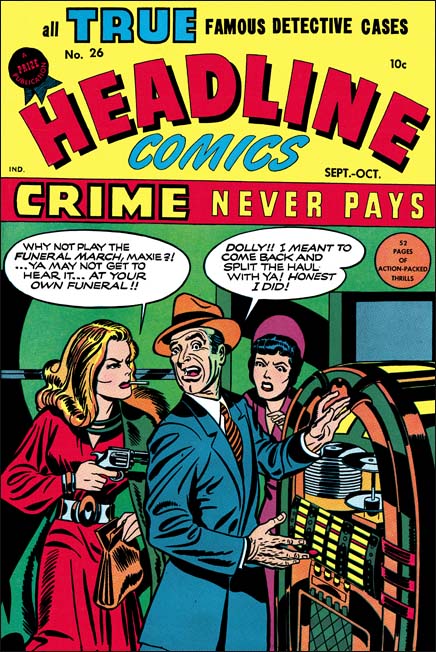

If I were writing this serial post based on the amount of material produced for the Prize crime comics, Ted Galindo would have had the third chapter ahead of Bill Draut. Although he worked on Prize crime comics for just a little over two years he was quite productive during that time. Some issues even had two stories drawn by this artist. Most of Ted’s art appeared in Justice Traps the Guilty because the other Prize title, Headline, was cancelled only two issues after Galindo started to provide work.

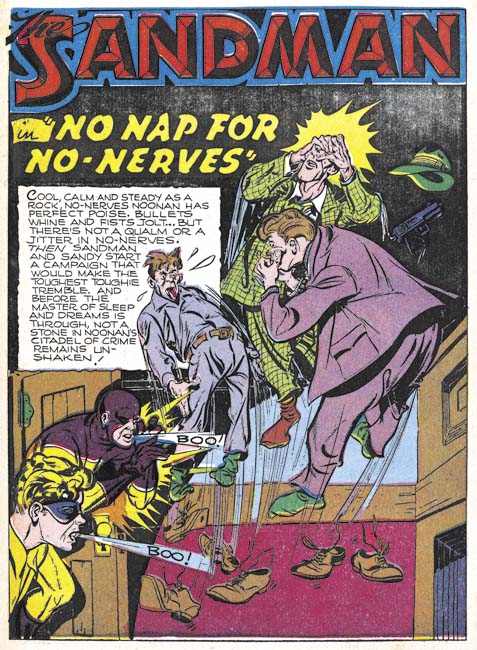

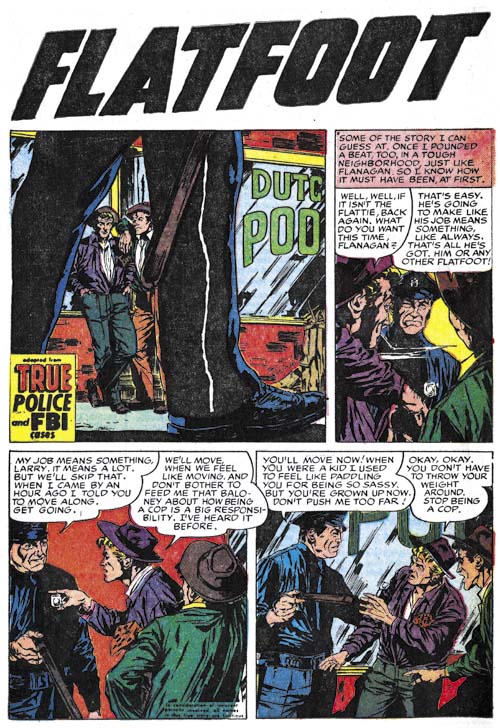

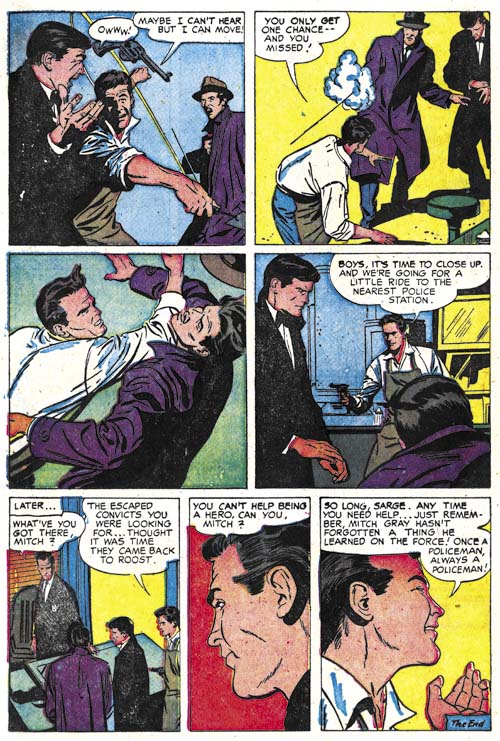

Justice Traps the Guilty #68 (November 1954) “Flatfoot”, art by Ted Galindo

Galindo’s first piece for Prize Comics was “Flatfoot” from Justice Traps the Guilty #68 (November 1954). This was even before “It’s Mutual” that he did for Foxhole #4 (April 1955). The earliest listing for Ted in the GCD is February 1955 so it is possible that “Flatfoot” is Galindo’s earliest published comic book art (or not, the GCD is a work in progress and is not always accurate). In this early piece, Ted is already an accomplished artist but has not arrived at his more distinctive style. The most significant difference is the much heavier inking. His later work would have a minimum of spotting but blacks played an important part of the art in “Flatfoot”. Ted’s predilection for splashless stories is also suggested by the rather small splash provided in this story. Also already present is Galindo’s fondness for tall narrow panels.

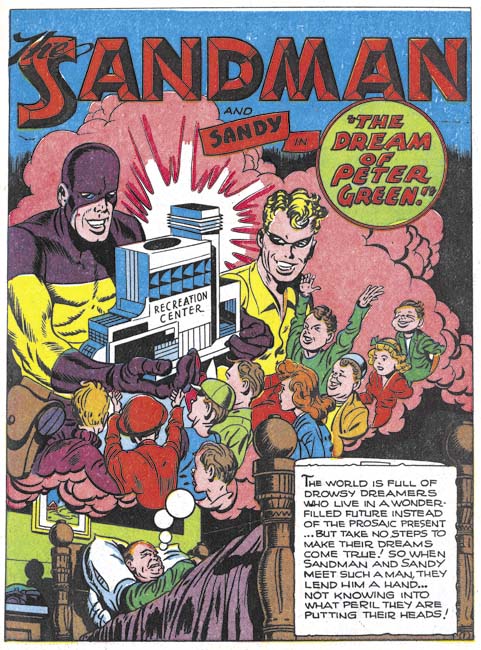

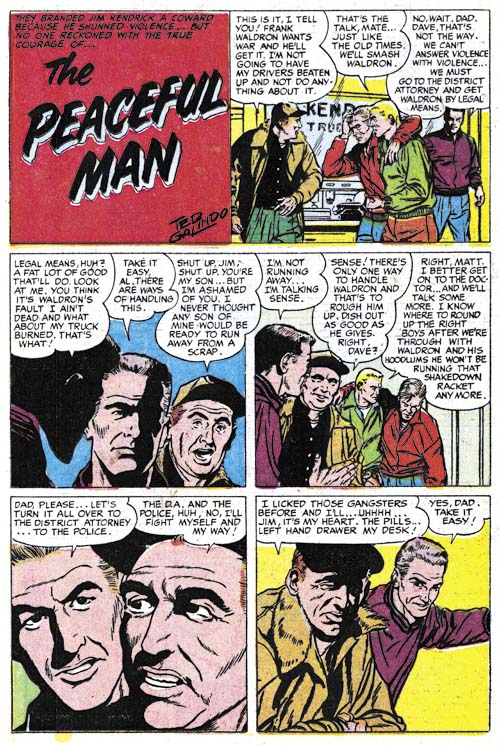

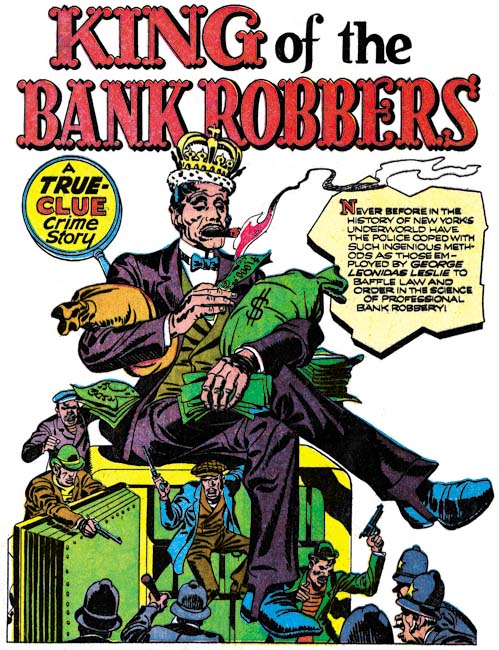

Justice Traps the Guilty #84 (December 1956) “The Peaceful Man”, art by Ted Galindo

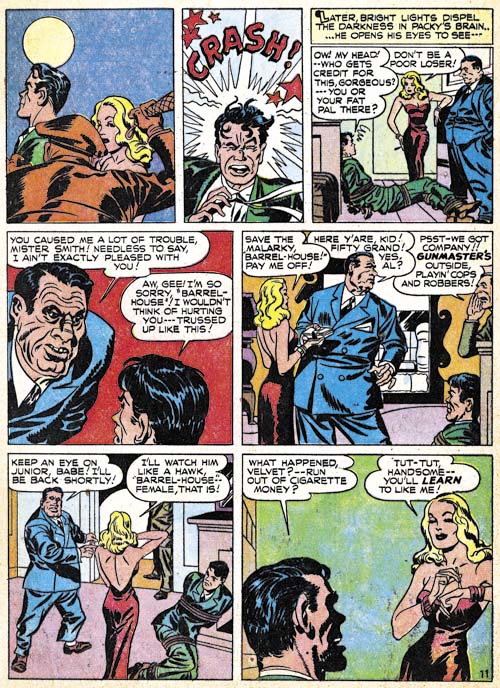

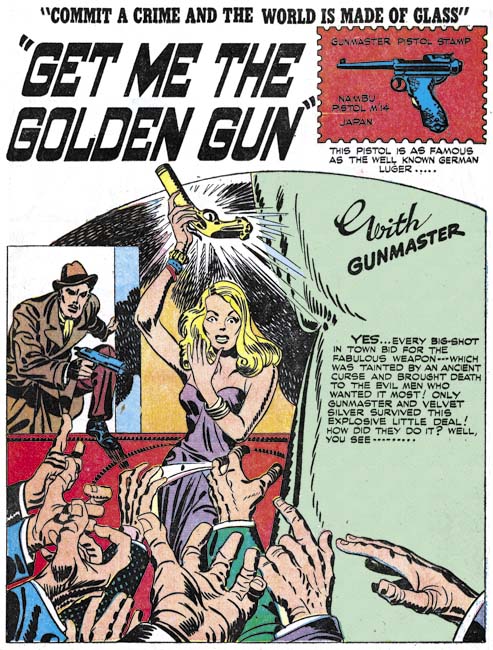

Galindo’s JTTG #68 work was not repeated and this artist would not reappear until “Flash Cameron Investigates a Disaster” for Headline #76 (May 1956). Judging from the GCD, Galindo had worked in the interim mostly for Charlton. With his reappearance in Prize Comics, Ted had fully arrived at his familiar style. Most of his stories would not include a splash panel but would instead start with a title panel no larger than the rest of the story panels. Since most artists in the Prize crime comics used half page splashes, Galindo’s format indicates that even though Prize artists were working from a script they still had leeway in the panel layouts. His inking would be light with minimum spotting. But when he used black it was usually in relatively large areas filled with ink.

Justice Traps the Guilty #85 (February 1957) “The Coffee Man” page 3, art by Ted Galindo

One of Galindo’s strengths was his adept characterizations. The post Comic Code Prize crime comics often included sequences of talking heads. with less talented hands these sequences could become rather boring, but Galindo’s carefully handling of the viewing angle and his effective emotional portrayals keep his stories interesting. On page 3 of “The Coffee Man” You can just feel the captain’s discomfort with a disagreeable duty. Even more importantly you can see Willie’s progression from a happy attitude to sadden realization that his life has been drastically offered. No blazing guns, but still a great piece of comic book art.

Justice Traps the Guilty #87 (June 1957) “Wall Of Silence” page 6, art by Ted Galindo

While Galindo could handle emotional portrayal he was no slouch when it came to action. As the example from “Wall of Silence” shows, this was not Kirby action. Frankly I am not sure where Galindo drew his inspiration, perhaps from Alex Raymond’s syndication strip Rip Kirby.

Justice Traps the Guilty #89 (October 1957) “The Printed Word” page 4, art by Ted Galindo

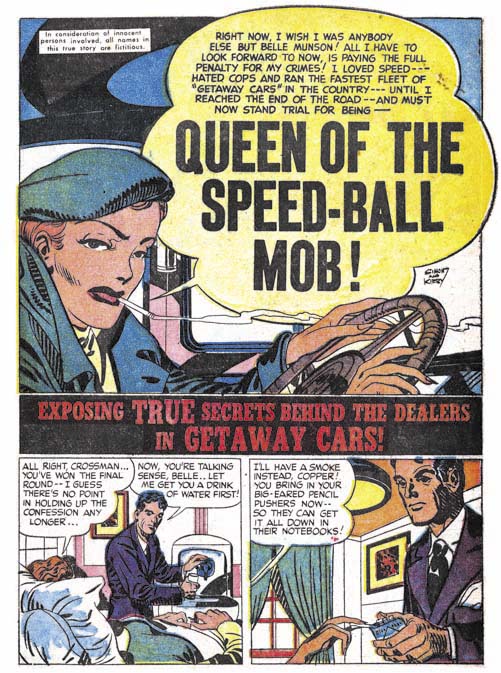

Generally Galindo’s strengths lay in his careful handling of talking heads and action, but in “The Printed Word” he shows how well he could do suspense. And it is not just page 4, the whole story is filled with effective drama. Ted’s use of blacks plays a important roll in the telling of the story. Note in particular how sinister the assailants shadowed face is in the final panel. The 50’s were important years for Alfred Hitchcock with such movies as “Strangers on a Train”, “Dial M for Murder” and “Rear Window”. I am sure Galindo was paying attention and that Hitchcock was an important influence, particularly for this story.

Justice Traps the Guilty #91 (February 1958) “G-Man Justice”, art by Ted Galindo

As I mentioned earlier, most of Galindo’s crime stories do not include a splash. “G-Man Justice” is one of the rare exceptions. During most of the later history of Justice Traps the Guilty Marvin Stein was the primary artist and would provide the cover and the lead story. But during the end of the run Stein’s prominence was replaced by other artist. This provided Galindo with the opportunity to provide a lead story. But a lead story had to have a splash and I suspect this is why Galindo provided one for “G-Man Justice”. It is not a bad job, but in all honesty it is not that great either.

Ted Galindo did a lot of romance art first for the Prize love comics not produced by Simon and Kirby (All for Love and Personal Love) and later in all the titles edited by Joe Simon alone. I have discussed this work in the final chapters of the Art of Romance (Chapters 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 and 38). Galindo’s romance work was rather nice, but it is his crime art that really shines. Ted also did work for the re-launched Black Magic. Hopefully someday I will write about that title as well.

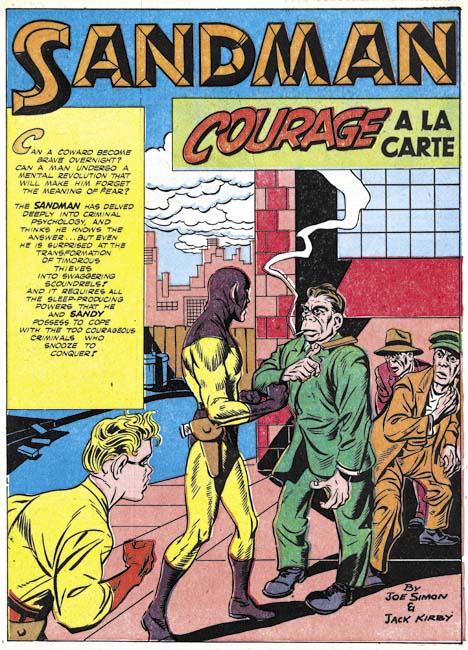

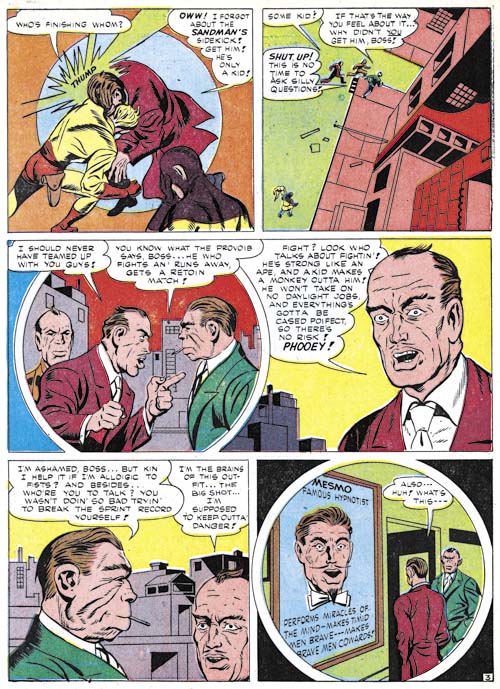

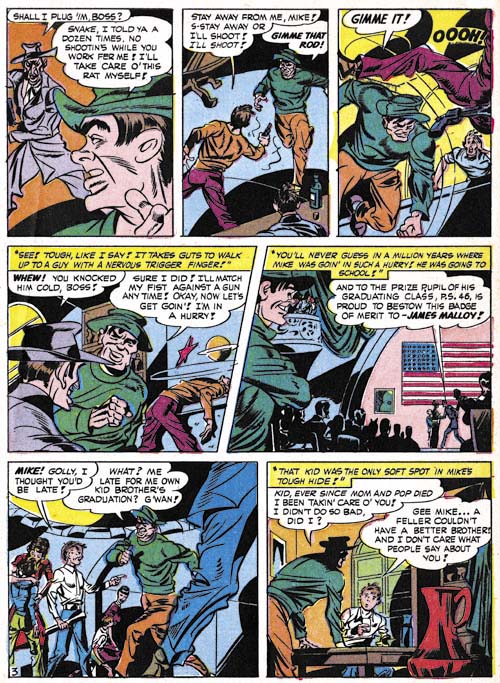

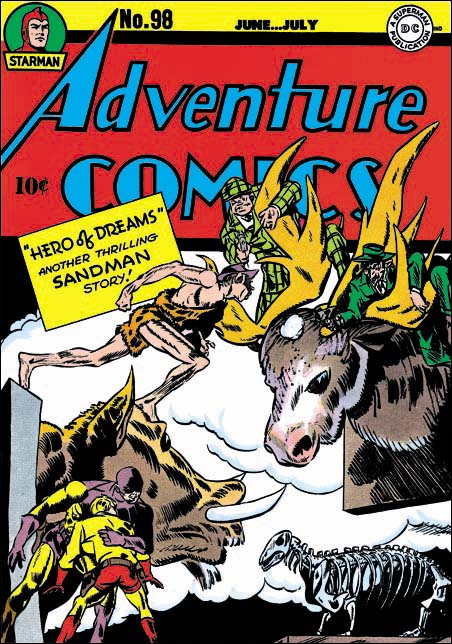

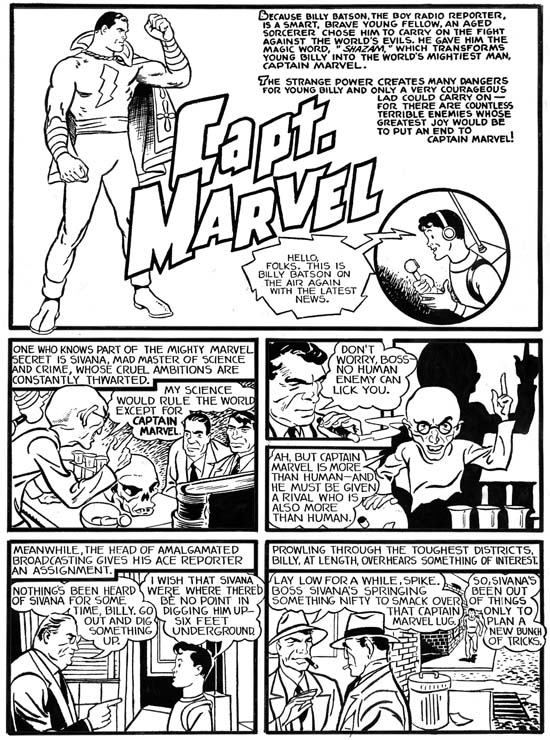

Captain Marvel, Special Edition (March 1941) bleached page art by Jack Kirby

Captain Marvel, Special Edition (March 1941) bleached page art by Jack Kirby