I recently posted on the “Artist Loves Model” story from In Love #3 (December 1954). I appended a note to my blog entry where I admitted forgetting about a post by Bob on the Jack Kirby Weblog about the syndicated strip version of the story. Recently I received a copy of Buried Treasures v1 #2 which includes strips of this syndicate strip proposal. I have compared, panel by panel, the strips to the comic book story. I wrote out all the difference as an aid to my understanding what was done. Just in case anyone wants a blow by blow description I have posted the details. Here I will summarize what was done to convert the syndication strips into the comic book story.

The strips opens with Mayor La Flower. We will never see again, he is just one of Cobb’s fans reading his “Old Man Spry” to his juvenile radio audience. This beginning leaves little doubt that there were no earlier strips. The strips end abruptly with Inky going off to confront Donna Dreame about her illicit dealings. Only the comic book version of the story provides the confrontation. But the book story includes a romance angle between Donna and Inky that was not a part of the syndication strips. Had it been drawn, the confrontation scene for the syndication strips would have been very different. Personally I doubt that Simon and Kirby produced any more strips, as a syndication proposal it would have been better for the story to be open ended.

The most significant difference between the strip and the comic book versions is the number of art panels that never made it into the comic book story. 43 out of 142 strip panels failed this transition. The first panel from the strip that made it into the comic book was the first one on the sixth strip. This means that 20 earlier panels were discarded. Before the first story page of the comic book was completed a further 4 syndicate panels would be dropped. Thus most of the ignored strip panels come from the start of the story. The remaining unused strip panels do not seem randomly distributed among the comic book pages. One group is associated with the first and second meeting between Inky and Donna Dreame (8 skipped panels for pages 8 to 10). The next story arc with a number of unused panels concerns Donna Dreame’s hatching her scheme with Half-tone (page 12 with 5 unused panels). The next dropped set of panels combines Half-tone arriving at Donna’s place with his first meeting with Inky (page 13 with 4 unused panels). More importantly the section dropped off concerns Half-tone and Donna coming back from a night on the town. Considering the love angle between Inky and Donna that was part of the comic book story this strip was particularly inappropriate. There are a few single skipped strip panels in other parts of the comic book story.

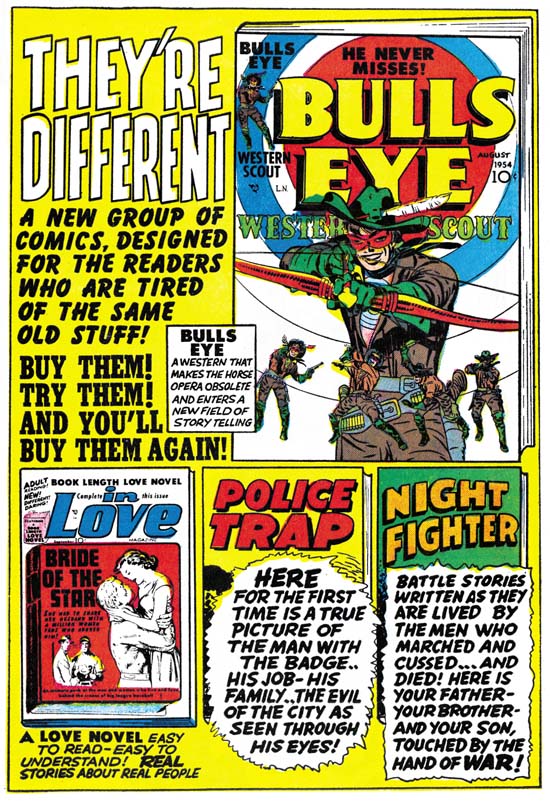

Why so many unused strip panels? At 18 pages “Artist Loves Model” is the shortest of the In Love “novel length” feature stories. “Bride of the Star” had 20 pages and “Marilyn’s Men” had 19. It is possible that the length of these stories was dictated by the number of pages that the backup stories would require and not the other way around. However it seems more likely that strip panels were not used simply because they were not necessary. Even without the extra panels, the comic book version of the story reads just as well as the syndication strips. The only negative effect of the dropping of strip panels is the lengthy caption found on the splash page of the comic book. Even Joe Simon criticized it when he recently viewed the splash page. However the wordy caption probably was considered preferable to the 20 art panels it replaces. That would have added over 2 pages without significantly helping the story.

It does seem that the initial intent was to include more of the early syndicate strips in the comic book story. In my earlier post I mentioned an used page of art in Joe Simon’s collection. This page was made from some of the panels from the third strip. I was incorrect with my original suggestion that this art page was discarded because it was taking the story into a different direction. I erred due to my misidentifying one of the characters as Jack Hill (because I was working from memory). Now it seems to me that this page was abandoned in order to condensed the story’s beginning even further.

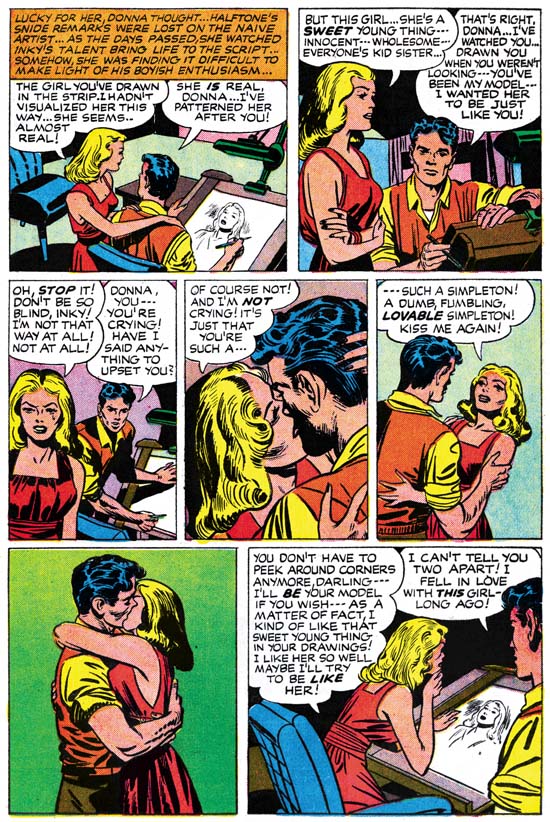

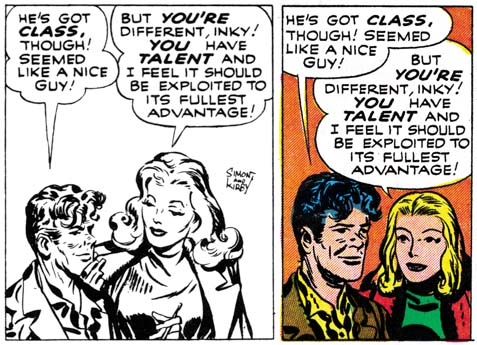

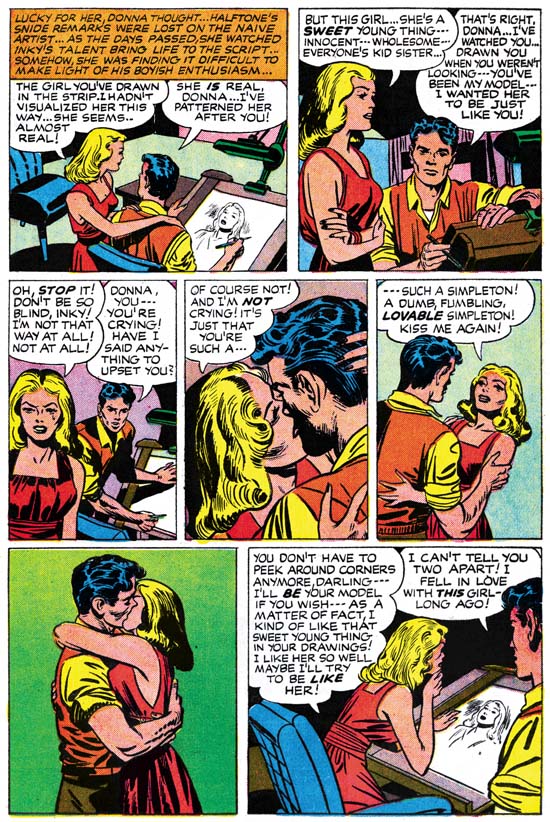

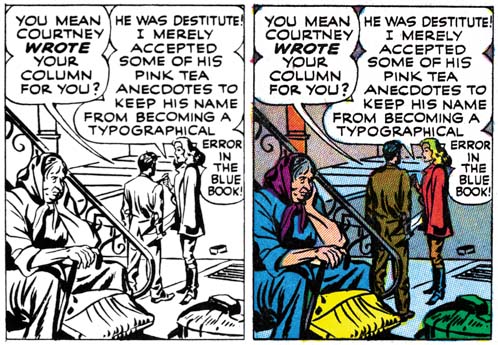

In Love #3 (December 1954) “Artist Loves Model” page 14, pencils by Jack Kirby inks by Joe Simon

Art that did not seem to exist in the syndication strips was added to the comic book. The new art is found in two sections. One is the story arc where Donna Dreame finds out that Inky has used her as a model for one of the characters in the strip they are collaborating on (page 14). A more substantial addition occurs at the very end of the story starting from when Inky confronts Donna Dreame about her dishonest dealings (page 16 through 18). What is significant about these additions is that they concern the romance between Inky and Donna. This romance played no part of the original syndication strip and was added to convert the story for inclusion in a romance comic book title.

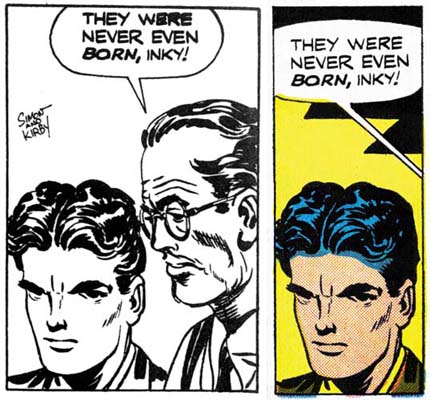

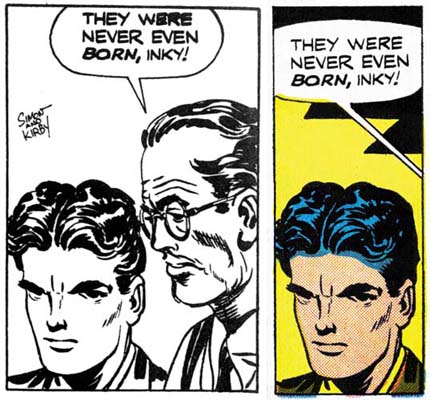

Syndication strip 13 panel 4, art by Jack Kirby from Buried Treasures v1 n2

In Love #3 (December 1954) “Artist Loves Model” page 5 panel 5, art by Jack Kirby

Syndication strip 11 panel 4, art by Jack Kirby from Buried Treasures v1 n2

In Love #3 (December 1954) “Artist Loves Model” page 4 panel 6, art by Jack Kirby

Not all the syndicate panels that did make it into the comic book did so unmodified. The overwhelming majority of strip panels were square. When inserting strip panels into the story 41 of them had their shape altered. 30 panels where horizontally truncated, 10 horizontally extended, and 3 vertically truncated. One of the horizontally expanded panels was used to make a splash panel. This splash was overlaid with another panel so that its shape was no longer rectangular. The new art that was added to expanded panels was kept pretty simple and consisted mostly of backgrounds. Much of the horizontal truncations were done simply by clipping the art. In 2 panels this resulted in the complete elimination of one of two original figures. In 7 occasions where the panel was narrowed horizontally, a character was shifted so as not to be significantly truncated. This explains the unusual cut up nature that I found on Joe’s unused art page. Cutting a strip panel into pieces allowed adjustments to the final shape of the panel for the comic book. It appears that this was done even in cases where in the end the square panel was retained.

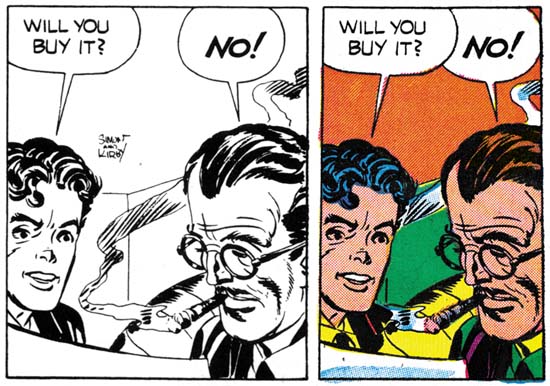

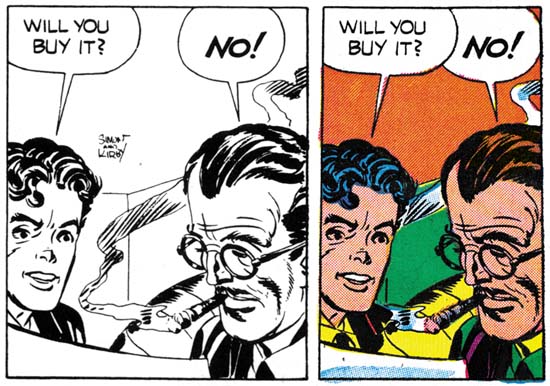

Syndication strip 22 panel 2, art by Jack Kirby from Buried Treasures v1 n2

In Love #3 (December 1954) “Artist Loves Model” page 9 panel 3, art by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon

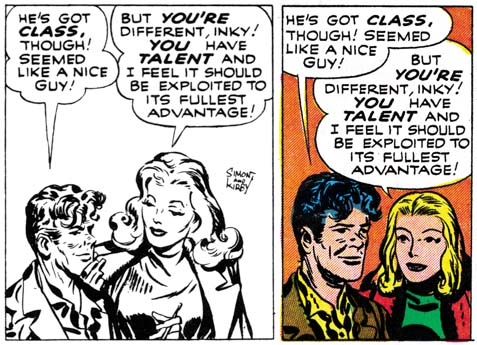

I was not completely accurate above about all the syndicate strip panels that made it into the comic book. Actually I found 14 panels where the art was redrawn either wholly or in part. None of these alterations changed who was portrayed or significantly modified the pose. Most of the time Donna Dreame was redrawn (12 panels), Inky was the only other character to be modified (4 panels). In the syndicate story Inky was portrayed as shorter then most of the other characters. With his short stature and pugnacious nature, I cannot help but feel that Jack Kirby made Inky into a sort of alter ego. The size difference between Inky and Donna may have been fine for the syndicate strips. But this created a problem when romance between the two was added for the comic book, it just would not do to have love between a tall woman and a short man. So in 4 panels Inky was redrawn to be taller. That the romance angle was the reason for this adjustment is shown by the fact that Inky is still shown as shorter then Jack Hill.

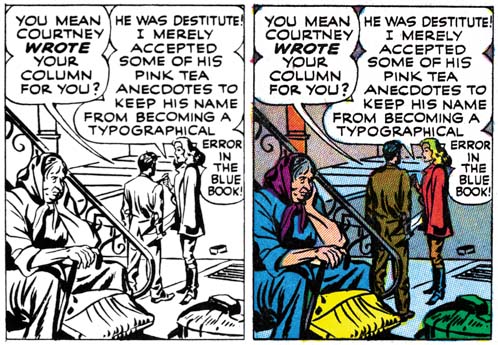

Syndication strip 22 panel 3, art by Jack Kirby from Buried Treasures v1 n2

In Love #3 (December 1954) “Artist Loves Model” page 9 panel 4, art by Joe Simon

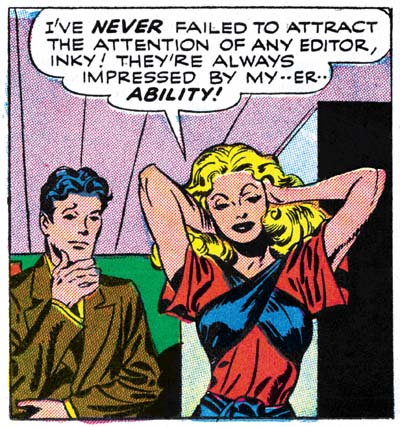

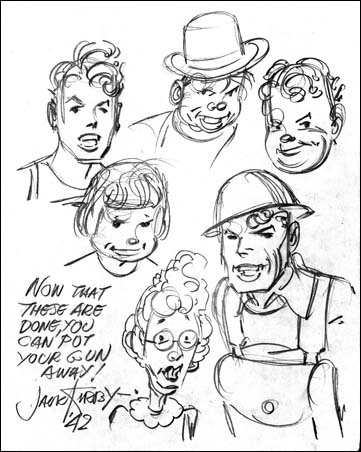

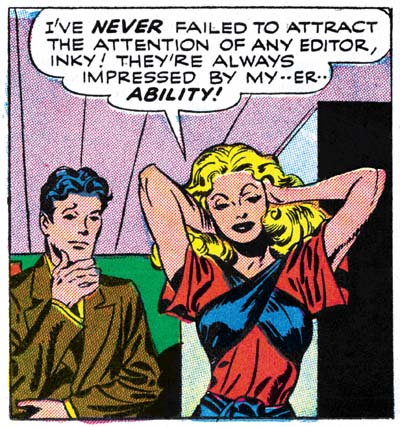

Donna Dreame was altered in a couple of panels as part of the change to reduce her height relative to Inky. That does not explain most of the times that Donna was redrawn. I believe it that these other alterations were done to make Donna more conventionally attractive. Joe Simon once remarked to me that Kirby’s women were not very beautiful, but who cared since Jack drew such great stories. That is a view shared by many others, including Kirby fans. Some have even described Kirby’s woman as ugly. (I hasten to add that I do not share these views and someday I will write a post on why that is.) Joe Simon redrew many of Jack’s women when DC republished some of the old Black Magic stories. Thankfully not all of Jack’s drawings of Donna were redone. This is particular fortunate in the case of a panel which is one of the most sensuous images Kirby ever drew (see image below). Sometimes only Donna’s hair was redone, in these cases the hair was simplified. Kirby used “wild hair” as an indication of a “wild woman”, the hair changes seemed to be done to “tame” Donna a bit.

In Love #3 (December 1954) “Artist Loves Model” page 10 panel 3, art by Jack Kirby

All Simon and Kirby signatures were removed. Other art differences between the syndication strips and the comic book are rarer. Four panels have additions to the background. In two further cases a black band with featuring was added to the top of the panel. All occurrences of Donna’s use of a cigarette holder were removed. Most surprising is a name change, Inky Spotts of the syndication strips became Inky Wells for the comic book. Both names are the sort of appropriate naming that Simon and Kirby often used. It is hard to understand why in the end Wells was considered so much better as to warrant the re-lettering needed to alter the story.

Script changes were not at all extensive. I have noted only two word balloon whose text was modified. One caption from the syndicate strips was deleted and another one rewritten. A caption was added to one comic book panel and most significantly 6 caption panels were added to the book version. None of these affected the plot. All caption additions or alterations seem to have been done just to improve the reading.

Since I have explained the what and the why of the changes made to transform the syndication strips into the comic book story, the question remaining is who was responsible? The syndicate strips had all been drawn by Jack Kirby and much, if not all, of the inking looks like his as well. As for the original syndication scripting, although other writers may have contributed, some of it seems written by Jack. The pencils for the new splash page for the comic book was by Kirby but I believe it was inked by Joe Simon. The same very coarse picket fence inking also shows up in the second splash (page 10) where extending the original syndicate panel resulted in the addition of some art. The art added to the other expanded panels also appears to be inked by Joe. The redrawing of Donna and Inky for the comic also looks like it was done by Joe. Some of the writing for the new or altered captions read like Simon’s effort. However some of the other writing is more “flowery” then typical for Joe, so either he was purposely pushing himself in that direction, or another writer was also involved in the re-scripting. The new art was clearly penciled by Jack but looks different from the rest of the story because Joe did the inking. All in all it would appear that Simon was responsible for editing the syndication strips into the final comic book form with Jack providing newly required art.

Simon and Kirby did a surprisingly number of syndication proposals. Almost all of them consisted of a relatively small number of strips with un-inked pencils. Yet the syndicate “Artists and Models” consists of 36 strips all of which were inked. More significantly, samples were made by George Matthew Adams Syndicate. It is hard to escape the conclusion that “Artists and Models” was considered as the S&K syndication proposal most likely to succeed. The strips do tell a great story and it is one of Simon and Kirby’s best efforts. But I have to agree with Bob of the Jack Kirby Weblog, that it is hard to believe that a comic strip artist could be the basis of enough good stories to keep a syndication strip going for years.