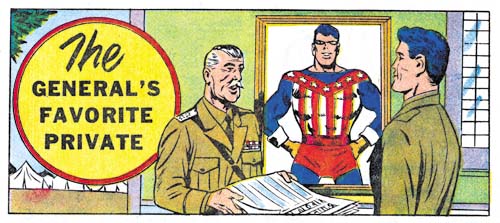

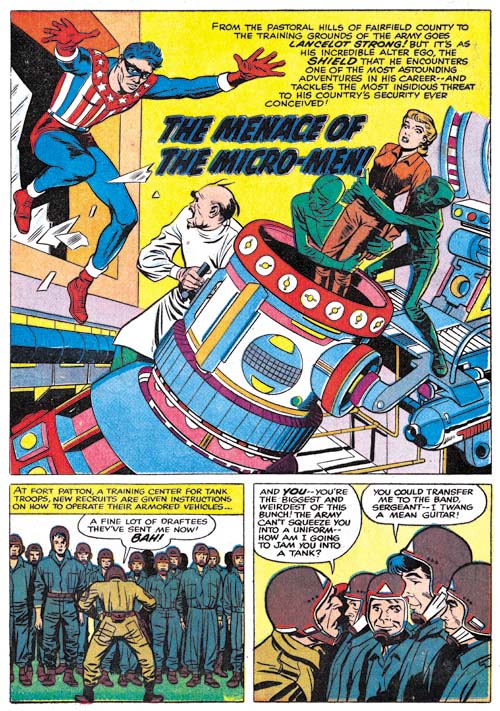

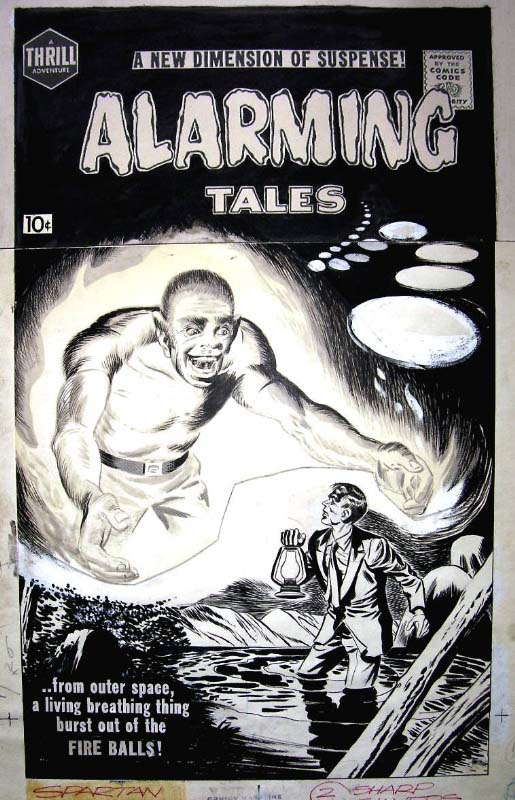

Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) “The Strange New World of the Fly”, pencils by Jack Kirby

Recently I posted about Jack Kirby’s work on the origin story of Private Strong, aka the Shield. In Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) Jack also had the honors of doing the same for the other new Archie hero, the Fly. Only in this case Kirby based the story on art that C. C. Beck did for the unpublished Silver Spider. Some have called the Silver Spider a Simon and Kirby creation but that simply is not true. Kirby had nothing to do with the Silver Spider which was a creation of Joe Simon, C. C. Beck and Jack Oleck. When I previously discussed the Silver Spider (The End of Simon & Kirby, Chapter 10, A Fly in the Mix) I dated this creation as 1953. To be honest I no longer remember where I got that date but it is not an unreasonable one. This would put it during the time of the Simon and Kirby collaborations but in “The Comic Book Maker” Joe writes about how the Silver Spider was created as a favor to Beck. An examination of xerox copies of the original art confirms Kirby’s absence.

Tommy Troy was an orphan like Lancelot Strong but the resemblance ends there. We meet Tommy in an orphanage but he ends up hired out to an elderly couple. Not kindly Kent-like farmers, but a mean, elderly couple with a reputation of dabbling in magic. Beck’s Silver Spider story had included a genie to add an element of humor, but Kirby has dispensed with him. However concept of a young boy who transforms into an adult superhero was Beck’s who repeated it from Captain Marvel.

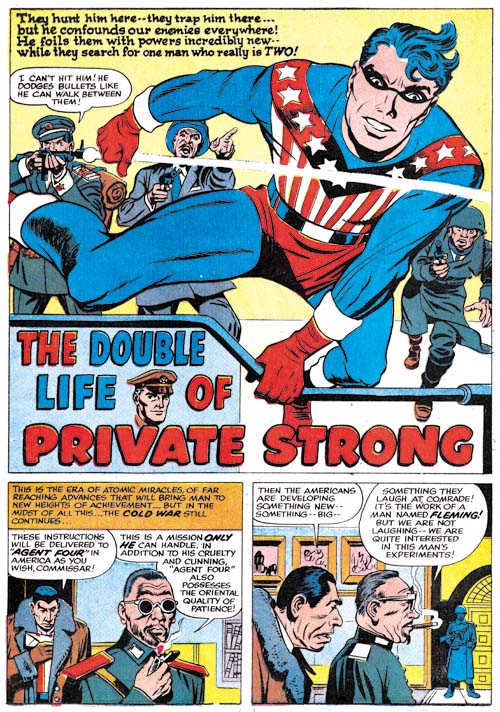

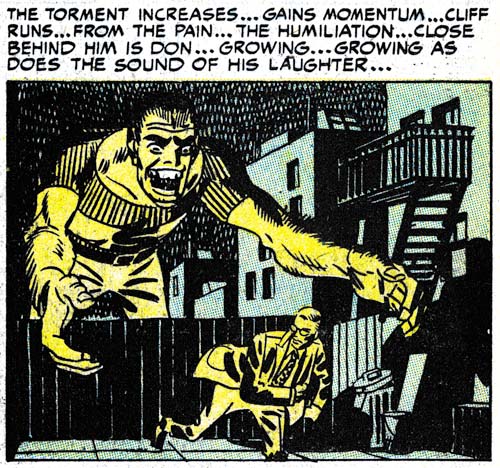

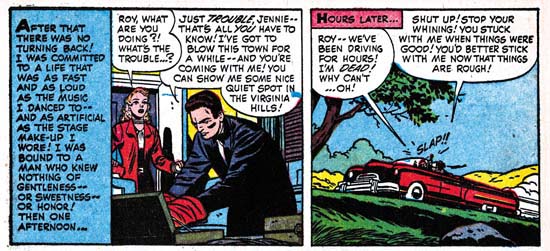

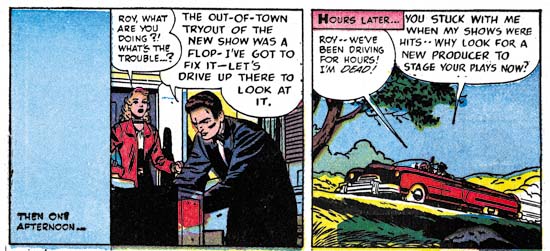

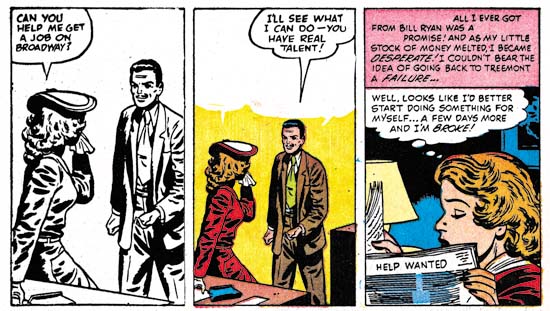

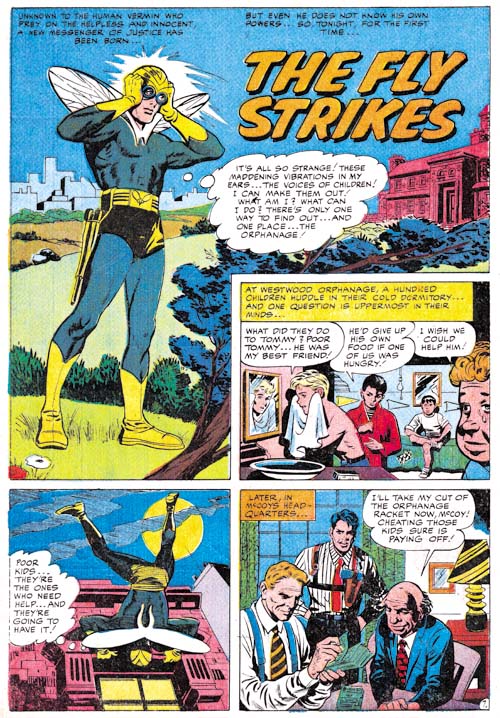

Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) “The Fly Strikes”, pencils by Joe Simon

Just like in Private Strong, the origin story for the Fly is actually told in a series of separate stories. The first one ends with the Tommy Troy being given a magic ring and transforming into the Fly. The second, “The Fly Strikes”, tells of the Fly’s first combat against criminals. This second story is actually based on the end of the origin story that Beck drew.

“The Fly Strikes” is generally credited to Jack Kirby but I am not convinced. I suspect that it is another case of Joe Simon swiping from and imitating Kirby. Joe was particularly good at doing this. Note the Fly peering into the window in the second story panel. This is a swipe from Fighting American #1 (Captain America Returns). I have no indications that Kirby was working from layouts in the stories that he did for this issue. Nor do I believe Jack would bother to swipe from himself. Why would he when he could do it much faster without a swipe? So as I said I believe this story was actually done by Simon.

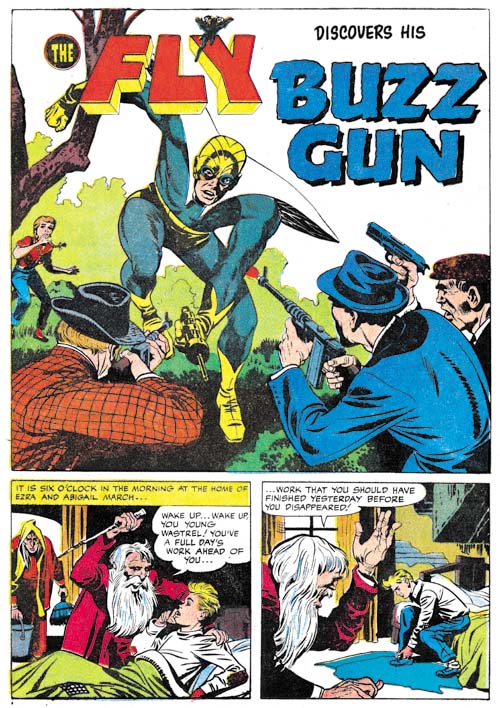

Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) “Buzz Gun”, pencils by Jack Kirby

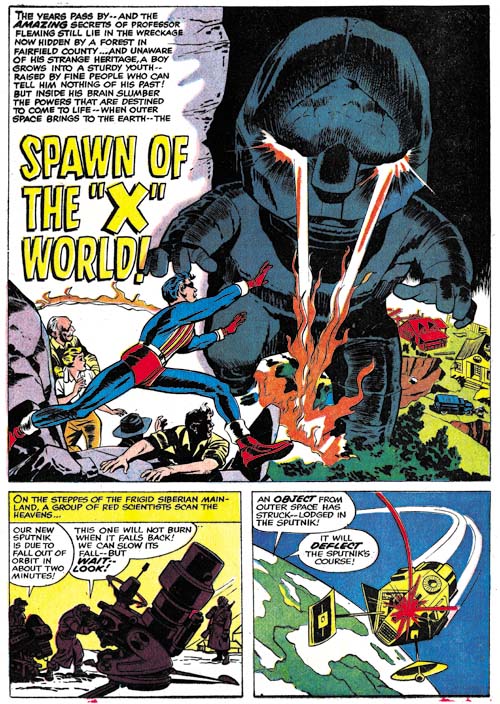

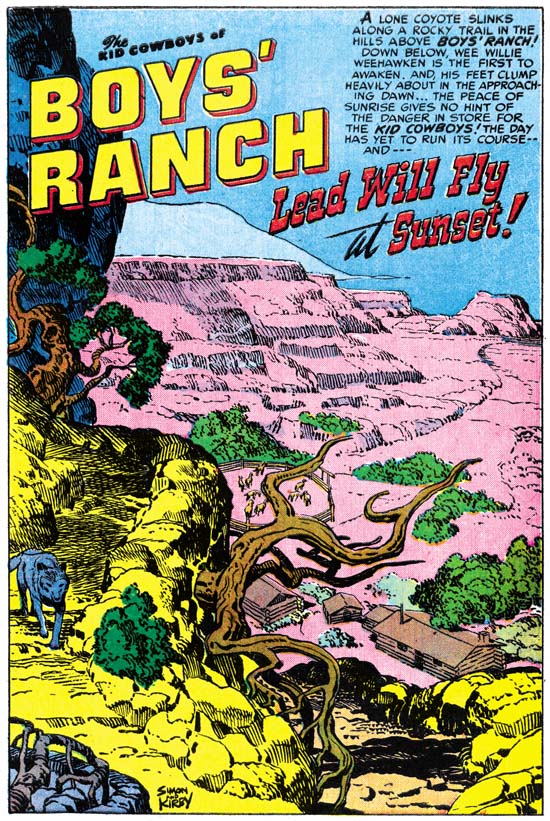

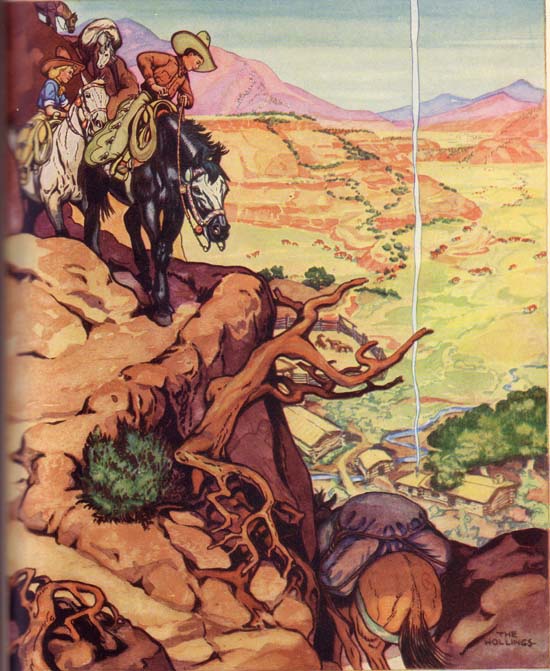

While the origin story came from Beck’s Silver Spider and the Fly’s powers seemed to be based on directives from Joe Simon, the Fly’s costume is derived from the Night Fighter, a Simon and Kirby creation that was considered for Joe and Jack’s publishing company, Mainline, but never used (Night Fighter, an Abandoned Superhero). Two characteristics stand out. One was the goggles. Similar eyewear appeared in the Black Owl from 1940 and 1941 (Simon and Kirby’s Black Owl). The presence of these goggles in two superheroes with a night theme suggests they were meant to be an aid for seeing in the dark. Of course such night vision would not be that appropriate for the Fly nor is it a power that the Fly ever used. Perhaps the eyewear was nothing more then a visual reference to the insect’s compound eyes or perhaps Jack saw no reason to remove them when he based the Fly’s costume on that of the Night Fighter.

One of the other features that the Fly inherited from the Night Fighter was a pistol of some kind. All that remains of the art for Night Fighter are two unfinished covers and neither offers any clues as to what use the pistol was put to. My guess is that it was for shooting a wire for scaling buildings such as that used by the Sandman, another superhero that Simon and Kirby worked on during the war. While a wirepoon might be a useful device for the Night Fighter it would be rather superfluous for a superhero like the Fly who is able to walk up walls. Well in “Buzz Gun” Kirby shows how the Fly’s pistol is used. It makes a noise! Oh well.

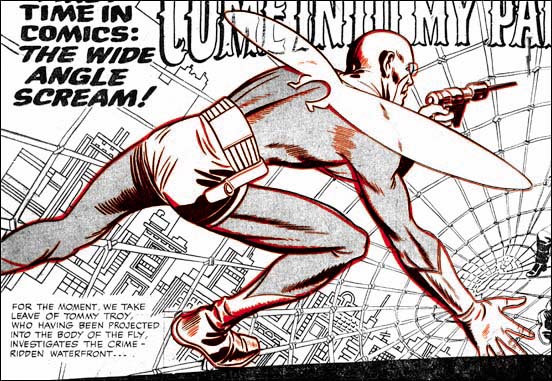

Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) “Come Into My Parlor”, pencils by Jack Kirby

Larger Image

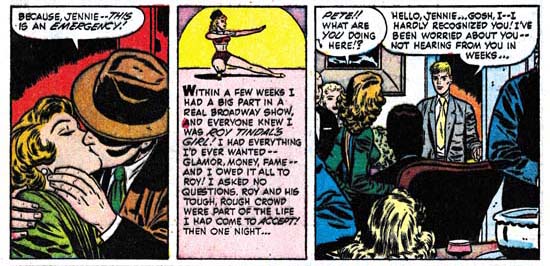

Jack Kirby’s last chapter for the origin story opens with a spectacular double page splash. The title exclaims “for the first time in comics: the wide angel scream”. Of course this really was not the first use of a double page splash a subject that I covered in a still unfinished serial post (The Wide Angle Scream). The chances are that none of the Fly readers had seen any of Simon and Kirby’s earlier uses. While Simon and Kirby did not originate the double page splash, nobody else did it better. Further by 1959 the wide splash was no longer used by anyone. I can imagine the impression the centerfold splash made for potential buyers of the comic. How could they resist. I am sure I would not have. I would have been 9 at the time but sometime around that period I had read some of the DC superhero comics. I found them boring and had given up on comics for a while. Unfortunately I never saw any of the Simon and Kirby creations.

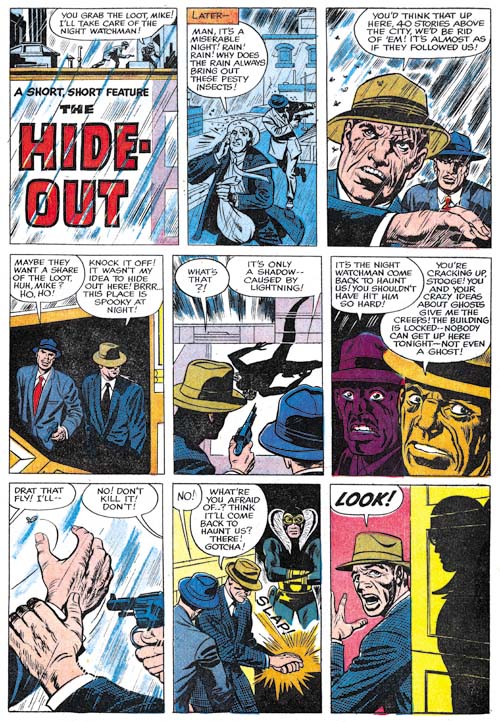

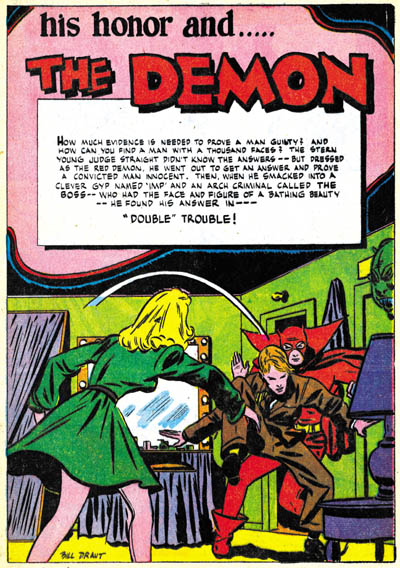

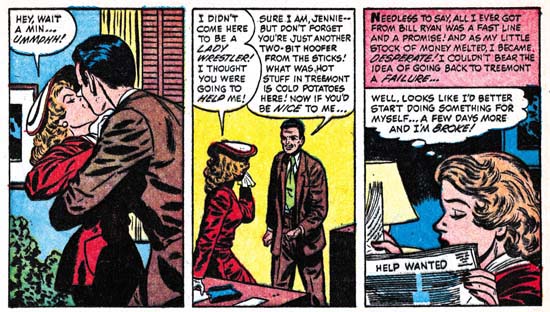

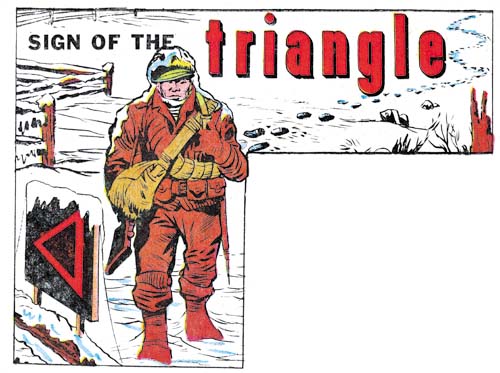

Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) “Sign of the Triangle”, art by Joe Simon

The Jack Kirby Checklist includes this among the work that Kirby did for this issue but I am not convinced. To me it looks like Simon did the drawing. However this confusion is really understandable because the illustration appears to be a swipe from the cover of Foxhole #3 (February 1955) which had be drawn by Kirby. It is not an exact copy, but I do not believe Simon ever did exact copies. The inking looks like Joe did that as well.

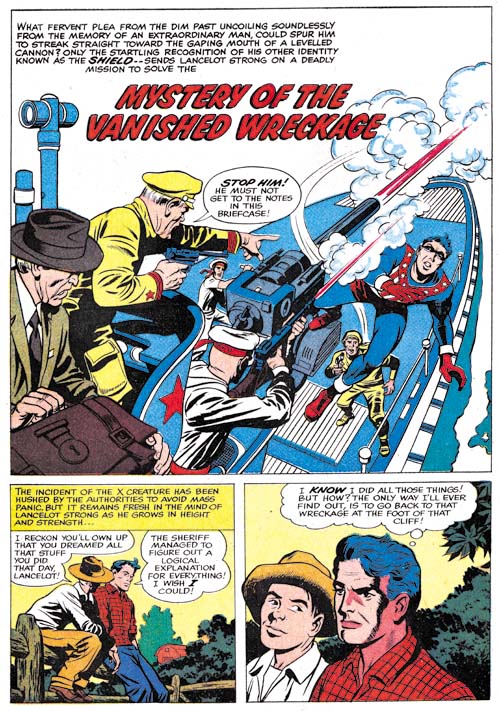

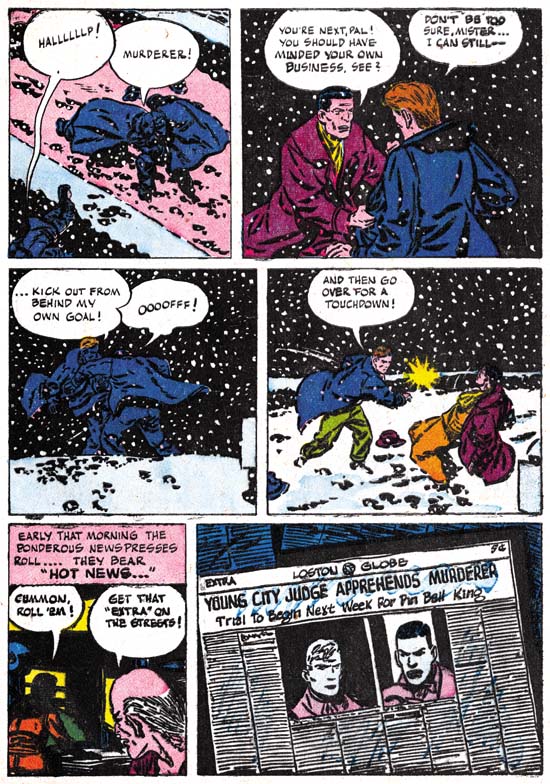

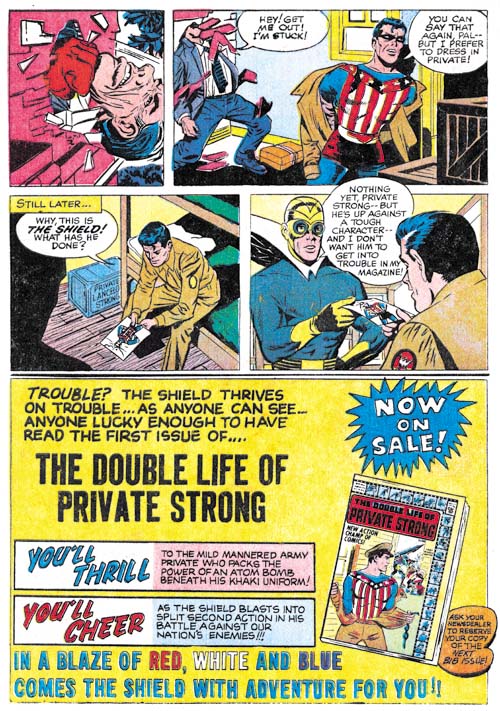

Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) “The Search”, pencils by Joe Simon

I may not be confident about attributing the illustration for “Sign of the Triangle” to Simon but there seems little doubt that Joe did the two page Shield promotional piece called “The Search”. This one is full of swipes from art by Kirby. For instance the man being punched through a wall and then left hanging was from the origin story in Fighting American #1 (April 1954, Captain America Returns). Note that while Joe follows pretty closely the man stuck in the wall he has added the man’s face for the punching image which Jack had cut off by the panel edge.

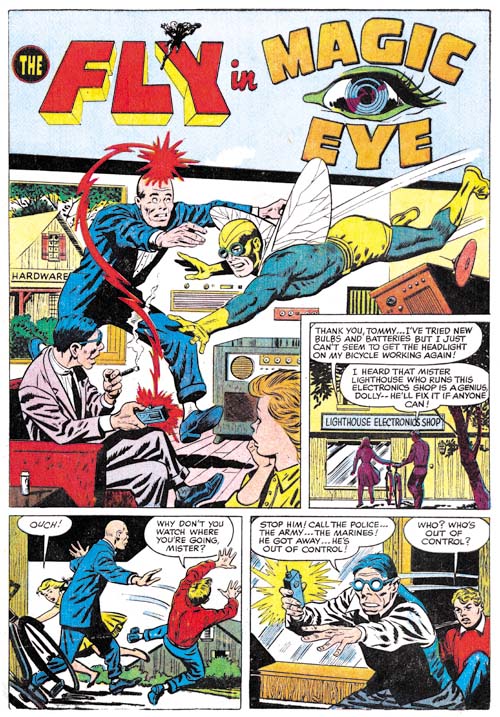

Adventures of the Fly #1 (August 1959) “Magic Eye”, pencils by George Tuska?

The final story is completely independent from the Fly origin and done by another artist, I believe it is George Tuska. I questionably attributed some work from Private Strong #2 to George as well; let us see if some of my more knowledgeable readers will agree with me on this one as well. This is another example where I do not see any obvious swipes of Kirby.