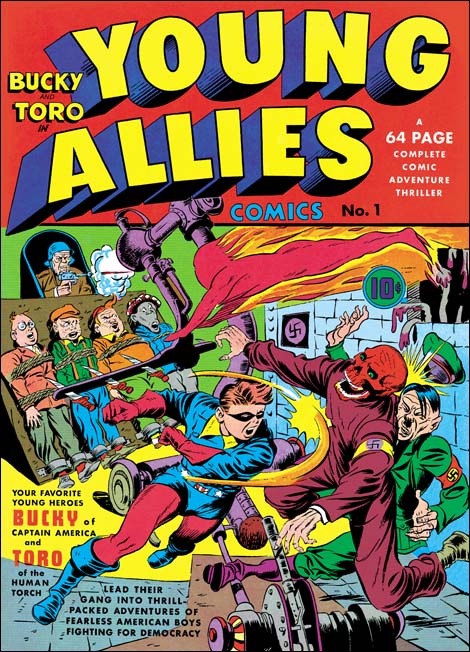

Young Allies #1 (Summer 1941) pencils by Jack Kirby

Simon and Kirby had a tendency to do things in a big way. If they drew a guy running they would portray him with his legs so widely separated that it would almost look like he was executing a split. A full splash page might not be enough for Joe and Jack and they would use two pages for a splash. Their motto seemed to be take things to the extreme. One of the things that they pushed was the story length. Simon and Kirby stories were often a few pages longer than their contemporaries, but that is not what I am referring to. Sometimes Simon and Kirby would create stories that extended to much greater lengths.

The first occasion for Simon and Kirby to execute a long story was Young Allies #1 (Summer 1941). I have written about this comic before (Young Allies and the L Word). Only most of the splash pages seemed to have Jack Kirby’s directly involved while the rest of the story appears to have been executed by a number of different artists. Still it is obvious that Simon and Kirby were the guiding hands. The story is divided into 6 parts that are referred to in the comic as chapters. While it was described as “a complete comic adventure thriller”, designating the parts as chapters indicates that Simon and Kirby had the idea of a novel very much in mind.

Simon and Kirby did not call Young Allies #1 a graphic novel but should we? But to answer that question we need to know what the definition of a graphic novel is. Despite the common use of this term in recent years there is a lack of agreement about what constitutes a graphic novel. Is it the length or the subject matter? Is a lengthy sequential graphic story sufficient or need text be present? Does the text have to appear in word balloons? I could go on but the point is there is no generally accepted definition of a graphic novel except perhaps it has to be lengthy. Actually I am not surprised by the difficulty in agreeing on a definition as aspects of cultural are often difficult to define. The reader might think they know what rock and roll is but in some cases it is hard to distinguish between rock and roll and blues, jazz or even classical music. Rather than trying to come up with yet another definition of what characteristics are fundamental to a graphic novel, I prefer to use a cultural definition. Today there are a lot of what are described as graphic novels but they all seem to trace their inspiration back to a number of works that appeared from 1976 to 1978 but especially Will Eisner’s “A Contract With God” (1978). A graphic novel should be part of that cultural tradition. In order to be a graphic novel a work should also possess some characteristics that distinguish it from other cultural objects, particularly comic books. Of course the work’s length is certainly an important factor.

It Rhymes With Lust (originally 1950, image from 2007 Dark Horse Reprint) art by Matt Baker

However there are older works that appeared before 1976 that have characteristics that distinguish them from normal comic books. For instance “It Rhymes With Lust” by Drake Weller, Matt Baker and Ray Osrin (1950) was 126 pages long and more like a pocket book in construction. Such productions would be called graphic novel precursors. The precursors may have had a spirit in common with the modern graphic novel but they were culturally dead ends which at the time had little impact. Was Simon and Kirby’s Young Allies #1 such a precursor? I think so but just not as good a precursor as others. Young Allies #1 was unique in that the entire comic was devoted to one story 57 pages long. Perhaps there were previous examples done by other comic book artists but I am not aware of them. Now 57 pages might seem much less than the 126 pages for “It Rhymes With Lust” but that is like comparing apples to oranges as the physical size of the two works are very different. The art found in Young Allies #1 was the size typical of comic books of the day, 6.5 by 9 inches. The art in “It Rhymes With Lust” was 4.5 by 6.5 inches. The total art area for Young Allies #1 was 3334.5 square inches compared to 3685.5 square inches for “It Rhymes With Lust”. The Young Allies had roughly only 10% less art. While Young Allies #1 was lengthy it was otherwise not distinguishable from standard comic books and was sold with them as well. Further it was meant for the same audience.

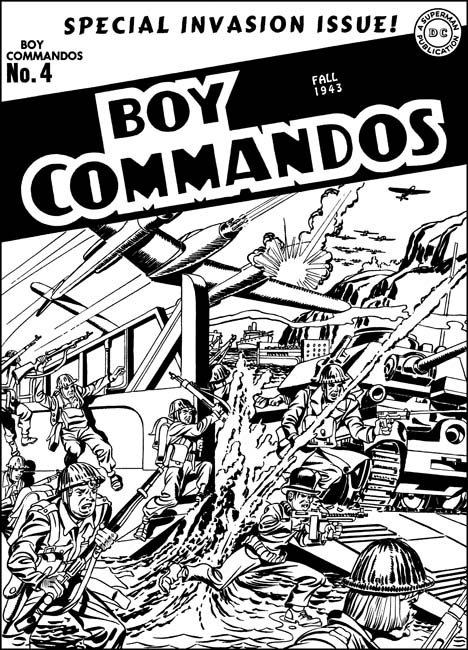

Boy Commandos #4 (Fall 1943) pencils by Jack Kirby

Simon and Kirby repeated the idea of a full length story in Young Allies #2 (Winter 1942). Shortly later Joe and Jack left Timely for DC and subsequent Young Allies returned to the standard comic book format of several individual stories. But Simon and Kirby had not discarded the idea of extended stories and returned to it for Boy Commandos #4 (Fall 1943). This time the cover reference was nothing more than “special invasion issue”. However it too was divided into six sections designated as chapters. Boy Commandos #4 had some single page fillers so although the Boy Commandos story occupied the entire book it was slightly shorter at 50 pages.

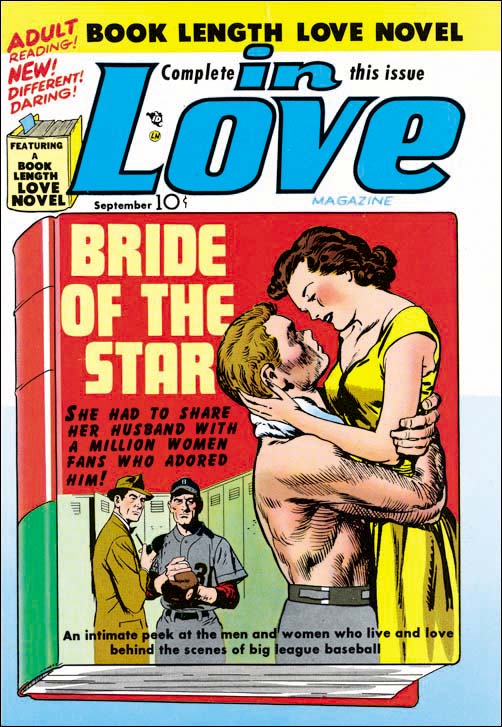

In Love #1 (September 1954) pencils by Jack Kirby and John Prentice

After Boy Commandos #4, the idea of a book length story went dormant but not forgotten. When Simon and Kirby created Mainline, their own publishing company, the romance title In Love declared at the top “book length love novel”. Technically this was inaccurate because the each issue contained six pages of other romance stories. But now Simon and Kirby actually called it a love novel and even included a book icon to make the connection clear. “Bride of the Star” (In Love #1, September 1954) had 20 pages in three chapters, “Marilyn’s Men” (In Love #2, November 1954) 19 pages in three chapters, and “Artist Loves Model” (In Love #3, January 1955) 18 pages in two chapters. The idea of a extended story was abandoned for In Love issues #4 to 6.

Double Life of Private Strong #1 (August 1958) pencils by Jack Kirby

In a way the idea of an extended story was still not completely abandoned by Simon and Kirby. The first issues of the Double Life of Private Strong and the Adventures of the Fly (both August 1958) included origin stories that were covered in several sections. However these sections were not named as chapters and no reference was made to their being novels or extend length stories.

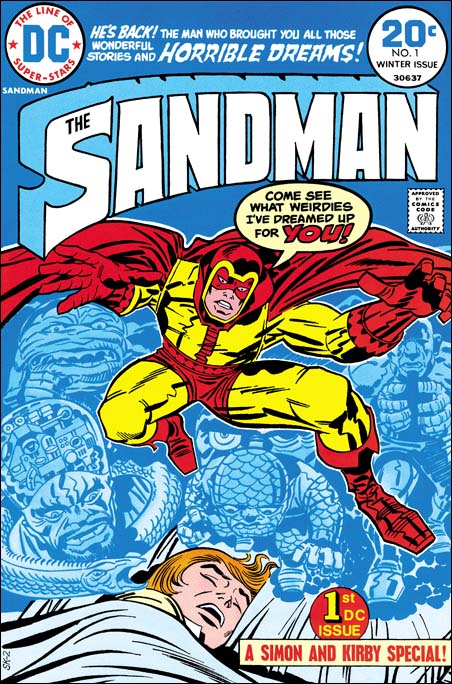

Sandman #1 (Winter 1974) pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Mike Royer

Simon and Kirby went the separate ways after Private Strong and the Fly until Carmine Infantino brought them back one last time for Sandman #1 (Winter 1974). Once again they turned to a comic length story, this time in two sections with a total of 20 pages. But comics had changed over the years and by 1974 comic length stories were not at all unusual. Simon and Kirby’s attempts to push the envelope of a comic story had been forgotten while true graphic novels would make an appearance a couple of years later.