(Real West Romance #1 – #7, Western Love #1 – #6)

The theme of this chapter is one that I have touched on before in relationship to some work from Young Romance. Rather then repeat myself over and over again in the examples below I will summarize my argument here. There are five basic ways that some story art might have an incomplete resemblance Jack Kirby’s work; the art may have been done by an artist that was influenced by Kirby; the artist may have swiped from Kirby; Kirby acting as an art editor may have altered another artist’s work; the inker may have deviated from the original pencils by Kirby; or Kirby did layouts that were finished by another penciler/inker. The first three can easily be distinguished from the other two by not being consistently present throughout the story. However distinguishing between the effects of a heavy handed inker or an artist working from Kirby layouts presents more of a problem. In the end it is a judgment call which is probably based in part on how the person making the call feels about the way inkers at the time went about their work. If you believe that inkers working for Simon and Kirby felt that they should impart their own vision on Kirby’s pencils (such as certainly was the case in the silver age) then you are likely attribute stories that do not look like typical Kirby to a heavy handed inker. If, like me, you doubt that an inker would take liberties on tight pencils provided by Kirby (who after all was their boss) then untypical Kirby stories would be better explained as due to an artist working from Kirby layouts. The difference between the two possibilities really is not that great because in these cases the second artist appears to have been the inker as well. Nonetheless I like to make the distinction because there really does seem to be two bodies of work. One group of work is easily identified as by Jack Kirby with all of his characteristic traits no matter who did the inking (the unadulterated Kirby). The other may not always be so readily identified and has unusual traits (unusual at least for Kirby).

I remember that during the silver age Kirby was sometimes listed as having provided layouts while another artist would get the credit for the penciling or finishing. I believe this is just as unfair as the credit Jack sometimes got for plotting while another (Stan Lee) would be credit with the writing. Plotting a story would normally be considered part of writing it just as laying out a story would generally be included in the drawing of a story. Separating plotting from writing or layouts from pencils is fundamentally unfair. In Jack Kirby’s case it is particularly egregious because some of his margin notes ended up in actual dialog and also some of his layouts would be quite tightly rendered in places. Therefore in cases where Jack provided layouts I prefer to credit the pencils to both Jack and the other artist. Unfortunately I have never been able to identify who the finishing artists were.

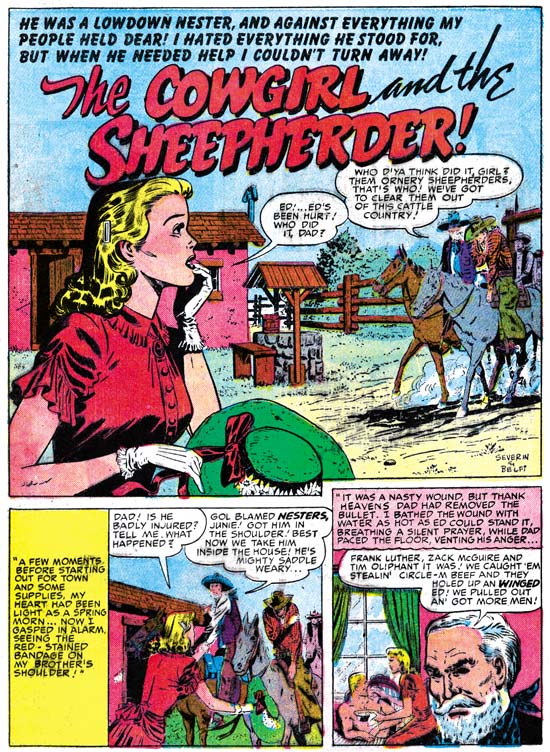

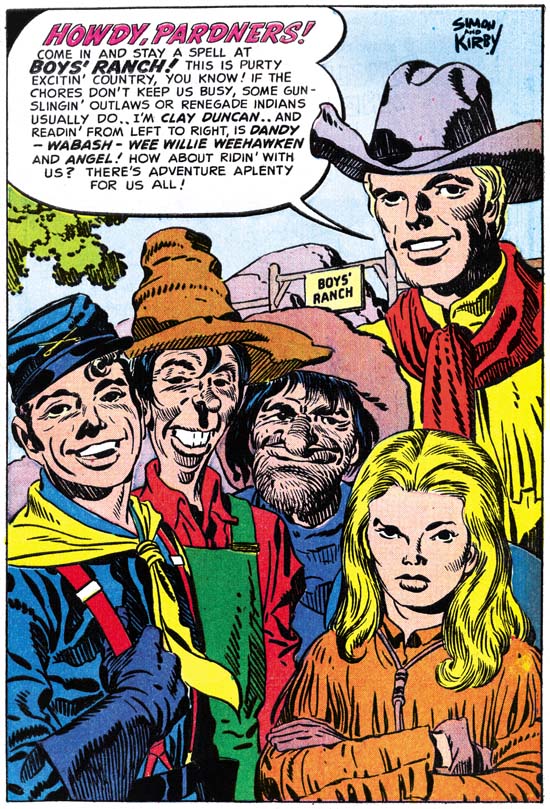

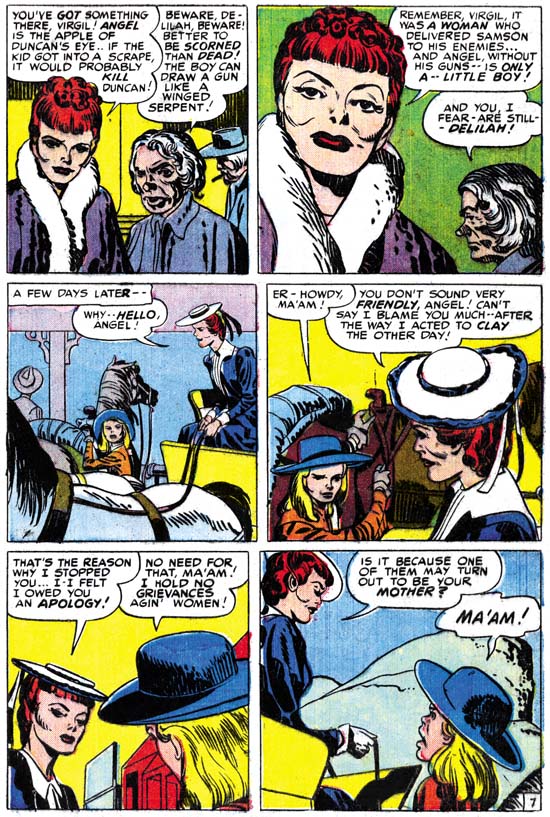

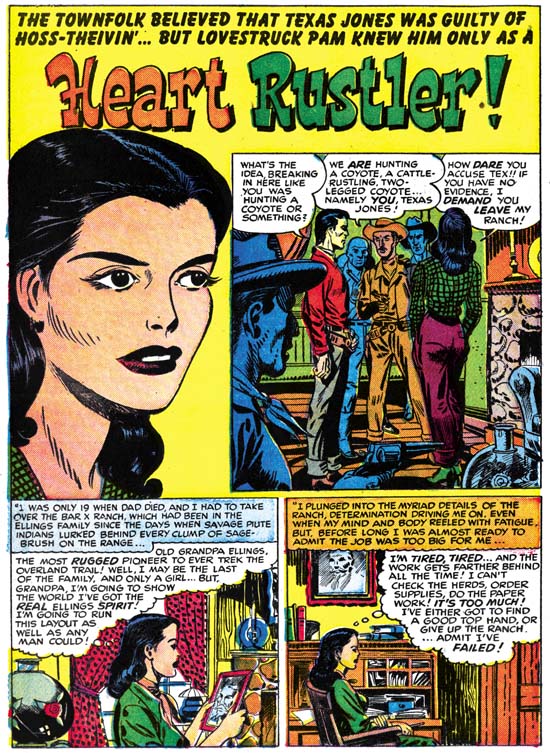

Real Western Romance #1 (April 1949) “Heart Rustler”, art by Jack Kirby and unidentified artist

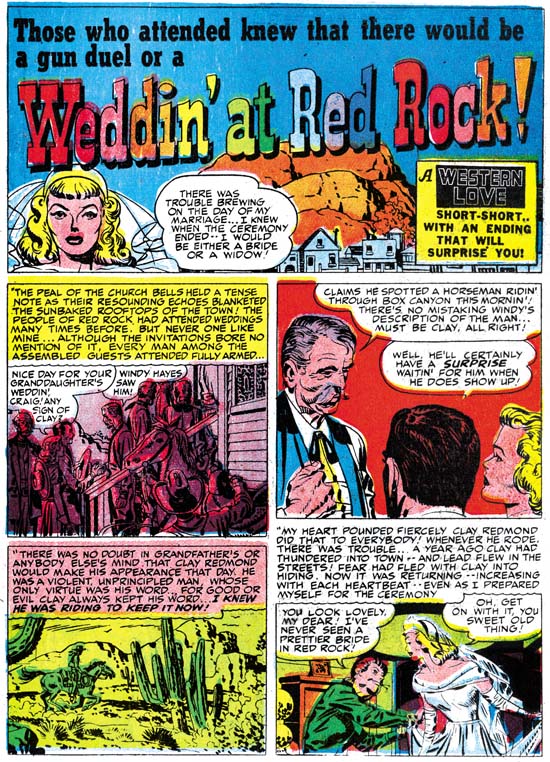

The Jack Kirby Checklist cites “Heart Rustler” as being inked, but not penciled, by Jack Kirby. Simon and Kirby’s business was not so much creating comic books as producing them. So it is easy to imagine circumstances where Jack Kirby could be called on to ink someone else’s pencils. I do not know about the reader, but I would love to see how Kirby would ink another artist. So I look at stories like “Heart Rustler” with much interest. However when I examined this story I was disappointed, it was clearly not inked by Jack. Yes there are some places that exhibit some features of Studio style inking. There are some abstract shadows in each panel that are created using a very blunt brush (see my Inking Glossary for explanations of the terms I use to describe inking techniques). Those in the splash panel and first story panel could even be described as having an arced edge. It is probable that Jack or Joe added them. More important are the spotting that is done in a way that Kirby would not have done it. The man blocked out in blue on the left edge of the splash panel has a hat casting a shadow formed by simple hatching; I have never seen Kirby do that. It may be a little hard to make out in the image I supplied but the lower legs of the woman in the same splash panel are shadowed with nearly vertical lines; again this is not an inking technique that Jack used. None of the clothing folds look like Jack’s brush. In fact the shoulder of the woman in the first story panel has a couple of odd blunt spots; one of which is attached to a then line as if it was a leaf on a drooping stem. Kirby would sometimes use similar blots on the edge of a limb as a way of indicating a shadow but he never placed them isolated as done by this inker. Similar problems can be found throughout the story. So I repeat Jack Kirby did not ink this story other then some possible touch ups.

Was the attribution found in the Jack Kirby Checklist just completely unreasonable? No, I think I can understand how it came to be. Look at the face of the woman in the splash. She seems to me to have a very Kirby look to her. Kirby’s hand is a bit harder to see on the rest of the page although I feel it can be seen in the armed gunman in the splash panel. I also believe I can spot Kirby’s touch in the other pages of the story. Further the entire story seems to be laid out in a manner typical for Jack Kirby. I suspect that source of the inking attribution in the Jack Kirby Checklist noted the Kirby look to the story and assumed that it was achieved by Jack inking the piece. Since the brush work itself shows that Kirby was not the inker another explanation must be advanced. The explanation I would give is that Kirby did the layouts for this story. It is apparent that when Jack did layouts the pencils would be tighter in some parts (like the face of the woman in the splash) while other places it would be rougher. Another artist would then tighten up the work and then ink it or perhaps tighten it up while inking.

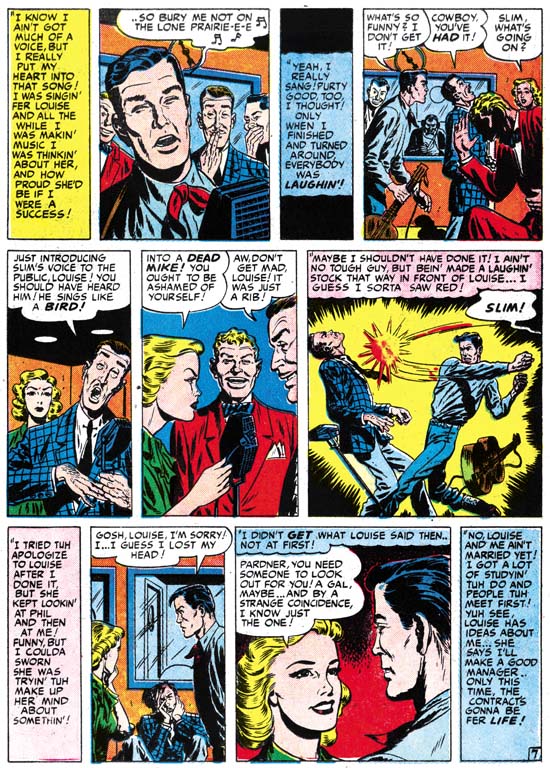

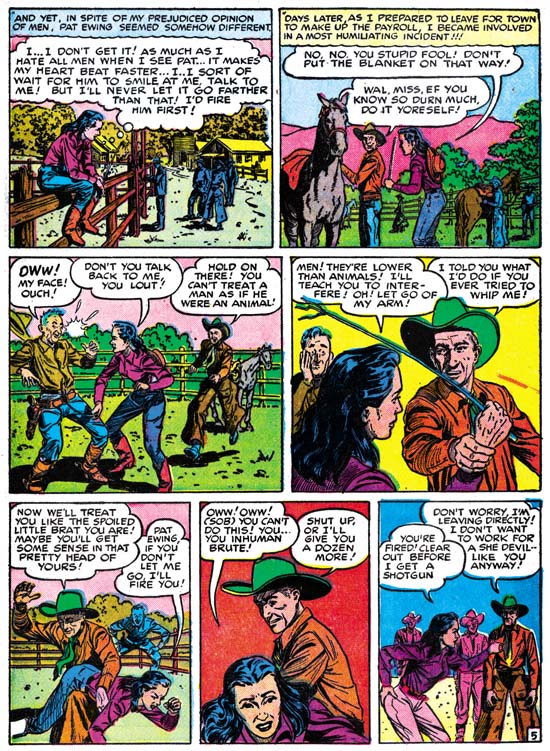

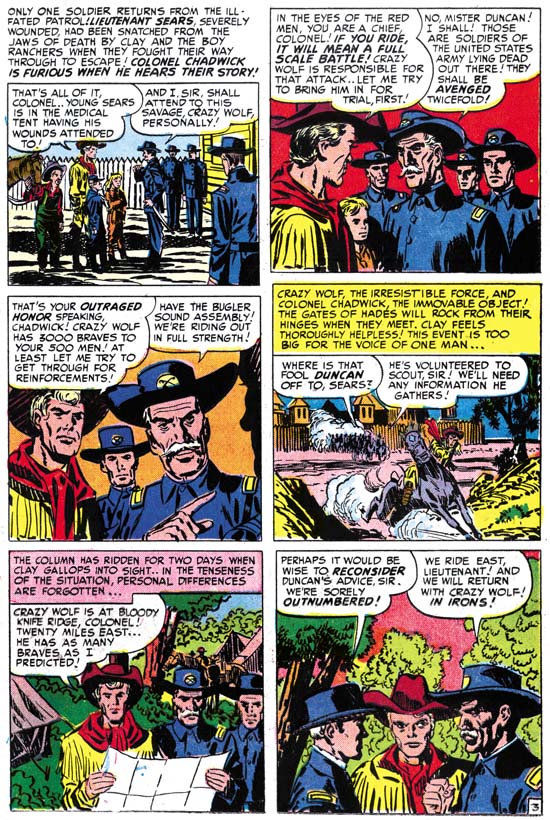

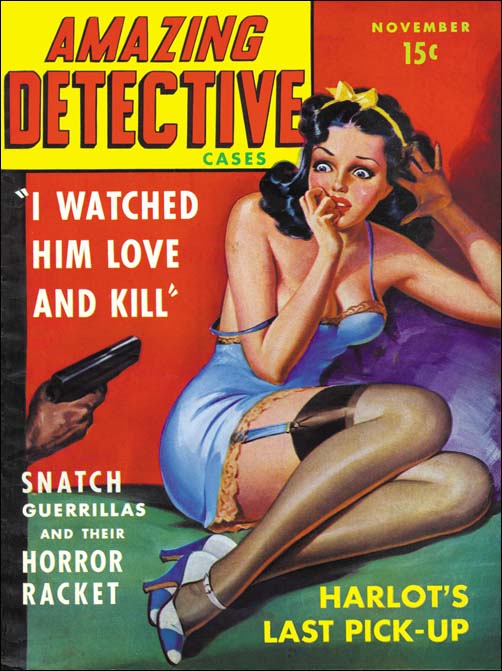

Real Western Romance #3 (August 1949) “Our Love Wore Six-Guns”, art by Jack Kirby and unidentified artist

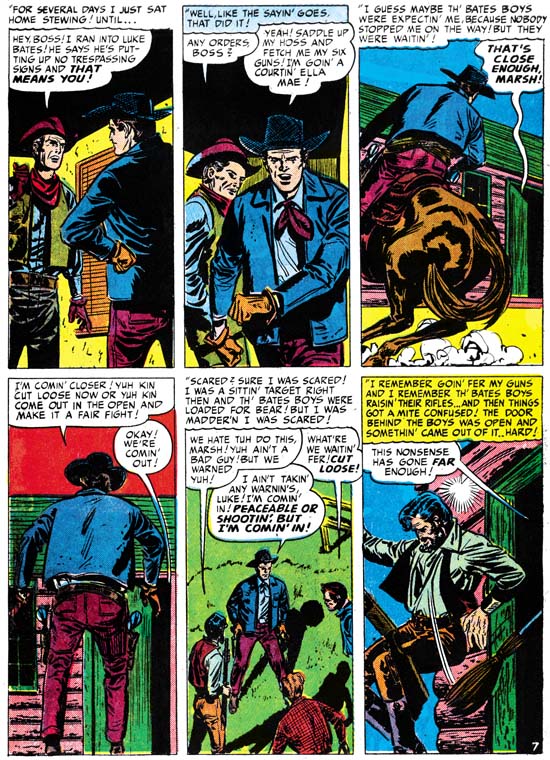

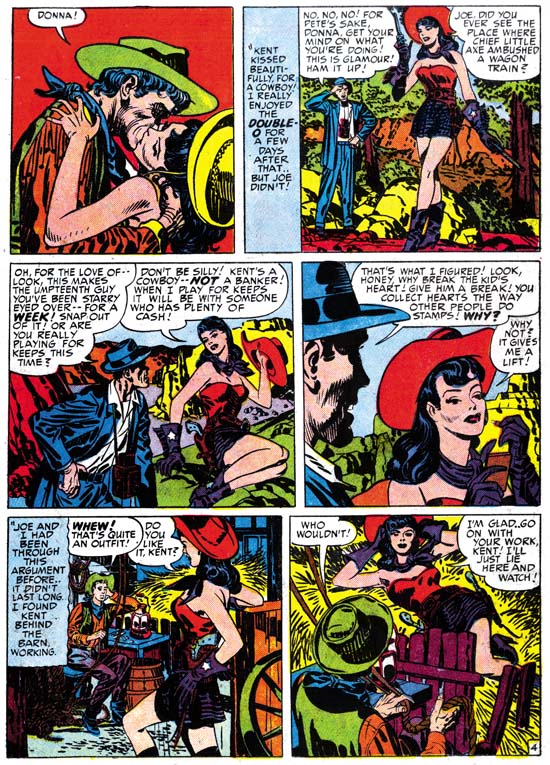

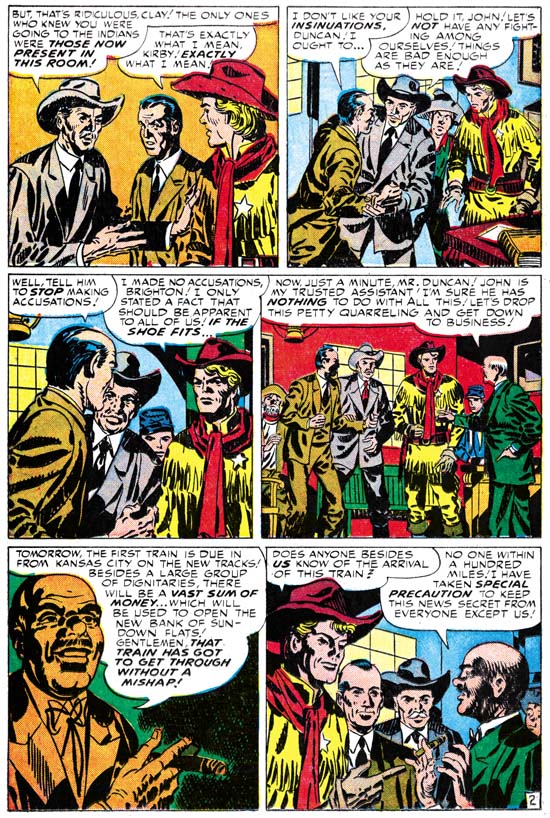

Another story identified by the Jack Kirby Checklist as inked but not drawn by Jack Kirby is “Our Love Wore Six-Guns”. Here is a case where the inking is actually done in a manner even further from that used by Kirby then in “Heart Rustler”. Nothing looks like Studio style inking. The clothing folds are typically long and narrow very unlike what Jack was doing at this time. It may be less obvious in “Our Love Wore Six-Guns” then in “Heart Rustler” but there are some faces that look like they had the Kirby touch; for instance the woman in the page’s last panel. These Kirby-like portions occur too frequently throughout the story to be explained as either swiping by the artist or art editing by Jack. The man is just as consistently un-Kirby like in my opinion. I find it hard to believe that an inker would have produced the man’s face in this way had he been inking over tight pencils by Jack. The story layout does seem to have consistently been done in a way appropriate for Kirby. So my conclusion is once again Jack provided layouts and another artist finished and inked them. The inking style used in this story does not match that for “Heart Rustler” so I believe different artists were used for the two stories.

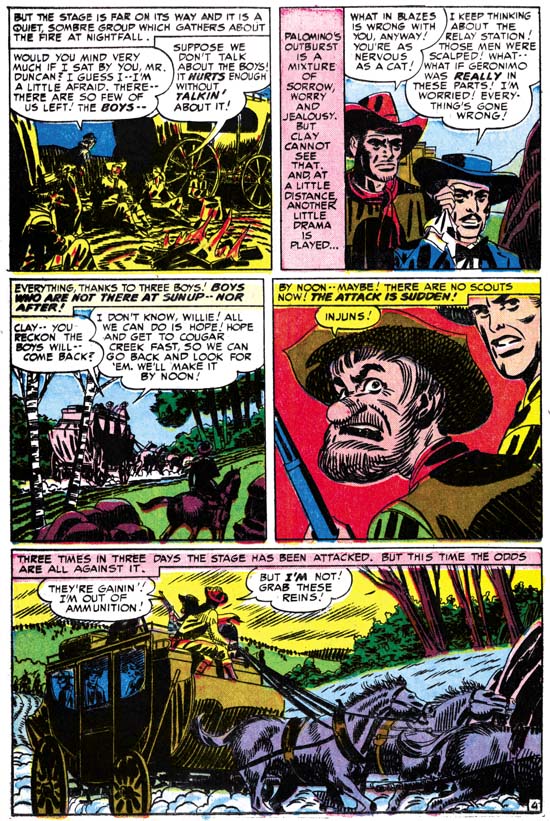

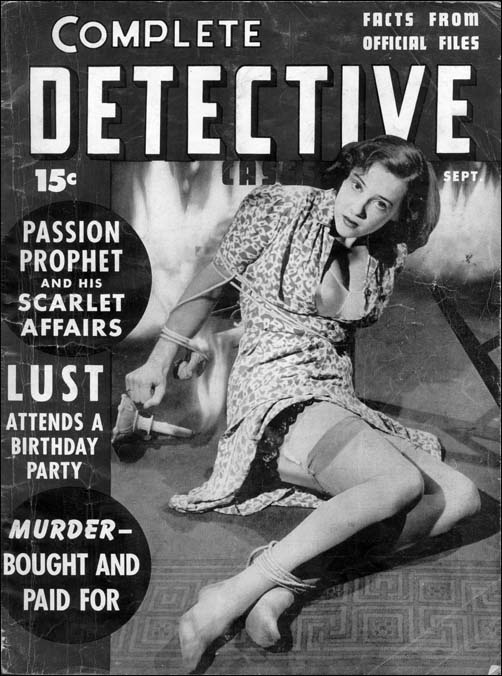

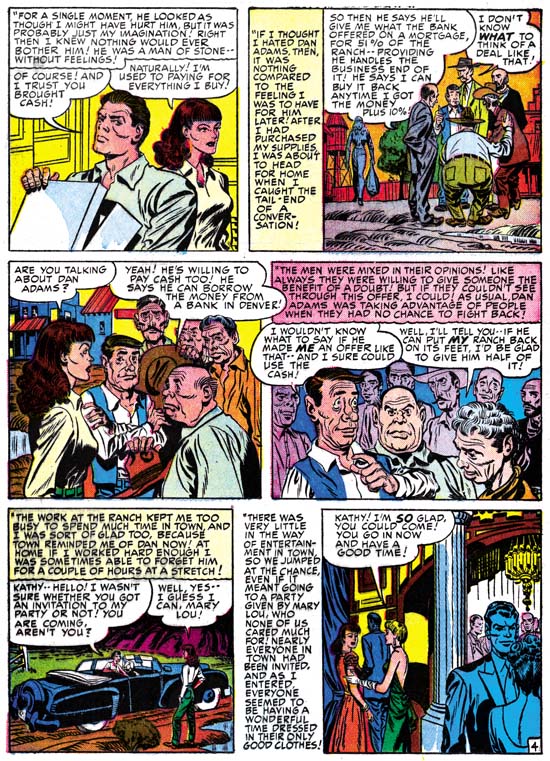

Western Love #2 (September 1949) “Kathy and the Merchant” page 4, art by Jack Kirby and unidentified artist

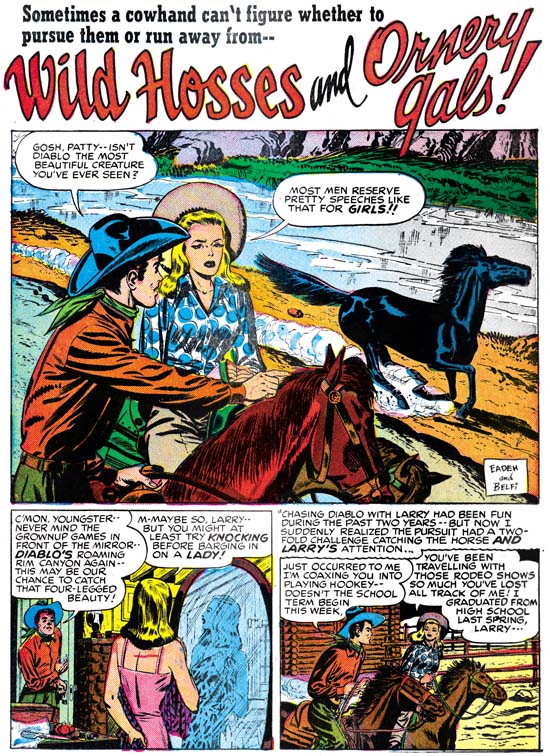

To be honest I am not very impressed with either of the two artists who worked on the Kirby layouts for the two stories I discussed above. Because of the low quality of the work usually found on Kirby layouts, I believe the layouts were generally provided when Simon and Kirby felt it was necessary to employ the use of artists of lesser talent, perhaps even studio assistants. However there are exceptions such as “Kathy and the Merchant”. The group of men in panels 2 to 4 is, in my opinion, nicely done. I also do not think their higher quality was due to tighter pencils. To my eyes they have a blend of Kirby and non-Kirby elements. Page 4 is typical of the story so swiping or editing can be eliminated as explanations. I can understand if others believe that Jack did the pencils that were just inked by another, but I prefer to think that Jack supplied layouts not tight pencils. I will say that the Jack Kirby Checklist credits Joe Simon with the inking but I feel that is clearly wrong. The brushwork is much too fine in this story to be the work of Joe.

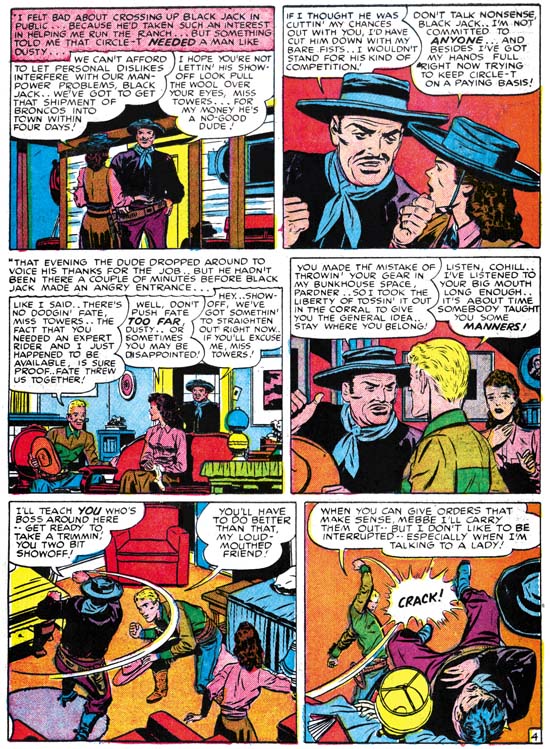

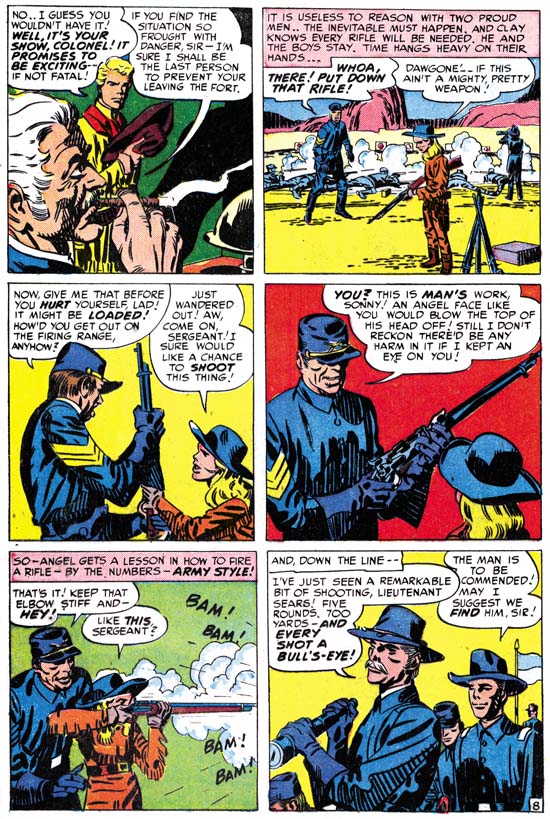

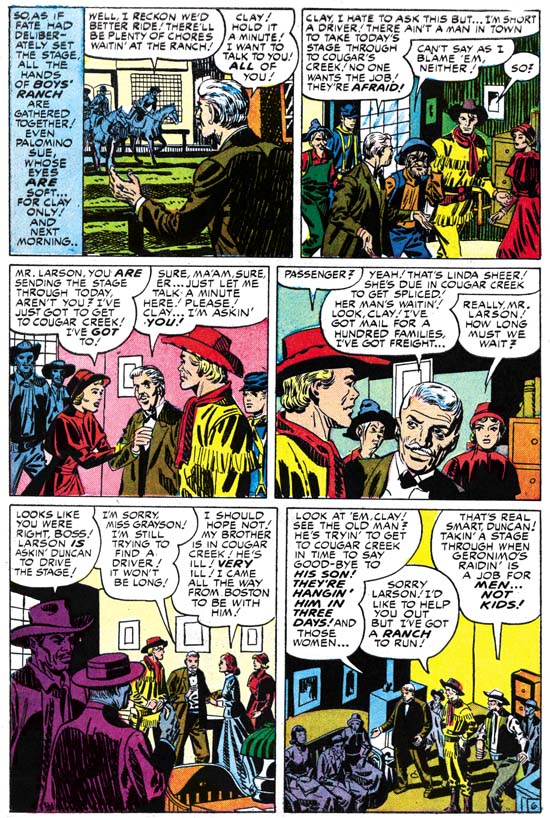

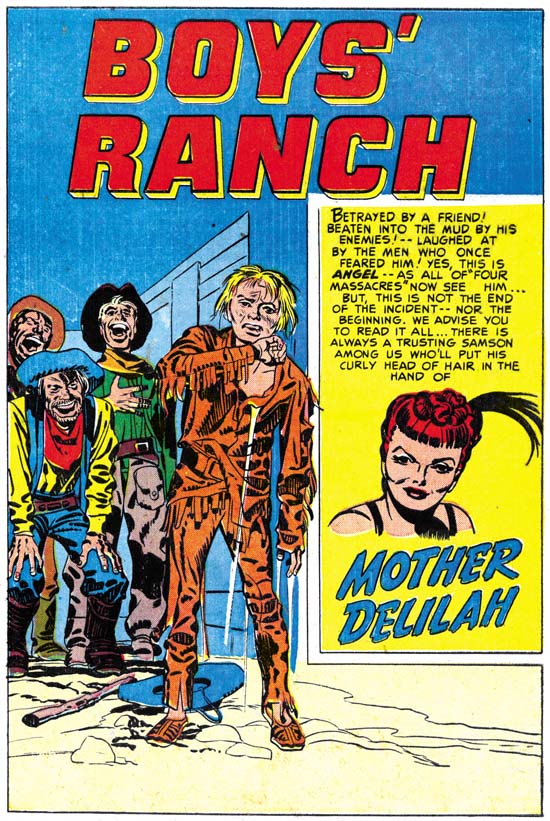

Real Western Romance #4 (October 1949) “Perfect Cowboy” page 4, art by Jack Kirby and unidentified artist

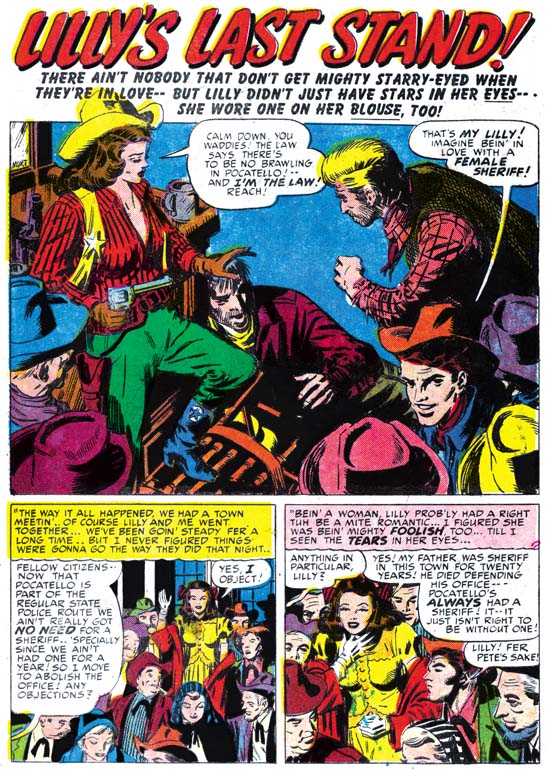

I think “Perfect Cowboy” also falls into the category of Kirby layouts. The splash may have been particularly tighter and was not inked by the same artist as the rest of the story. The story inking is very interesting. At a glance it appears to be Studio style brushwork. Certainly that was what the inker was attempting. But this is not Joe Simon’s inking as suggested by some. The picket fence crosshatching only superficially resembles Jack or Joe’s brush. The pickets have a distinct pointed end and progressively widen through most of their length unlike the more uniform width found in Kirby, Simon or even Meskin’s use of the Studio style. I am not sure I would call it true picket fence, but simple crosshatching is applied to the dust cloud in panel 3 which is unlike anything I have seen by an inker working in the Studio style. However the most unique technique of this inker is his applying of picket fence crosshatching to the hair of the woman as best seen in the last two panels of this page. The pickets are placed in the same direction as would be expected for the hair and therefore the rails are at odds to the flow of the hair. This is all meant to suggest shadows formed on the lower parts of the waves and curls but the result is decidedly unnatural looking. I do not remember seeing this spotting of hair ever being repeated in Simon and Kirby productions.

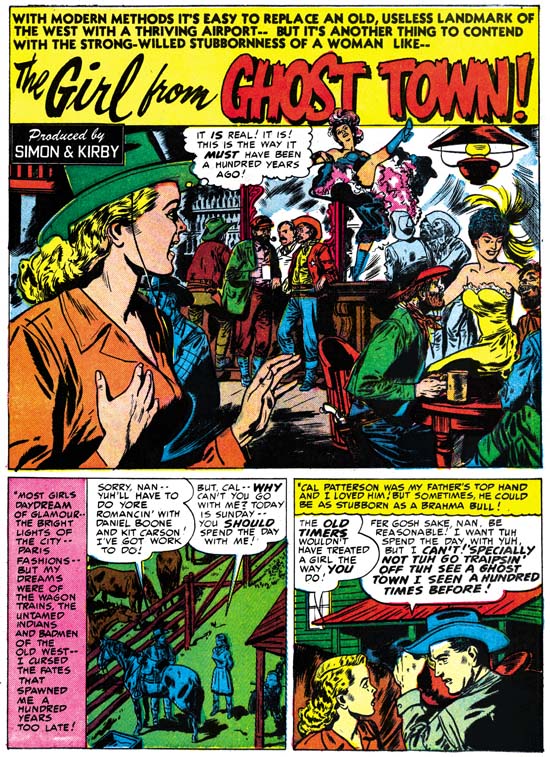

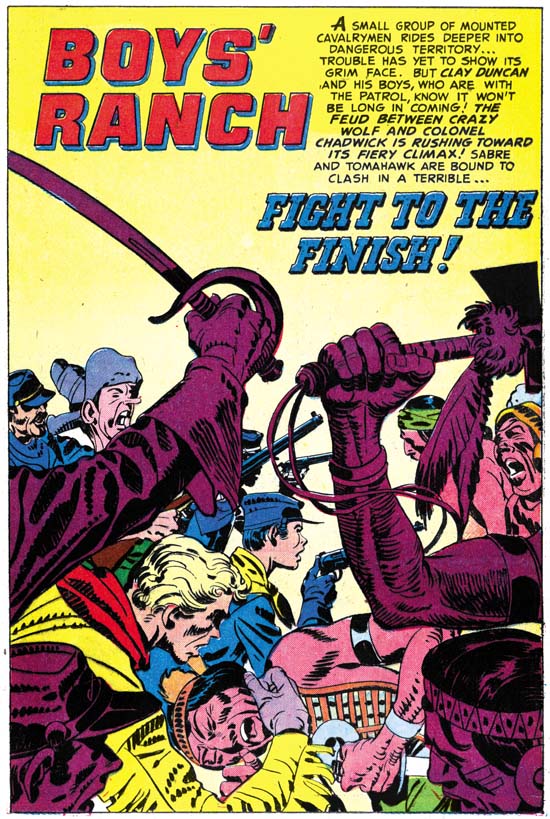

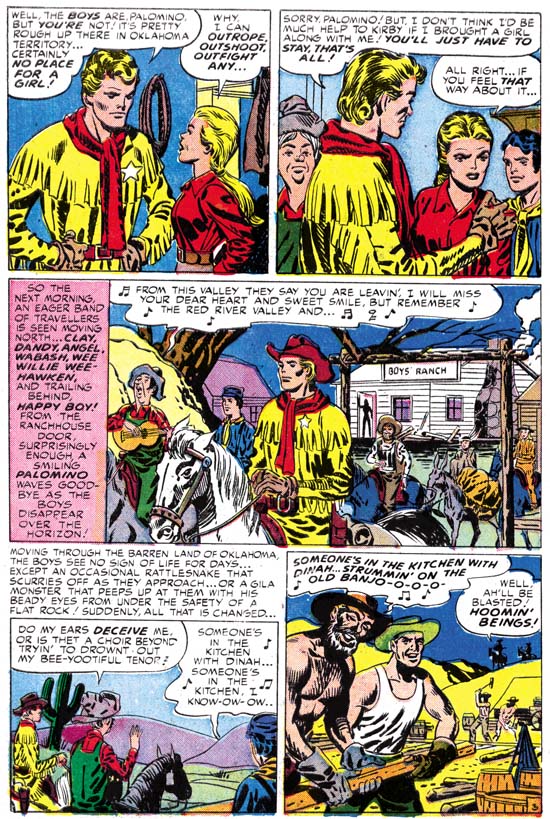

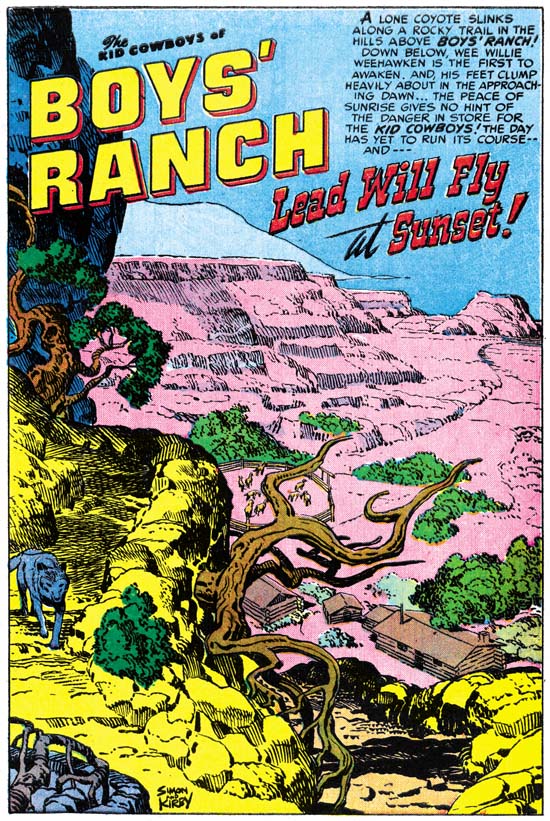

Real Western Romance #7 “Loves of a Navajo Princess”, art by Jack Kirby and unidentified artist

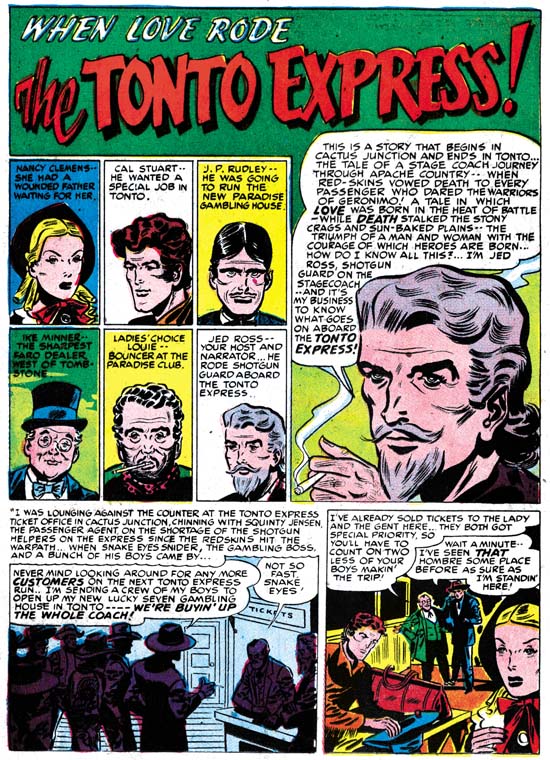

The final story that I will cover is a tough call. The two Indians in the splash panel were clearly done by Jack Kirby. The Studio style inking that the left part of the panel shows almost convinced me that this was an example of Jack as art editor fixing up the splash. However close examination showed that the same inking style was used on the rest of the splash. Actually the entire story is done in Studio style inking; picket fence crosshatching, drop strings, abstract arc shadows, the works. In fact the inking job is truly well done but it just does not look like Kirby’s brush. The biggest giveaway is the cloth folds which have a distinct tendency for elongated folds in some places and irregular blots in others. Nowhere else does the art look quite as pure Kirby as the splash but there are more then enough places that have Jack’s touch to convince me that it was his layouts. But like I said it is a tough call and I am not sure many will agree with me, certainly the Jack Kirby Checklist does not.

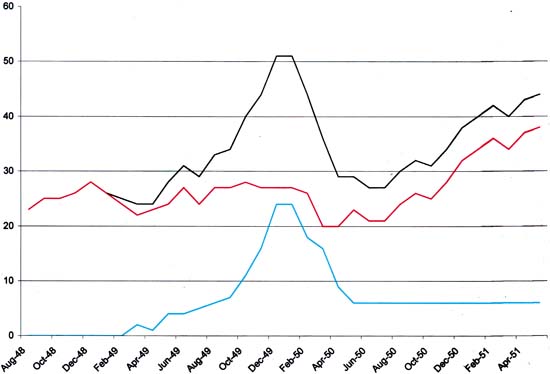

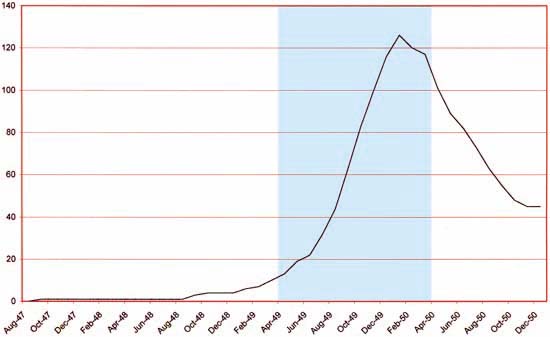

This chapter concludes the western romance section of The Art of Romance. I have added to my sidebar checklists for Real West Romance and Western Love. Cowboy love was an interesting experiment but it just was not a very successful one. The love glut resulted in the cancellation of a lot of romance comics including the western subgenre. However it would not be correct to blame the demise of the western romance on the love glut. Despite all the cancelled love titles there must have been enough profits during the love glut to convince at least the major publishers to continue to produce a significant number of titles. In contrast none of the publishers decided to continue the western romance titles. The effects of the love glut on the romances that Simon and Kirby produced for Prize was very divergent. Real West Romance and Western Love must not have sold well as they were cancelled just after the peak of the love glut. Young Romance and Young Love not only seemed to weather the love glut but to flourish. But that will be discussed in future chapters of The Art of Romance.

Chapter 1, A New Genre (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 2, Early Artists (YR #1 – #4)

Chapter 3, The Field No Longer Their’s Alone (YR #5 – #8)

Chapter 4, An Explosion of Romance (YR #9 – #12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 5, New Talent (YR #9 – 12, YL #1 – #4)

Chapter 6, Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 7, More Love on the Range (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 8, Kirby on the Range? (RWR #1 – #7, WL #1 – #6)

Chapter 9, More Romance (YR #13 – #16, YL #5 – #6)

Chapter 10, The Peak of the Love Glut (YR #17 – #20, YL #7 – #8)

Chapter 11, After the Glut (YR #21 – #23, YL #9 – #10)

Chapter 12, A Smaller Studio (YR #24 – #26, YL #12 – #14)

Chapter 13, Romance Bottoms Out (YR #27 – #29, YL #15 – #17)

Chapter 14, The Third Suspect (YR #30 – #32, YL #18 – #20)

Chapter 15, The Action of Romance (YR #33 – #35, YL #21 – #23)

Chapter 16, Someone Old and Someone New (YR #36 – #38, YL #24 – #26)

Chapter 17, The Assistant (YR #39 – #41, YL #27 – #29)

Chapter 18, Meskin Takes Over (YR #42 – #44, YL #30 – #32)

Chapter 19, More Artists (YR #45 – #47, YL #33 – #35)

Chapter 20, Romance Still Matters (YR #48 – #50, YL #36 – #38, YB #1)

Chapter 21, Roussos Messes Up (YR #51 – #53, YL #39 – #41, YB #2 – 3)

Chapter 22, He’s the Man (YR #54 – #56, YL #42 – #44, YB #4)

Chapter 23, New Ways of Doing Things (YR #57 – #59, YL #45 – #47, YB #5 – #6)

Chapter 24, A New Artist (YR #60 – #62, YL #48 – #50, YB #7 – #8)

Chapter 25, More New Faces (YR #63 – #65, YLe #51 – #53, YB #9 – #11)

Chapter 26, Goodbye Jack (YR #66 – #68, YL #54 – #56, YB #12 – #14)

Chapter 27, The Return of Mort (YR #69 – #71, YL #57 – #59, YB #15 – #17)

Chapter 28, A Glut of Artists (YR #72 – #74, YL #60 – #62, YB #18 & #19, IL #1 & #2)

Chapter 29, Trouble Begins (YR #75 – #77, YL #63 – #65, YB #20 – #22, IL #3 – #5)

Chapter 30, Transition (YR #78 – #80, YL #66 – #68, YBs #23 – #25, IL #6, ILY #7)

Chapter 30, Appendix (YB #23)

Chapter 31, Kirby, Kirby and More Kirby (YR #81 – #82, YL #69 – #70, YB #26 – #27)

Chapter 32, The Kirby Beat Goes On (YR #83 – #84, YL #71 – #72, YB #28 – #29)

Chapter 33, End of an Era (YR #85 – #87, YL #73, YB #30, AFL #1)

Chapter 34, A New Prize Title (YR #88 – #91, AFL #2 – #5, PL #1 – #2)

Chapter 35, Settling In ( YR #92 – #94, AFL #6 – #8, PL #3 – #5)

Appendix, J.O. Is Joe Orlando

Chapter 36, More Kirby (YR #95 – #97, AFL #9 – #11, PL #6 – #8)

Chapter 37, Some Surprises (YR #98 – #100, AFL #12 – #14, PL #9 – #11)

Chapter 38, All Things Must End (YR #101 – #103, AFL #15 – #17, PL #12 – #14)