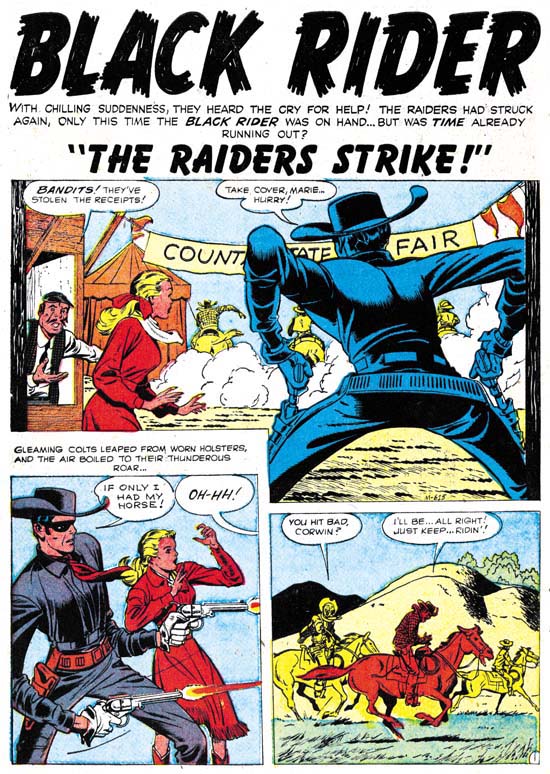

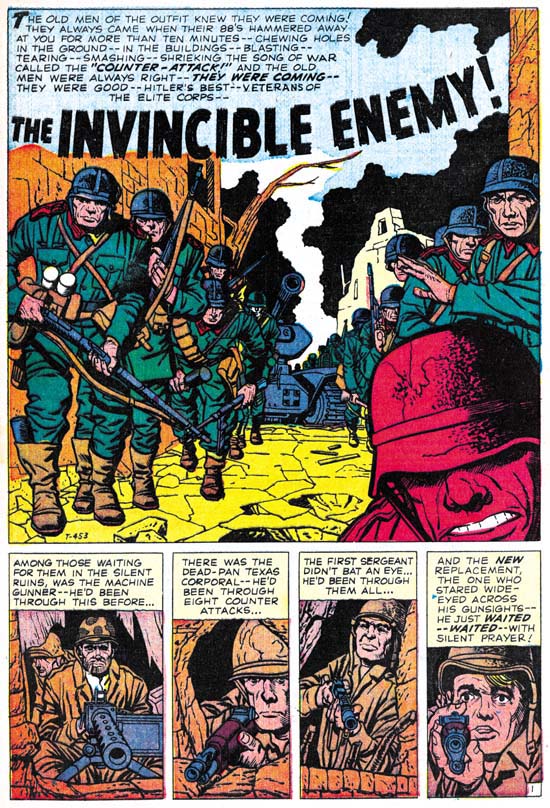

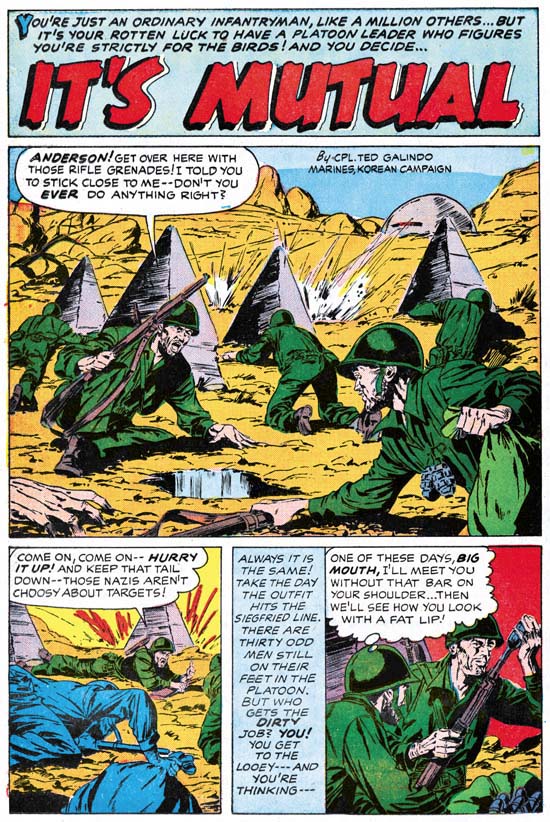

Black Rider Rides Again #1 (September 1957) “The Legend of the Black Rider” page 1 art by Jack Kirby

The Black Rider was a western costume hero along the lines of the Lone Ranger. Apparently his first appearance was All Winners Western #2 (Winter 1948). Black Rider Rides Again #1 reintroduces the hero after a lengthy hiatus. Therefore the first story provides information about his origin. We learn that as a very young man our hero’s family was killed by an outlaw. When he was older he tracked down the outlaw and killed him in a gunfight. At his trial he threw himself on the mercy of the court, which gave him probation. The judge then helped him to become a doctor. Doc started his profession during a dispute between some ranchers and rustlers. Doc refuses to help, saying he is not a fighting man. In the end he finds he cannot ignore what is happening, so he puts on a black suit and a mask and saves the day.

The origin story told in the legend has many similarities to that of Bulls-eye, a Simon and Kirby creation. In both the hero’s family is massacred, the hero becomes phenomenal with a gun, maintains a secret identity that projects a unheroic personality, and adopts a mask when performing his heroic exploits. The first appearance of the Black Mask was in 1948, very much earlier then that of Bulls-eye in 1954. However the origin of Black Mask as described by Jess Nevins at A Guide to Marvel’s Pre-FF #1 Heroes sounds like it might be a little different. There is no mention of the death of Black Rider’s family. The circumstances involving the shootout that gets the young hero before a court are vague with no mention of a revenge killing. It sounds that the Black Rider may have been retconned slightly in this relauch attempt.

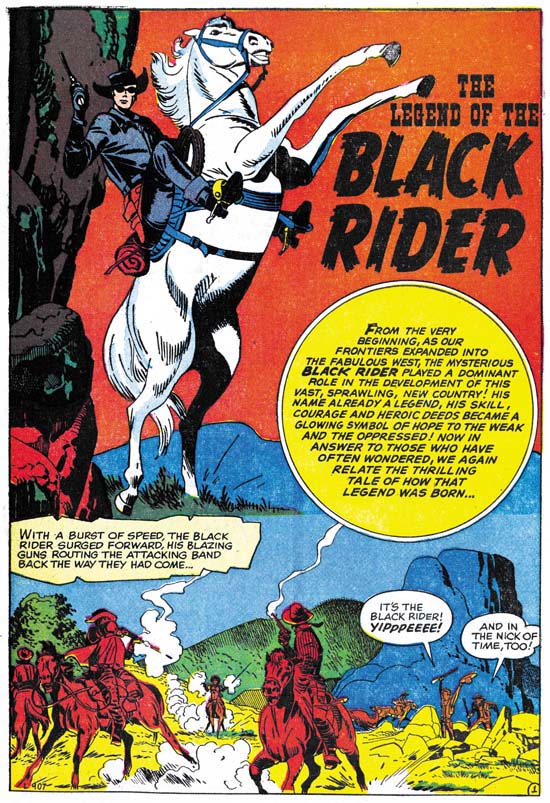

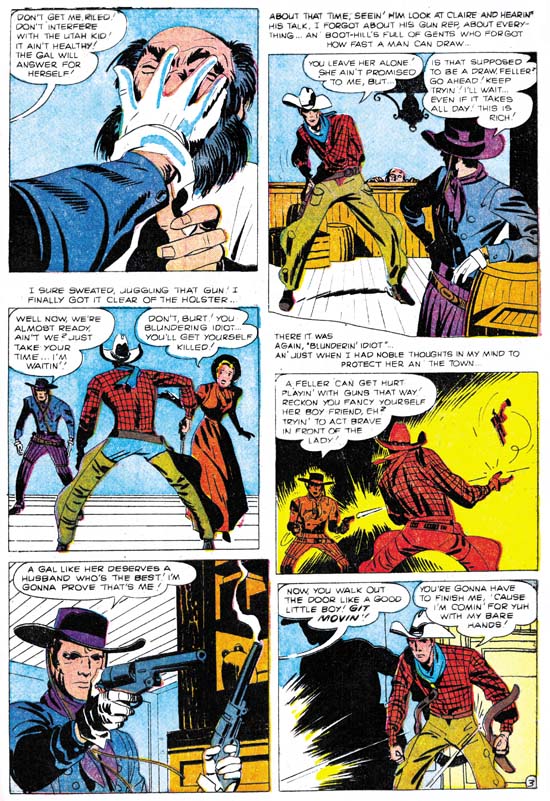

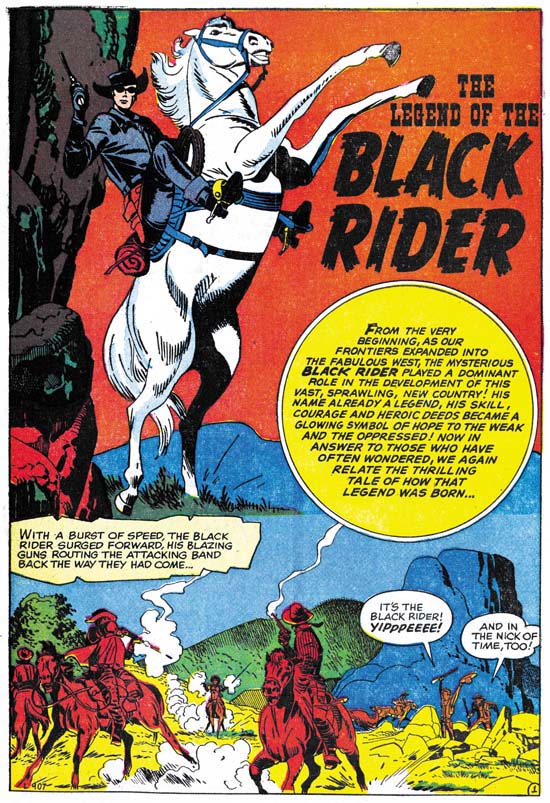

Black Rider Rides Again #1 (September 1957) “Duel At Dawn” page 1 art by Jack Kirby

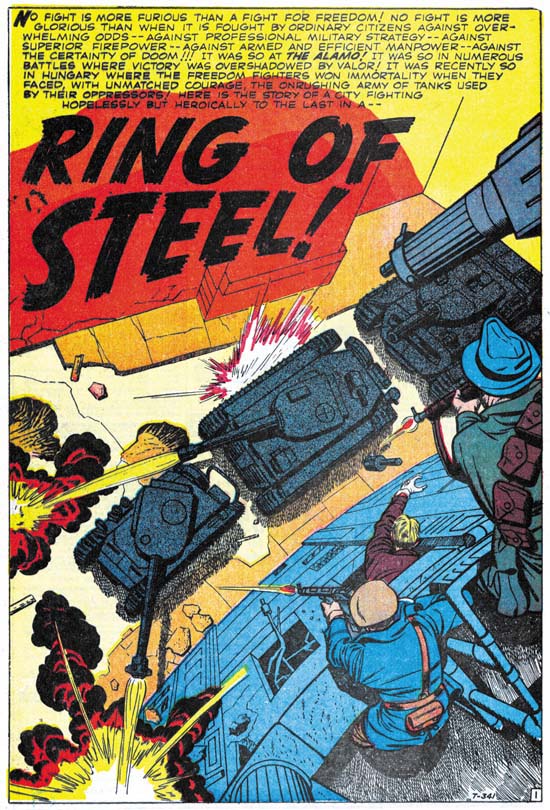

We enter the story as the Black Rider responds to an ambush attempt. He manages to wound the attacker but did not get a chance to identify him. Back home and back to being a doctor, a man comes in with a wound from a accident with barbed wire. Or so he says, the Doc recognizes it as a bullet wound. Later the Black Rider visits the man who under questioning admitted to having been offered money to ambush him. Before the man was able to say who offered the money, he is shoot. Once again our hero takes on the role as the Doc and saves the man’s life. Now the man will not say who is responsible. While recovering his assailant returns to finish the job, but of course the Black Rider saves the day.

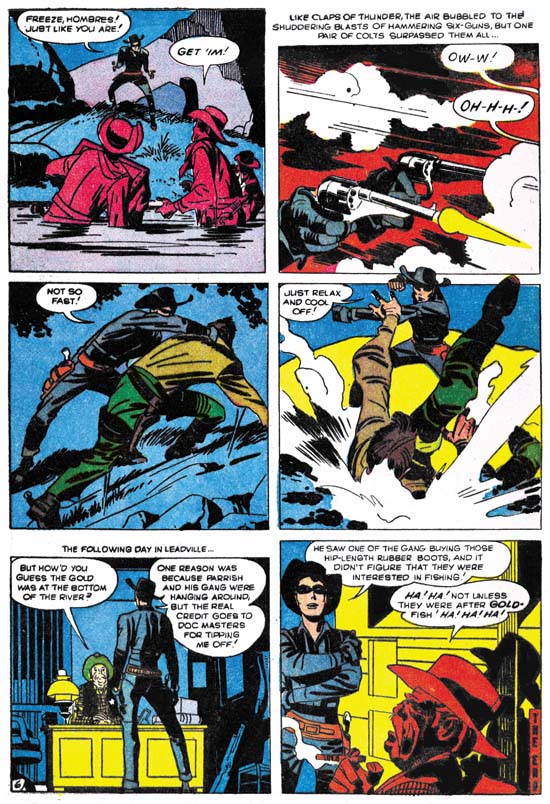

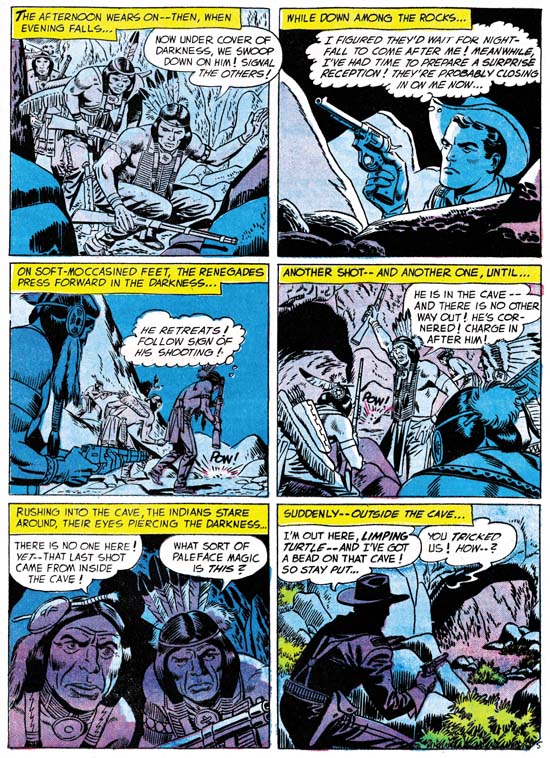

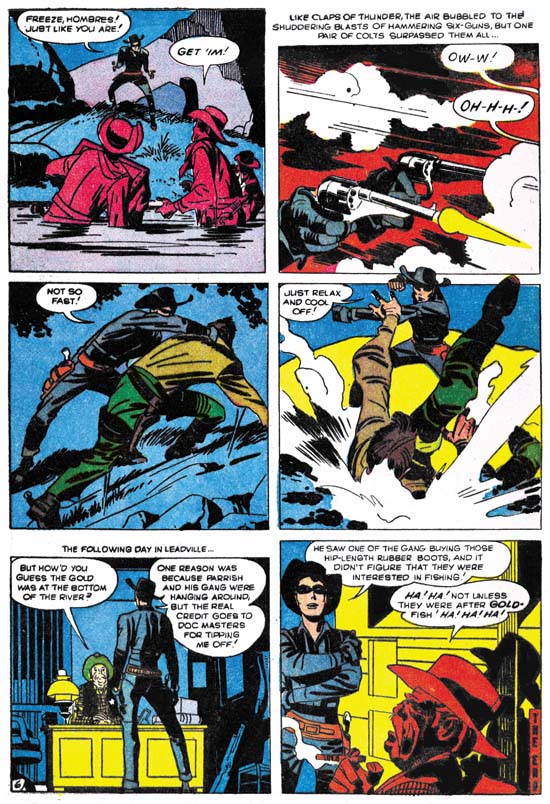

Black Rider Rides Again #1 (September 1957) “Treachery At Hangman’s Bridge” page 6 art by Jack Kirby

The midnight stage coach gets blown up but the Black Rider is nearby and arrives quickly. But not soon enough because he hears The thieves departing. Our hero changes his identity to become the Doc in order the help the wounded. The sheriff finds some men in the area but no sign of the stolen gold so he has to let them go. Doc keeps his eye on them and follows one who purchased supplies. Another change and the Black Rider surprises the thieves as the attempt to recover the stolen gold from the river.

These are not bad stories, but somehow I really cannot get that enthusiastic about them. The Black Rider is a little too successful. When he arrives he saves the day with no real effort. It is never quite clear why the Black Rider must hide his real identify. The rancher’s beautiful daughter’s interest in the Black Rider but not the Doc is a little too contrived. While Jack may have had something to do with retconned origin, on a whole I do not find many convincing Kirby-isms. If Jack was involve with the writing, his more personal touches were edited out.

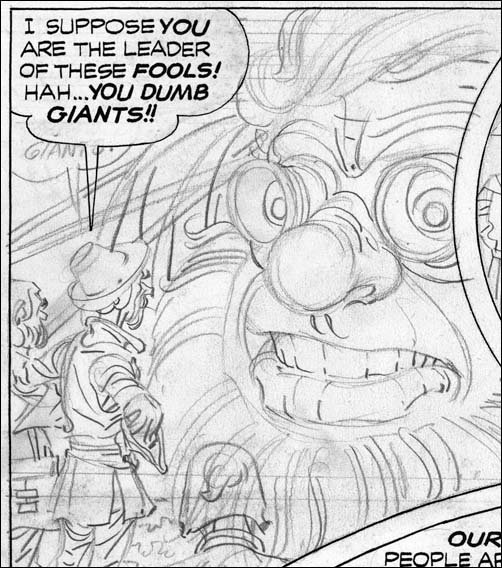

The art is rather nice with lots of fist fights, blazing guns, galloping horses, and exaggerated perspectives. Just the sort of things that you would expect from a Kirby western. Maybe it is mostly the inking, which I will discuss below, but this comic has more of a Simon and Kirby look then a Lee and Kirby one. Still no matter what your favorite Kirby period was, it is hard to imagine that you will not find something to appreciate in the art. There are also some interesting aspects to the panel layouts. Often figures extend beyond the panel edges. That sort of technique was more commonly used during the earlier days of Simon and Kirby most noticeably in the Captain America stories. But it was used much more sparingly if at all towards the end of the S&K collaboration. Another trait from Black Rider that was frequently used early on but abandoned later is the use of round panels. Interestingly circular panels also occur some of the initial Challengers of the Unknown stories done several months before.

Most of the inking is very much like what we found previously in “No Man Could Outdraw Him”. There generally is no crosshatching, spotting is more limited giving the art a light look, but when black is introduced it generally is produced by flooding an area with ink. In some ways it is very reminiscent of S&K shop style inking. In particular the way that black areas are used in the overall design. Conversely the lack of crosshatching is very unlike the S&K shop style of inking. As I said before I believe Jack developed this austere style of inking after the Simon and Kirby studio had disbanded. It allowed Jack to ink more quickly yet still provide a beautiful and effective job.

Although most of the inking appears to have been done by Jack himself, there are parts that look different. Some areas have been spotted using closely spaced lines, sometimes laid down using a straight edge other times by free hand. Generally the lines are roughly parallel, but occasionally there are some areas of true crosshatching. These lines appear to have been done using a pen, while most of the Kirby inking seems to have been done with a brush.

The splash page for “Duel At Dawn” (see above) provides some good examples of what I am talking about. Most of the inking is the severe style that I attribute to Kirby. But take a look at the mountain in the left part of the right story panel. The lines seem weak and the mountain seems mushy. Not only does it not look like Kirby’s work but the mountain itself seems to detract from the art. The line spotting of the mountains in the splash panel itself seem different and look more like Kirby’s hand. But most of the fine line inking in this book look like the panel version.

Black Rider Rides Again #1 (September 1957) “Duel At Dawn” page 5 panel 4 art by Jack Kirby

Above I give an example of the use of ruled lines for spotting. For me this use is less objectionable then things like in the hills because it does not change the overall design. But it still seems unnecessary. I believe that this fine pen inking not only was not by Jack, but it was not done under his direction either. I suspect that it was added after the art was delivered to Atlas.

In the past I have remarked that Jack seemed to have a good level of control of the work that he did for pre-Implosion Atlas. But that does not seem to be the case for Black Rider Rides Again #1. If Jack had been involved in the writing, it has been strongly edited. The pencil work is all Jack but the inking is not.

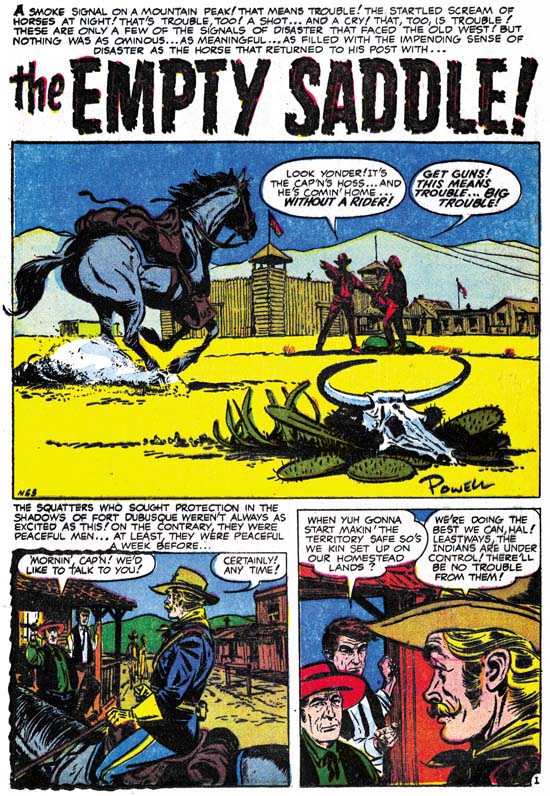

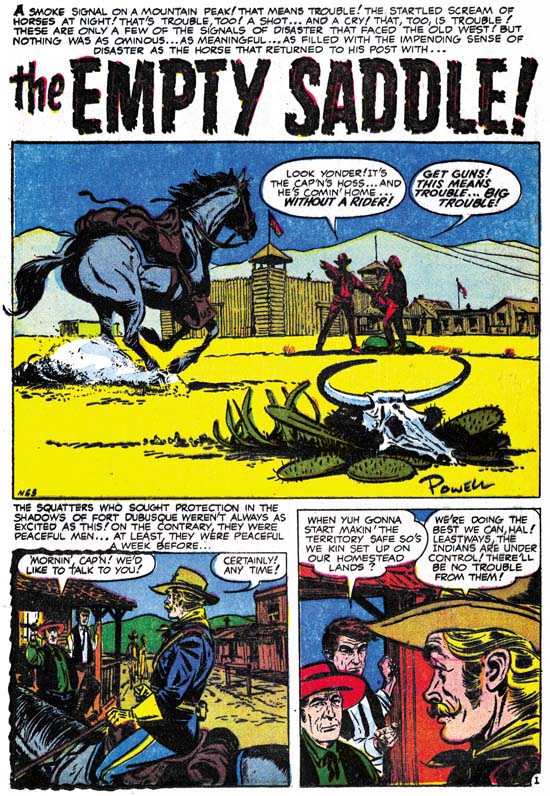

Black Rider Rides Again #1 (September 1957) “The Empty Saddle” page 1 art by Bob Powell

Besides the Kirby Black Rider stories, this comic also includes a short non-Black Rider story drawn by Bob Powell. Now Powell was a very prolific artist and I have only seen a small fraction of his work. I know it is not what he is famous for, but he did some gorgeous art for various Harvey romances. Everything I have seen by him has always impressed me. That is up to now. I got to say I really do not care for the art done in this particular story. Still it is a nice splash panel.

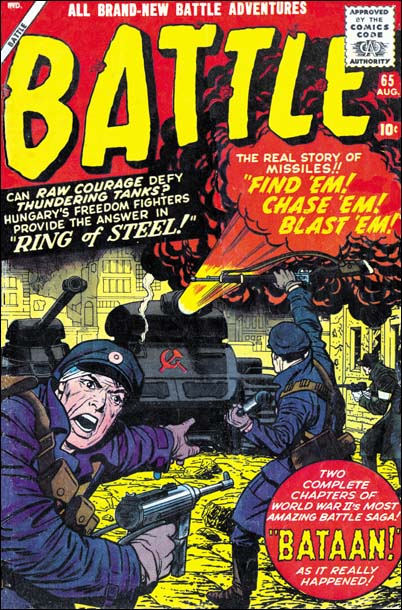

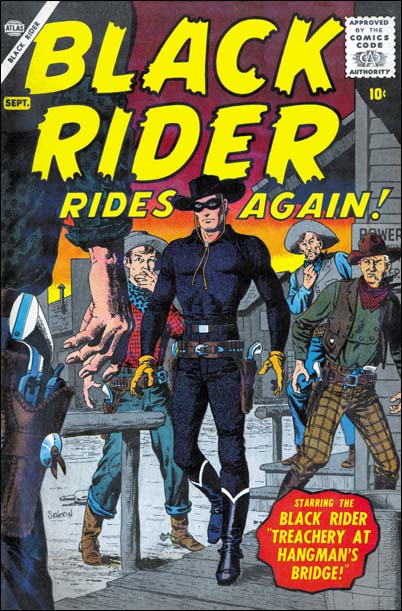

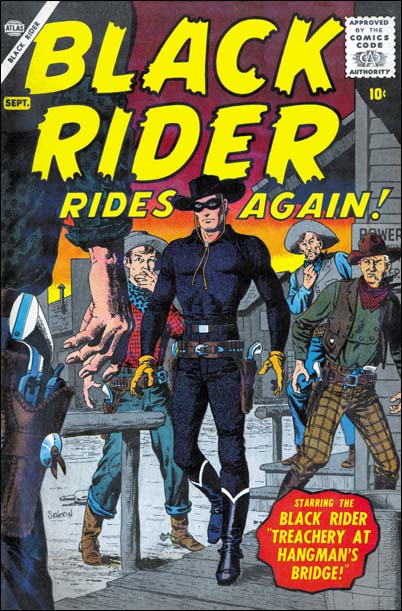

Black Rider Rides Again #1 (September 1957) cover art by John Severin

Jack Kirby only did a small amount of work for Atlas prior to the Implosion, my database shows 20 stories. What Jack did not do was any covers. I find it surprising that even though Kirby would do all the main stories for Yellow Claw and Black Rider Rides Again, someone else would do the covers. For Black Rider it was John Severin. I guess I really am supposed to say what a fine artist John was. But in all honesty I find most of what he did in this period rather dry. For me this cover is one of his better efforts.