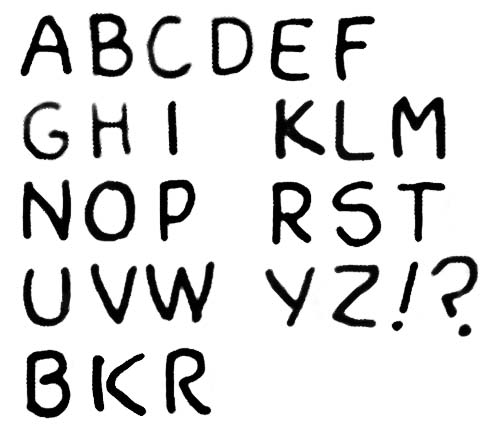

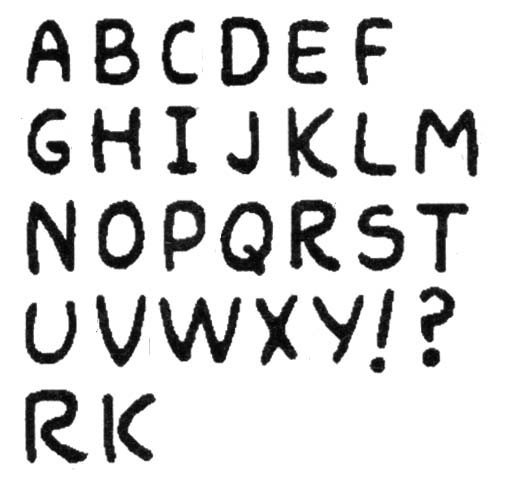

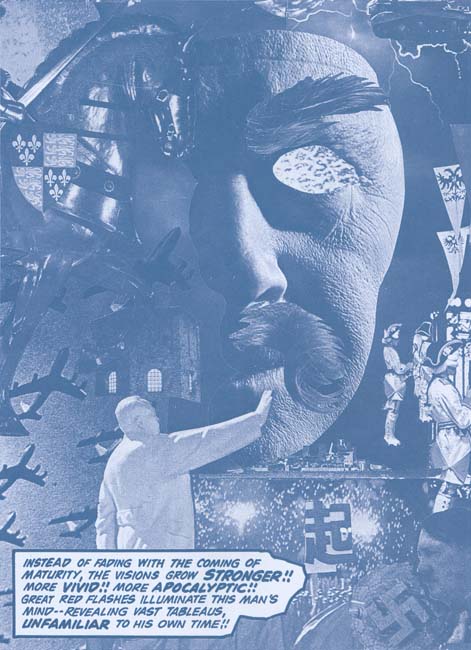

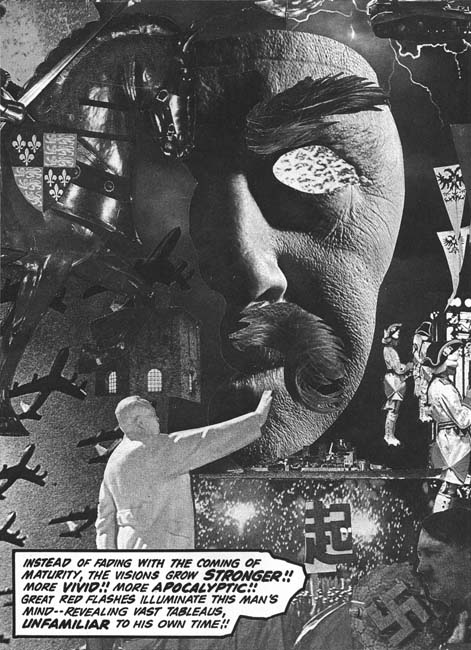

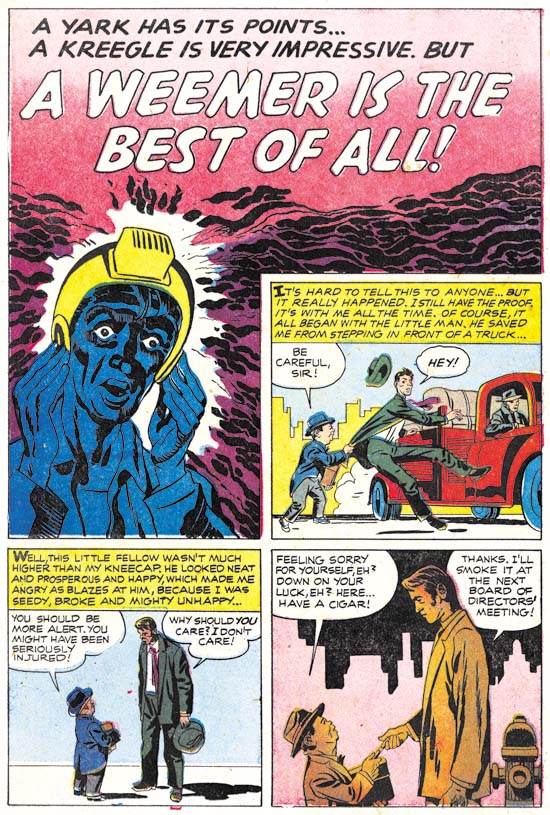

The Simon and Kirby studio employed a number of artists whose identity has not been determined. So it might seem odd to spend much time writing about just on of them. I have written before about the artist that I will discuss here but he has such a puzzling combination of traits that I want to collect in one place what little I known. (previously in Art of Romance, Chapter 4 and Chapter 8, and What? Who?)

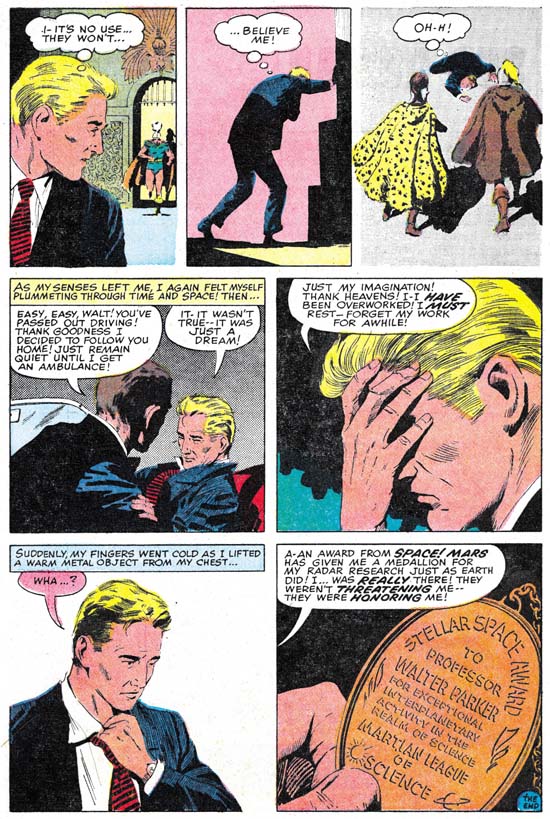

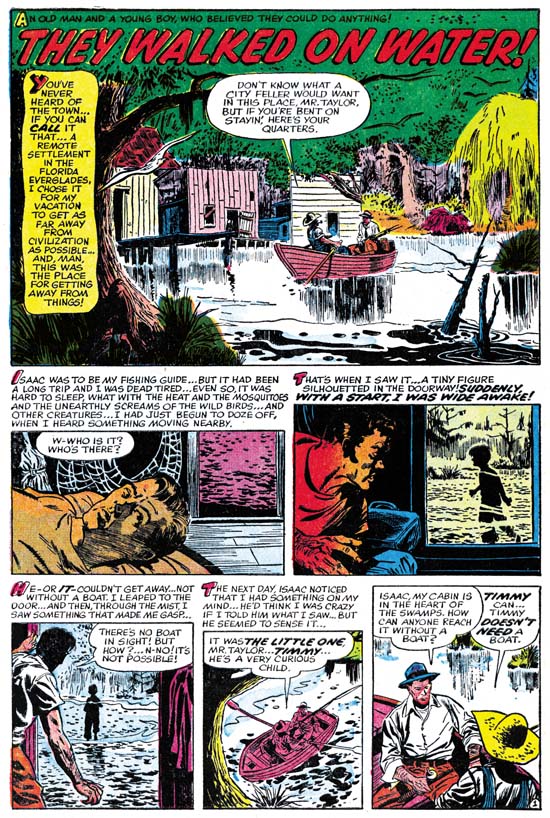

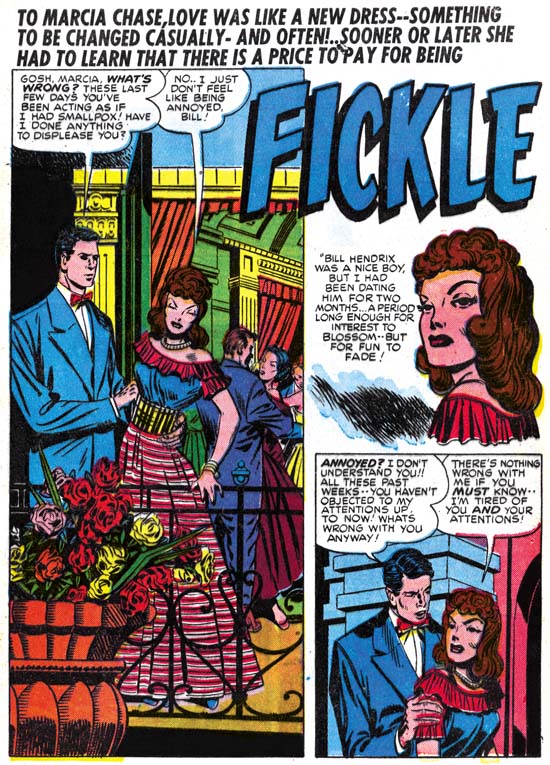

Young Love #1 (February 1949) “Fickle”, pencils by Jack Kirby and inking by an unidentified artist

The earliest piece of work that I believe this artist had a hand in appears in “Fickle” from Young Love #1 (February 1949). The man in the splash panel and second story panel is long and lanky with a small head. This is perhaps the most distinguishing feature of this unidentified artist. Although somewhat stylized, the woman in the first story panel looks very much like she was drawn by Jack Kirby. In fact the entire story consistently looks like Kirby’s work although tall lanky figures appear in different places. There is little doubt that Kirby did the pencils and the unidentified artists was in this case an inker. The quality of the inking in the story is quite variable and so I suspect more than on artist had a hand in the inking. This was after all the unusual practice in the Simon and Kirby studio, at least when it came to work drawn by Jack. For the most part the inking was done in what I describe as studio style inking with such techniques as picket fence crosshatching and abstract arc shadows (Inking Glossary). It does seem that some of the parts that show the tall lanky figures display much less of these techniques.

Many months will pass before the next piece that I attribute to the unidentified artist. That is not to say that he did no more work. Having contributed to the inking of one Kirby piece I suspect he may have help ink others as well. That other inking work just has not yet been identified.

Real West Romances #4 (October 1949) “The Perfect Cowboy”, pencils by Jack Kirby and inking by an unidentified artist

The tall and lanky figure appears once again in “The Perfect Cowboy” from Real West Romances #4 (October 1949). That style is best shown in the splash page but I have chosen a page that portrays a number of this artist’s style. Even so the lanky figure can be seen in panels 1 and 3. The story is inked in the studio style but it exhibits some rather unusual twists to that style. The artist uses picket fence crosshatching in the woman’s hair as can be seen in the last two panels of the page. This gives the hair a rather unusual look and is something I have never seen another artist do. Actually this seems to have been a bit of an experiment by this artist and is one that he did not repeat. Another unusual inking technique is the use of simple crosshatching in the some of the dust clouds such as seen in the third panel. I have never seen another Simon and Kirby artist do that but if this also was an experimental inking technique it was one that the inker was happy with and would use again.

Many of the faces seem somewhat simplified particularly in the way the eyebrows are depicted which is rather like Meskin’s approach. The woman’s eyes often seem to be at a bit of an angle with one another in a manner similar to that used by Marvin Stein. I hasten to add that neither Meskin nor Stein drew lanky figures or used simple crosshatching in dust clouds. While some of the faces may look a little like the work of Meskin or Stein, others look very much like the work of Kirby. In fact the entire story is laid out in manner so typical of Kirby that I have little doubt that Kirby did the pencils for this story and our unidentified artist did the inking. Unlike “Fickle” the inking is consistent throughout the story and I am confident that it was largely the inking by one hand. Frankly I suspect the original pencils were rather nice but the inker’s heavy hand has pretty much overwhelmed Kirby’s pencils.

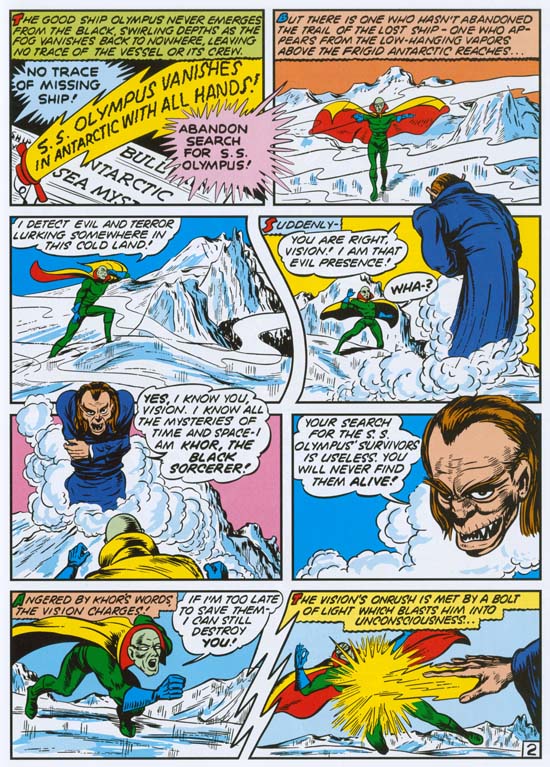

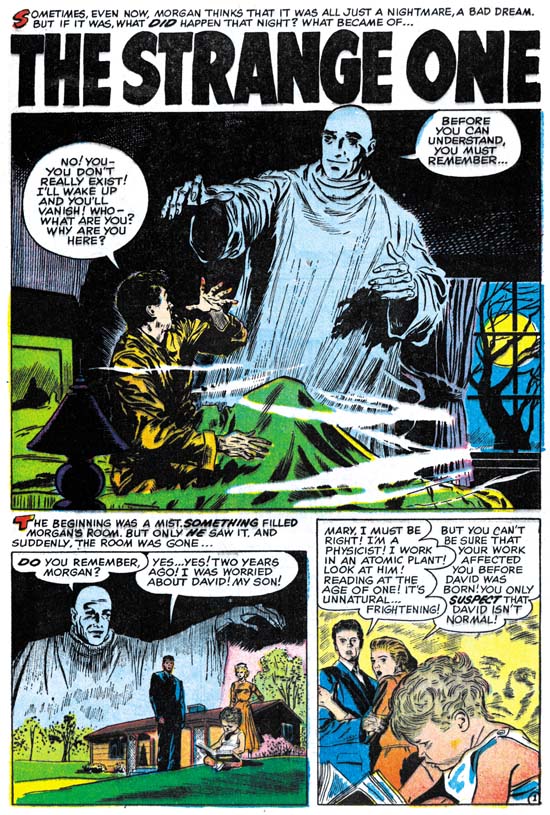

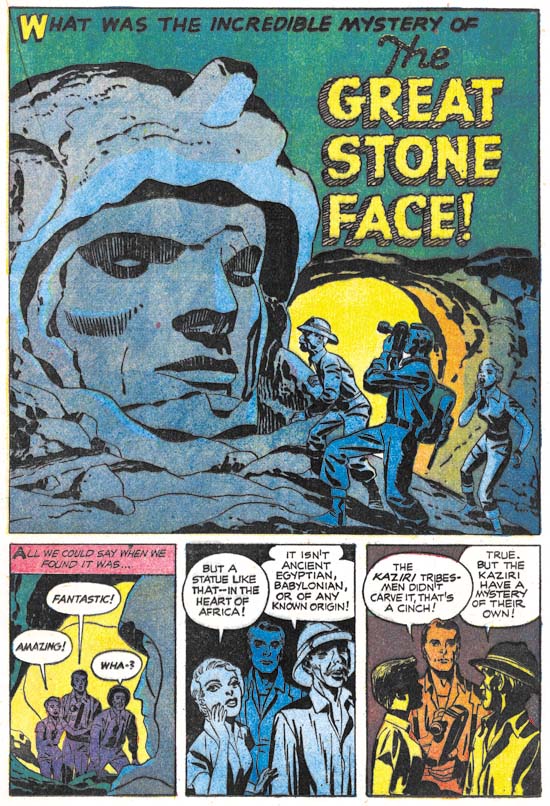

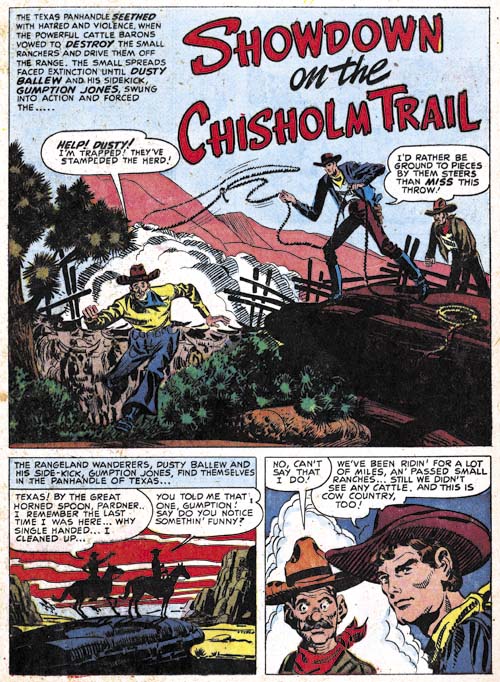

Prize Comics Western #78 (November 1949) “Showdown on the Chisholm Trail” pencils and inks by an unidentified artist

This artist next appears in “Showdown on the Chisholm Trail” from Prize Comics Western #78 (November 1949). The splash provides an excellent example of this artist trademark tall and lanky figures. There are certain panels in the story that seem to look a little like Kirby’s work and others that suggest Mort Meskin. However the great majority of the art seems distinct from either Kirby or Meskin so I feel pretty certain that these are this artists own pencils. Those parts similar to Kirby or Meskin are probably due to swiping.

For the most part this story is inked in the studio style. While the inking has its own unique traits it does resemble Meskin’s inking when that artist inked Kirby pencils. The unidentified artist inked eyebrows very much like Meskin and this may be one of the reason that the art has such a Meskin look to it. Once again we find simple crosshatching applied to dust clouds such as seen in the splash panel above. I have not found any other artist in the Simon and Kirby studio who did this.

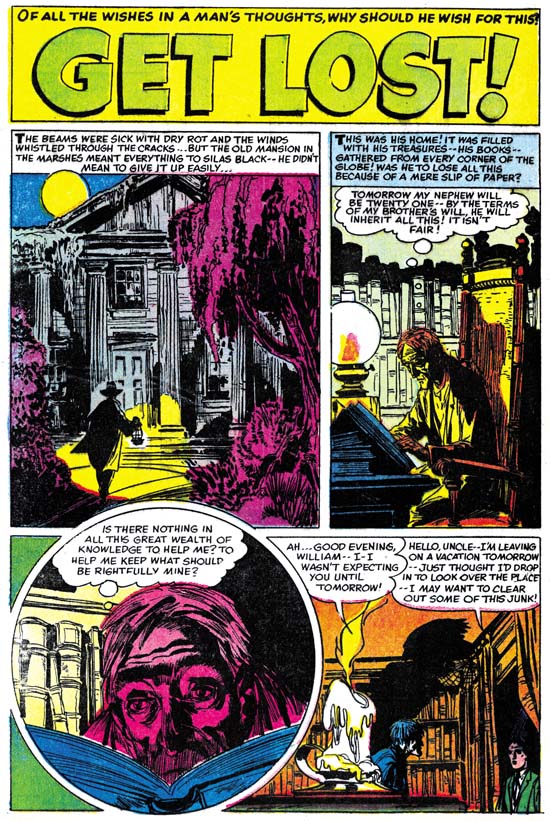

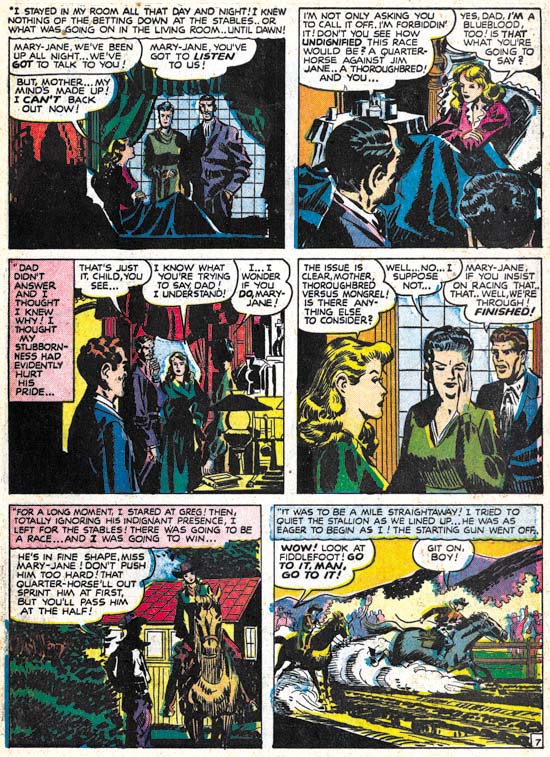

Western Love #3 (November 1949) “The Blue Blood and the Bum” page 7, pencils and inks by an unidentified artist

Another story by this artist, “The Blue Blood and the Bum”, was published in the same month. It appeared in Western Love a title that combined the romance and western genre. As such it makes for easy comparison to “Showdown on the Chisholm Trail”. Some of the same traits appear such as tall and lanky figures, simple cross hatching in dust clouds and simple Meskin-like eyebrows. There does appears that the inking has less of an emphasis on the studio style. The story on a whole seems to mimic less the style of Kirby or Meskin.

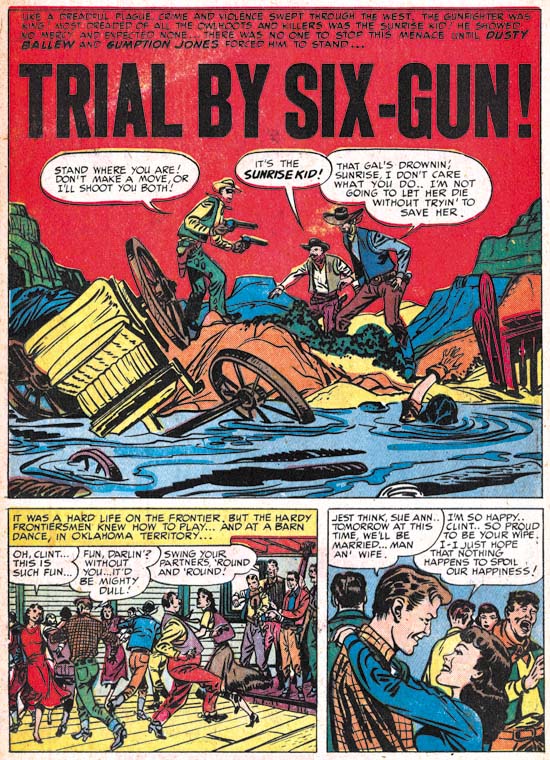

Prize Comics Western #80 (January 1950) “Trial by Six-Gun”, art by two unidentified artists

The final example that I have found for this mystery artist is found in “Trial by Six-Gun” from Prize Comics Western #80 (January 1950). The tall and lanky figures found in the splash panel seem a perfect match for the work of this unidentified artist. However the rest of the story, including the two panels below the splash, look very different from this artist’s work. Two months seem much too short a time to effect such a transformation and so I am sure this is the work of another artist. How such a combination came about will probably remain one of those minor mysteries.

These five stories are all that I could find by this artists despite much searching. I will admit that it is quite possible that he did some inking of Kirby pencils that I did not spot. I guess my main interest in this artist was to come to understand exactly what was his contribution to “The Perfect Cowboy”. A comparison of that story to the others has convinced me that “The Perfect Cowboy” was penciled by Jack Kirby and owes its unusual look to the overwhelming effects of the unidentified artist’s inking.