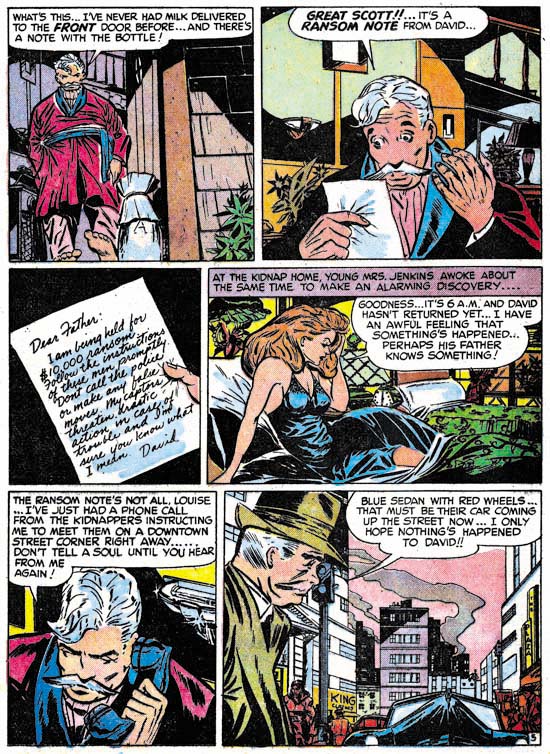

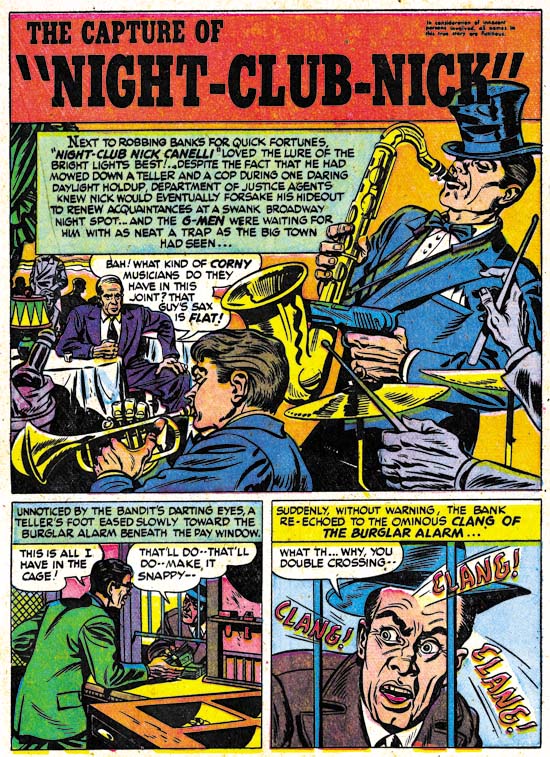

There was no true connection between the team of Simon and Kirby and Captain Aero Comics. Captain Aero was just one of a number of wartime publications (lasting from December 1941 until August 1946). Holyoke is usually said to be the publisher for this comic but the indicia from later issues list Continental Magazines. This may be nothing more then the use of an alternative name, a common practice at the time, but irregularities in the issue numbering (there are no issues #18, 19 or 20) suggests that the title may have truly had a change in publishers. The connection referred to in the title concerns some of the artists whose work appeared both in Captain Aero as well as in various Simon and Kirby productions. There is nothing particularly surprising about this as both were small outfits getting work from an assortment of comic book artists. I am sure that careful examinations of other smaller publications would reveal artists that had also worked for Simon and Kirby. Because Captain Aero comes from an earlier period it nicely shows how extensive these artists’ style had evolved. Had these works been unsigned, I doubt that I would have identified any of the artists.

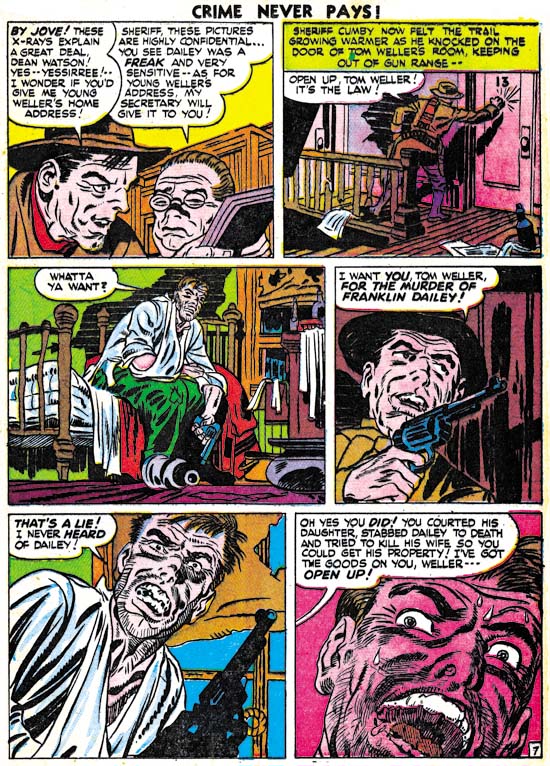

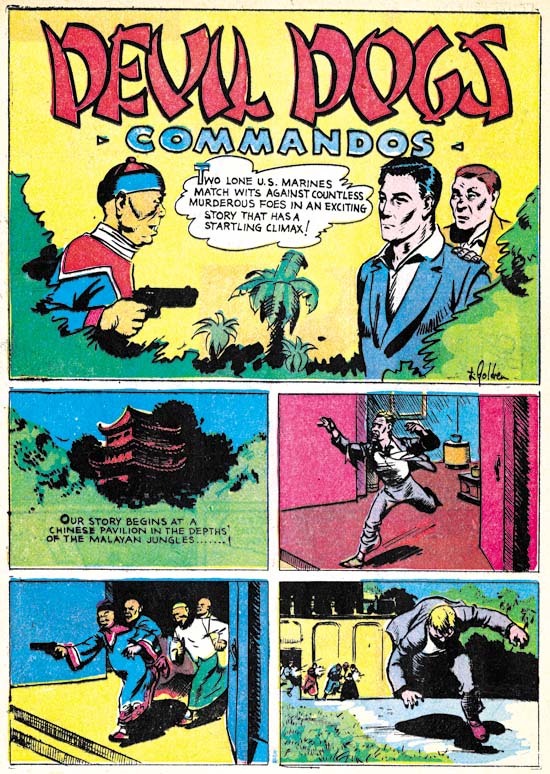

Captain Aero #7 (July 1942) “Devil Dogs Commandos”, art by Louis Golden?

The first artist from Captain Aero with a Simon and Kirby connection has been somewhat of an enigma. His two known S&K works were signed on the last page but the signature has been difficult to decipher. The handwriting of the signature found on the splash panel of “Devil Dogs Commandos” is the same but a little clearer. The initial is either an ‘L’ or a ‘T’ or an amalgamation of both. The first letter of the last name looks like a ‘G’ so my current reading of the name is L. or T. Golden. There is an artist named Louis Golden listed at Atlas Tales as having contributed to Mystic #10. The Who’s Who of American Comics cites Golden as having worked for Holyoke in 1942-43 on Blue Beetle, Enchanted Woods and Monkey Fencer. Captain Aero #7 has not been indexed yet in the GCD but one of the few works that the CGD lists for Louis Golden is from Veri Best Sure Fire Comics #1 listed as a reprint form an unspecified Captain Aero issue. The title in Sure Fire #1 (“Commandos of the Devil Dogs”) is just a slight rewording from the title found in Captain Aero #7 as to leave little doubt that they are the same story. While I have not seen any of the work these various Internet sites attribute to Louis Golden this information is favorable enough that I am now tentatively identifying him as the artist in question. Golden did not do much work for Simon and Kirby but it is still nice to be able to provide a name for that work.

Fortunately the signature is very distinctive because the artist’s style here is so different from his work for Simon and Kirby (Justice Traps the Guilty #7 and Charlie Chan #1). There is no sign of the massive, square faces that is such a distinctive feature in his later work. While I admire the art he did for S&K, I find this Captain Aero piece to be rather crude.

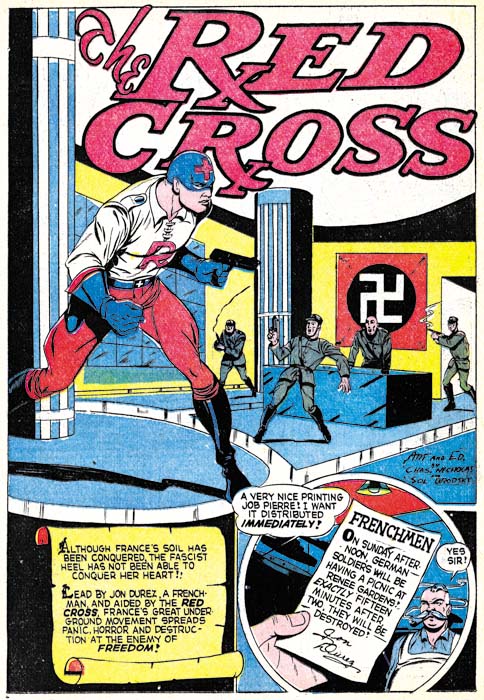

Captain Aero #9 (November 1942) “The Red Cross”, art by Charles Nicholas & Sol Brodsky

Charles Nicholas has been credited with being the creator of the Blue Beetle, but which Charles Nicholas is this one found in Captain Aero? Is this the artist otherwise known as Charles Wotjkowski who worked for Simon and Kirby after the war? I am not positive but the style suggests it is. Actually the work for Captain Aero (two stories and one cover all of the Red Cross feature) seems more professional then his S&K crime story (Headline #31). Perhaps that is due to the inking by Sol Brodsky, a talented artist in his own right who did the pencils for another piece in Captain Aero.

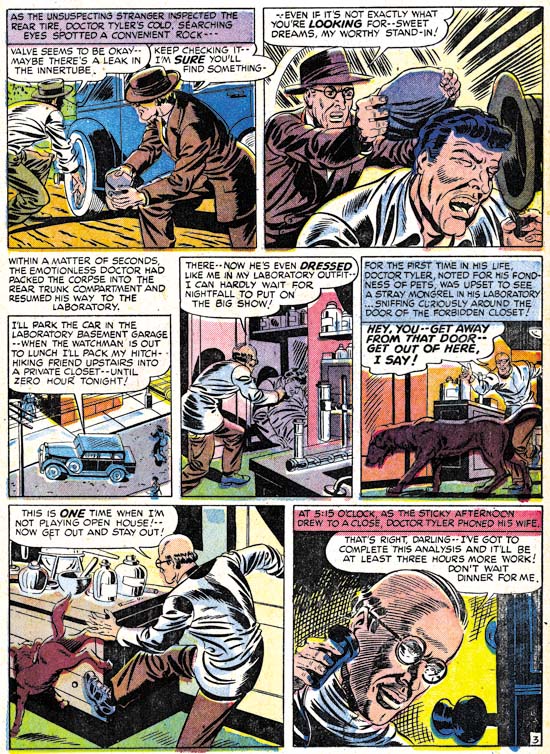

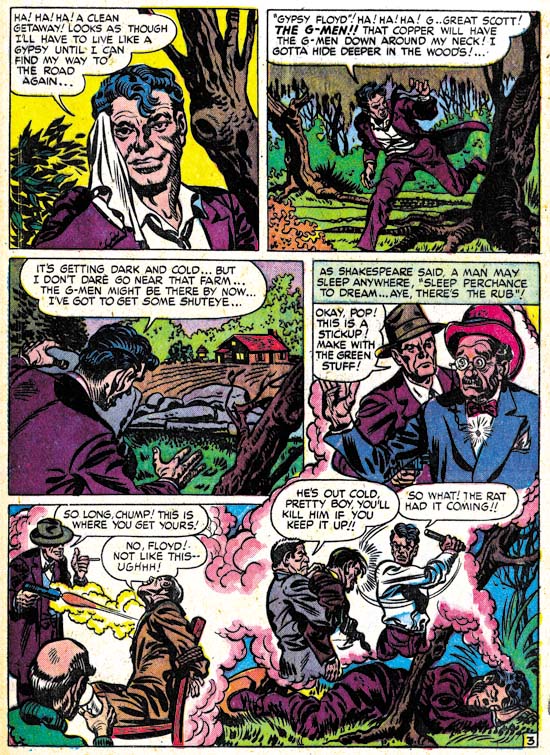

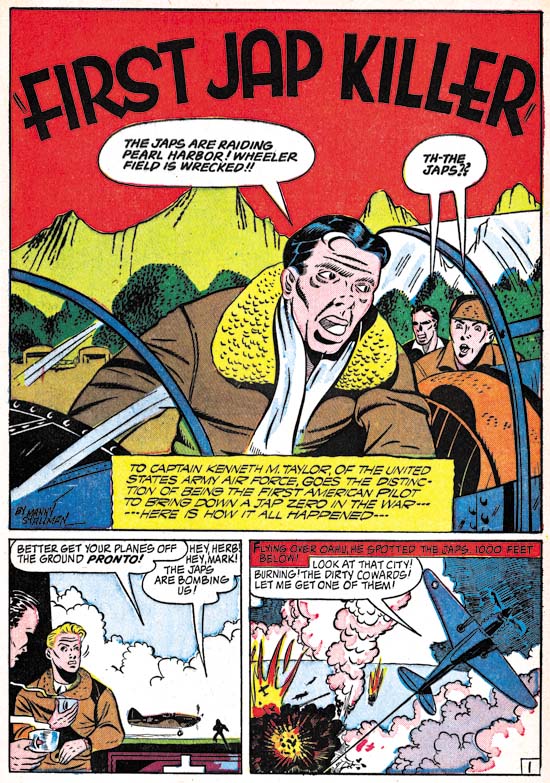

Captain Aero v. 4 n. 3 (#17) (October 1944) “First Jap Killer”, art by Manny Stallman

Will the real Manny Stallman please stand up? Well that was how I felt after examining three distinct styles from stories of the late ’40s and ’50s all of which were signed as Manny Stallman (Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 of It’s A Crime, and Atlas Tales). The Captain Aero pieces signed by Stallman could be considered a fourth style. However, in this case that is not particularly surprising because a common theme of this post is how much the work of these artists changed over the years.

Captain Aero #21 (December 1944) “Next Door to Death” page 2, art by Manny Stallman

In his art for Captain Aero, Manny drew eyes with an almond shape; little indication of the tear ducts and the upper and lower eyelids having curves that are almost mirror images. Despite a separation of over 10 years, similar eyes are found in the work that Stallman did for Atlas in the ’50s. In contrast, Almond shaped eyes are not found in any of the work done for Simon and Kirby. Further investigations will need to be made, but I am beginning to suspect that ghost artists were used for all the work that Stallman submitted to Simon and Kirby.

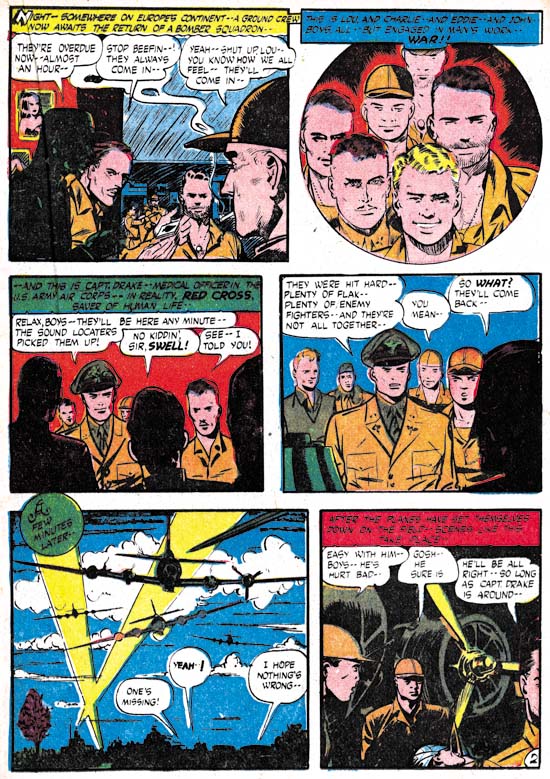

Captain Aero #21 (December 1944) “Red Cross” page 2, art by John Giunta

John Giunta appears in the same issues of Captain Aero as Manny Stallman. The team of Giunta and Stallman signed also two works for Simon and Kirby (Chapter 9 of The Art of Romance, and Chapter 7 of It’s A Crime). Mark Evanier’s in his obituary for Manny Stallman states that Stallman and Giunta teamed up on a number of occasions. Even though there are no jointly signed works in Captain Aero, their mutual presence does suggest the connection between the two artists extended at least back into 1944. John did a couple of Mighty Mite stories for Captain Aero but that feature called for a cartoon style that makes it difficult to compare with his Simon and Kirby art. Such comparisons are not easy even with his “Red Cross” story, however the eyebrows are rendered in a rather distinctive manner that has some correspondence to those drawn in Giunta’s S&K work.

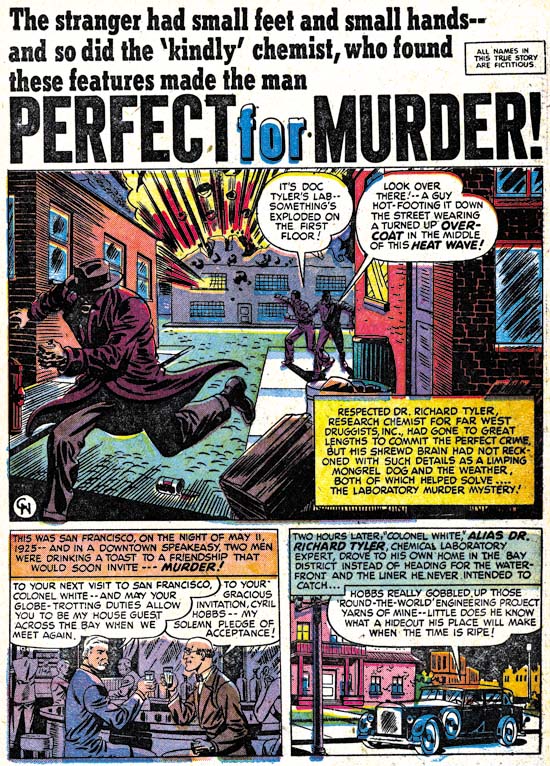

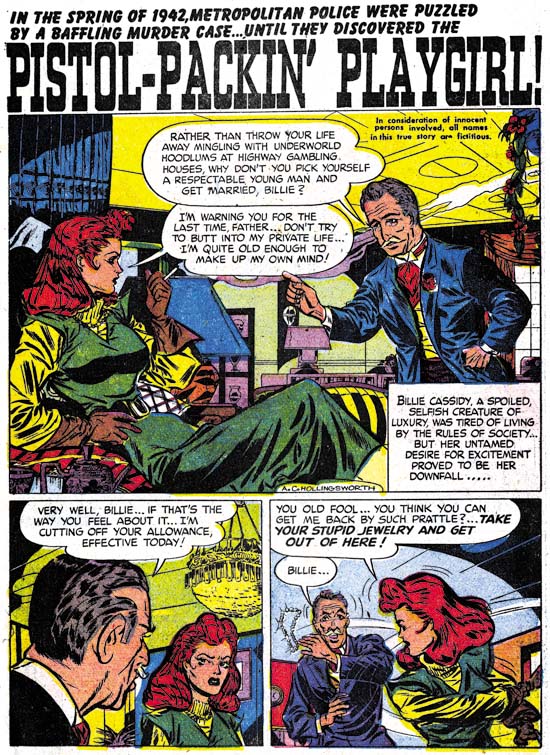

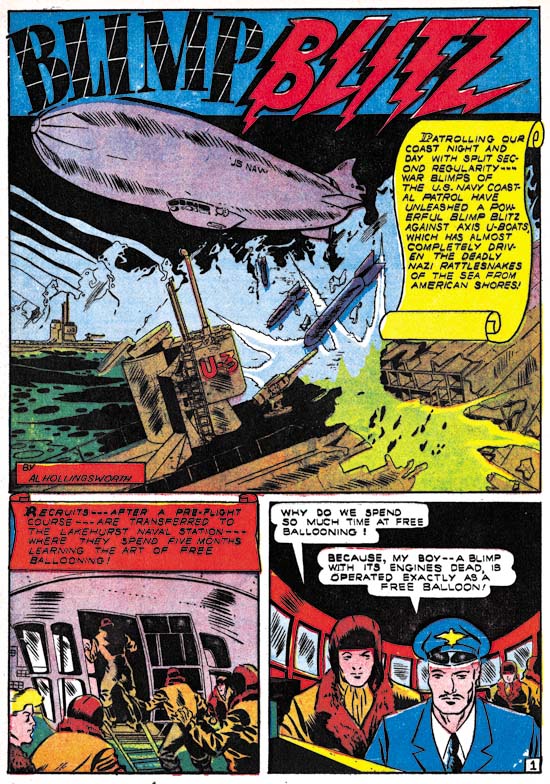

Captain Aero #23 (August 1945) “Blimp Blitz”, art by Al Hollingsworth

The African American comic artist, Alvin C. Hollingsworth, only worked for Simon and Kirby for a short time (It’s A Crime Chapter 6 and Chapter 7) but left a lasting impression on Joe Simon who remembers him to this day. It is not the talented Hollingsworth that we saw in the art produced for Joe and Jack, but a much more primitive, earlier version. Still, it is nice work.

Captain Aero #25 (February 1946) “The Wail of the Whaler” page 4, art by George Gregg

George Gregg’s Captain Aero work is cruder then what he did for Simon and Kirby (Chapter 5, Chapter 7, and Chapter 9 of The Art of Romance) but, at least on this page, more fun. I just love the multiple images of the fist in the first panel, which certainly is not how Jack Kirby would portray a slug fest! The art on a whole is more unrefined then the admittedly still not very sophisticated form of his Simon and Kirby work. Frankly, I prefer this more primitive but energetic version of George Gregg.

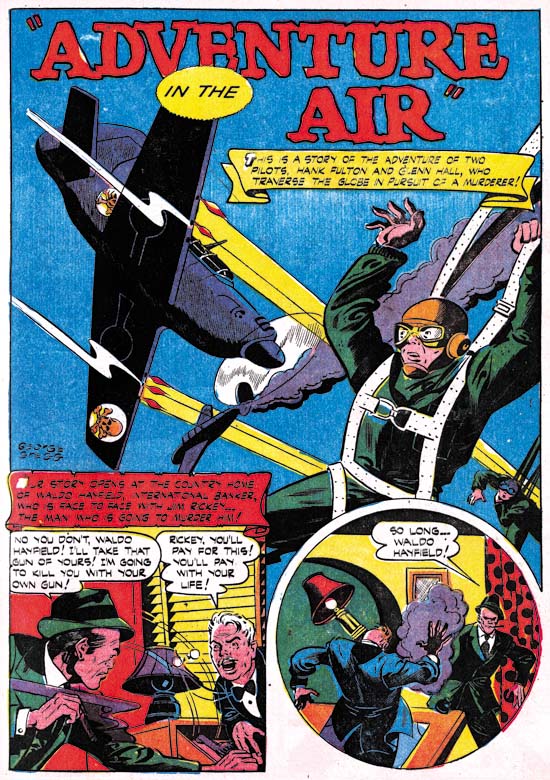

Captain Aero #26 (August 1946) “Adventure in the Air”, art by George Gregg

Did George Gregg undergo a prodigious advancement since the last issue? The Gregg’s art in Captain Aero #26 is much more realistic then issue #25. Actually the art may have been done months apart since about six months separate the two issues. Captain Aero #26, however, was the final issue so there is a good possibility that its publication was delayed and that the art was actually done much earlier. Whatever the reason, “Adventure in the Air” sports a more realistic style.

Captain Aero #23 (August 1945) “Interceptor Command”, art by Carmine Infantino

We have seen Carmine Infantino’s work not only for Simon and Kirby’s Charlie Chan (It’s A Crime, Chapter 8) but earlier for Hillman’s comics. Simon and Kirby were just freelance artists for Hillman and not producing the comics, so Carmine was not working for Joe and Jack at that time. Infantino was about 20 years old when he did “Interceptor Command”. That may seem young but Carmine first published work was done when he was about 16 years old and still in high school. The splash shown above looks like the work of a mature artist; nicely composed with solid inking. I like it better then what Carmine did for Hillman a couple of years later and inked by Bernard Sachs. However the splash is misleading as the story art is much sketchier.

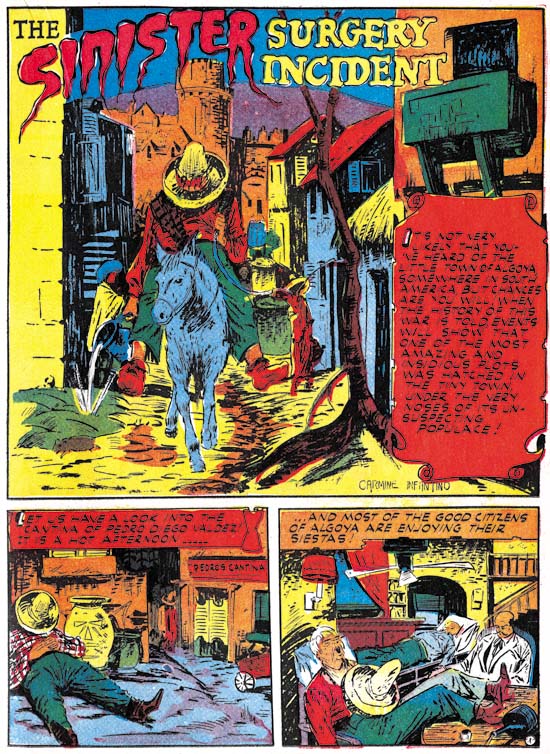

Captain Aero #26 (August 1946) “The Sinister Surgery Incident”, art by Carmine Infantino

A better idea of Infantino’s story art can be seen in the bottom panels of the splash for “The Sinister Surgery Incident”. While it has its interesting points, the art is somewhat sketchy. More then the art itself, I am impressed with the amount of progress that it indicates Infantino made over the years. Once again I suspect that a good study of the evolution of Carmine Infantino’s art over his life would be highly rewarding. Unfortunately it is a study that requires much more then my current resources and so it is a study I do not think I could ever attempt.

I plan to return to my ongoing serial posts, The Art of Romance and It’s A Crime, in a few weeks. But it was never my intention for those serial posts to monopolize the Simon and Kirby blog. Still it has been rewarding, at least for me, to concentrate on them (I only wish I had started It’s A Crime earlier and kept the two serials synchronized). In the mean time I want to explore a little of the earlier work by Simon and Kirby studio artists. Having here touched on examples of various studio artists found in Captain Aero, next week I plan to have a short post on a few earlier works by Leonard Starr and the week after that a longer one on early Mort Meskin with a little Jerry Robinson thrown in.