(Headline #26 – #28, Justice Traps the Guilty #1 – #1)

September 1947 (cover date) was the release of Simon and Kirby’s Young Romance. This marked a milestone for the creative duo. Previously Joe and Jack had not signed any of the work that they provided for publishers Prize or Hillman with the exception of Hillman’s My Date. Starting in September Simon and Kirby signatures would appear not only in Young Romance but in Headline Comics as well. Jack Kirby drew four stories of Headline #26 and three of those were signed. From this point on Simon and Kirby signatures would frequently be found on Kirby’s drawings for Prize Comics. Despite all the work that S&K provided to Hillman, in the end it was Prize that got Joe and Jack’s commitment. Right from the start the crime version of Headline was produced by Simon and Kirby while they never seem to have the same influence with Hillman. Surely whatever deal that Joe and Jack made with Prize must have reflected their greater control over Headline while at Hillman they had remained only marginally better then just work for hire. In the end Simon and Kirby were businessmen and it was all about the money. By early next year Simon and Kirby’s work for Hillman would end.

The crime version of Headline Comics must have been a very successful seller. After just the first four bimonthly issues Prize introduced a new crime title Justice Traps the Guilty. Simon and Kirby produced JTTG as well and there really was no difference in the contents between Headline and JTTG. Since both were bimonthly titles, effectively there would be a crime comic released by Prize each month. There must have been some difficulty because JTTG #2 should have been scheduled for December but was released in January instead; while Headline #28’s normal January release was pushed back to February.

Jack Kirby would still be the main contributor to Headline Comics and the new Justice Traps The Guilty. Jack drew 4 out of 6 stories for Headline #26 (September), but would only draw two stories each for issues #27 (November) and #28 (February). The first issue of Justice Traps the Guilty followed the Simon & Kirby’s modus operandi of starting a title with lots of Kirby; Jack penciled 6 out of the 8 stories. However with the second issue Jack returns to supplying a more modest 2 stories. Still no other artist appeared more often then Jack in these issues.

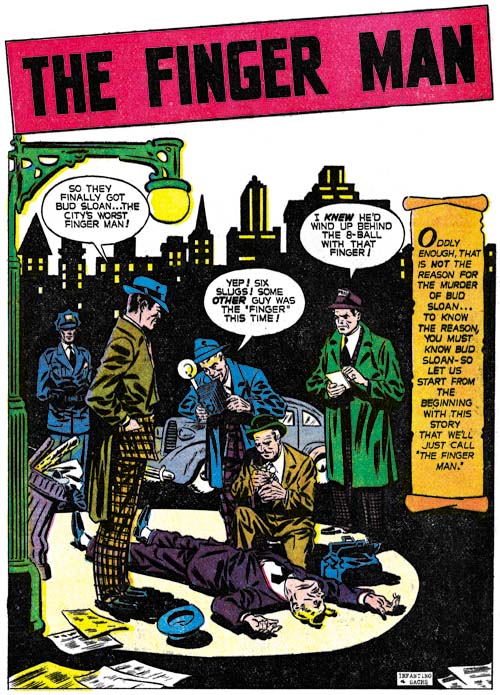

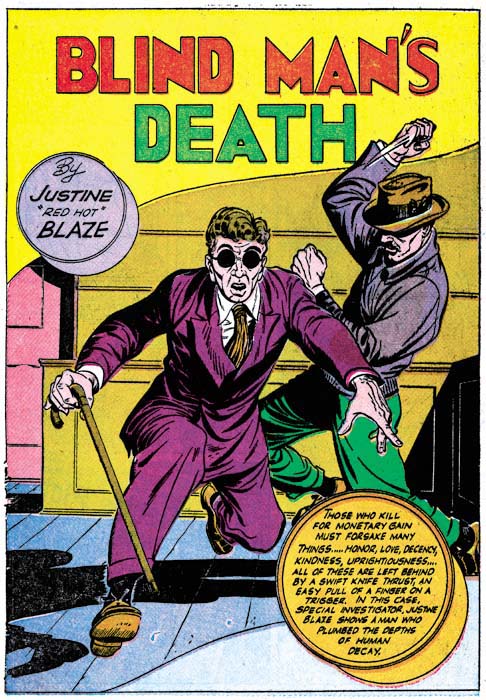

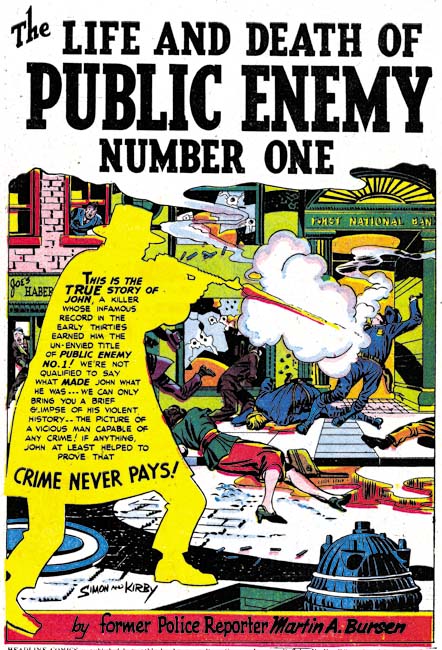

Headline #26 (September 1947) “The Life and Death of Public Enemy Number One”, art by Jack Kirby

The splash for “The Life and Death of Public Enemy Number One” uses a silhouette. There seemed to have been a flurry of the use of this device because we have seen it previously. However it would be pretty much dropped by Simon and Kirby and this may be its last use. While making the overall design of the splash more interesting, the use of silhouette diminished the impact as well.

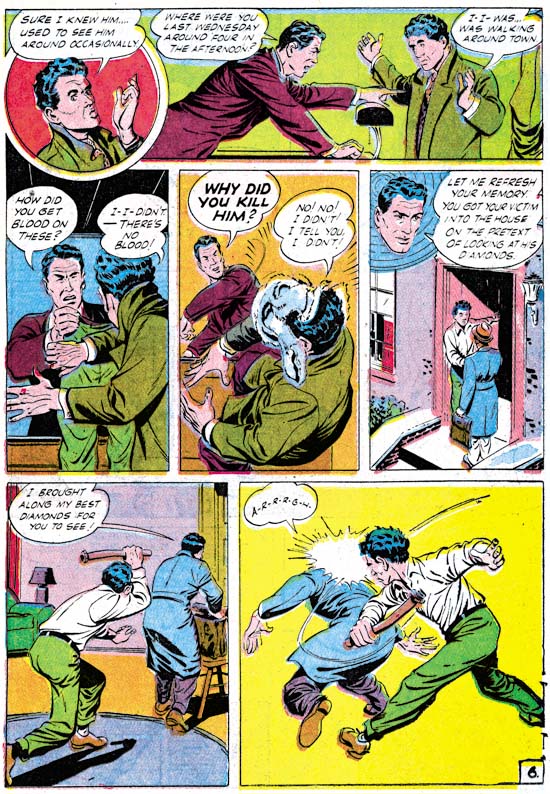

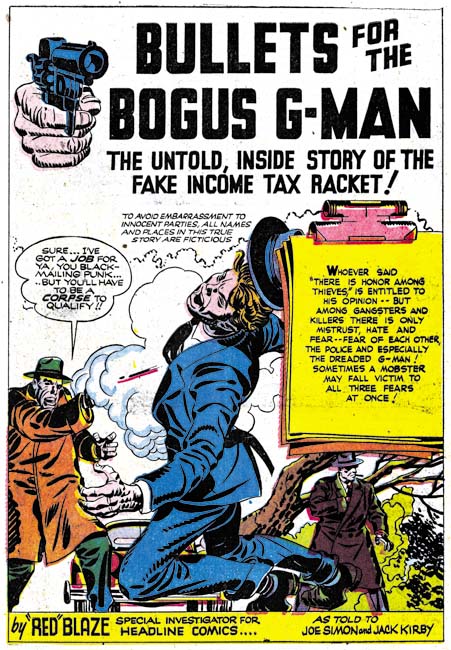

Headline #26 (September 1947) “Bullets for The Bogus G-Man”, art by Jack Kirby

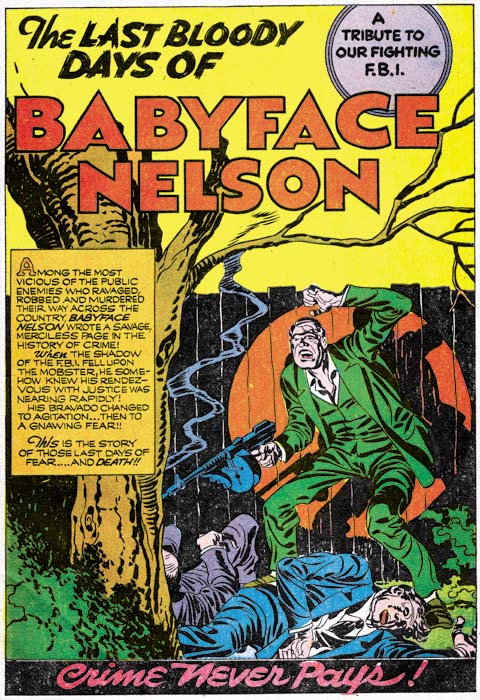

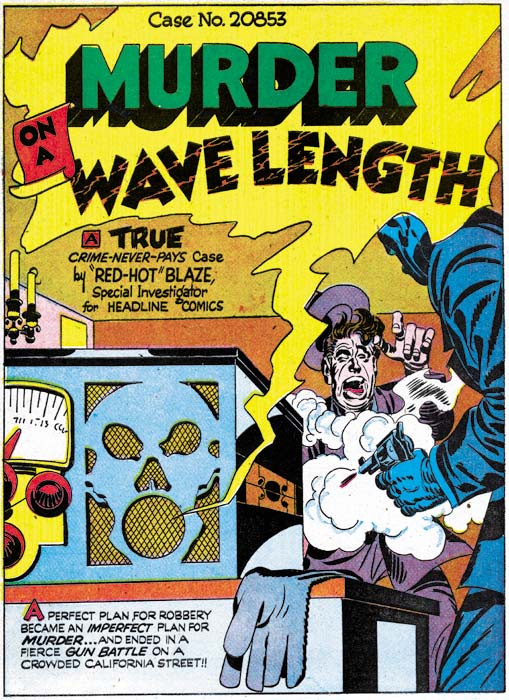

Another device used by Simon and Kirby in the early Prize crime comics was having “Red” (or “Red-Hot”) Blaze introduce the stories. While I suspect that Simon and Kirby found it a useful idea when they were promoting the idea of crime comics to Prize and for the initial in-house advertisements, in the end it just took up story panels that would had been better served for telling the actual story. “Bullets for the Bogus G-Man” may have been the last use of “Red” Blaze and even there he is only mentioned in the caption at the bottom of the splash page and never makes an actual appearance in the story.

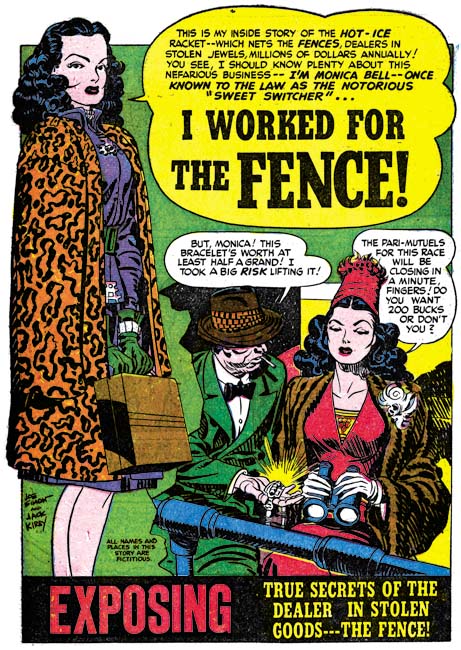

Headline #28 (February 1948) “I Worked For the Fence”, art by Jack Kirby

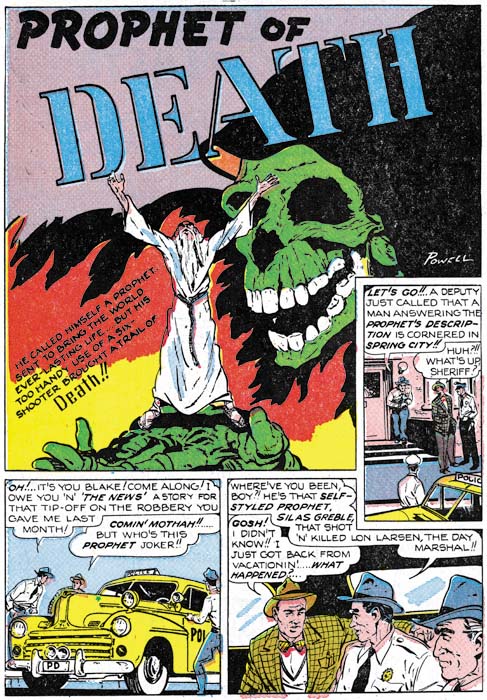

One motif Simon and Kirby sometimes used for the first story was adopted from previous use in Young Romance. That is having a character introducing the story and using the word balloon as the title caption. Simon and Kirby did not use this design technique as frequently in the crime titles as they would in Young Romance but it still was an effective part of their repertoire.

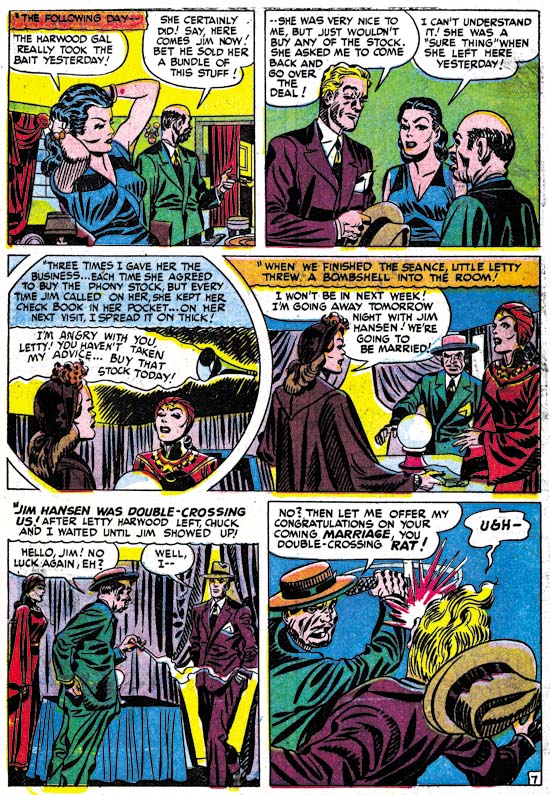

Headline #27 (November 1947) “Spirit Swindlers” page 7, art by Jack Kirby

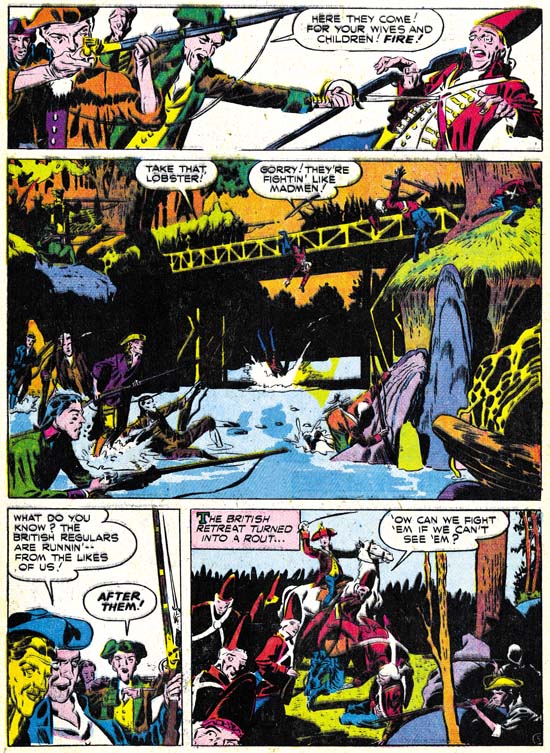

I have remarked before that circular panels was largely limited to an occasional splash page for the work that Simon and Kirby did for Hillman. For the Prize issues discussed in this chapter, Joe and Jack continued to use circular panels. What was new is that while previously almost all the Prize comic stories used circular panels in Headline #26 to #28 and JTTG #1 and #2 about half of the stories did not use round panels at all. For the stories that still featured circular panels they are used in lower proportions. For Headline #23 to #25 ratios of rounded panels to all the panels was over 16% and in one story reached 20%. Remember for a story done in the standard 6 panels per page, this would work out to an average of a semi-circular panel for each page (although they rarely were distributed so evenly). For Headline #26 to #28 and JTTG #1 and #2, when rounded panels were used they were generally used in the range of 14% to 10%. This is only a small decrease, but it seems to be consistent. In one story (“The True Life Story of Alvin Karpis” it drops to 4%. The last issue covered in this chapter (Headline #28, February 1948) did not have any rounded panels.

I have also been trying to track the evolution of the inking techniques used. Previously in Headline drop strings and abstract arch shadows, typical Studio style mannerisms, had become commonly used. Picket fence crosshatching and shoulder blots were still rare and when found are not typical in execution. (See my Inking Glossary for explanations of the terms I use to describe these techniques). In the last chapter we saw those final typical Studio style techniques show up suddenly in the Hillman crime title. The same thing happened at Prize. The earliest typical picket fence brush work for Prize that I have noticed was in “Spirit Swindlers” (see above image, particularly panels 4 and 6. There seems to be no gradual conversion of previous simple crosshatching to picket fence crosshatching; picket fence just suddenly appears. The picket fence inking shows up elsewhere in the story as well. Not every story in the same issue, however, shows the use of this most distinctive inking. Also note the shoulder blot in panels 1 and 2.

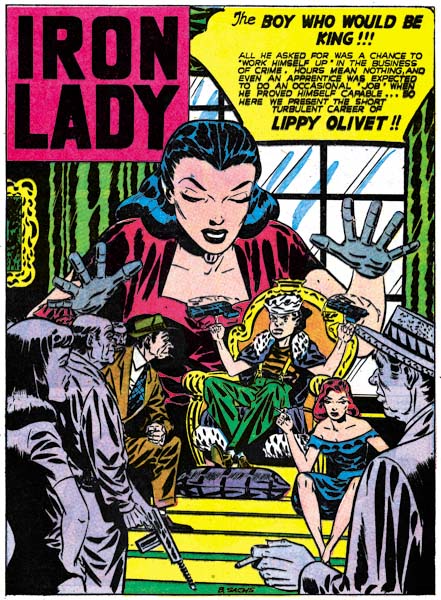

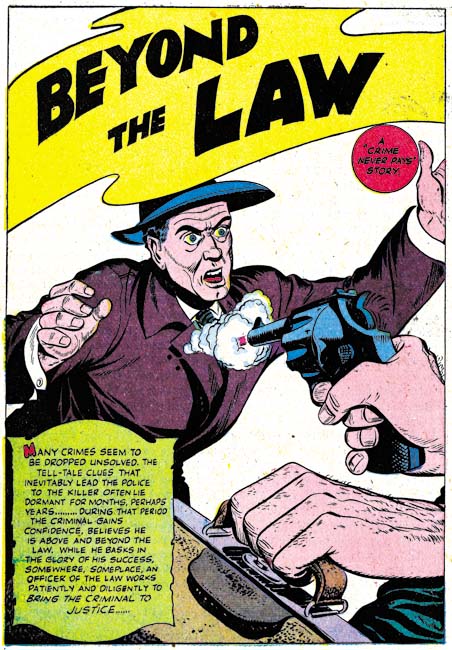

Headline #26 (September 1947) “Beyond the Law”, by unidentified artist

As mentioned above, Kirby drew 4 of the 6 stories for Headline #26. The other two stories (“Test of Death” and “Beyond the Law”) were done by the same artist. I have not been able to identify him but he also did “Murder’s Reward” and “Blind Man’s Death” from Headline #25. Ger Apeldoorn has suggested that it might be Bob McCarty. I am most familiar with McCarty’s work for S&K’s Mainline titles. The Mainline material does not resemble these four stories but that could be explained by the seven years separating the two groups of work. In any case the work in Headline #25 and #26 was done by a talented artist who played an important part in the early Headline issues. After issue #26 the artist stopped providing work to Simon and Kirby.

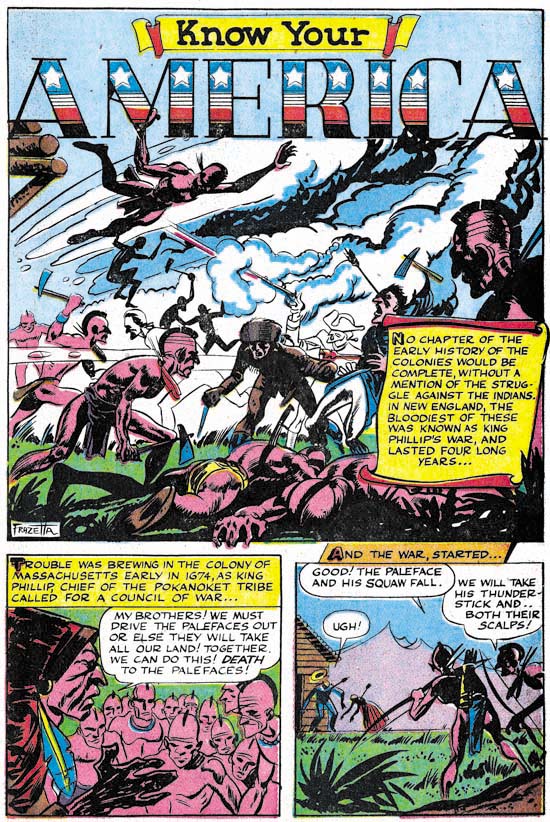

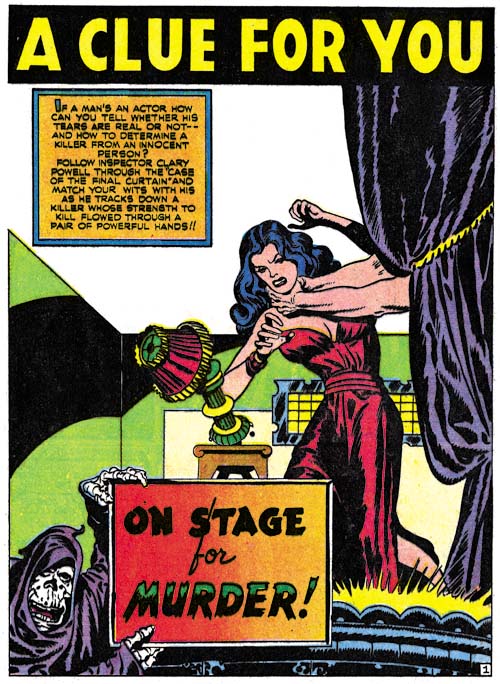

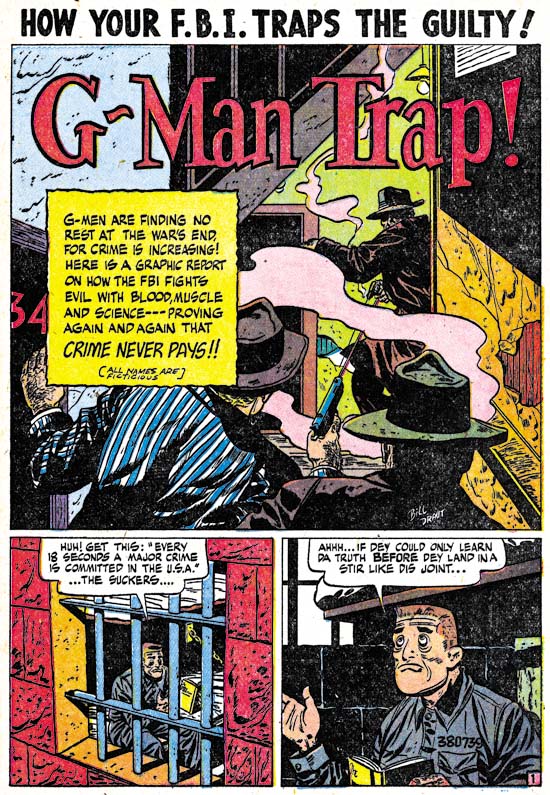

Justice Traps the Guilty #1 (October 1947) “G-Man Trap”, art by Bill Draut

After the mystery artist last appearance in Headline #26, his place as the most important supporting artist (after Kirby) was taken by Bill Draut. Draut’s first returned to the Simon and Kirby productions in Young Romance #1 (September 1947). From that point on Bill would be a mainstay of the S&K studio until its breakup. Draut would provide two stories each issue for Headline #27 and #28 as well as JTTG #1. In those issues Draut’s contributions of stories equal that of Jack Kirby. It is interesting to see Draut’s take on crime since so much of his output for the Simon and Kirby studio was for romance titles. Bill could be surprisingly effective with action and he also did some interesting splashes. The one for “G-Man Trap” is a good example. The use of diagonal elements makes the splash visually stimulating. However, the placement of the gun smoke and the odd pose of the shooter in the background really did not work well and diminishes what should have been an interesting confrontation. Still you have to admire Draut for the attempt made even if it was not completely successful.

Justice Traps the Guilty #1 (October 1947) “Try an FBI Test” page 2, art by Bill Draut

As I have mentioned a number of times in the past, I am convinced that Kirby did not supply layouts for Draut as some experts have suggested. Bill’s means of telling a story and his splash designs (such as the one from “G-Man Trap” shown earlier) are often different from Jack’s. There is one story, “Try an FBI Test”, that might suggest otherwise. Note the use of circular panels. These appear throughout the story and are the same form that Kirby uses. While this might suggest that Kirby did the layouts, I am not convinced. In “Try an FBI Test” the captions and word balloons frequently extend beyond the border of the circular panels which is unlike Kirby’s use where both captions and work balloons invariable are confined within the circular boundary. Nor was there any real change in the way the story is graphically told compared to other work by Draut. I believe Draut has just trying a layout technique that he previously observed Kirby using. Whatever the reason for the use of circular panels, it was a one time occurrence as I do not believe Bill would ever used it again.

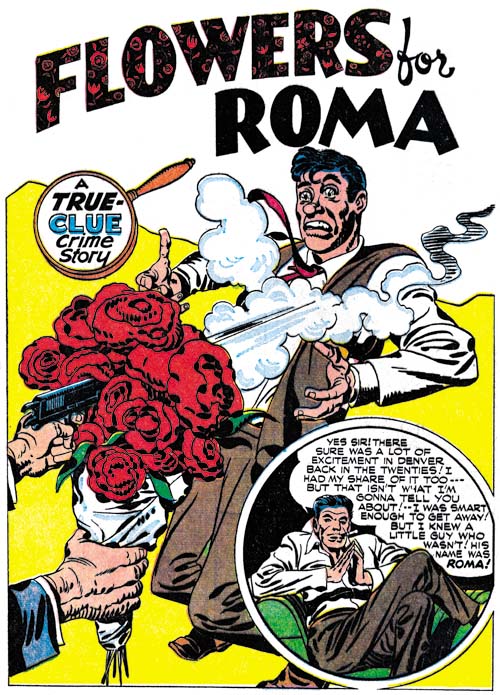

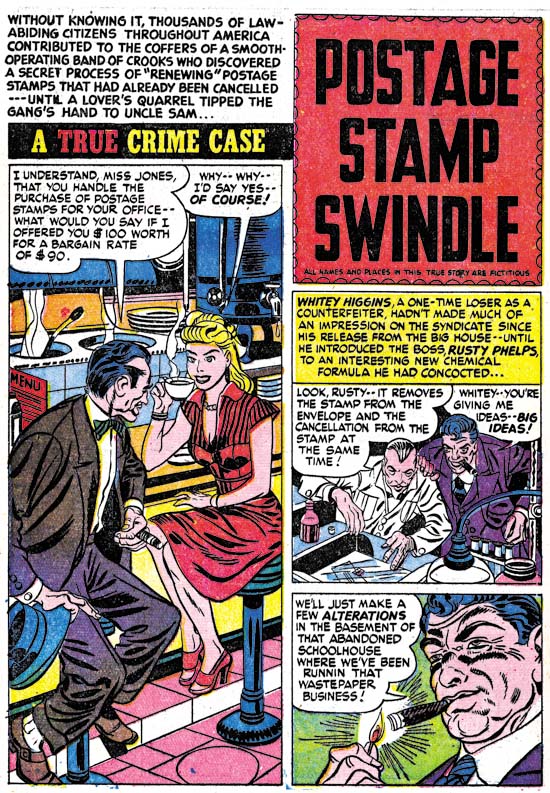

Headline #28 (February 1948) “Postage Stamp Swindle”, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

Young Romance #3 (January 1948) saw the first appearance of the Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin team working for the Simon and Kirby studio. “Postage Stamp Swindle” (Headline #28, February 1948) was the first crime work that they did for S&K. As a team, Robinson and Meskin would only work for Joe and Jack for about seven months and provide a total of ten pieces of work. Only two of the stories are signed but the unsigned work is very consistent with those bearing signatures. Jerry and Mort had a preference for splash pages with a vertically dominated splash panel with two story panels also vertically arranged. The first page of “Postage Stamp Swindle” exaggerates that motif by placing the title over the story panels in a caption shaped like a stamp. Otherwise the splash panel usually had the shape of an inverted ‘L’.

I have been assigning the pencils to Jerry and the inks to Mort. This was due to the order that their names appear in their signature. Further the inking does predominately look like Meskin’s. Recently I have been spending some time looking over some of Meskin’s work from 1946 and 1947. I find that the work Robinson and Meskin’s supplied for Simon and Kirby look very much like the early work that Mort did on his own. So much so that I wonder what Robinson’s contribution was? I am tempted to attribute all the early unsigned art for S&K as Meskin alone and only credit the last three stories, two of which are signed, to the Robinson and Meskin team. I have two reasons for not taking that course. One is the still great similarity of the signed and unsigned work. The second is Joe Simon’s story of when Mort came to work for the Simon and Kirby studio as described in his book “The Comic Book Makers”. Joe really makes it sound like that was the first time Mort had worked for them which would not be true if Meskin was solely responsible for the work from 1948.

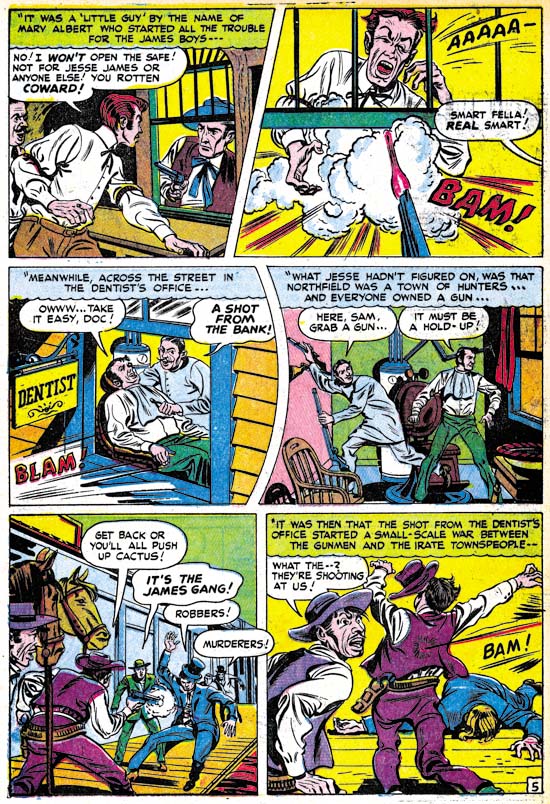

Headline #27 (November 1947) “The Guns of Jesse James” page 5, art by Jack Kirby and an unidentified artist

“The Guns of Jesse James” is one of those stories that at a glance were obviously done by some artist other than Jack Kirby; the drawing is just too crude. There are some places where the art, although still crude, looks like Jack’s style. The second panel in the page above is a good example. This story even uses rounded panels like those that Jack would use for some of his own stories. While it is possible that the artist was trying to mimic Kirby’s techniques, I think it more likely that he is working from rough layouts provided by Jack.

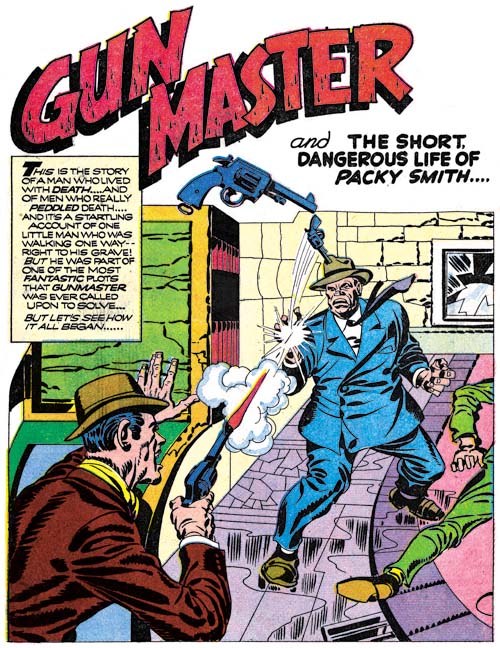

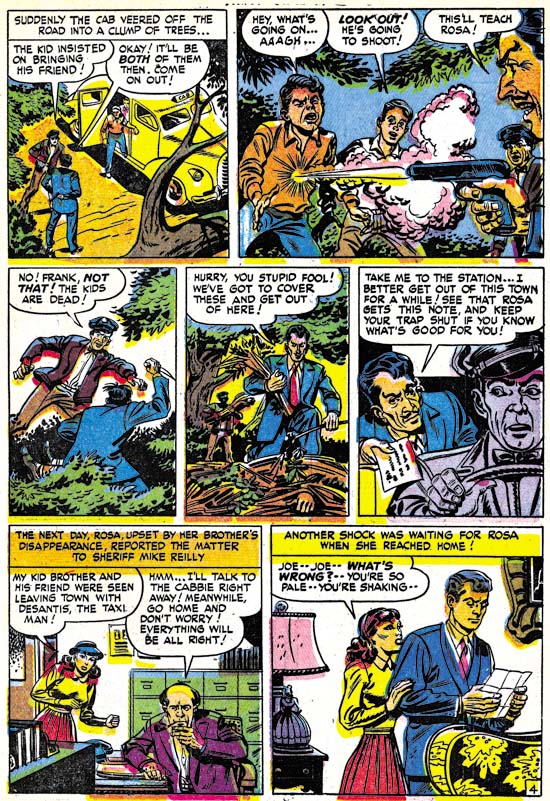

Justice Traps the Guilty #2 (January 1948) “The Killer Thought He Was Satan” page 4, art by an unidentified artist (Jack Kirby layouts?)

The possibility of rough Kirby layouts may also apply to “The Killer Thought He Was Satan”. Note in particular the second panel from page 4 shown above. In many ways the graphic story telling is even more like typical Kirby mannerisms then “The Guns of Jesse James”. Both of these stories come from a period where Kirby’s contributions had diminished and the use of layouts may have been an effort to filling the titles without using too much of Jack’s time.

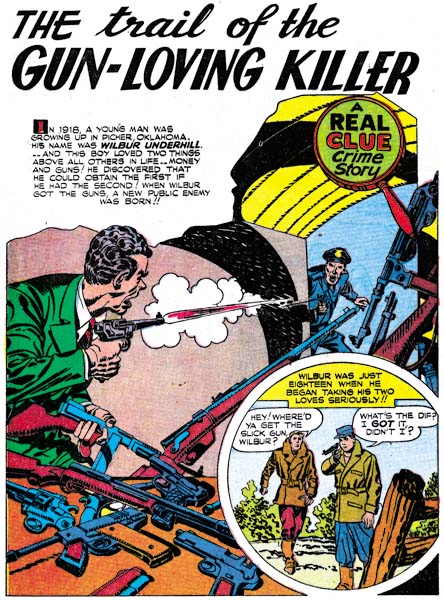

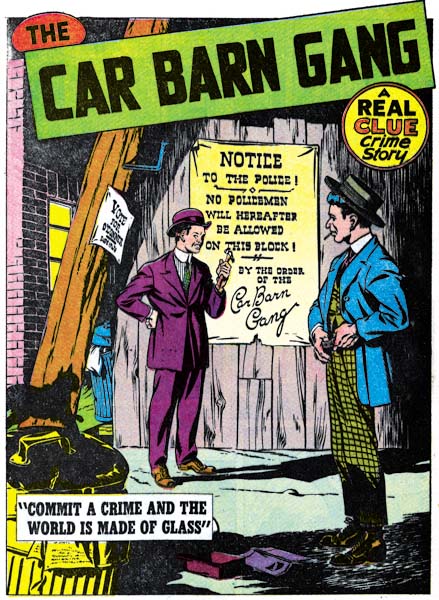

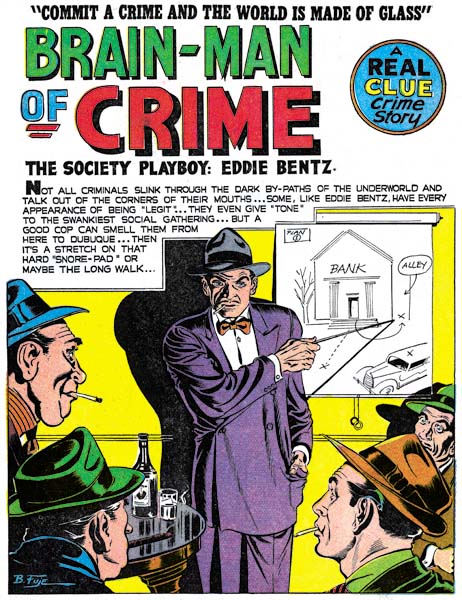

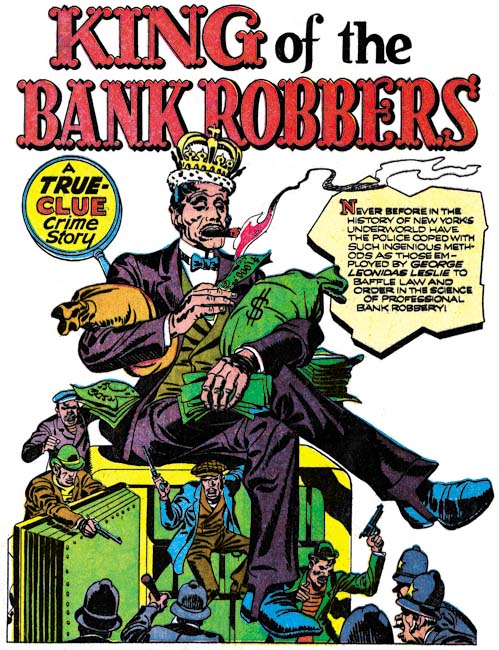

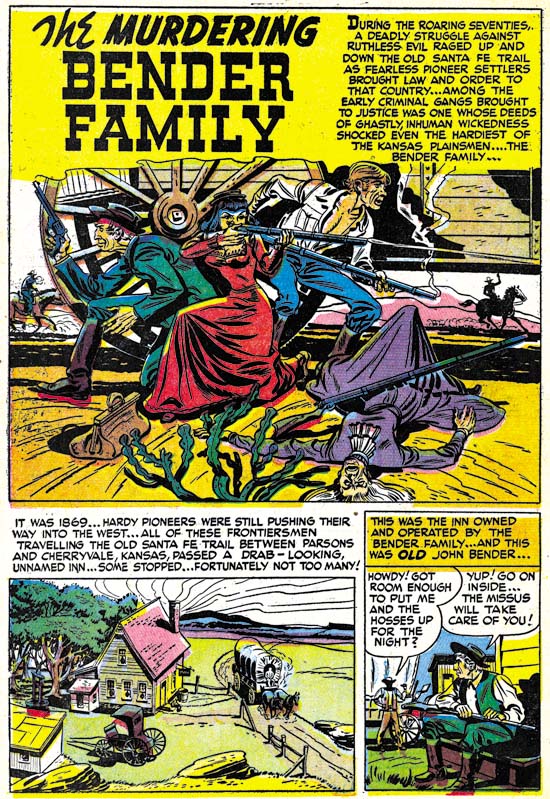

Justice Traps the Guilty #2 (January 1948) “The Murdering Bender Family”, art by an unidentified artist

As I precede in future chapters of this serial post I will certainly not try to cover every unidentified artist in these titles. While I would consider most, if not all, talented some were more deserving of recognition than others. Besides there will be too many artists that I have not identified yet. In these early issues of the crime titles, however, the number of artists appearing is much more limited. So I will close with the splash page of one of mystery artists. I sure wished more of them took advantage of Simon and Kirby’s willingness to allow artists to include their signatures.

Chapter 1, Promoting Crime

Chapter 2, A Revitalized Title

Chapter 3, Competing Against Themselves

Chapter 4, Crime Gets Real

Chapter 6, Forgotten Artists

Chapter 7, A Studio With Many Artists

Chapter 8, The Chinese Detective

Chapter 9, Not The Same

Chapter 10, The Master and His Protege

Chapter 11, The New Team