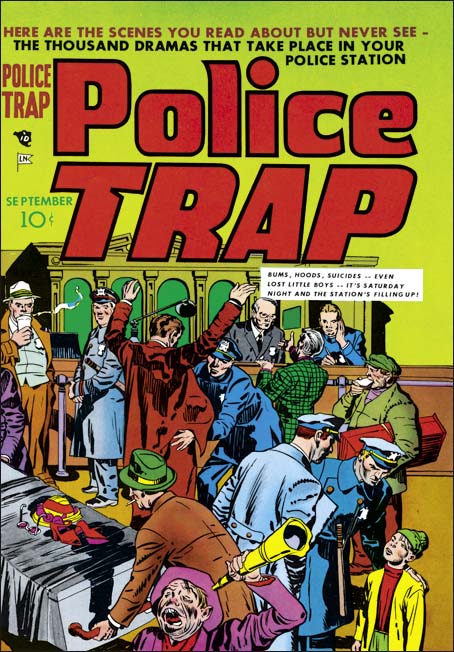

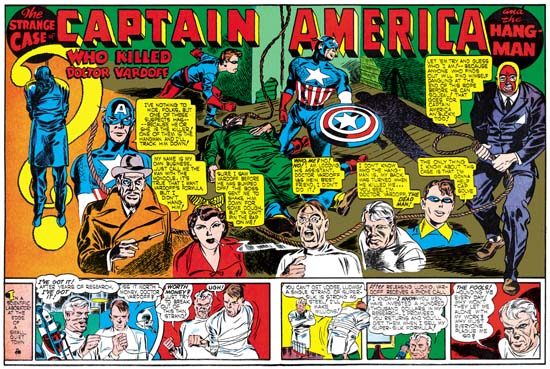

Police Trap #2 (November 1954), pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

A cover similar in concept to that used for the first issue. This time the muster room is portrayed:

This is where the officers relax, unbutton their jackets, have their shoes shined, smoke, bull session, rough-house, write reports, and just ease up after a hard day on the beat…

But would we really expect a muster room to have a shoe shine stand or a drunk sleeping it off? But perhaps the most unusual feature of this cover is one easy to overlook. Look carefully at the third policeman from our left, he is African American. Race did not play an important part of Simon and Kirby productions. When other races were depicted, most often it was Asians but otherwise Simon and Kirby comics were almost uniformly populated by whites. African Americans were generally invisible as they were in many popular media of the day. One glaring exception was Whitewash from the Young Allies a Simon and Kirby creation for Timely Comics. However stereotypical and (to modern eyes) objectionable characters like Whitewash were not part of Simon and Kirby productions that preceded or followed Young Allies. Further Whitewash seems to be delegated small rolls in the splashes from Young Allies that were actually drawn by Jack Kirby (Young Allies and the L Word). This suggests that the presence of Whitewash in Young Allies was not due to Simon and Kirby idea but dictated by someone else. As for the Police Trap #2 cover it is not at all obvious that the policeman was drawn by Jack Kirby as an African American but rather it was the colorist who made him so. Unlike their other comics where the coloring was the responsibility of the publisher, Simon and Kirby were the actual publisher of Police Trap and therefore they were responsible at some level for the coloring. I do not know if Joe or Jack actually colored this cover but minimally they assigned the colorist and approved the results.

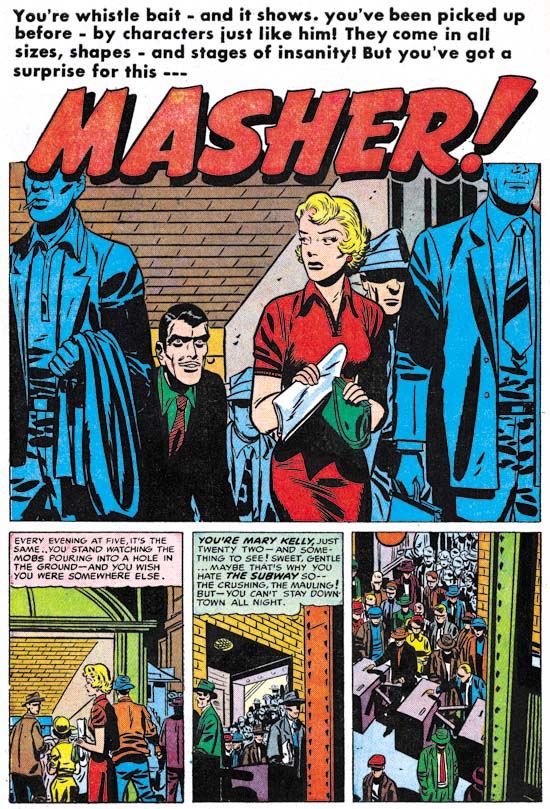

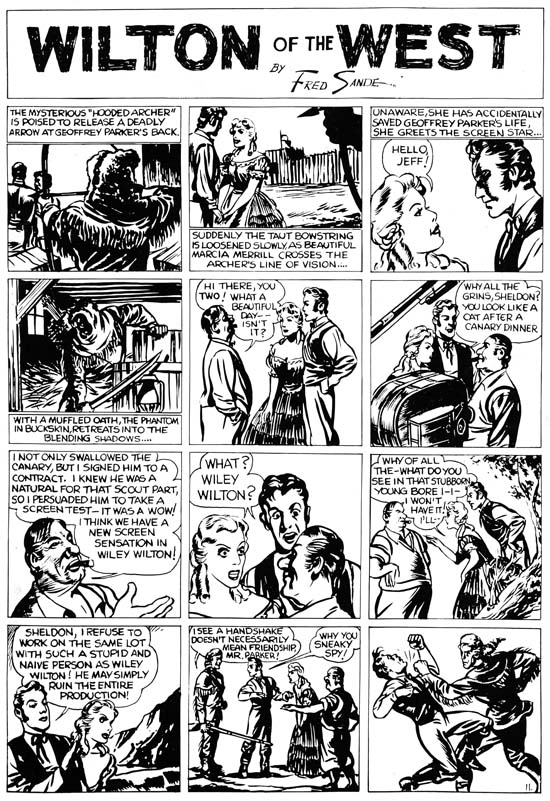

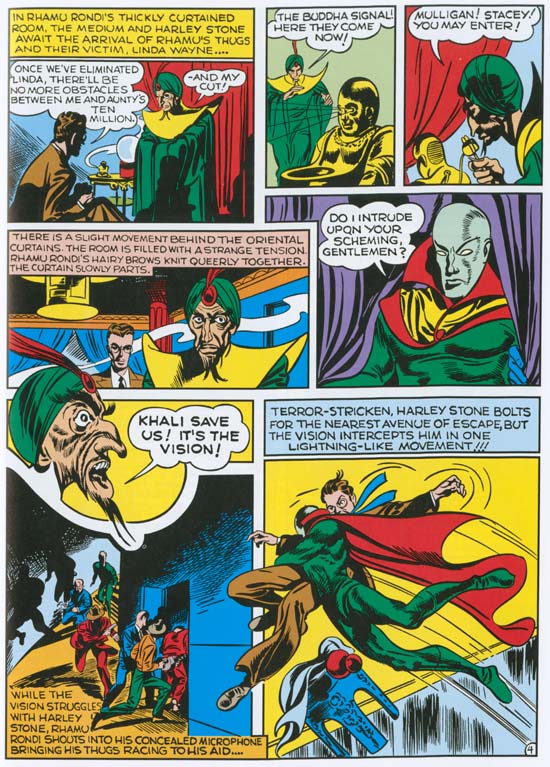

Police Trap #2 (November 1954) “The Hoodlum”, pencils and inks by John Prentice

“Usual suspects” Bill Draut and Mort Meskin are absent from the second issue of Police Trap but it does contain the third of the regular Simon and Kirby artists, John Prentice. John does his typical excellent job on the art. Perhaps my only criticism is that he has made the two policemen too similar in appearance. At times I find it difficult to determine who is being represented as for example the last panel of this page.

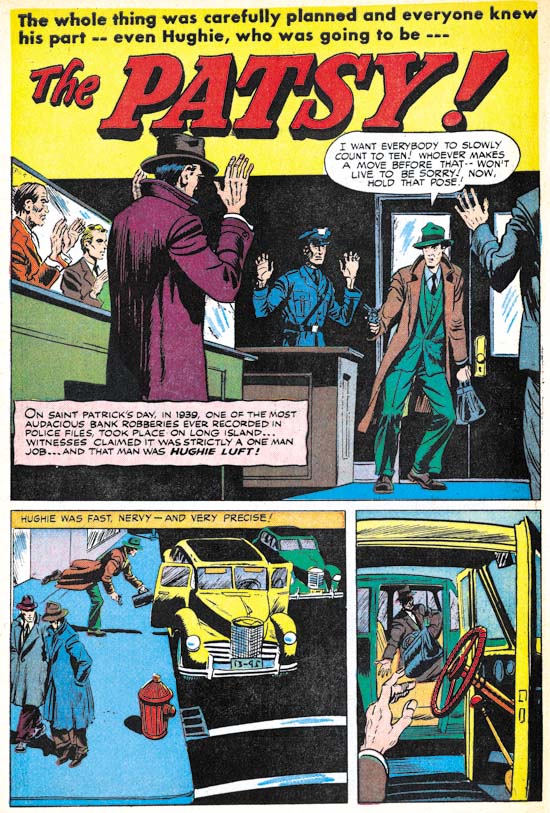

Police Trap #2 (November 1954) “The Patsy”, art by unidentified artist

In the past I have never come up with even a guess on who did the art for “The Patsy”. But on reviewing it now I find parts, just parts, that remind me of Bob McCarty. For instance the man on the extreme left of the splash panel. But there are other parts that seem so untypical for McCarty such as the unusual perspectives found the last two panels on the same page. I am unable to make sense of this combination of aspects that look like McCarty and those that do not so I continue to leave the attribution as unidentified.

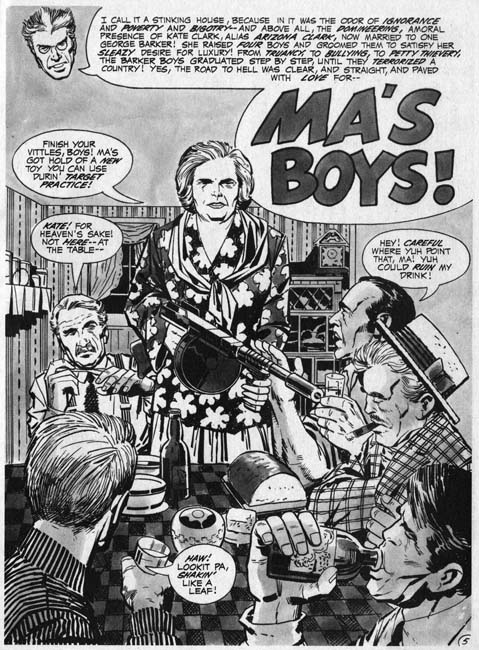

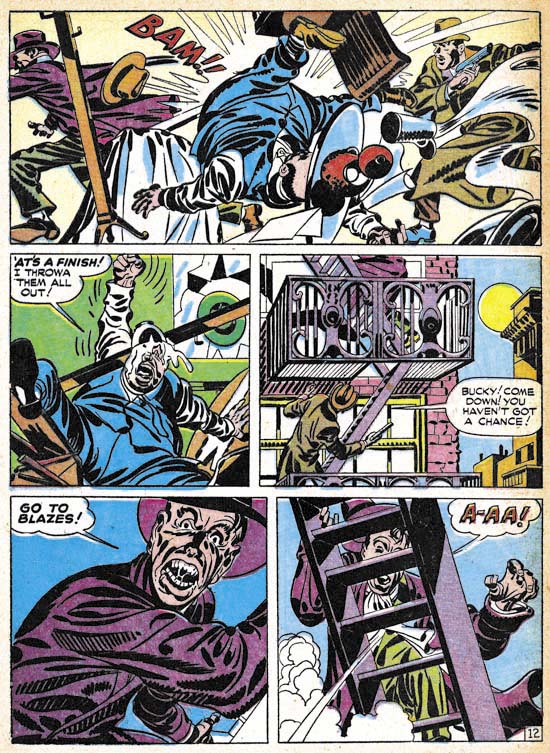

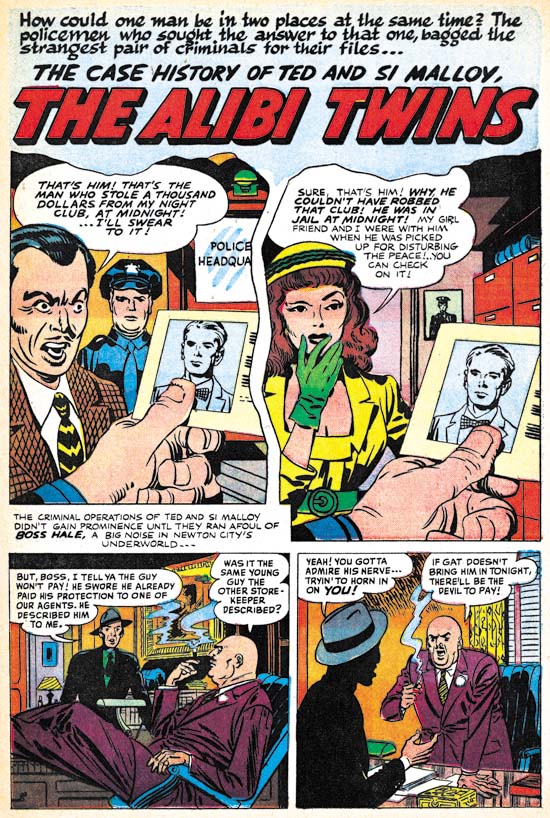

Police Trap #2 (November 1954) “The Alibi Twins”, two panel splash penciled and inks by Jack Kirby, rest of the story by unidentified artist

Except for the covers and one pinup, Jack Kirby did not supply much art for Police Trap until the latter issues. But obviously Jack was still playing his normal roll as untitled art director. Here Kirby provides the first two panels, effectively combining to form a splash, for a story otherwise executed by another unidentified artist. While the vast majority of the stories in Simon and Kirby productions were completely drawn by one artist, it was not that unusual for Kirby to provide the splash either.

The story artist is another of those that appeared only briefly in Simon and Kirby productions of this period. Note the rather bizarre inking in the last panel. The man is completely blacked out except for the hat and his hands. This story is a little longer (9 pages) than most found in Police Trap which were usually 4 to 6 pages long. Further the focus of the story is on the criminal, not the police as was normally the case for this title. Add the unusual lettering in some places (in particular the use of a script for the first letter of captions) and this suggests that the piece may not have been commissioned by Simon and Kirby but instead picked up from some failing comic book publisher.

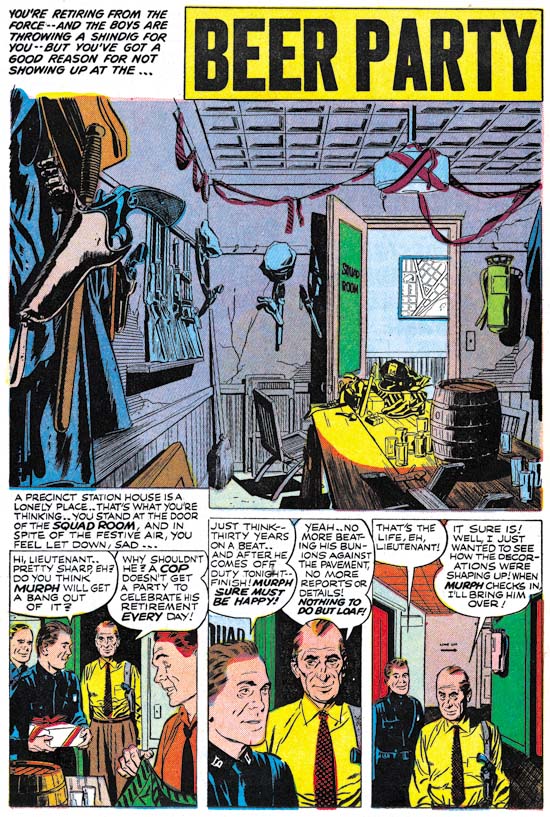

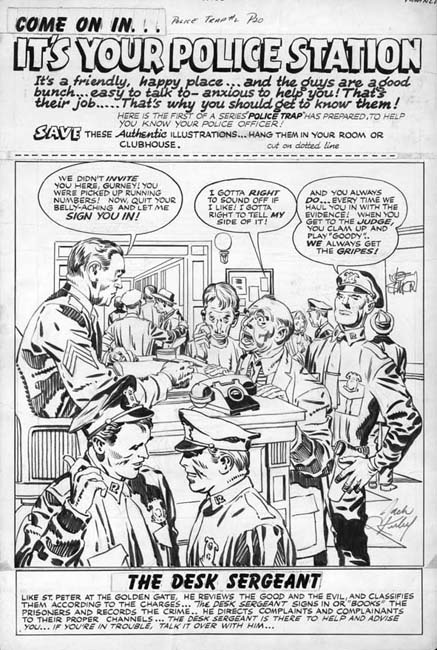

Police Trap #2 (November 1954) “Desk Sergeant”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

I have recently discussed “Desk Sergeant” (The Police Trap Pinup) so will skip commenting on it here.

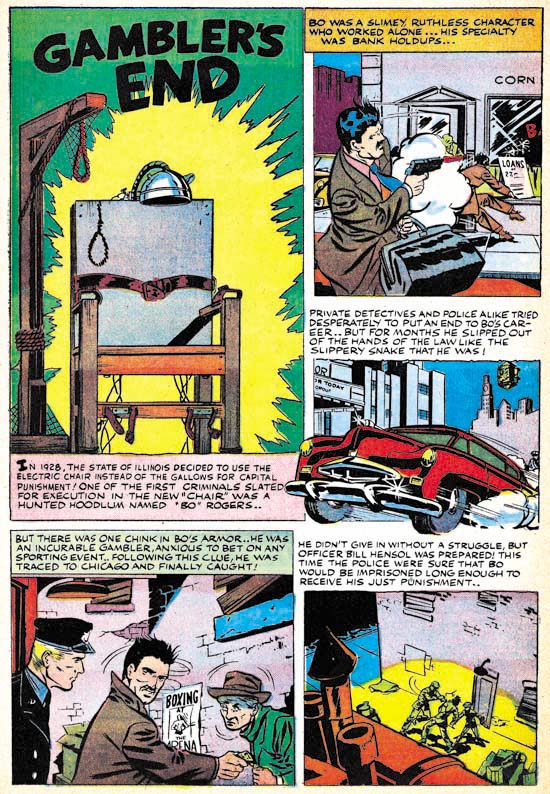

Police Trap #2 (November 1954) “Gambler’s End”, art by unidentified artist

A short two page piece by an unidentified artist. Unusual use of the first letter of some of the captions (for instance the bold ‘I’ in the splash caption) suggests that this story may also have been picked up from some failed comic book publisher.

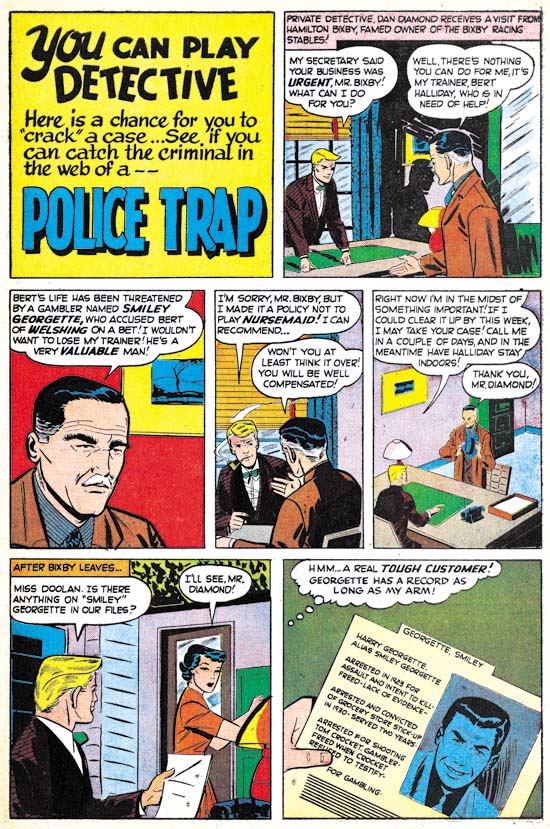

Police Trap #2 (November 1954) “Police Trap”, art by unidentified artist

Another short two page piece by an unidentified artist. A lot of talking heads. A better artist might have been able to carry it off but this one is too stiff and the result is a rather uninteresting story. I have detected nothing unusual about the lettering so this piece might have been commissioned by Simon and Kirby.

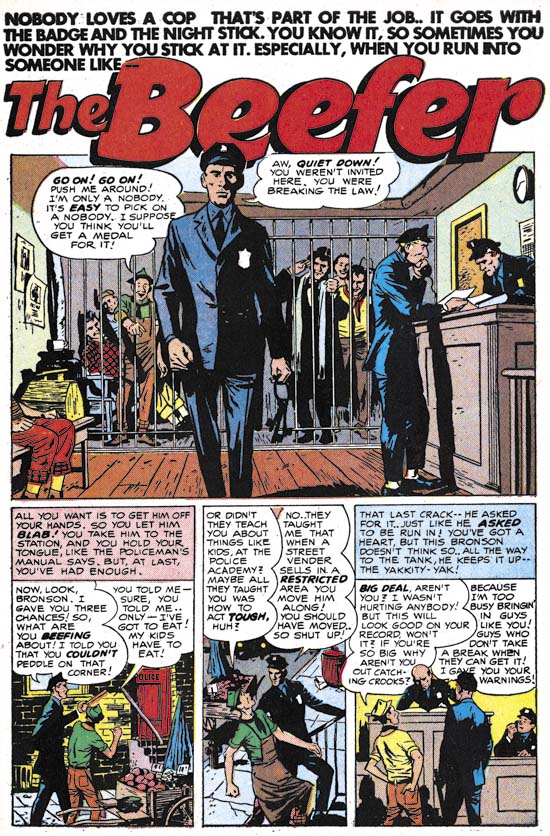

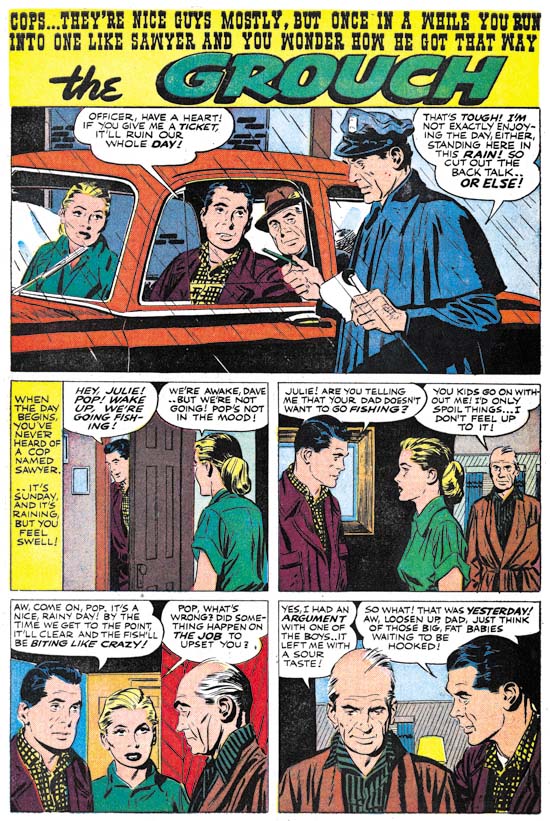

Police Trap #2 (November 1954) “The Grouch”, pencils and inks by John Prentice

Prentice opens and closes this issue of Police Trap. Actually he is the artist who really carries this issue what with a rather minimal contribution by Jack Kirby and none by Bill Draut or Mort Meskin. All the other artists are just nothing more than adequate. So in effect Prentice pretty much carries this issue.