Not long ago Daniel Best wrote a post on his blog about art recreations used in Marvel Masterworks (Original Art Stories: Marvel Masterworks Non-Original Artists). The gist of his comments was that he objected to Marvel’s use of recreated art in the Masterwork volumes. Mike Kelleher who does work for Marvel reprints posted a reply on the Marvel Masterworks Fan Site. The ensuing thread is typical of the sort of thing to be found in lists. It ranges from insightful discussion to meaningless name calling.

I have to give Mike Kelleher credit; he is open about what he has done. Apparently he felt quite justified in recreating art in some cases:

Marvel never gave me any instructions on how to recreate art. There is no way anyone could have known I redrew some of the pages on paper first before reconstructing them. My first 6-12 months of art recreation was done digitally, I then read an article somewhere ( might have been here but I don’t recall ) about how artists used to, and still do, literally redraw the pages for reprint purposes. Since I wasn’t happy with the results I was getting digitally, I decided to try drawing them (contrary to recent comments I am an accomplished, although unknown, artist :-). I’m still getting the feeling that some people are trying to attach sinister motives to this process, but there really are none.

He has an interesting post in the thread showing various stages in one of his reconstructions. Of particular interest to me was this statement:

Because Masterworks line art is printed 100% black just like the original comics, we need to digitally transform this image so that there is no grey. This is problem 1. There is no setting that will fill in the areas where the ink was light or dropped out completely. After playing with the adjustments for a few minutes I have decided that this is the best result I can get…

This explains the source of many of Marvel’s problems. Restricting the black plate to just line art was common in the original comics but is not typical of modern printing methods. In my opinion Marvels use of this technique in their reprints unnecessarily complicates the restoration process. With the level of correction that must be done the final results can be anything from a restoration to a recreation, depending on the person doing the work.

I found another of Mike Kelleher’s comments interesting:

Final points– All reconstructed artwork ( and most done from scans of stats and original art ) have some level of redrawn lines. Reality. Period.

This simply is wrong but I understand now why he believes it to be true. It is all back to that 100% black plate. Use a modern separation and you just cannot beat reproductions based on original art (assuming the original art is complete). I know original art is not always available so this is not a suggestion that Marvel take that approach.

In a previous thread on the same Marvel Masterworks Fan Site I learned from another that micro filch were used as the source for some of the golden age reprints. These micro filch were made many years ago but still occasionally show up in places like eBay. Their quality is fine for casual reading but as a source for reprints they leave much to be desired. Any reprint based on micro filch would almost certainly end up being a very poor recreation.

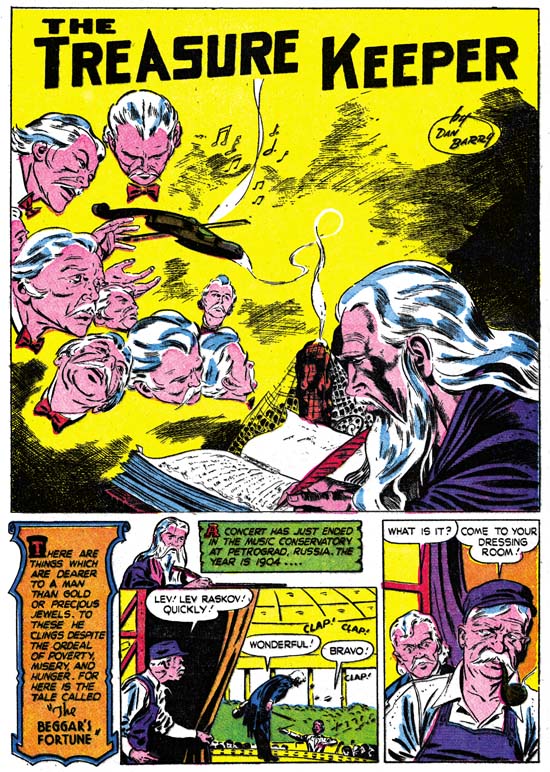

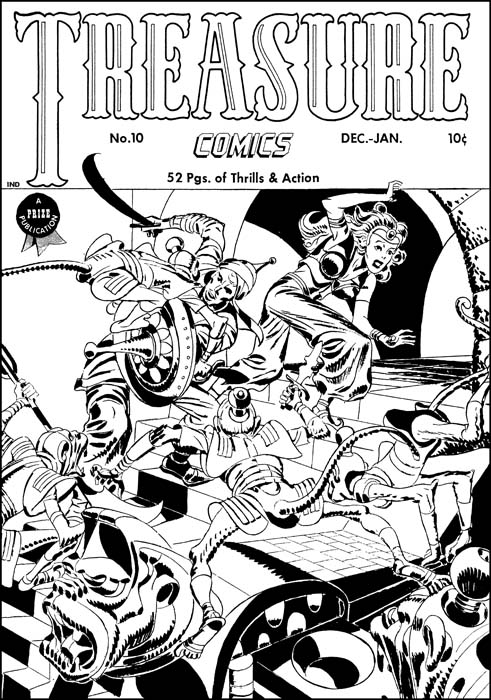

Treasure Comics #10 (December 1946), art by Jack Kirby

Years ago I decided digitally restore the line art for every Simon and Kirby cover. Even then I could not afford to chemically bleach the original comics. So I developed a method to remove the color using Photoshop. I must add that I am sure others have also figured how to do this on their own. Digitally bleaching is not as successful as with the use of chemicals so there was still a lot of work needed to clean up the final results.

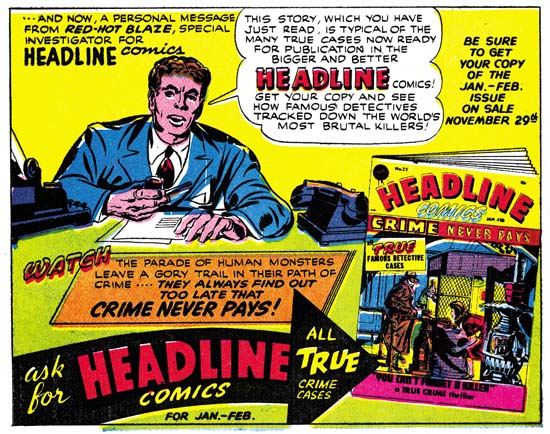

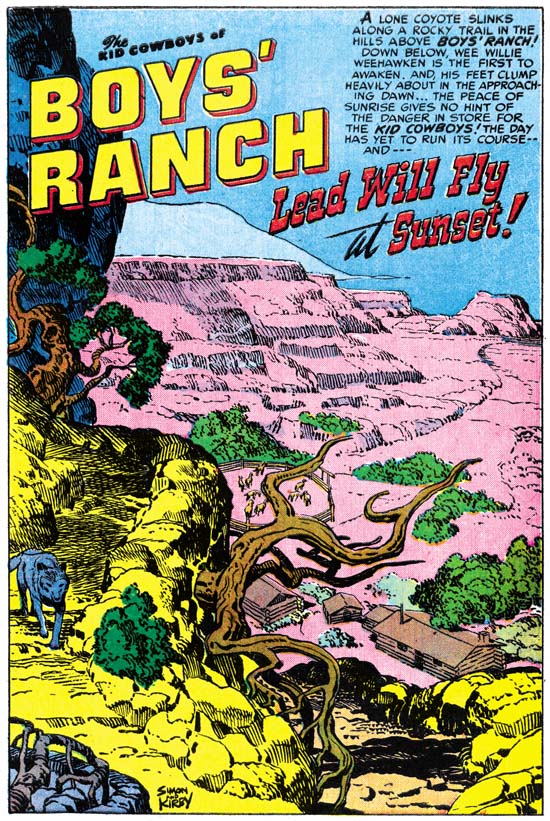

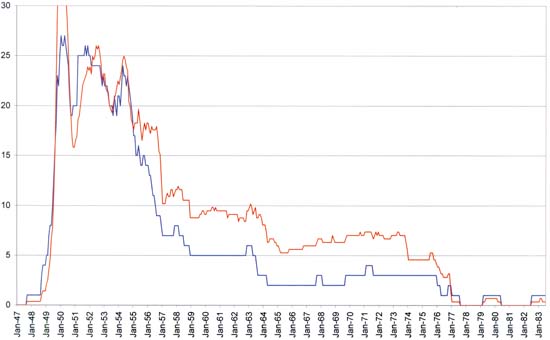

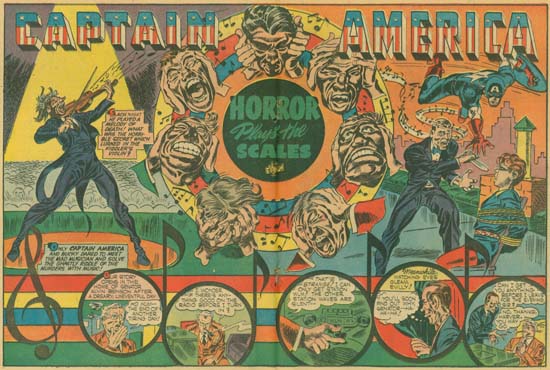

Captain America #7 (October 1941), art by Jack Kirby (original scan)

Larger view

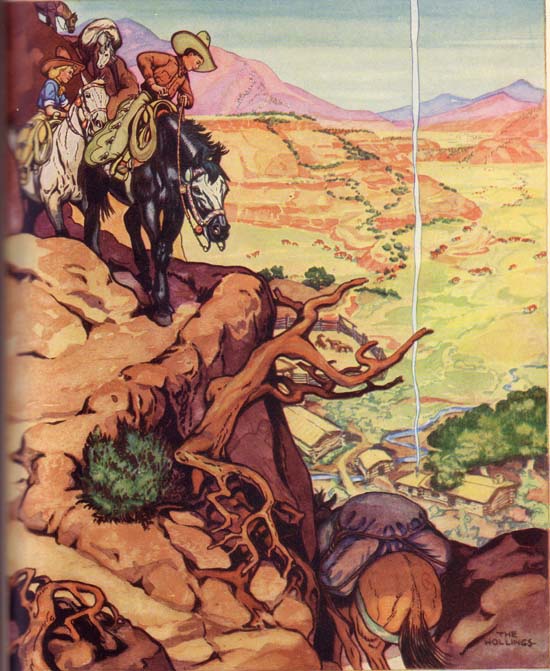

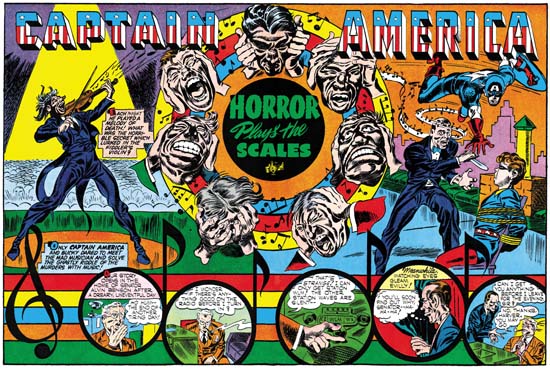

I did finish the project but in the end I came away with two basic realizations. One was this method required too much work. The second was that color really should be a part of the restoration process. I did not like Marvel reprints and felt there was a better and more accurate way of doing things. So once again I figured a process using Photoshop to do restoration. And yes I am sure others figured it out themselves as well. Usually I only post at least partially restored images in this blog, but now I will made an exception. The above image is an actually scan from a comic just as it came from my scanner. Below can be found my restoration based on that very scan. I was so pleased with my method that I once started a group (Digitizing Comic Books ). In that group I posted an explanation of some of my techniques. Well I do not think many got what I was trying to do so I never went past the basics. I am the moderator so there will be no problems if anyone wants to become a member. It is pretty much a dormant group but the archive still has my posts.

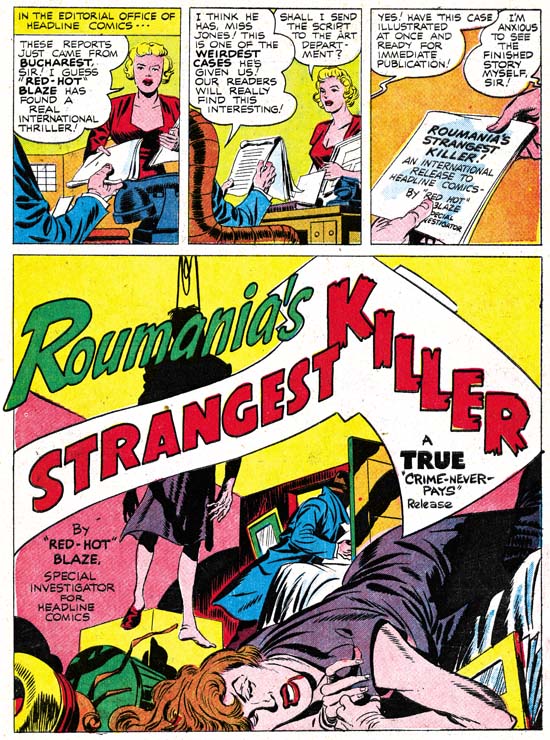

Captain America #7 (October 1941), art by Jack Kirby (restored)

Larger view

Is Marvel being dishonest by presenting recreations in a reprint volume? My original reaction was yes. Some on the thread have said that this was all well known facts. That it was not hidden in either Marvel interviews or posting on lists. I do not feel that is true discloser as not everyone reads those interviews or reads all comic book lists. So I pulled out my Marvel Masterwork volume of Daring Mystery. There in the table of contents they credit those who did the color and art “reconstruction”. Yes reconstruction is their word. My dictionary provides this definition of the word reconstruct:

“1) to construct again; rebuild; make over. 2) to build up, from remaining parts and other evidence, an image of what something was in its original and complete form”.

Well I feel the first definition is certainly valid for what Marvel has been doing (though not the second since the final result is nothing like the original form). So yes Marvel is being honest. I should have been more careful when buying these volumes because here reconstruct is another word for recreate.

There are those who honestly like Marvel’s approach and think the Masterwork volumes are the correct way to do reprints. They would not spend their money on what they would describe as just scans. There are also those who really are only interested in the characters and have little concern for studying the original artists and inkers. For all of them these Marvel Masterworks are a good deal. There are others who never did like what the glossy pages and flat colors of the Masterworks. There are also some who truly admire the earlier artists and want to see their art and not some recreation by a modern artist. For those the Masterworks just do not have the same value. I fall in this second category and I will be getting rid of the volumes I have and will not buy any more.