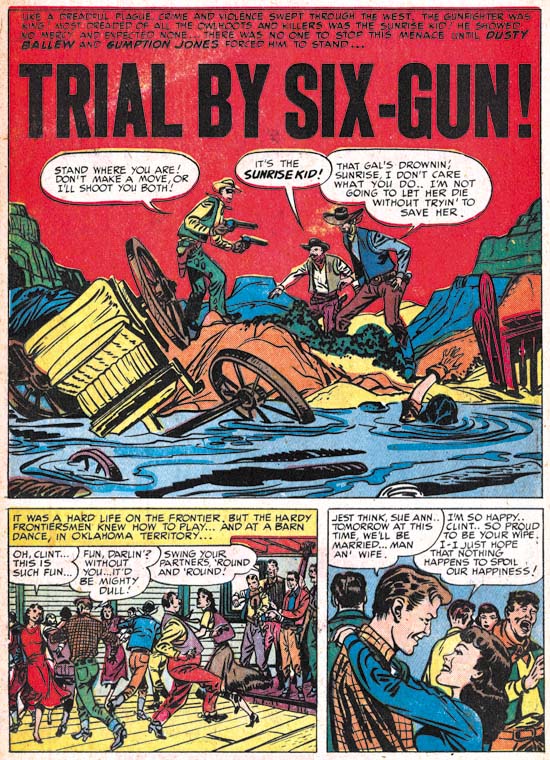

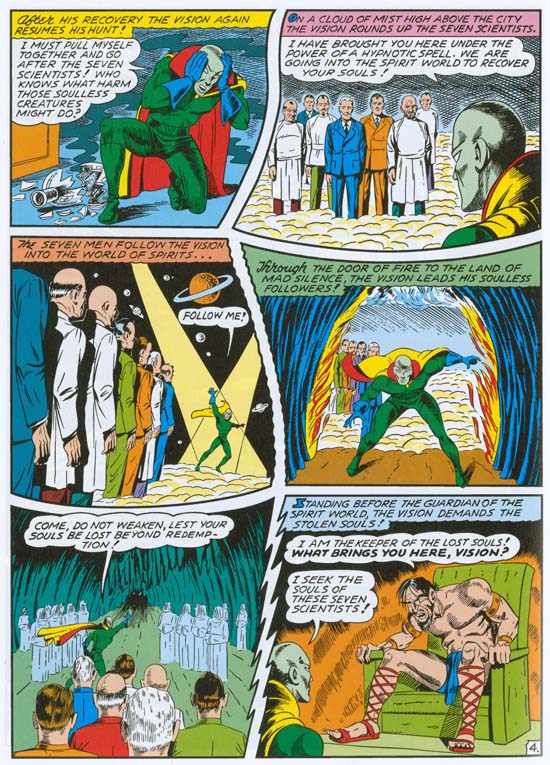

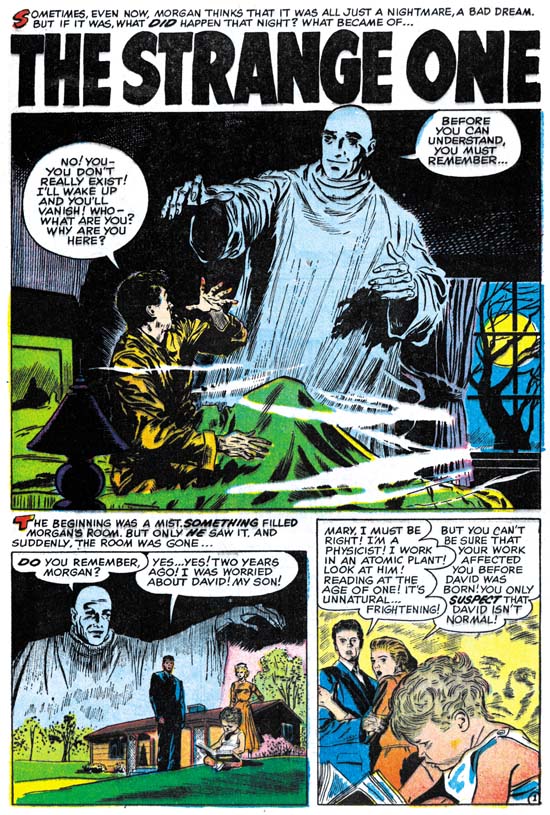

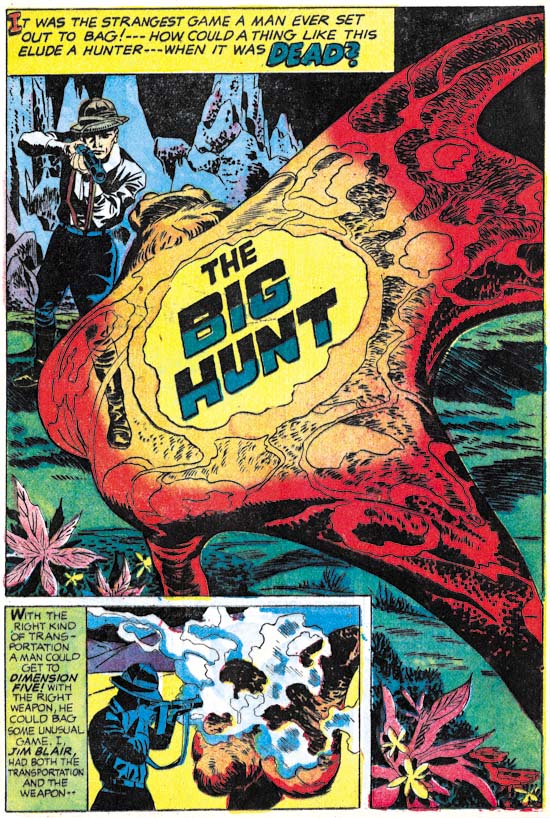

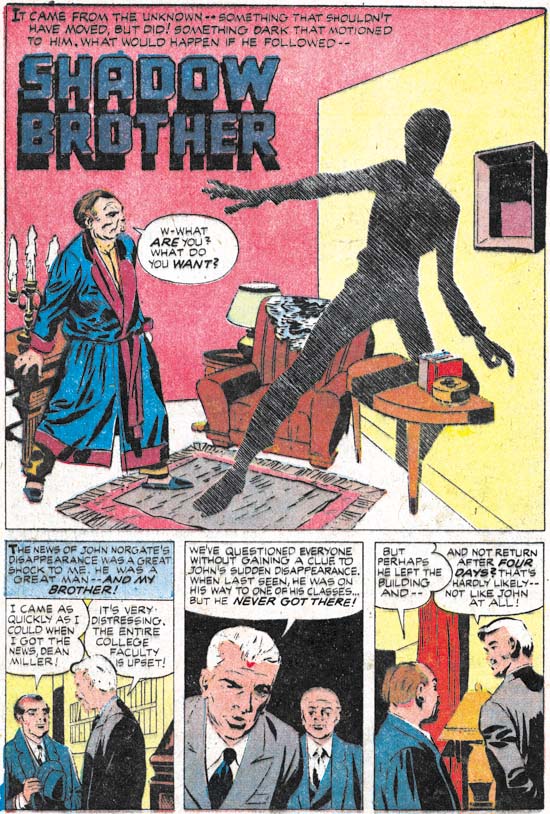

Race For The Moon #2 (September 1958) “The Face On Mars”, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Al Williamson

This is another group of pieces from the late Joe Simon’s collection. Joe was really fond of the inking that was done on these and other Kirby pencils from Race For The Moon and Blast-Off titles. I have discussed this work recently and why I believe it was inked by Al Williamson (Kirby Inkers, Al Williamson). In the interview Williamson gave for the Jack Kirby Collector #15 he says he did about four or five stories, although I think he may have done a little more than that. One of his statements from the interview:

TJKC: I was just reading some of those Race For The Moons. There’s some beautiful stuff there.

AL: Well, he did a beautiful job. Some of it was redrawn by somebody there, I guess because it didn’t pass the Comics Code or something. There’s parts that I didn’t ink, because it’s not my drawing or Jack’s drawing. Somebody went over it and changed some things, like a monster or something to make it more pleasing to the eye, which bothered the hell outta me. I never really thought I did him justice, though. The drawing is there, because it’s Jack Kirby’s drawing, but I just traced what he penciled.

Once again I have to disagree with Williamson. I have examined all the original art in question with the exception of one story (“The Long, Long Years” from RFTM #3) and none of the art has been altered, at least not after inking. And Williamson is wrong about having “just traced what he penciled”. It is true that Williamson followed Kirby’s pencils very accurately and I am sure Jack’s pencils were very tight. But the spotting was all Williamson’s. Not that I believe Al ignored Jack’s directions. It was Kirby’s practice at that time to just provide the outlines indicate everything else with simple lines. The rest was up to the inker to provide and in the case of Williamson’s inking with spectacular results.

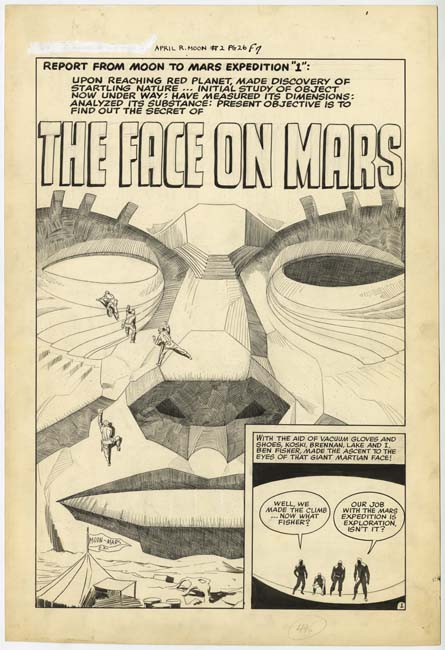

Race For The Moon #2 (September 1958) “The Face On Mars”, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Al Williamson

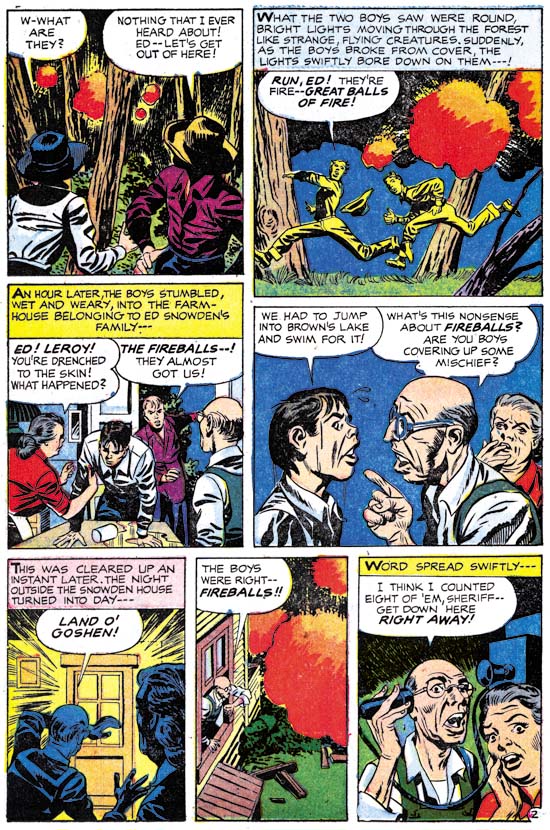

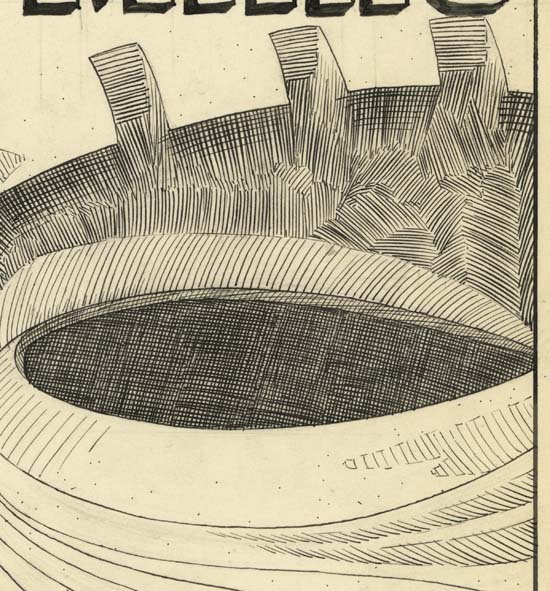

The inking is detailed but not at all dry. A lot of it was done using a pen, in fact the splash panel was done almost entirely in pen. The low resolution image of the art that I provide just cannot give it justice. So above I also give a close-up to show the care taken in the pen work. Perhaps the reader noticed the small ink dots scattered around the image. It is not unusual to find small ink drops on original comic book art although usually not as densely as here. So the reader could be forgiven if they assumed that was what was happening here. However these dots are all the same size and are not found either in the gutters between the panels or inside areas of crosshatching. The dots are another example of the care Williamson took in inking Kirby’s pencils. This work was done early in Al’s career but by this time he certainly should have been aware of the limitations of the primitive printing that was used in the publication of comic books of his day. Williamson knew, or should have known, that much of his efforts would be lost in the final published results.

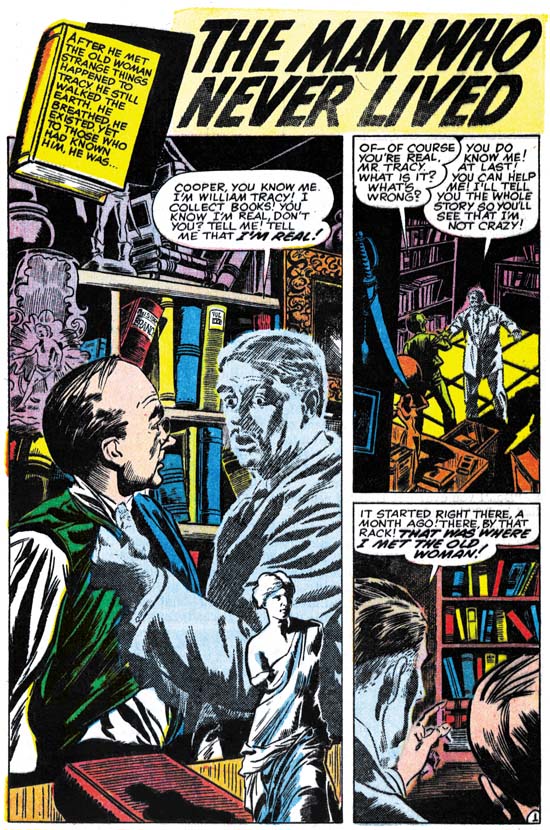

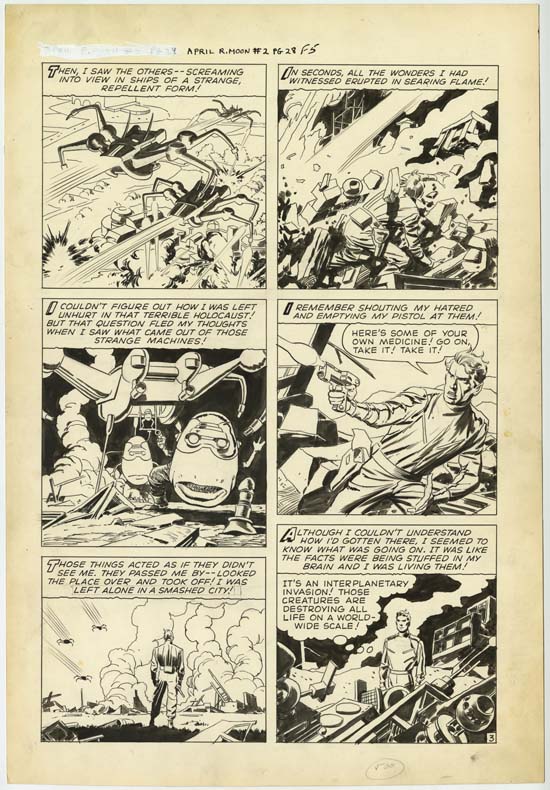

Race For The Moon #2 (September 1958) “The Face On Mars” page 3, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Al Williamson

Pen was used for the inking throughout the story but unlike the splash panel the pen work was augmented with much user of the brush. Clearly Williamson was as proficient with the brush as he was with the pen. The inking is precise and flawless but nonetheless retains a fresh and lively quality. There is no use of white-out or any other corrective measures on any of the pages of this story. That is except for the white-out applied to page identification in the upper left corner on all the pages. Apparently there was second thoughts about what comic book this work would actually appear in. It is possible to read through the white-out and surprisingly the original use was identical to the final use right down to the page number.

An “F5” has been added to the page identification by another hand. This is the flat number that the page belongs to. Comic books were printed on four sheets of paper with four art pages on each side of the sheet. After printing the sheets would be folded and trimmed. Because of this process the sheet was not organized in a simple sequential order and the flat number added was an aid to insure the art was placed on the proper sheet. Another notation from the production process is the pencil number 500 found at the bottom of the page. This was an instruction to reduce the art size to exactly one half. The splash page had the number 496 for a reduction that was close but not exactly one half. It has been years since I last used a stat camera but I believe that this would indicate a slightly greater reduction in size than the other pages.

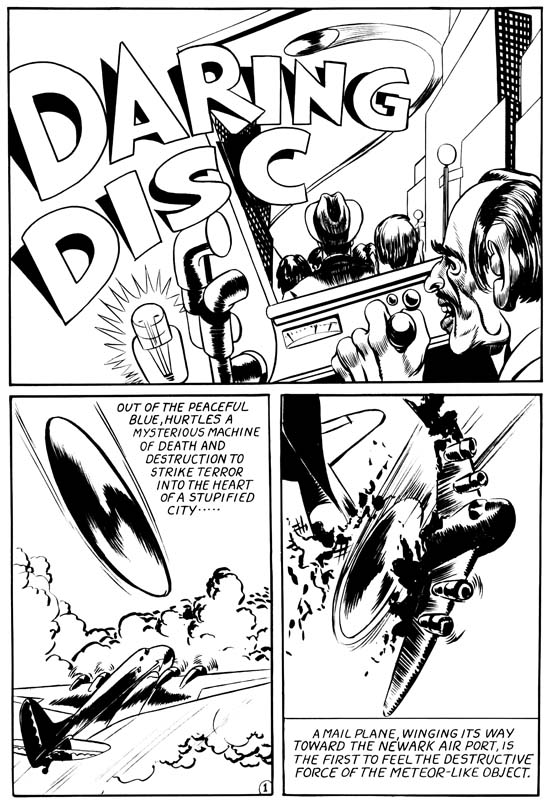

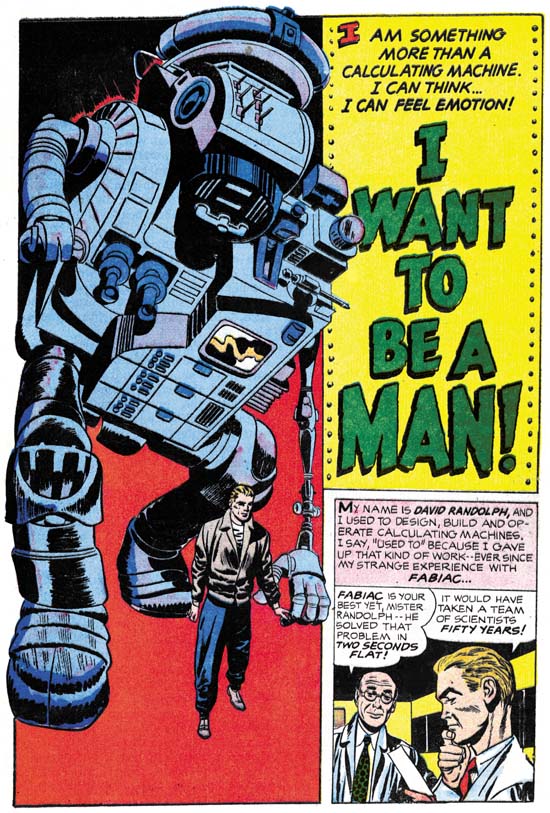

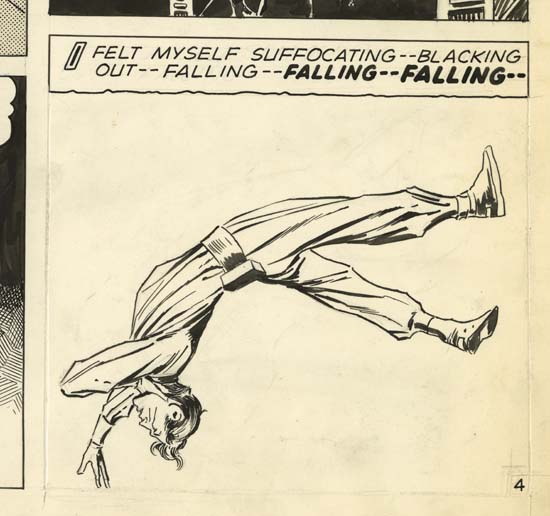

Race For The Moon #2 (September 1958) “The Face On Mars” panel 6 page 4, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Al Williamson

Williamson liked to leave out the panel borders for some of the art. Apparently the art was already lettered with panel borders before the art reached him for inking. Not a problem because it was two ply paper, that is there was another usable surface right below the original one. So Williamson was able to use a razor to carefully cut along side the panel borders and then peal them off. Although faint, the reader should be able to see the cut marks on the close up above.

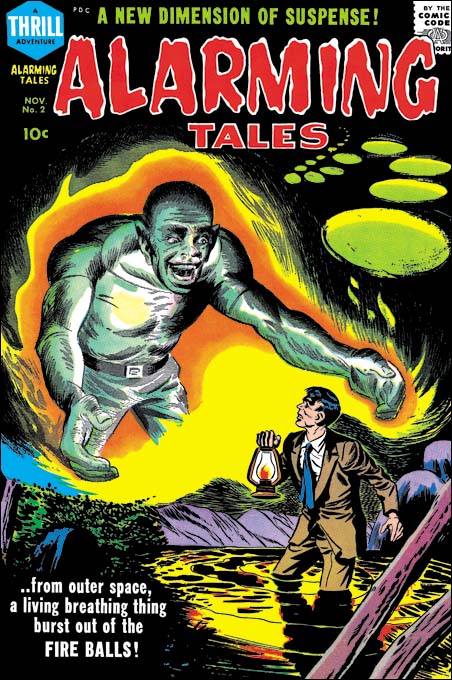

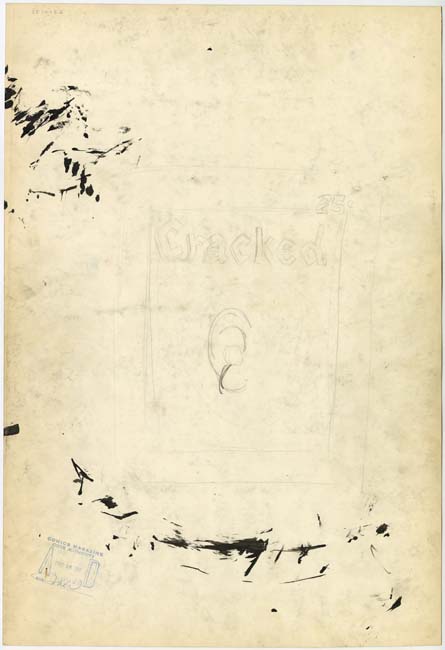

Race For The Moon #2 (September 1958) “The Face On Mars” back of the original art for page 5

The back of much of the art used in Race For The Moon and Blast-Off was used by the inker to prepare his brush. Or at least that is what I interpret the streaky inking such as seen on the back of page 5 shown above. A similar marking, although much less extensive, was found on the back of one of the pages of a Fly story that Williamson drew about a year later (Speaking of Art, Al Williamson’s Fly). With one exception such markings only appear on the back of pages that I believe were inked by Williamson.

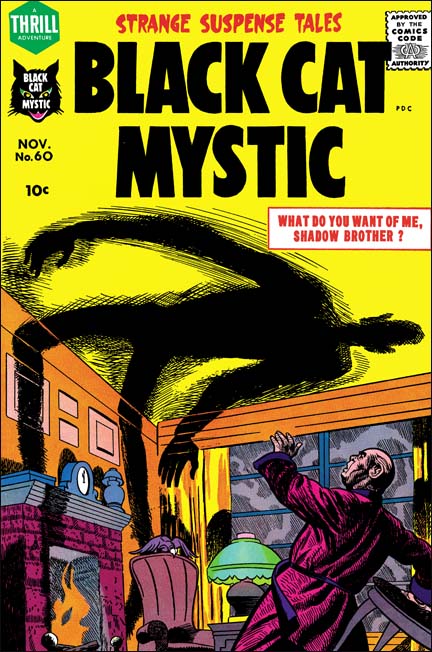

The Comic Code Authority approval stamp is dated December 18, 1957. The approval stamp was only applied to finished art ready for publication which means that date was the latest the original art could have been created. Normally the work would be published shortly later. Cover dates are not the date of publication, but rather the date the comic could be removed from the racks. The approval date for Williamson’s work for Adventure of the Fly #2 was a short three months earlier than the cover date. Art for Race For The Moon #1 was approved about four and a half months before the cover date. But for “The Face On Mars” the approval stamp is dated October 24, 1957, over nine months before the cover date. I do not claim that everything by Simon and Kirby could have been a financial success but Harvey’s habit of holding up publication of some of their work did not help.

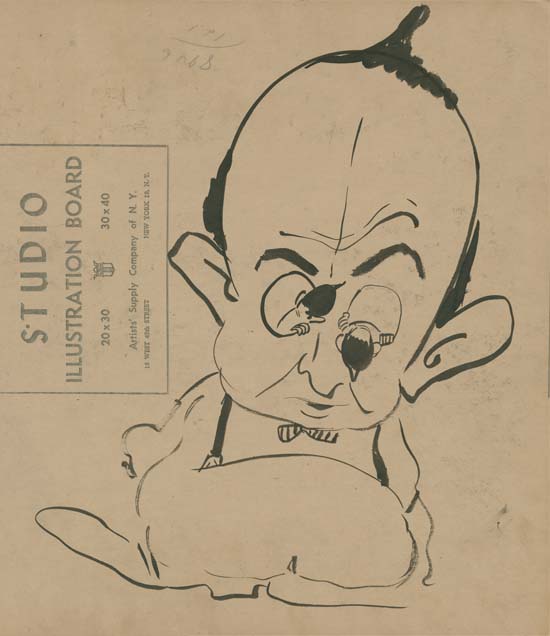

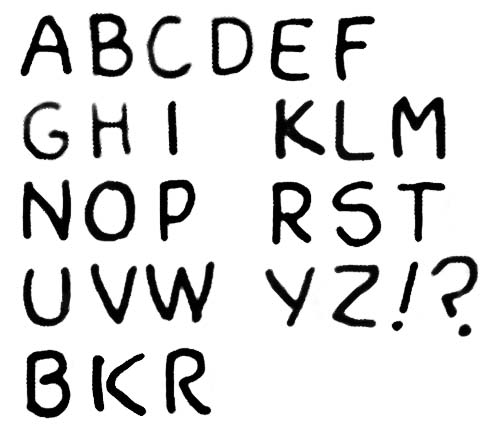

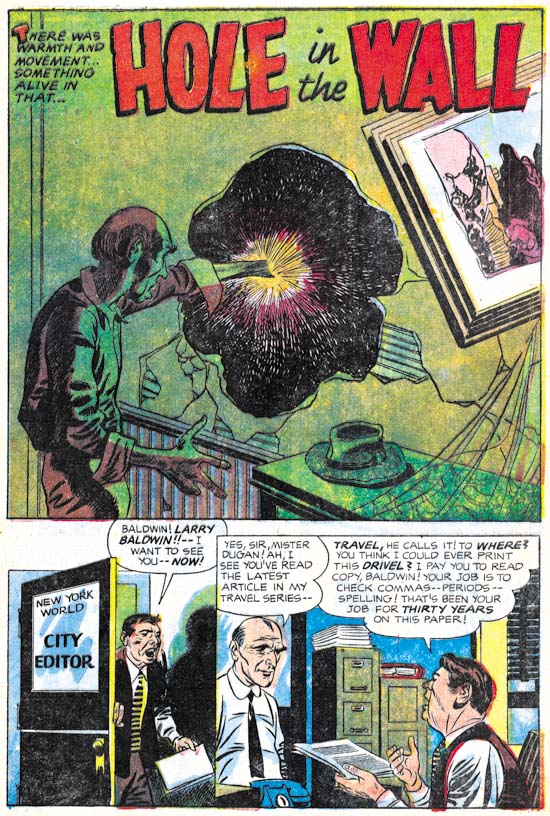

Race For The Moon #2 (September 1958) “The Face On Mars” close-up of the back of the original art for page 5

The back of page 5 also has a pencil sketch. I provide a close-up above that has been adjusted in Photoshop to provide greater contrast. Cracked was a clone of the popular Mad magazine. Mad had a lot of copy-cats but only two had any real success, Cracked and Sick. The double border in the sketch matches design of the early issues of Cracked. The logo in the sketch matches the one found on issues #1 to #9 (March 1958 to May 1959). I have no idea what the image is supposed to represent but it does not match any found on the nine initial published issues. But an even bigger mystery is why there should be a sketch of a Cracked layout at all. As far as I know none of the parties involved in the creation of this piece (Jack Kirby, Al Williamson and Joe Simon) had any relationship to Cracked magazine.