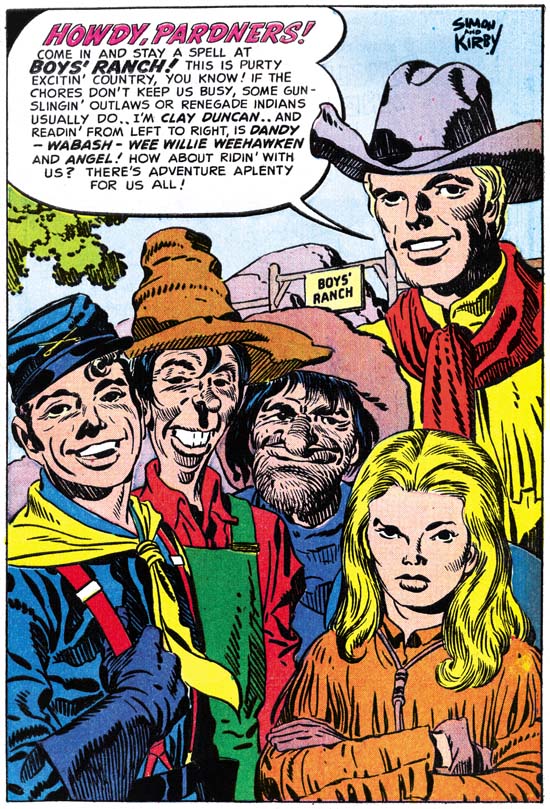

Boys’ Ranch can conveniently be separated into two groups. The first three issues featured work by Kirby (with one exception), had three stories per issue, and the stories were longer. For the final issues there is much less use of Kirby, only two stories per issue, and shorter stories. Actually each final issue had a single story, but broken into two chapters. It was part of the Simon and Kirby modus operandi to make heavy use of Kirby’s talents in the early issues of a new title and afterwards make more frequent use of other artists. For Boys’ Ranch the change seems much more dramatic then in other titles. The last three issues are good, but they are not the masterpieces that the earlier issues were.

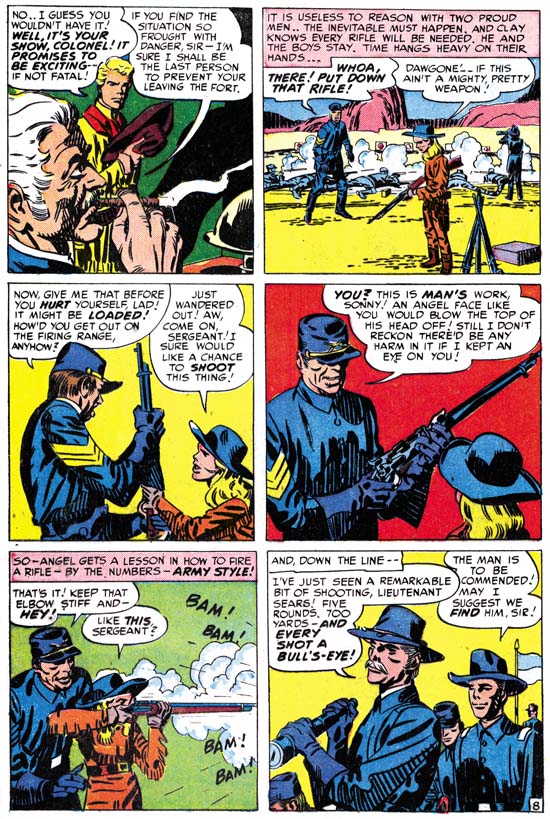

Boys’ Ranch #4 (April 1951) “The Bugle Blows At Bloody Knife”, pencils by Jack Kirby inks by Mort Meskin

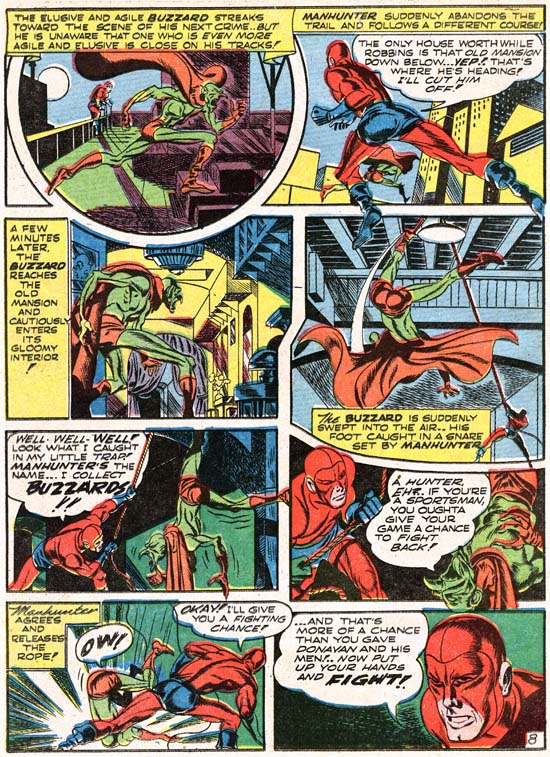

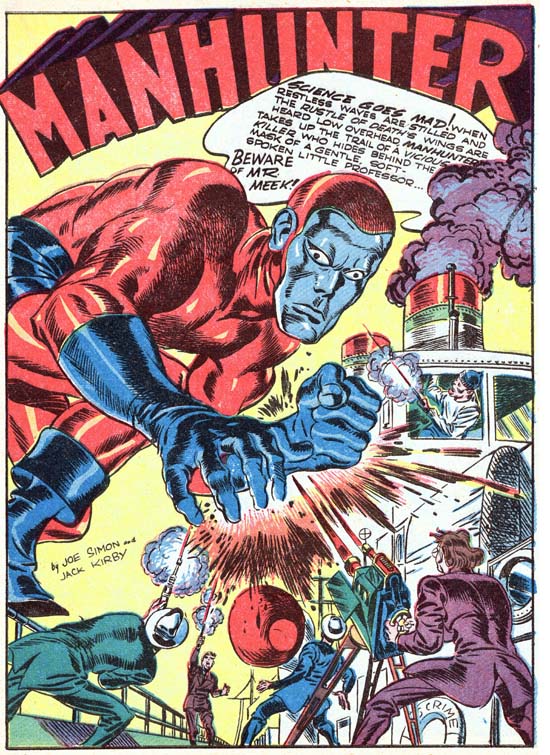

In the last three issues of Boys’ Ranch there is only one story completely penciled by Kirby, “The Bugle Blows at Bloody Knife”. However Mort Meskin does all the inking for this story other then the splash page (which looks like Kirby’s inking to me). Both “The Bugle Blows at Bloody Knife” and “I’ll Fight You for Lucy” are good references for Mort Meskins’s use of the Studio style of inking. For his own work Mort generally did not so fully use the Studio inking style and so his thorough adoption of it in Boys’ Ranch provided a more uniform appearance throughout the title. Mort’s inking is very distinctive and he was careful not to overwhelm Kirby’s pencils. Kirby characteristics such as his eyebrows are generally maintained. The two stories also provide good examples of the differences between Kirby’s way of graphically telling a story and that used by Meskin.

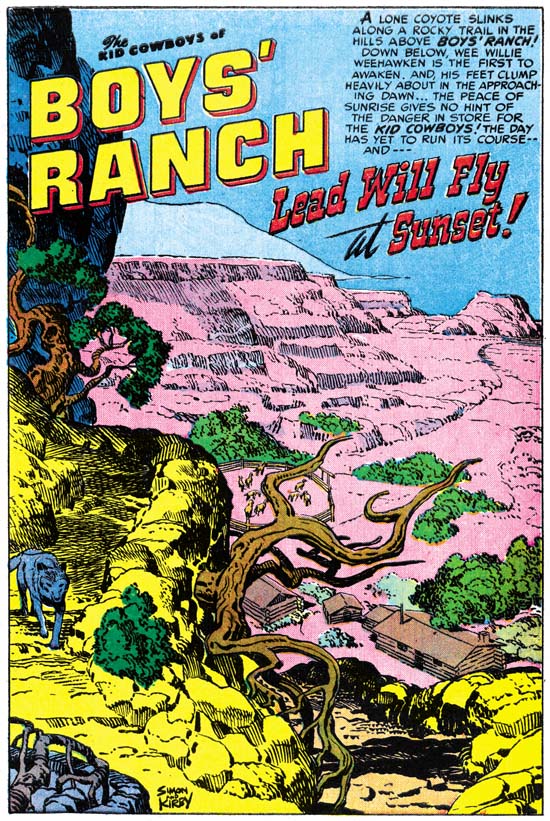

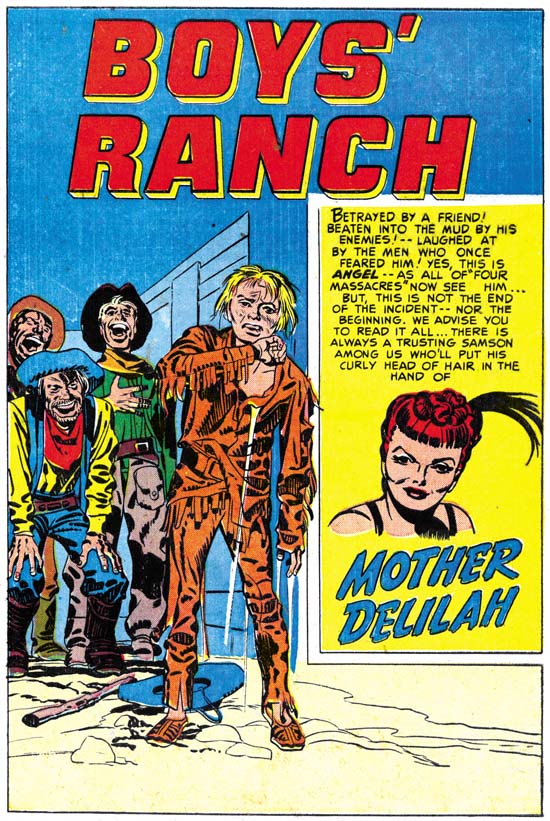

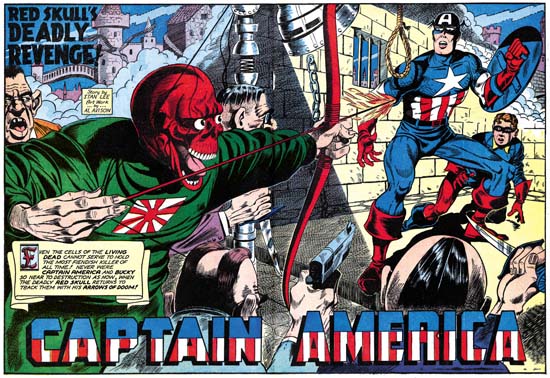

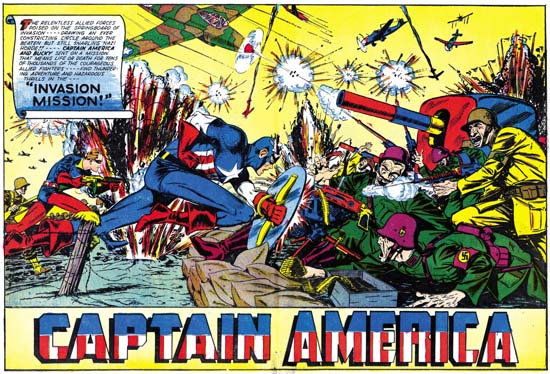

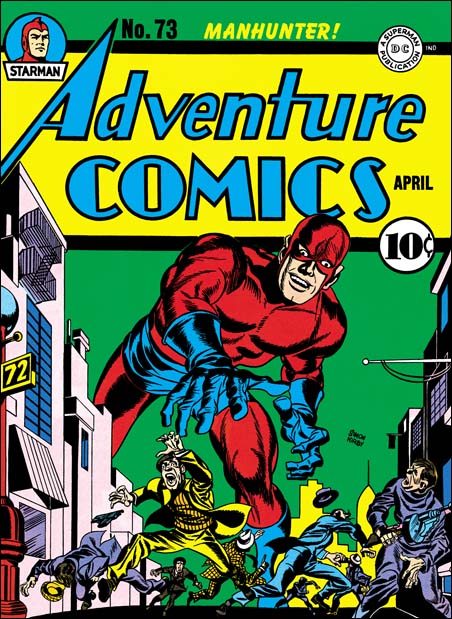

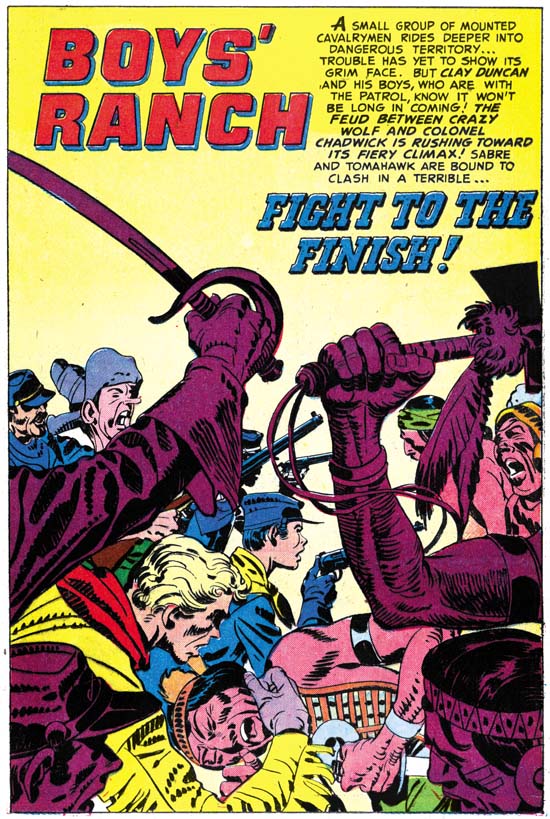

Boys’ Ranch #4 (April 1951) “Fight To the Finish”, art by Jack Kirby

Although Jack contributed less work for the title, care was taken for putting his efforts where they would be of the most use. One way this was done was having Jack pencil the splash page even for stories illustrated by others. With the exception of “I’ll Fight You for Lucy”, every splash in the Boys’ Ranch comics was drawn by Kirby and they are all full page splashes. What splash pages these are. “Fight to the Finish” is certainly among the best. It is a pure Kirby battle, up close and personal. To thrust the viewer into the action, Kirby creates a foreground showing only parts of some fighters. This is the same technique Jack used with a horse as seen in last weeks post and the Bullseye #7 double page splash. Here Kirby presents contrasting arms and heads. The antagonists are clearly identified by the officer sword versus tomahawk above, and below the soldier sporting a Calvary hat confronting an Indian warrior with suitable head apparel. The colorist wisely blocked the foreground elements in the same purple color. The background provides an only slightly better view of other contestants. Among some soldiers, we find Clay, Dandy and Wabash. Perhaps Angel had to be left out because even the truncated cast limited the number of Indians that could be included.

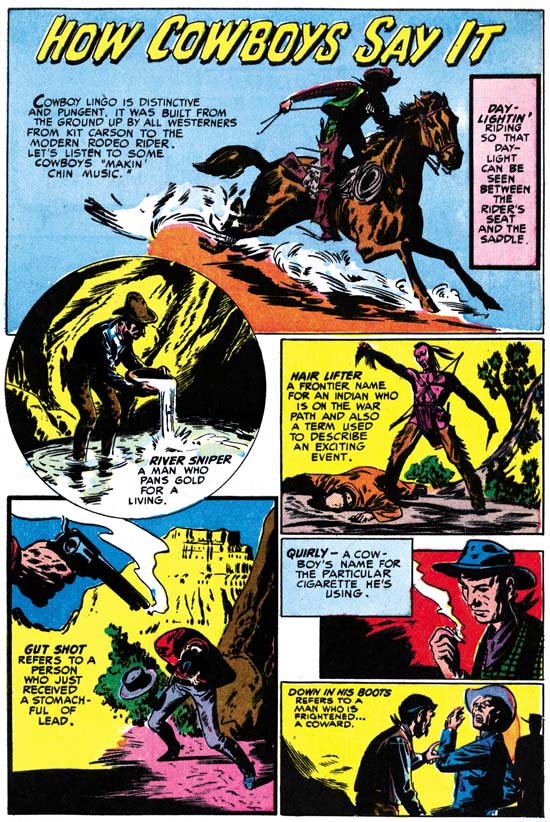

Boys’ Ranch #4 (April 1951) “How Cowboys Say It”, art by Marvin Stein

If Jack Kirby was used less in the final Boys’ Ranch issues the natural question then becomes who did the art? The Jack Kirby Checklist lists these stories as having a “Mort Meskin assist”. Well as we have seen Mort Meskin was involved with Boys’ Ranch so he certainly is a candidate to consider. The Marvel reprint volume lists the books creators as Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, Mort Meskin and Marvin Stein. So should we add Marvin Stein as a possible contributor? The earliest date that my database has for Stein is for Headline #40 (March 1950, “The Case Of Joe Andrews”). But I am not very confident of that attribution as it is unsigned and has only a passing resemblance to work by Marvin. The earliest dates for work more securely attributed to Stein would be the cover for Justice Traps the Guilty #20 (November 1950, unsigned) and “Brute Force” from JTTG #22 (January 1951, signed). These dates indicate that Marvin Stein was certainly available for work on the last issues of Boys’ Ranch. “How Cowboys Say It” was one of those single page contributions to the Boys’ Ranch title. In the panel for “Quirly” we find a cowboy viewed from above and to the side. This view along with the distinctive manner of handling the eyes and eyebrows indicates to me that this certainly was done by Marvin Stein. The inking was done in a manner typical of Stein’s work. Note the rather blunt brushwork and its often scribbly nature. Marvin did not adopt many features of the Studio style when inking his own pencils and this page from Boys’ Ranch #4 is no exception.

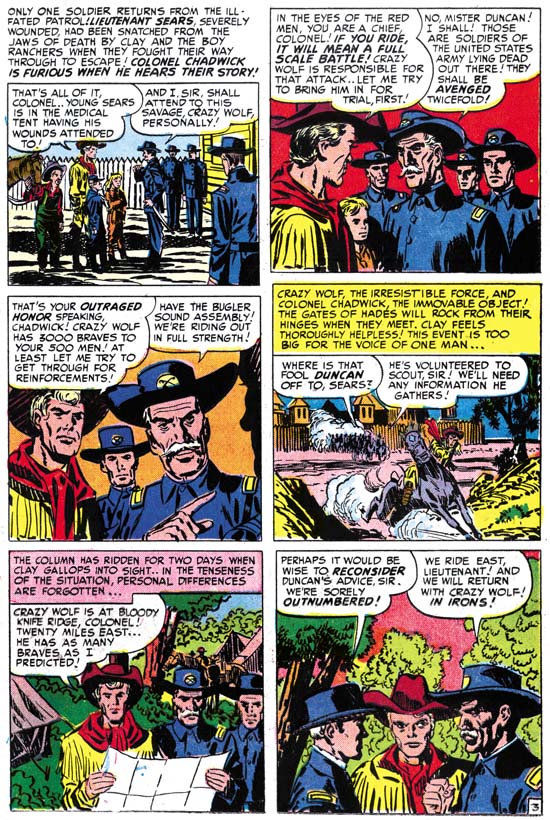

Boys’ Ranch #4 (April 1951) “Fight To the Finish” page 3, art by Mort Meskin? and unidentified artist

In my opinion, the story art for “Fight to the Finish” has only a passing resemblance to work by Jack Kirby. Take a look at panel 4 from page 3 (shown above). The horse’s front is angled in an opposite direction to its rider and posterior. I do not recall Kirby ever having drawn such an odd arrangement. In the first panel Dandy and Angel look much shorter as compared to Clay Duncan then either Jack Kirby or Mort Meskin drew them (although Wabash seems about right). The eyebrows, particularly in the second and third panels, have some of the angular nature typical for Mort Meskin. There are some aspects of the Studio style however the inking as a whole looks much too sloppy for Meskin.

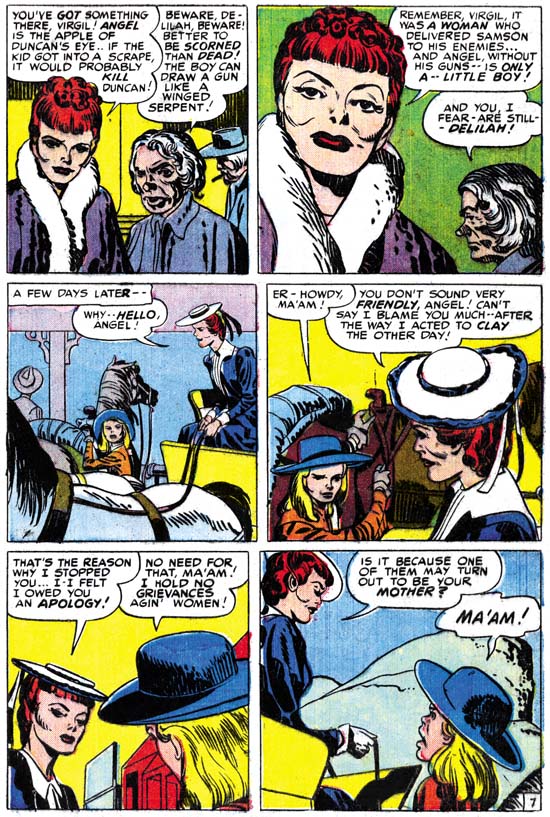

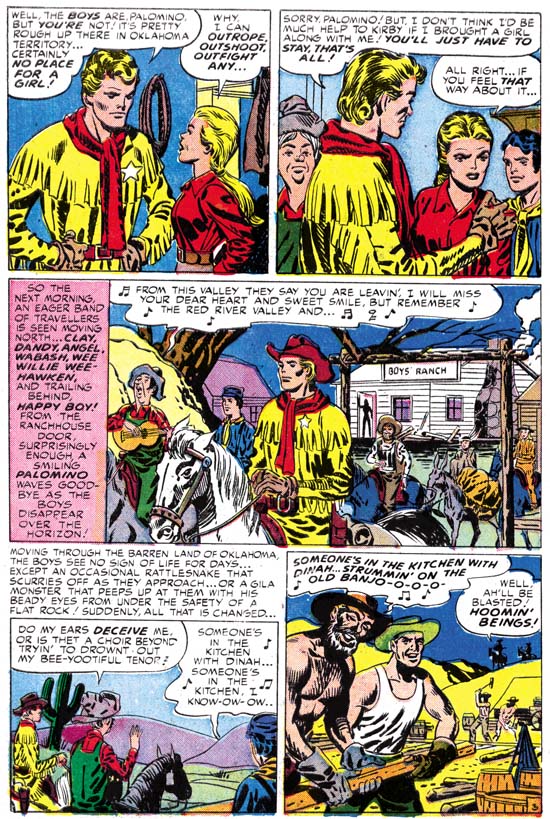

Boys’ Ranch #5 (June 1951) “Bandits, Bullets and Wild Wild Women” page 4, art by Mort Meskin? and unidentified artist

A similar situation is found in “Bandits, Bullets and Wild Wild Women” from Boys’ Ranch #5. Once again some of the eyebrows resemble Meskin’s mannerism. There are more techniques typical of the Studio style but it is still a rather sloppy performance not at all typical for Meskin. However I have seen Marvin Stein use the same coarse picket fence as evident on the back of Wee Willie Wheehawken. Most of the drawing is rather crude but look at Willie in the fourth panel. Willie is really nicely penciled and even the inking is not badly handled. The comparison of Willie’s portrait with how crudely the rest of the page was done suggests that there may be more then one hand working on this story.

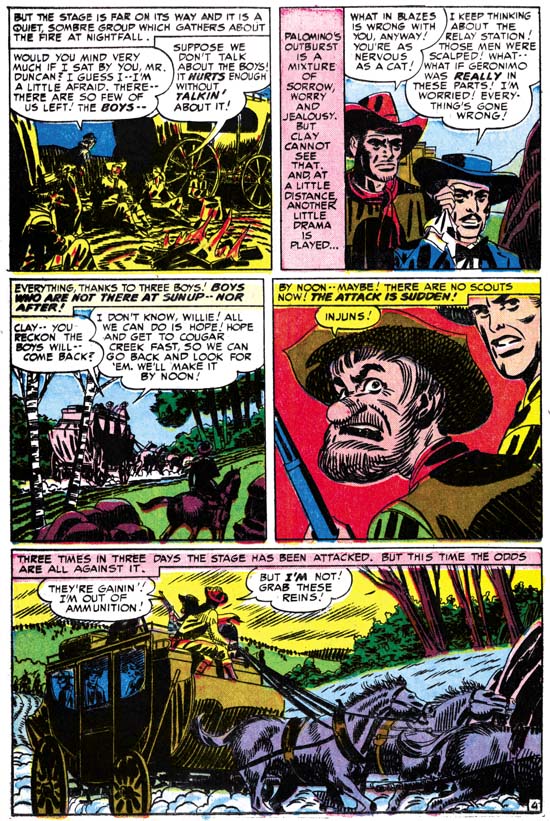

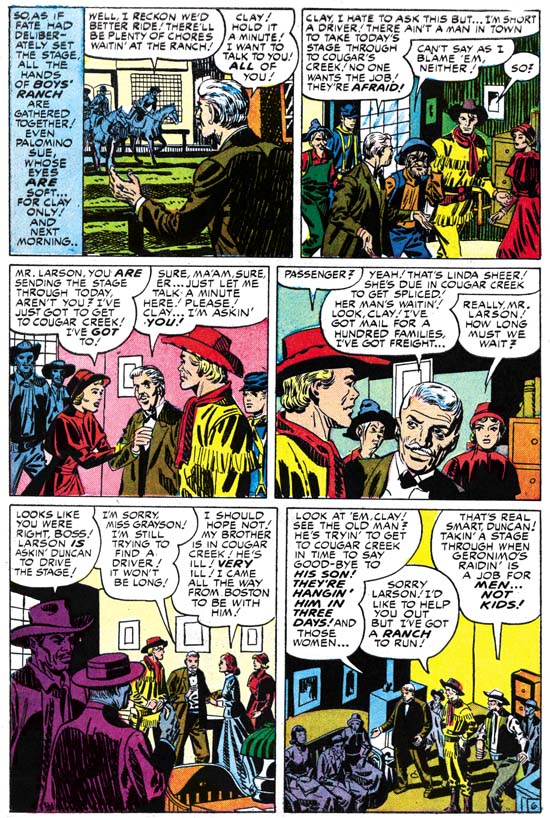

Boys’ Ranch #5 (June 1951) “Last Mail to Red Fork” page 4, art by Mort Meskin? and unidentified artist

Much of what was said previously can be applied to “Last Mail to Red Fork” as well. There is one spotting techniques that shows up more on this page then previous examples. Many of the cloth folds are constructed by multiple overlapping brushstrokes creating long narrow folds. This is a typical Meskin inking technique but its actual use here seems too poorly handled for Mort. Of particular interest is the punch thrown by Clay in the fourth panel. This is not at all the way Kirby would have done it so again I do not believe Jack even supplied the layouts. With Kirby the whole body responds when being hit with a fist, not just the head and arms as in this panel. Clay’s swing and Drapo’s response does look like Meskin’s style to me (see the page from Black Terror #23 from my last weeks post).

Boys’ Ranch #5 (June 1951) “Last Mail to Red Fork” page 6, art by Mort Meskin? and unidentified artist

One final example is from “Last Mail to Red Fork”. Here Mr. Larson from panel 4 distinctly looks like Meskin’s work and is much more carefully inked then most of the story.

So let me summarize my findings for “Fight To the Finish” (BR #4), “Last Mail To Red Fork” (BR #5), and “Bandits, Bullets and Wild Wild Women” (BR #5). In all cases the splash pages were by Jack Kirby, but he otherwise did not have any significant contributions to the art, not even providing layouts. Some of the fight scenes are done in a distinct manner that looks like the work of Mort Meskin. Mort’s touch is also apparent in some of the eyebrows. So I would say the pencils were done by Mort Meskin. Although some of the inking is done in a manner similar to Meskin’s technique on a whole it just seems too sloppy to have been Mort’s. However the inker does seem to have been following the Meskin’s directions. Could these stories have been inked by Marvin Stein? I really cannot say because Stein did not seem to use the Studio style for his own work and so I have little to compare these Boys’ Ranch inking with. So for the moment I am going to leave the question of inking attributions unresolved. But was the second artist just an inker or did he make a contribution to the drawing as well? My current inclination is to provide joint credits.

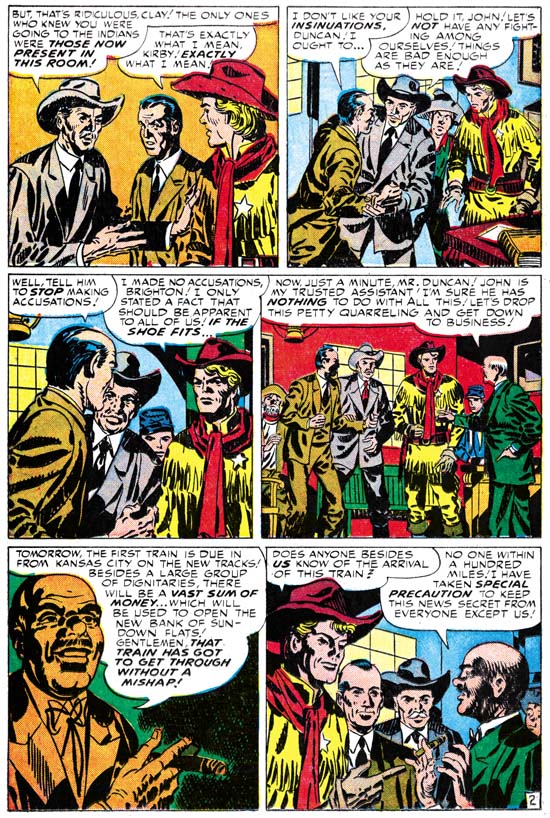

Boys’ Ranch #6 (August 1951) “Teeth for The Iron Horse” page 3, art by Jack Kirby and unidentified artist

The stories from Boys’ Ranch #6 have a much more Kirby feel to the layouts. In the page from “Teeth for the Iron Horse” shown above the discussion between Clay and Palomino in the first two panels is done in a manner that is very typical for Kirby. There seems to be a progression of art that looks the most like Kirby’s at the beginning of the story grading into work less typical for Jack. I usual take this as a sign that an artist was doing “in between” work. That is Kirby would supply a layout that would be tighter in the beginning and then getting rougher. In cases such as this I give joint credits. The inking, while still somewhat clumsy, is handled better then that found in “Fight To The Finish” (BR #4), “Last Mail To Red Fork” (BR #5), or “Bandits, Bullets And Wild Wild Women” (BR #5). The eyebrows still have the distinct Meskin angularity to them.

Boys’ Ranch #6 (August 1951) “Happy Boy Carries the Ball” page 2, art by Jack Kirby and unidentified artist

The page above from “Happy Boy Carries the Ball” has in my opinion a much more Kirby feel to it. This is particularly noticeable in gentleman in panel 5. The layout of the entire page is much more like Kirby’s then the other stories reviewed earlier. I suspect that as in “Teeth for the Iron Horse”, Kirby may have been supplying layouts that were tighter in some places then in others. I do have some reservations. The ending page of the story is really not done were well; it is not always clear what is happening. This would be very unusual for Jack as he was above all else an excellent graphic story teller. So either this work was edited with some panels removed, or the ending was not based on Kirby layouts. The original art for this story is still in Joe Simon’s collection. That is all but the last page and so cannot resolve this question. All and all, I think that joint credits should be used here as well even if I cannot say for certain who the second artist was.

Boys’ Ranch #2 (December 1950) illustration from “Jack McGregor’s Bluff”,

Boys’ Ranch #4 (April 1951) illustration from “Killer Stallion”, art for both by Jack Kirby (these illustrations were not included in Marvel’s reprint volume)

Even with the decline in the last three issues, Boys’ Ranch certainly was one of Simon and Kirby’s greatest creations. Stories were given enough length to fully develop. Some stories had themes that normally never showed up in comics. Pinups were used to an extent that would never be repeated by Simon and Kirby. With such great pinups, splashes and stories you can tell Joe and Jack gave Boys’ Ranch their all. It failed. There is no getting around it. No paper glut or a failing distributor can be used to explain it away. No matter how highly esteemed Boys’ Ranch may be today, it only lasted six issues. Having been given a year to catch on, apparently sales were too low to warrant its continuation. It was Simon and Kirby’s greatest failure.