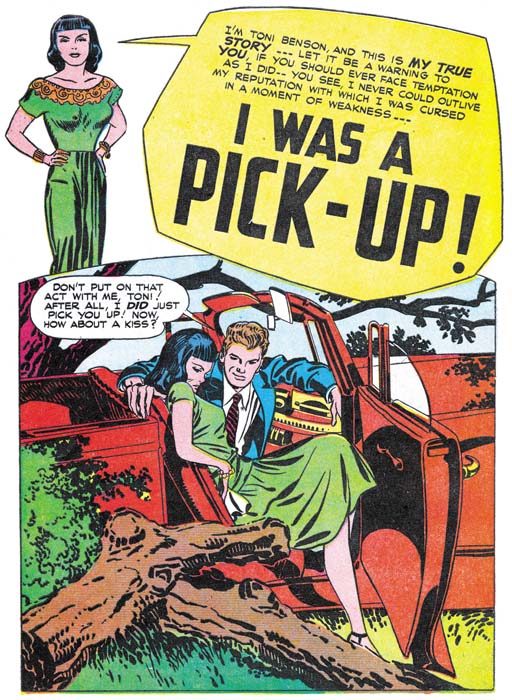

Young Romance #1 (September 1947) “I Was A Pick-Up”, art by Jack Kirby.

The drawing for the romance covers are generally not Jack Kirby’s finest work. Kirby’s forte was action, which was not the sort of thing appropriate for romance. Jack would compensate by using various compositional devices to keep the image visually interesting but this was not completely successful. Much of the impact these covers have is based not so much on the drawing itself as the melodrama that is being depicted. The less then graphically successful covers cannot be blamed entirely on romance genre not being conducive to Jack’s talents. Some of Kirby’s best efforts from the period can be found in romance splashes. The one for “I Was a Pick-Up”, shown above, is a great example. This splash is much more graphically interesting then the cover for the same issue. The compositions centers on the semi-reclining figure of woman. Her posture is deliberately provocative while at the same time projects her discomfort at her current predicament. Her pose is echoed in the foreground of bush and tree trunks with one of the fallen tree’s limbs repeating the lady’s bent legs. Part of the lady’s visual confinement is formed by the tree trunks, the rest is the by the arms of her not so gentleman companion and the door of the car. This composition seems so expressive and natural that is easy to overlook some logical inconsistencies. Why is the car door open? If it is for her eminent escape, why does the lady seem to lounge about as if reluctant to leave? I would say the whole point of this splash is to highlight the illogic of her situation. Part of her is fully aware that she should get out of the car but this is battled by the same temptation that lured her into becoming a “pick-up”. Although nothing explicit by today’s standards, this was steamy stuff indeed. Too proactive for a cover where it might attract the unwanted attentions of those critical of the idea of a romance comic book, but just right to attract the potential purchaser who was interested enough to open the book. Not every Kirby romance splash would be this good, but enough of them are to indicate that Kirby could do great pieces of stand alone romance art. His best romance work would just be a little too much for the cover.

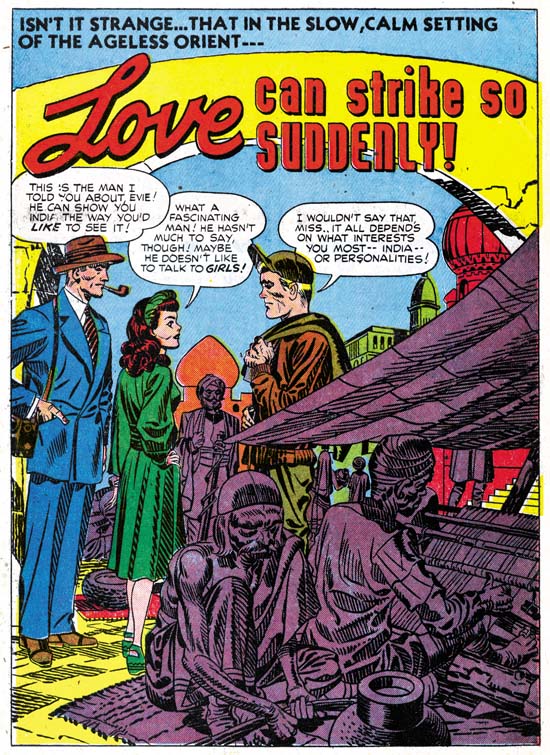

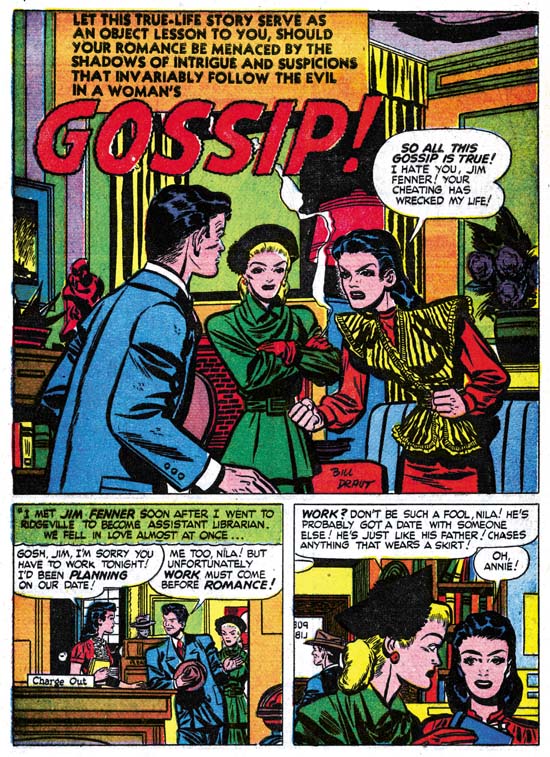

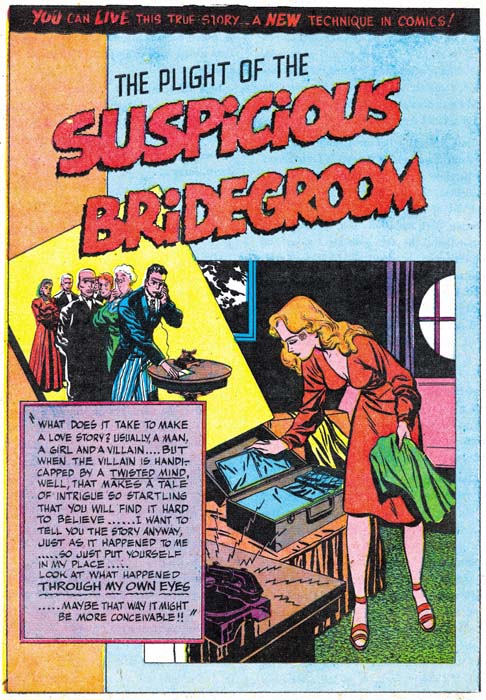

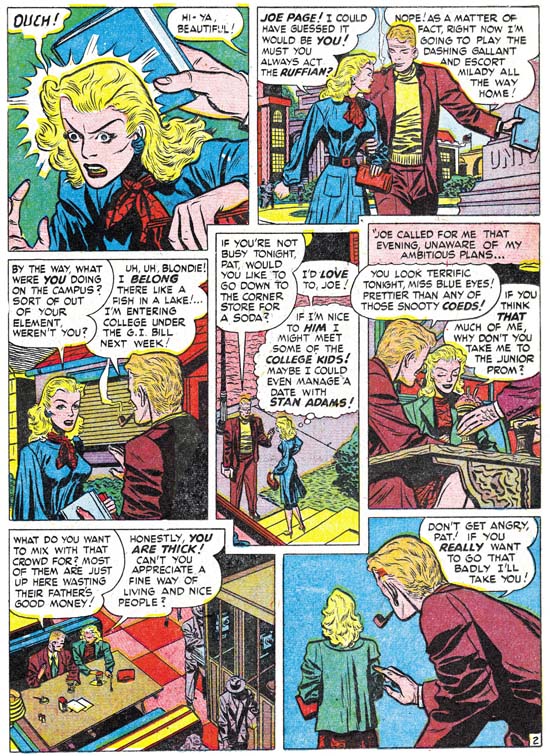

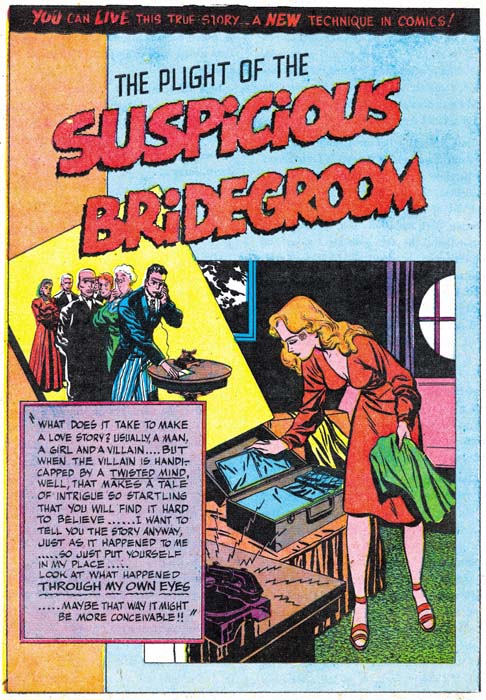

Young Romance #1 (September 1947) “Suspicious Bridegroom”, art by Bill Draut.

Kirby did not pencil all the art for the initial issues of Young Romance. Of the first 20 stories, Kirby did 10 while Bill Draut provided 7. Draut had met Joe Simon in Washington during the war and had accepted Joe’s invitation to join them in New York. Bill was a talented artist but had no previous comic book experience. Even so Draut did some nice work for Simon and Kirby in titles they developed for Harvey in 1946 (Boys Explorers and Stuntman). Although some work by Bill Draut was published after that, it was all stuff left over from that quickly scrapped S&K Harvey line. One wonders what Bill did between that attempt and his appearance in Young Romance over a year later. From YR #1 on until the closing of the studio, Bill Draut would be a consistent presence in Simon and Kirby productions.

Draut was relative new to comic book work, but that did not stop him from trying to be innovating. A good example is the splash page for “Suspicious Bridegroom” shown above. The layering of the caption box and two images over a bicolor background is very effective. Particularly with the way the panel for one of the images is skewed and casts a shadow. The woman is very attractive but seems directed more to appeal to a man then a teenage girl reader. It was not unusual for Bill to present “cheesy” images of woman in his earlier efforts in the romance genre.

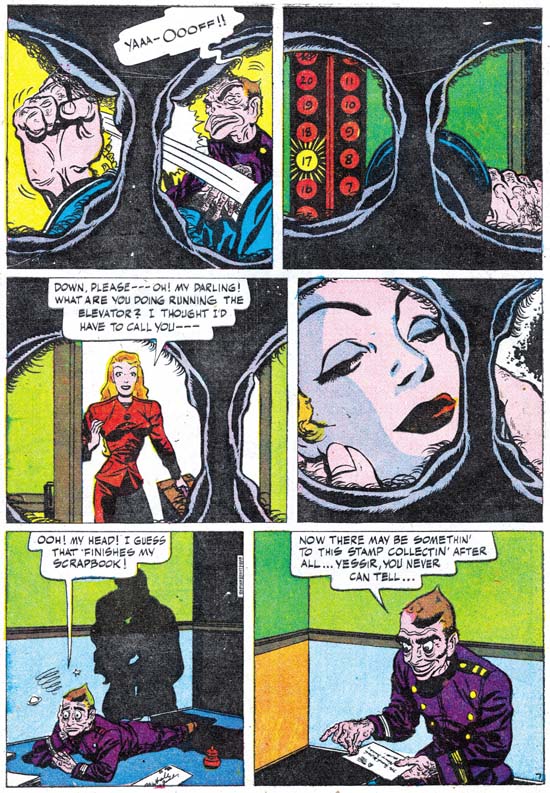

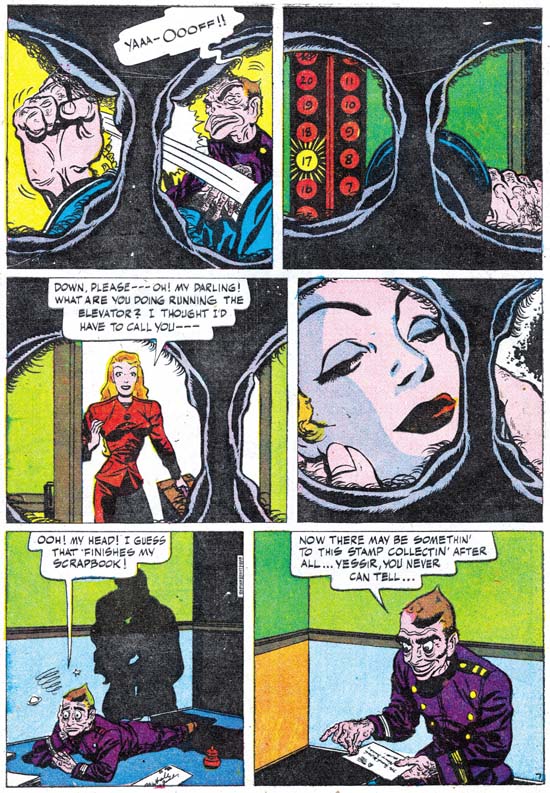

Young Romance #1 (September 1947) “Suspicious Bridegroom” page 7, art by Bill Draut.

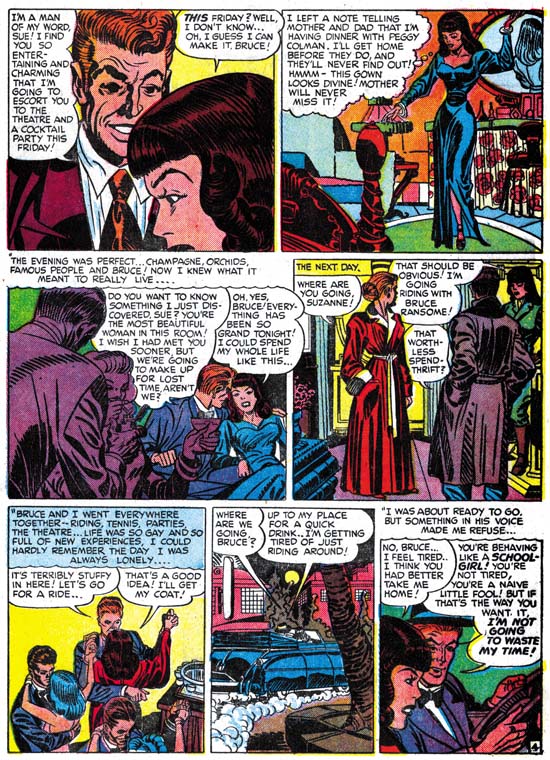

Not all of Draut’s attempts at being innovation were successful. On the top of the splash page for “Suspicious Bridegroom” we find the declaration:

YOU CAN LIVE THIS TRUE STORY… A NEW TECHNIQUE IN COMICS!

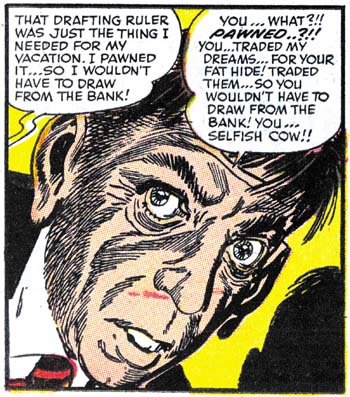

The announced technique, showing up in much of the story, consists of providing the images as if view through someone’s eyes. Well that is what it was meant to be but actually it looks like a view from some sort of bizarre binoculars, what with the circular views surrounded by irregular folds (eyelids?) and numerous eyelashes. Frankly the technique is not very effective since it puts a severe limit on what can be shown in a panel. Worse yet it is actually kind of creepy and that casts a chilling effect on was meant to be a romantic scene in the fourth panel. Fortunately this innovation was not to be repeated in future work by Bill Draut or any other artist working for Simon and Kirby. Even though it was a failure, you still have to admire the daring of the attempt.

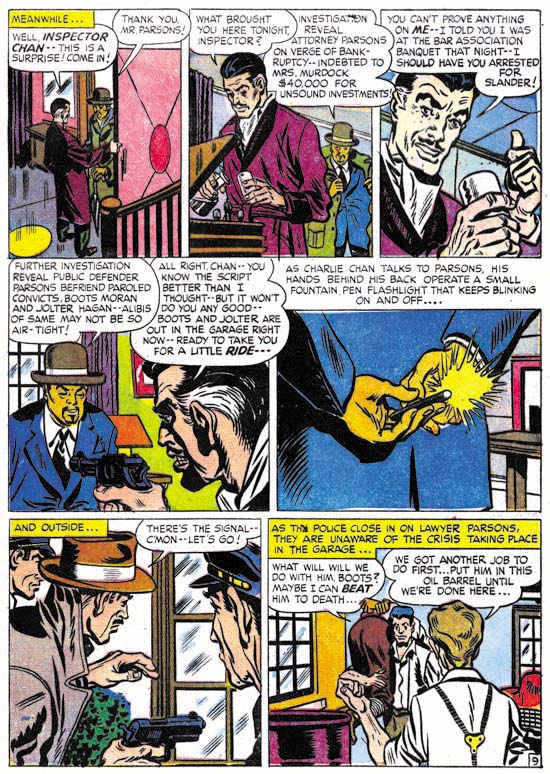

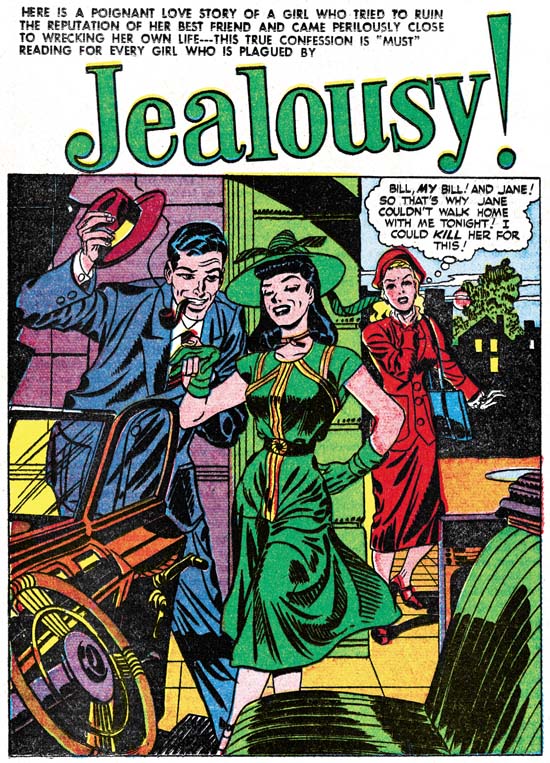

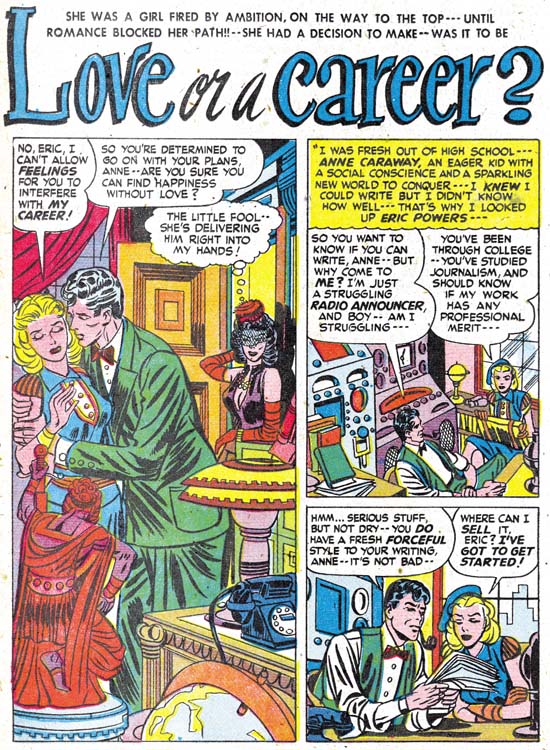

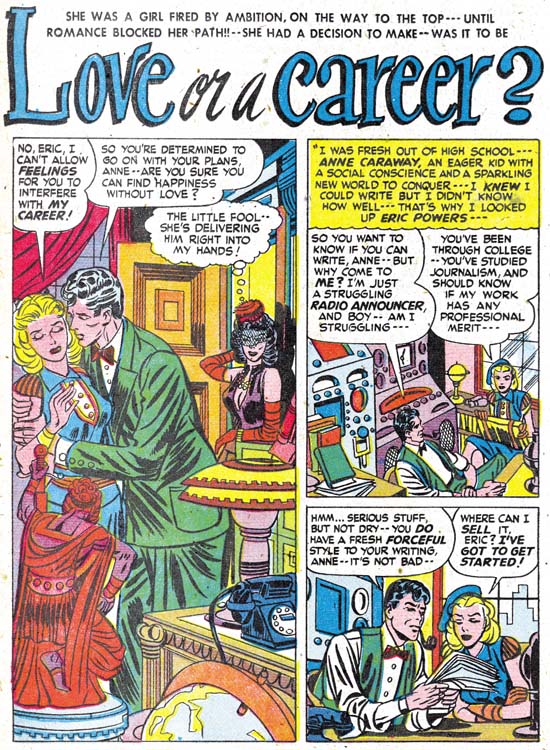

Young Romance #3 (January 1948) “Love or a Career?”, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin.

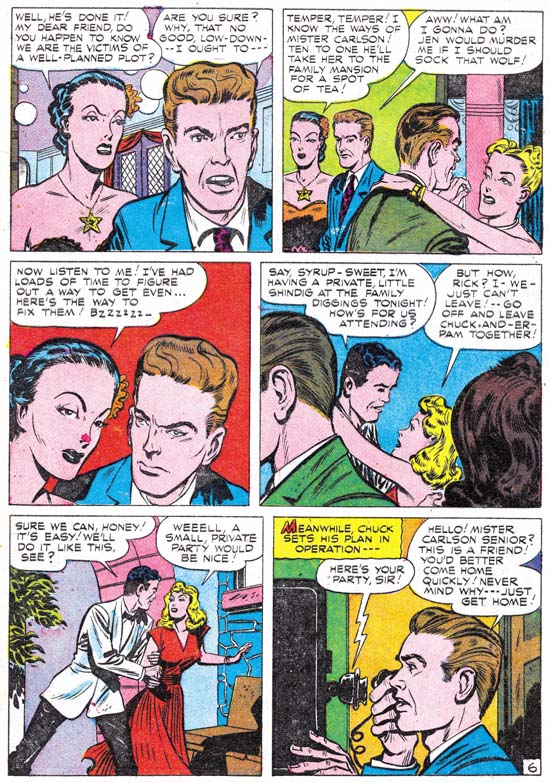

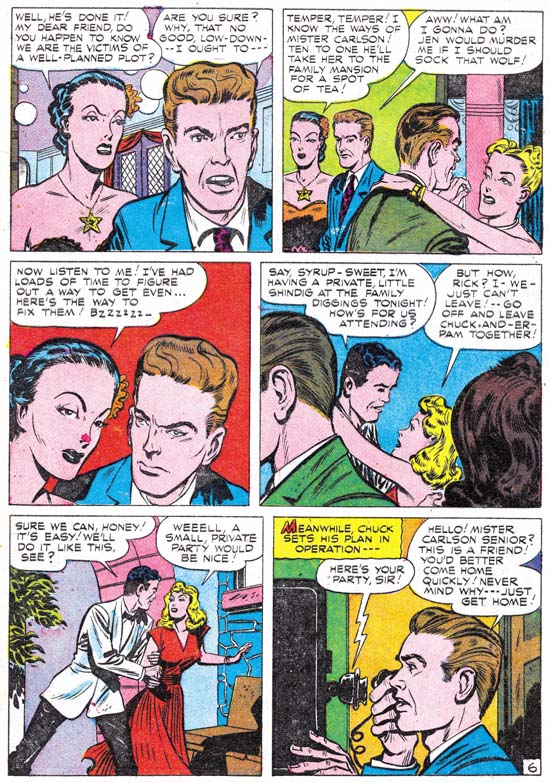

In YR #3 (“Love or a Career?”) and YR #4 (“I Love You, Frank Gerard”) are stories by another artists, or more correctly a pair of artists, Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin. These two works are unsigned but in the same style as signed work done a few months later (see my post on the cover for My Date #4). I have not seen enough of either artist’s earlier work to be confident about how the two artists collaborated, but my suspicion is that most of the pencils were done by Robinson and Meskin did most of the inking. I am not sure how Simon and Kirby met Jerry Robinson, but Meskin was well known from the time that S&K worked for DC. There is a story of both Kirby and Meskin facing deadlines and ending up in the DC bullpen on adjacent drawing tables. Each was intent on getting their own jobs done while other artists gathered to watch two of the industries greatest and most prolific artists racing away. I have not come across any comments from Jack Kirby about Meskin, but Joe has repeatedly expressed his admiration for Mort’s work.

Now that I have introduced most of the artists from the first four issues of Young Romance, this seems to appropriate time to address a subject that I have avoided in the past, that is the question of Kirby layouts. This is a claim that many people have declared about work done by the various artists who worked for the Simon and Kirby studio. Unfortunately the use of Kirby layouts is not the only possible explanation for other artists doing Kirby-like work. Many admired Jack’s artistry so it is not surprising that they would imitate or even swipe from Kirby. From time to time Jack would also assume the job of art editor and fix up the work from other artists prior to publication (for example). One of the criteria I use to distinguish Kirby layouts from things like swipes and art editing is consistency throughout the story. Swiping and art editing will be limited to a few panels here or there, not to the entire story. But if Kirby is truly providing a layout it would be expected that he would do so for the entire story. As for distinguishing a Kirby layout from a Kirby imitator it is necessary to compare the work in question to the layouts found in contemporary Kirby stories. It is expected that Kirby would provide layouts similar to those of his own stories. While it is possible that Kirby might provide simpler layouts, it is not creditable that he would introduce techniques into a layout that he would not use himself.

Kirby uses an unusual layout for some of his splashes. It consists of a half splash along with a figure or just the head with a speech balloon that serves the place of title caption. The splash from “I Was a Pick-Up” shown earlier is an example of this layout. This layout is not used by any other artist in the first four issues. However it is not the only splash layout used by Kirby either. Careful examination shows that it is only used on for the first story in the comic. So although it is very distinctive layout, the fact that the other artists do not use it does not prove their stories were not done using Kirby layouts. Although I call this a Kirby layout I might be more accurate to ascribing it to Simon and Kirby. Both Joe and Jack have said that Joe did layouts for some covers and splashes. Did Joe consistently provide layouts? Was Joe providing layouts for Jack only early in their collaboration? At this point I do not have really firm answers for these questions. It does seem to me that many of the splashes and covers have emphasis on design found in work that Joe did prior to working with Jack and would continue to use after they broke up. However this fondness for certain types of designs disappears from Jacks work once he split from Joe. Therefore I am inclined to feel Joe provided some layout guidance to many of Jack’s covers and splashes. However nothing in the layout of Jack stories seem unique to his period of partnership with Joe, so I believe that the story layouts at this stage are Kirby’s alone.

As I previously mentioned, Bill Draut did some interesting designs for some of his splash pages in these early Young Romance issues. He used tilted panels in two of his splashes, a device that does not appear in any Kirby drawn splash from the same comics. Draut also would occasionally introduce a “sexy” or “cheesy” pose; this is something Jack was not seen to do. Bill Draut would develop his own way of telling a story which is only beginning to appear in these early romance works. Still the story layouts that he uses for these first issues of Young Romance only occasionally, if at all, remind one of Kirby. So I would conclude that there are no Kirby layouts under the Bill Draut pencils in the first four issues of Young Romance. Actually this is a conclusion that I have reached for all of Bill Draut’s work for S&K.

The opening splash panel is generally used to as a sort of comic book equivalent of a movie trailer. That is it provides a sort of condensation of what the story will be about. However the splash panel normally is not actually part of the story itself. Sometimes the entire first page is given over to the splash. Five splashes by Kirby and two by Draut from the first twenty stories are full page splashes. I am not sure that much can be deduced from the use of full page splashes, except perhaps that Kirby was more prone to use them then the other artists. Often the first page would be a combination of a splash panel and one or two story panels, and how they are laid out is informative. Kirby’s next most frequent first page arrangement, with three cases, places a single story panel in the lower right corner. That layout is not used by any of the other Young Romance artists. The other arrangement that Jack used was to restrict the splash panel to the top of the page, and provide two story panels below. This is the most common arrangement in the first four issues; Kirby did it twice, Draut five times and another artist also used it once, for a total of eight out of twenty stories. Another possible layout is for the splash panel to occupy the left while the two story panels are placed on the right. That arrangement was not used by either Kirby or Draut in the first YR comics but is used for both stories provided by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin. To me this strongly suggests that Jack did not provide layouts to Robinson and Meskin.

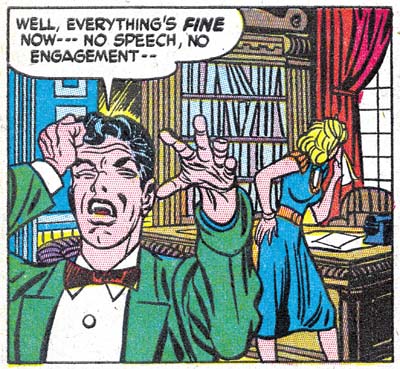

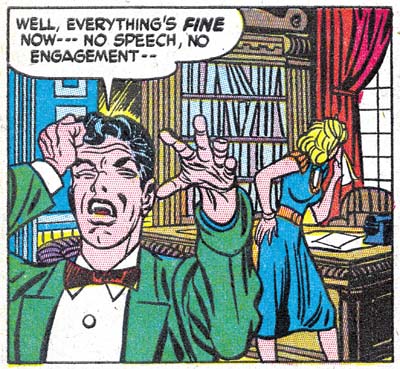

Young Romance #3 (January 1948) “Love or a Career?” page 7 panel 1, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

As was the case with Bill Draut, the way that Robinson and Meskin present the story is not consistently like what Kirby did. One exception that might be made is provided in the above panel. Jack Kirby was justly famous for his use of exaggerated perspective. The way the man holds his hand out toward the view does remind one of Jack’s techniques. In my opinion Robinson and Meskin are not as successful in their effort as Kirby would have been, so I do not think this would be an example of Kirby stepping in as an art editor. Although Kirby did have a fondness for this sort of difficult perspective, he did not use it, or anything like it, in any of the stories that he drew for YR #1 through #4. If Jack did not use it for his own drawings, I do not think it would be likely that he would use it in layouts for other artists at that same time. Therefore I conclude that this panel is an example of Robinson and Meskin being influenced by Kirby and it is not based on Kirby layouts.

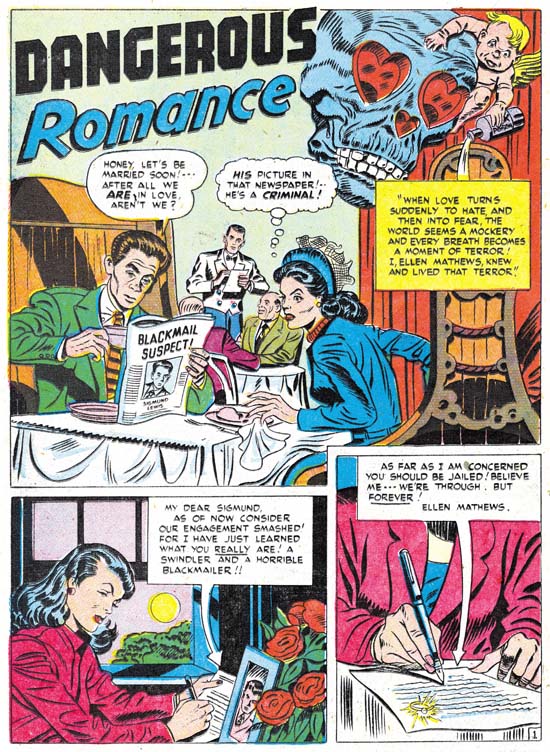

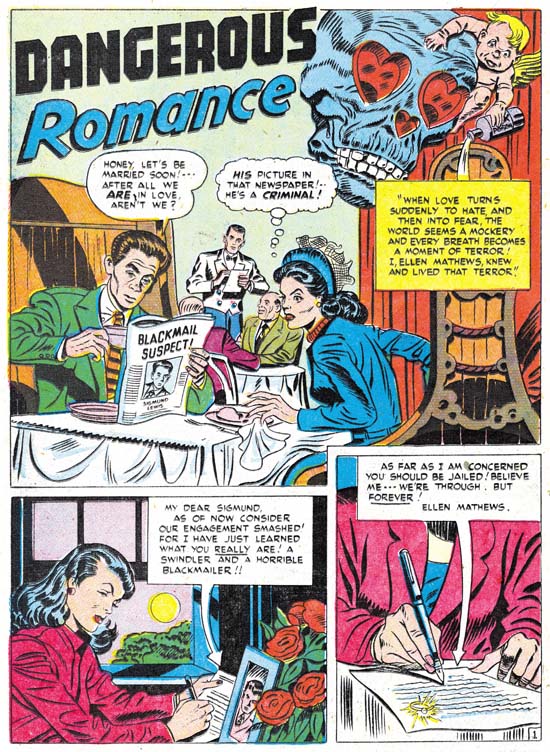

Young Romance #2 (November 1947) “Dangerous Romance”, by unidentified artist

Normally I do not associate the use of floating heads with Kirby’s covers or splashes. They were not used extensively by Kirby during the S&K period and became extremely rare after he left Joe. Simon on the other had used them on some of his covers done early in his career as well as after the split-up. Whether it is another suggestion that Joe may have been involved in laying out some of the splashes, or that Jack may have just adopted if for a period, but the use of floating heads becomes frequent in the initial Young Romance comics. Five out of ten Kirby splashes use floating heads; on the other hand this device is not used in any of the stories by Draut or Robinson and Meskin. This is another suggestion that Jack did not provide those artists with layouts. But the design technique does show up in the story “Dangerous Romance” in Young Romance #2. The story layout is similar to that Kirby would use for his own work, and this similarity is found throughout the story. The inking also seems to mimic S&K studio style. Note the abstract arc shadow in the splash, and something akin to should blots are sometimes used in the story (see the Inking Glossary for explanation of these terms). Even the penciling is reminiscent of Jack’s work. I do not believe this is an example of a heavy handed inker working over Kirby pencils. As far as I know no one has ever attributed the drawing of this story to Jack. So the conclusion I reach is that this is an example of an artist working from Kirby layouts and trying, not very successfully, to mimic Kirby as close as he was able. Unfortunately I have no idea who the artist was.

Young Romance #1 (September 1947) “Summer Song” page 6, art by Jack Kirby and an unidentified artist.

There was a time in the past that I did not believe “Summer Song” was penciled by Jack Kirby. I found that pages such as the one imaged above deviated in ways that could not be explained by some heavy handed inker. Christopher Harder (a fine S&K scholar) pointed out to me that the art seem to progress from very much like Kirby’s work in the beginning followed by work that looked less and less like Jack’s. You can see what he means be comparing the above image with another from early in the story that I provided last week in the first chapter of this serial post. I remained perplexed about the attribution of this story until one day Joe Simon showed me an article from a Marvel publication. I deeply regret not borrowing it, because I have not yet come across it again in Joe’s collection. It was an interview with an artist, I am sure it was either Joe Sinnott or John Romita. What I do remember clearly was one part where the artist describes approaching Simon and Kirby about a position they had open. The artist described the work as an in-betweener. He went on to say that Jack would draw the story pretty tightly to begin with and then get much looser and close it with some more tight pencils. The hired artist would then tighten up all in between pages and ink the whole thing. This would allow Jack to work more quickly and yet maintain some control over the final results. (Incidentally the artist interviewed said that S&K provided him with samples to work on to show how well he could do the work, but that he never followed through with it). When I read that interview I realized he was describing exactly what had been done in “Summer Song”. In fact when I reexamined the final page of the story it did look more Kirby-like then those done in the middle. It would not be accurate to call such an arrangement as Kirby layouts, Jack contribution was too much for that. Nor would it be correct to describe the other artists as just the inker, for he did much more then just ink Jack’s pencils. So I have decided to attribute the work to both artists. Unfortunately once again I have no idea who the second artist was. In The Complete Jack Kirby, Greg Theakston attributes the inking of this story to Charles Nicolas but gives no explanation how he came that that conclusion.

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)