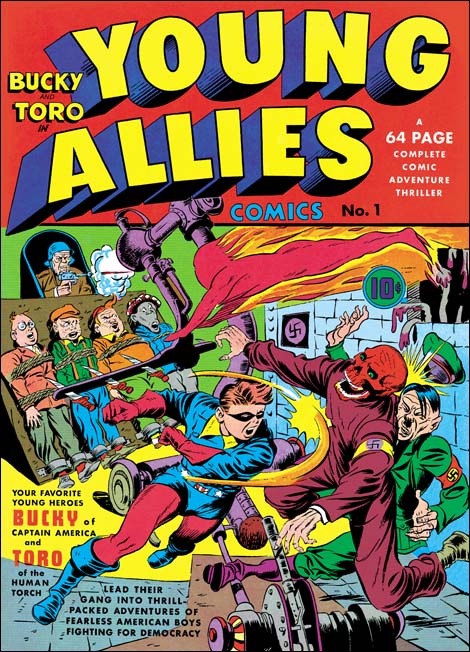

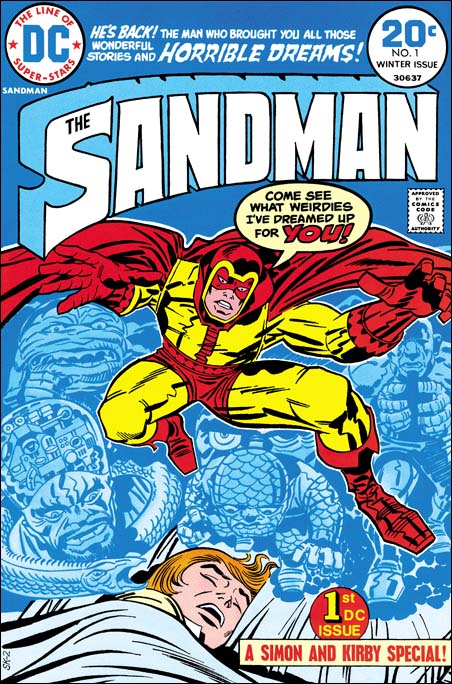

Sometime ago I posted about the artists that replaced Joe Simon and Jack Kirby during the period that both were performing military service. (Replacing Simon and Kirby, Chapter 1, Chapter 2 and Chapter 3). My previous postings concerned the Newsboy Legion but here I am going to discuss Sandman. Unfortunately the reader will be at a greater disadvantage compared to previous chapters. While DC’s Newsboy Legion archives included work done by other artists, the Simon and Kirby Sandman Archive was limited to just Joe and Jack (at least that was DC’s intention).

To refresh the reader’s memory, while working for DC Joe and Jack realized that they would soon have to leave to perform their military duty. So they worked hard at creating an inventory that could be used while they were gone. Simon and Kirby were able to provide quite a bit of inventory but eventually it ran out.

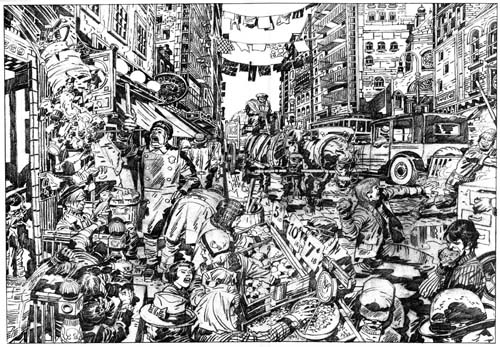

Adventure #91 (April 1944) “Courage a la Carte”, pencils by Jack Kirby

The Sandman covers and adventures that appeared before issue #91 were done by Simon and Kirby. While the splash for “Courage a la Carte” was not Joe and Jack’s finest job, I am confident that Kirby did the pencils. The most obvious give-a-way is the thug at on the right of the splash. I have no idea who the inker was but obviously it was neither Joe nor Jack. Like I said this was not their finest effort but their inventoried work often was not quite as nice as their less rushed efforts.

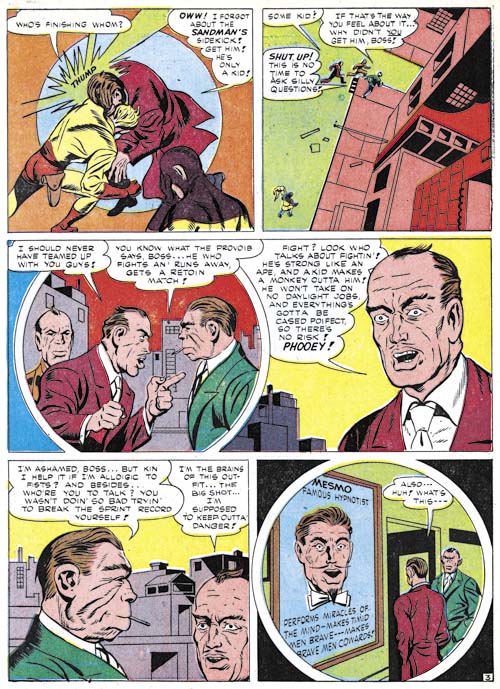

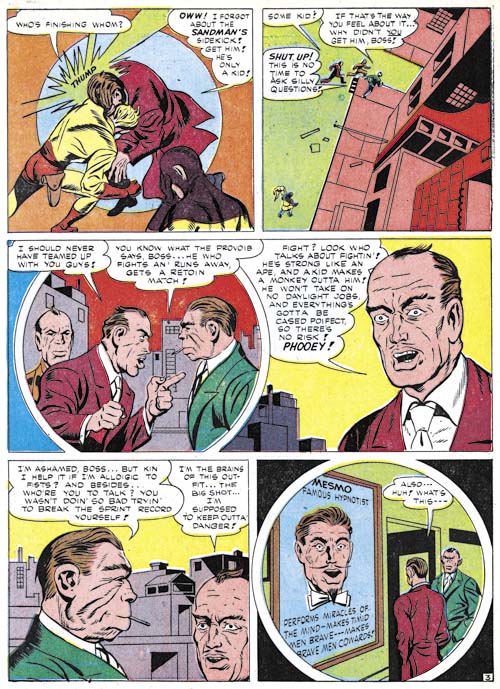

Adventure #91 (April 1944) “Courage a la Carte” page 3, pencils by Gil Kane?

But what followed the splash to “Courage a la Carte” looks pretty crude, much cruder than would be expected even for the inventory work. For good reason because it was not penciled by either Jack or Joe. Kane would have been very young at the time and even he admitted that his efforts at the time were rather poor. The attribution of this art to Gil Kane is not based on the art itself, instead I base this attribution on a statement that Gil made

I got a “Newsboy Legion” job to do by myself (like I had done the rest of them except they didn’t fix it up or do the splash),

So far “Courage a la Carte” and “The Lady of Linden Lane” (Star Spangled #30, March 1944) are the only stories for DC that I have seen with a Kirby splash for a story otherwise done by another artist (although I have not studied the Boy Commandos stories yet). Since the circumstances matches Gil’s remarks, I have tentatively credit him for these pieces. The two Kane stories were published at about the same time (while I use March as the cover date for Adventure #91, that title was actually a bimonthly) but were likely to have been done earlier and inventoried like the rest of Simon and Kirby’s work.

Unlike most of the Sandman art that I cover in this chapter, “Courage a la Carte” was one of the stories included in DC’s Simon and Kirby Sandman Archives. It is also listed in the Jack Kirby Checklist. But as I said above, Kirby only drew the splash.

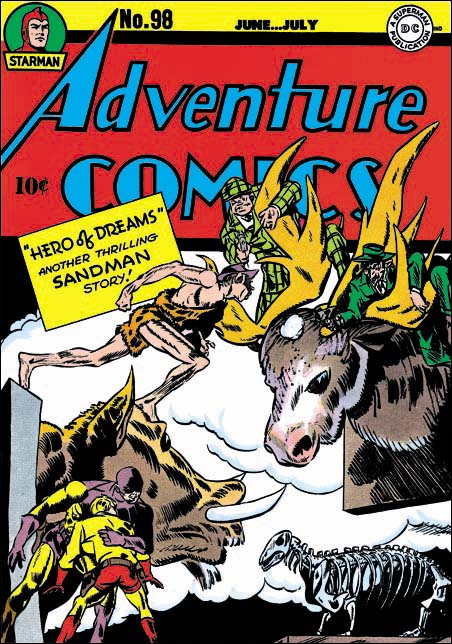

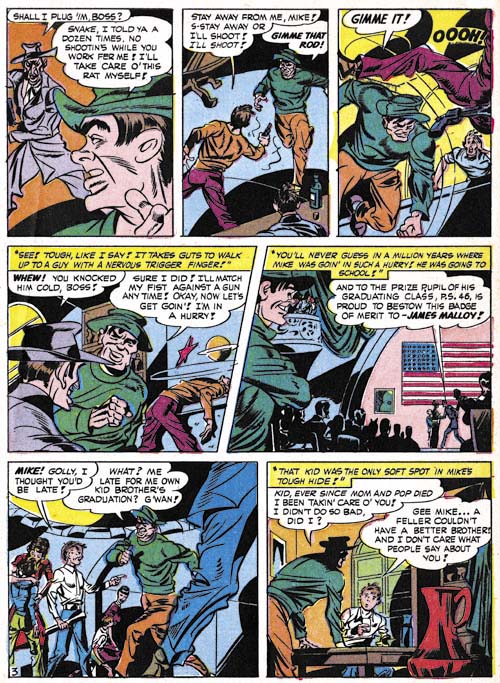

Adventure #92 (June 1944) “Tough Guy” page 3, pencils by unidentified artist

After Kane, work on Sandman was done by another artist, the same one who followed Gil on the Newsboy Legion. Earlier I had misidentified this artist as Kane but the timeline simply will not support that. Kane entered military service in April or May 1944 but work by this artist appeared until October 1945. Joe Simon suggested that this might be the Cazeneuve brothers, but I have seen enough of their work to discount them. Other suggestions have been made but I have not found them convincing either.

The work by this artist is nothing like that for Simon and Kirby but it would be a mistake to discount him. I find his art to be interesting and original. The quality varies from story to story but I have now come to believe that much of that was due to the various inkers used on his pencils.

Adventure #94 (October 1944) “Reincarnation of a Rogue”, pencils by unidentified artist

The same replacement artists discussed above worked on a number of Sandman stories. The stories were still credited to Simon and Kirby but were any of their fans really fooled? I really enjoy much of his story art but find most of his splashes not all that interesting. I include above one of the better examples of his splashes.

Adventure #95 (December 1944) “The Riddle of the Rembrandt”, pencils by unidentified artist

The main replacement for Simon and Kirby had an uninterrupted run for the Newsboy Legion (Star Spangled #31 to #49, April 1944 to October 1945). But he only did three issues of the bimonthly Sandman (Adventure #92 to #94, June to October 1944) before another artist was used. Like most of the replacement artists, I really have no idea who did “The Riddle of the Rembrandt” but his talent is pretty obvious.

Adventure #97 (April 1945) “No Curtains for Cupid”, pencils by unidentified artist

The main replacement Simon and Kirby replacement returned after a single issue absence. “No Curtains for Cupid” looks rather different from the other examples I provided above. I still feel they were done by the same penciler but in my opinion much of the apparent differences can be assigned to the wide range of inkers used. Regardless of the inker, the art retains a unique style.

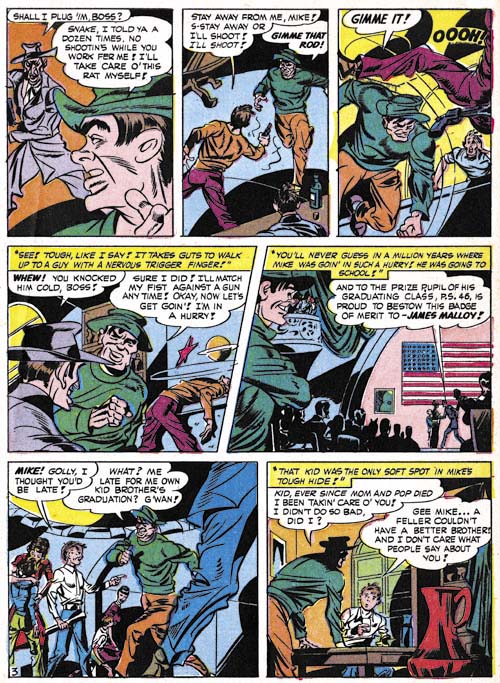

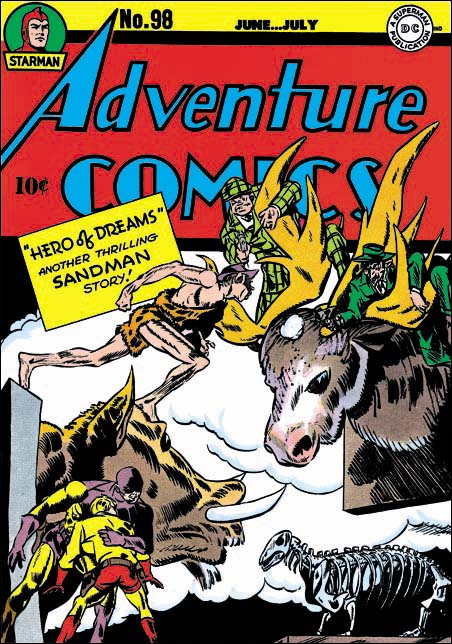

Adventure #98 (June 1945), pencils by unidentified artist

The cover to Adventure #98 was previously discussed on this blog (Not Kirby, Adventure #98). In that post I recounted a number of reasons why I felt the cover was not done by Jack Kirby but the most important of them was the manner that the caveman’s right forearm was drawn. Kirby’s anatomy was not accurate but he always made kept a solid underlying form. The form of the caveman’s forearm is broken in a manner that Jack never did. To all the reasons I previously presented I can now add another. a mirror image of the caveman figure (in more modern clothing) is also found twice on the cover of Star Spangled #45 (June 1945, Replacing Simon and Kirby, Chapter 2). This is much too much use of the same image to credit to Jack. Swiping is a much more obvious explanation.

The main replacement artist would also provide the work for Adventure #99. This means with the exception of a single issue (Adventure #95) the main replacement artist would draw Adventure #92 to #99; June 1944 to August 1945. This matches pretty well with his uninterrupted run for the Newsboy Legion.

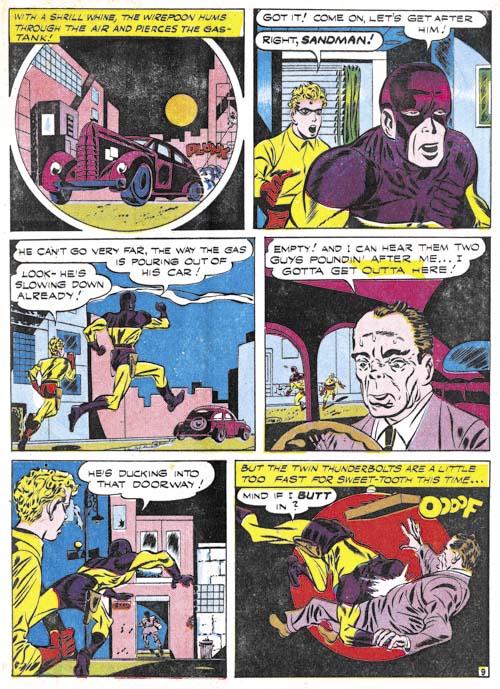

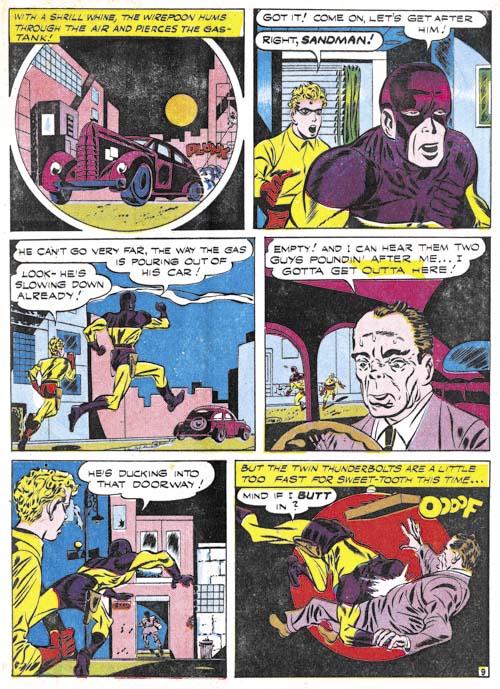

Adventure #100 (October 1945) “Sweets For Swag” page 9, pencils by unidentified artist

Jack Kirby returns to Adventure Comics with issue #100. However Kirby only provided the cover while the interior Sandman story was done by a rather inferior penciler. The primitive art for “Sweets for Swag” remind me of the work that I am now attributing to Gil Kane. In fact the main replacement artist run for the Newsboy Legion was also followed by what looks like the same artist in Star Spangled #52 (January 1946, Chapter 2). In Chapter 2 I had questionably credited it to Gil Kane but I am having second thoughts. Gil would have been entering the armed forces at the time this art was created so it seem unlikely he would have drawn it. This story is another one that was mistakenly attributed to Kirby in the DC Simon and Kirby Sandman Archives and the Jack Kirby Checklist.

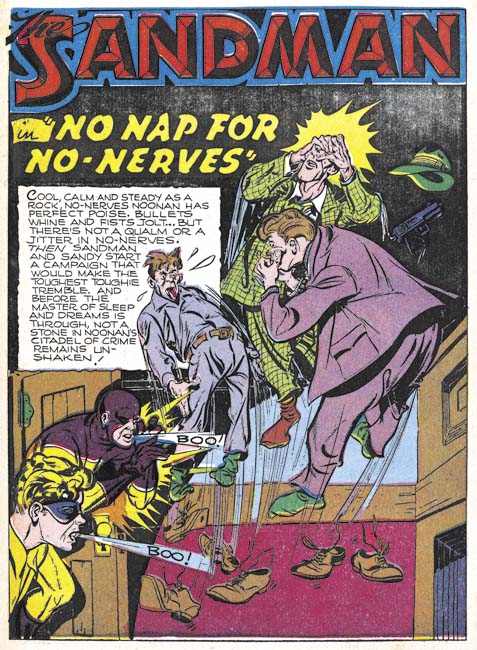

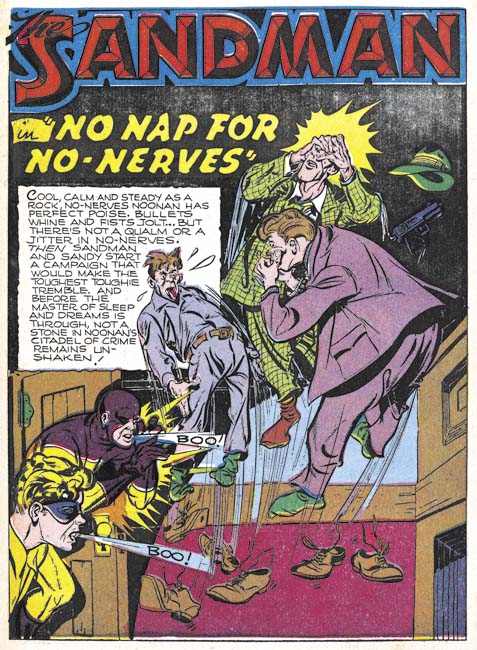

Adventure #101 (December 1945) “No Nap for No-Nerves”, pencils by unidentified artist

Once again Kirby provides a cover for Adventure #101 (December 1945) but did not draw the interior story. The artist who did do “No Nap for No-Nerves” did a good job although I got to say that in his splash Sandy and the Sandman appear to be blowing the thugs away and not scaring them out of their shoes.

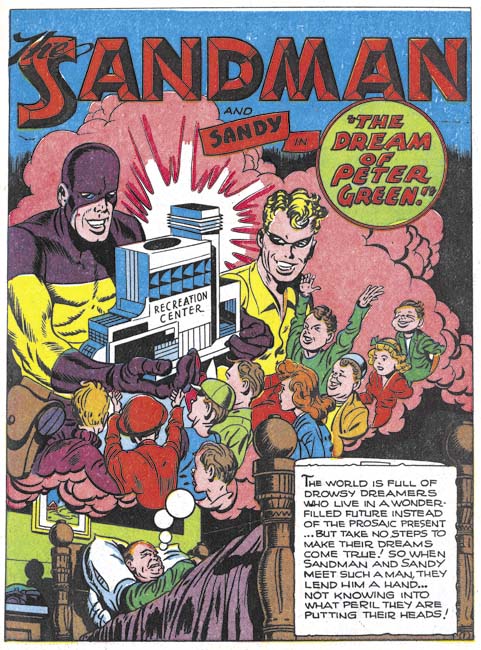

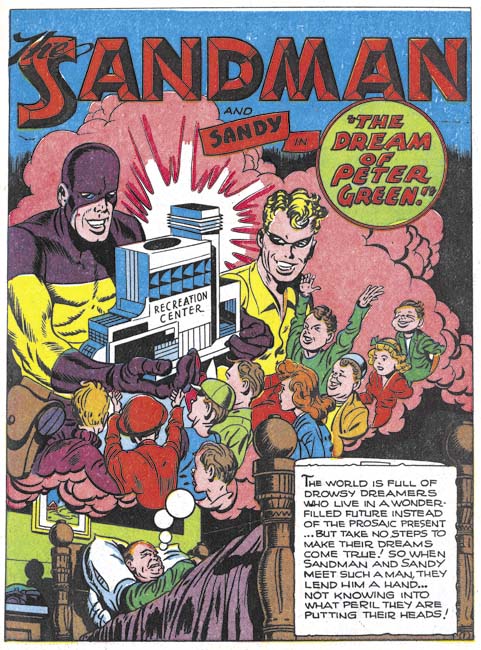

Adventure #102 (February 1946) “The Dream Of Peter Green”, pencils by Jack Kirby

With Adventure #102 Kirby is finally back to drawing both the cover and the story art. Sandman was back in safe hands and all was once again good with the world. Or that would have been the case if this was not the last Adventure issue to include the Sandman and Sandy. Yes the Sandman was replaced with Superboy and Kirby would not appear in the title again until 1958 when, without Simon, he drew Green Arrow. A convenient explanation for the sudden demise of Sandman so shortly after Kirby’s return would by that it was a reprisal to Simon and Kirby going to a competitor, Harvey Comics, to publish their Stuntman and Boy Explorers. While that would make an interesting story the timing just does not work. While Adventure #103 and Stuntman #1 would both come out in April, DC would have to have made the decision to change directions with Adventure before they were likely to have found out about Simon and Kirby’s defection.

While Simon and Kirby were away, the two titles followed a similar timeline.

- March/April 1944 – Kirby drawn splash, rest of story by Gil Kane?

- April/June 1944 – First story by the main replacement artist

- June 1945 – First cover by the main replacement artist

- August 1945 – Last story by the main replacement artist

- September/October 1945 – First cover by the returned Kirby

- February 1946 – First story by the returned Kirby

There remains one other feature to be considered, the Boy Commandos.