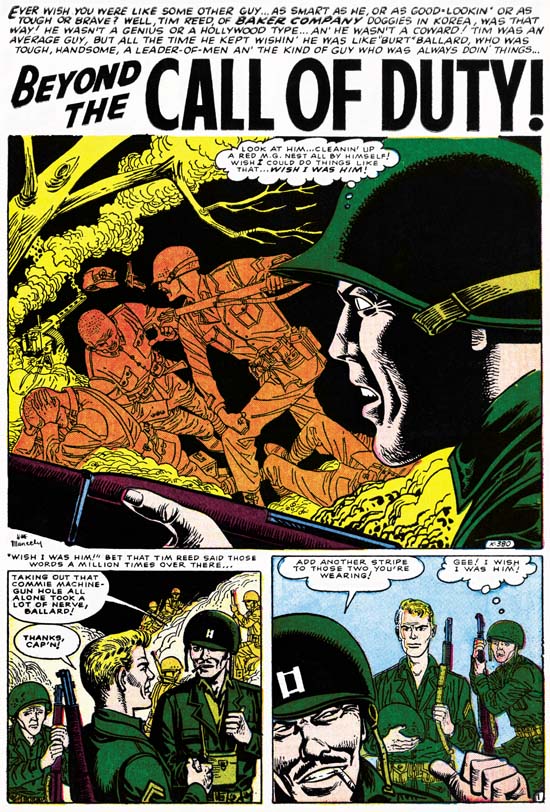

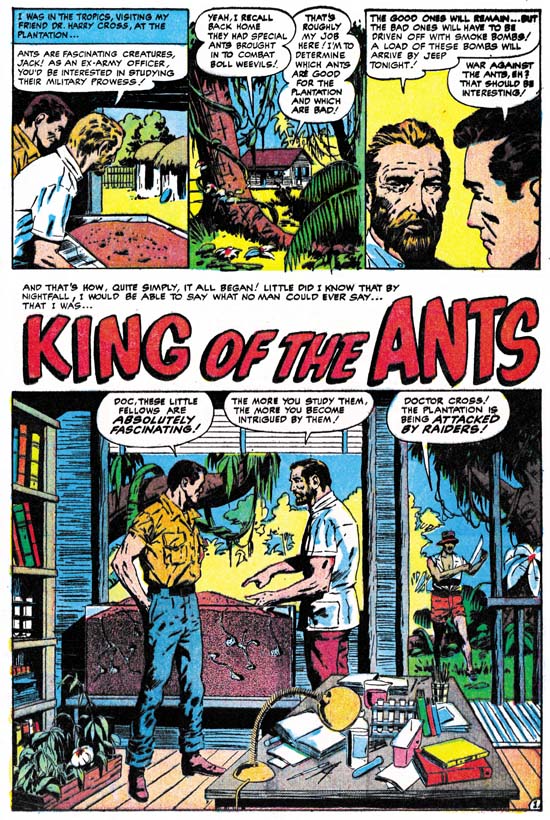

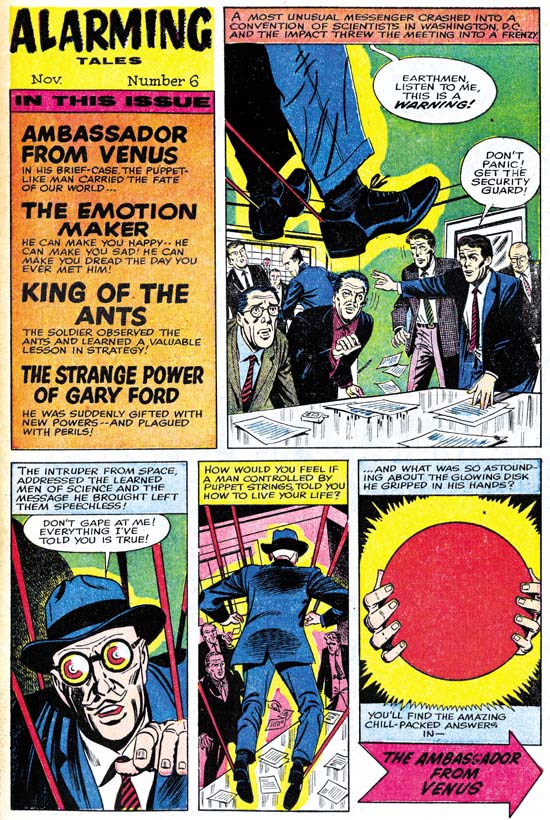

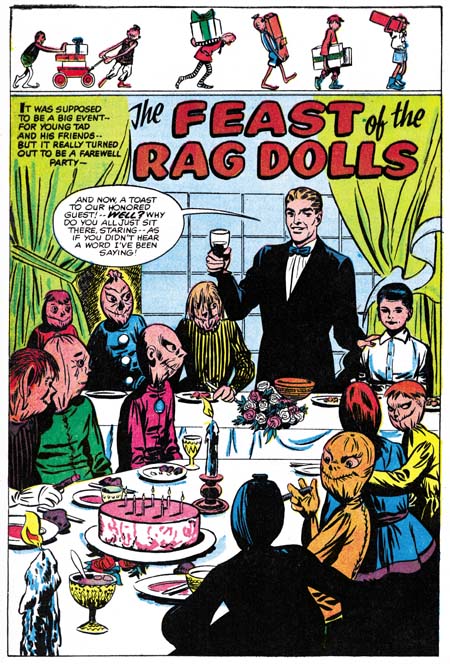

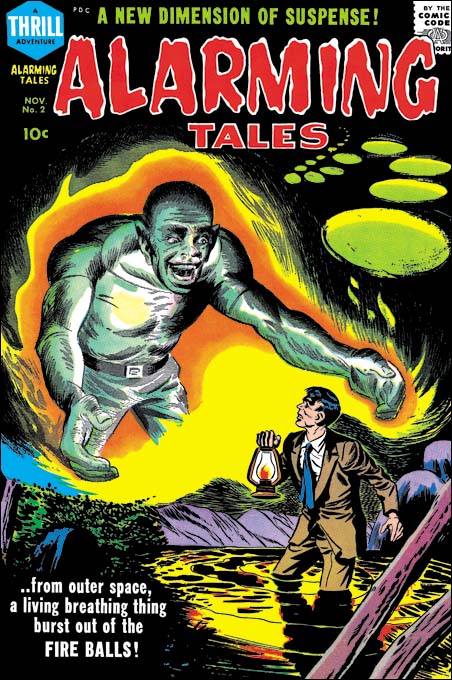

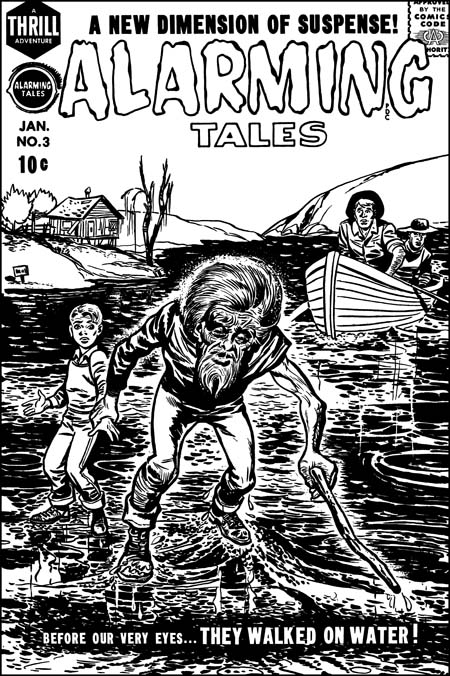

Alarming Tales #3 (January 1958) restored art, by Joe Simon

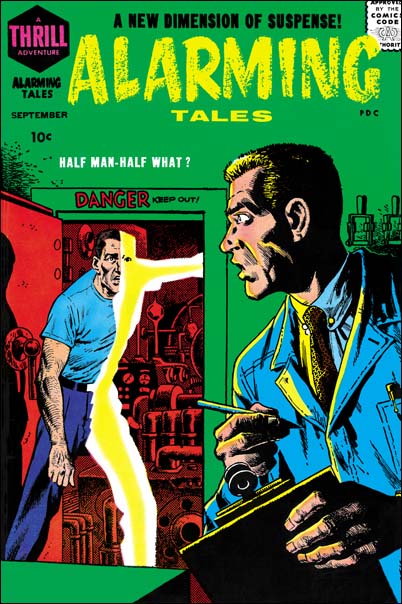

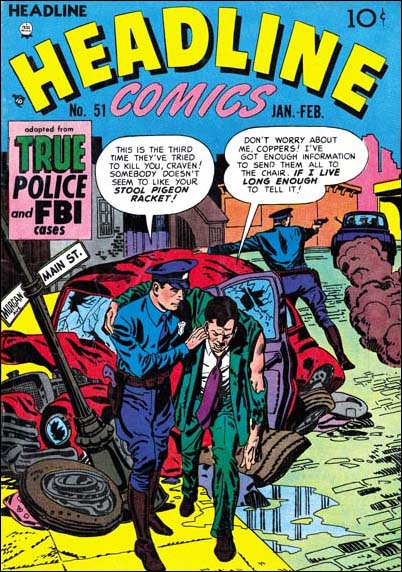

A recurring theme in my posts is how well Joe Simon could mimic Jack Kirby. This has resulted in a number of pieces that Joe did becoming attributed to Jack. Do not get me wrong, the overwhelming number of the items in the Jack Kirby Checklist are correctly attributed. Still there are a small number of entrees that are wrong and it is important to try to correct those mistakes. I would like to say that my study of Joe Simon’s art has enabled me to spot all the attribution errors that others have made. I would like to say that but it would not be completely true. A case in point is the cover for Alarming Tales #3. I provide an image of the restored line art to this cover above, a color version can be seen in a previous post.

In the past I have followed the Jack Kirby Checklist in saying Kirby did this cover. Not everyone agreed, for one sharp eyed Nick Caputo demurred. I was not completely satisfied with the Kirby attribution because I knew of the existence of another version of the cover art. It seemed to me that a comparison of the two would probably resolve the credit issue. As I hope to show in this post, that has turned out to be the case.

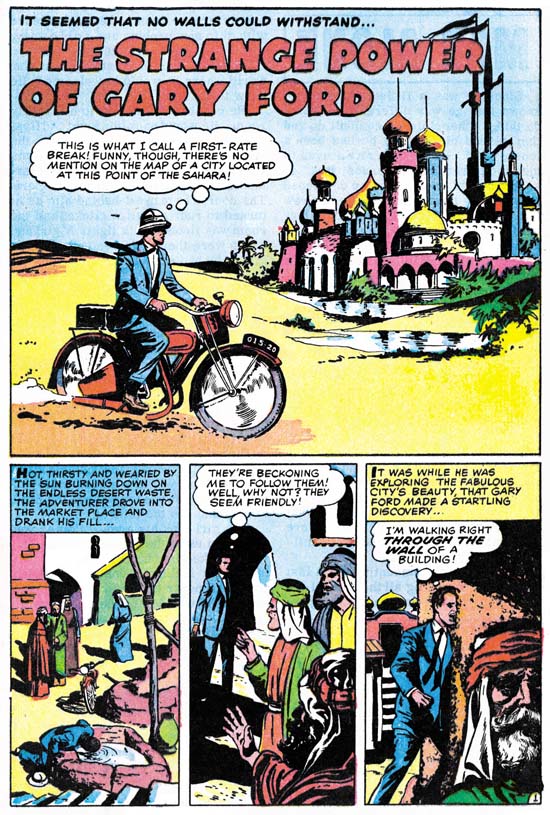

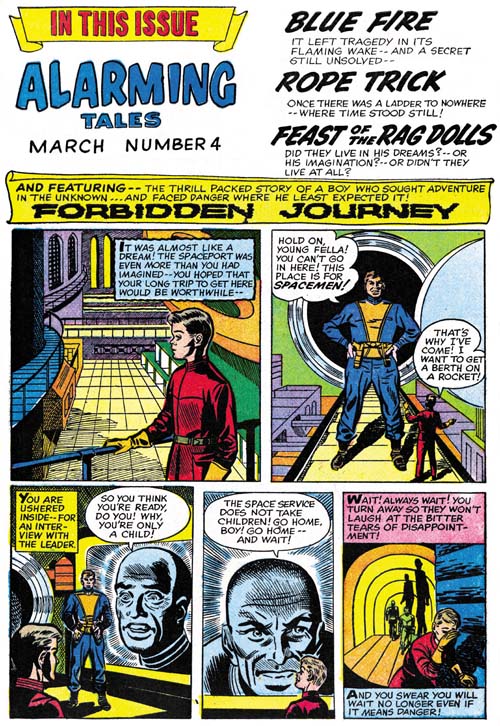

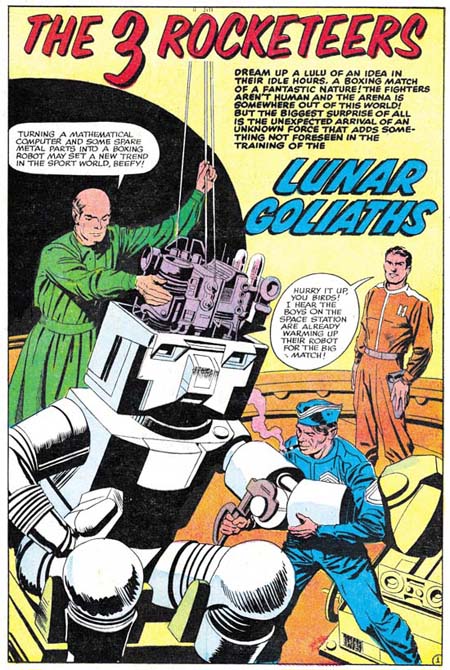

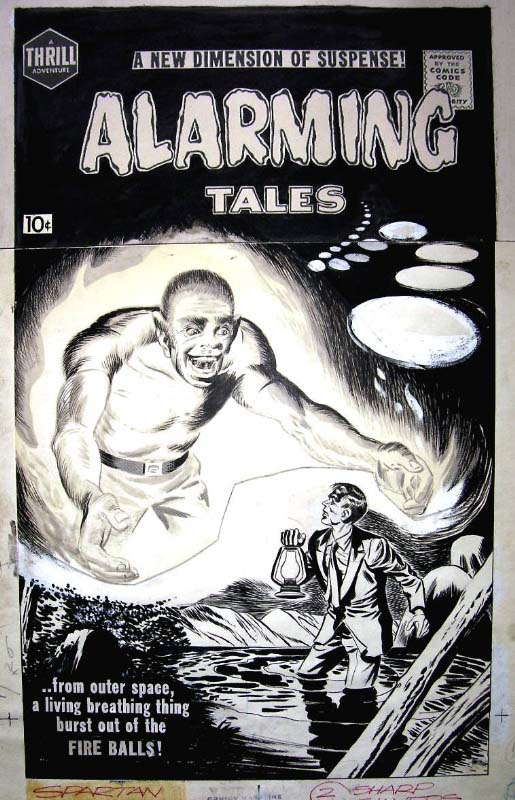

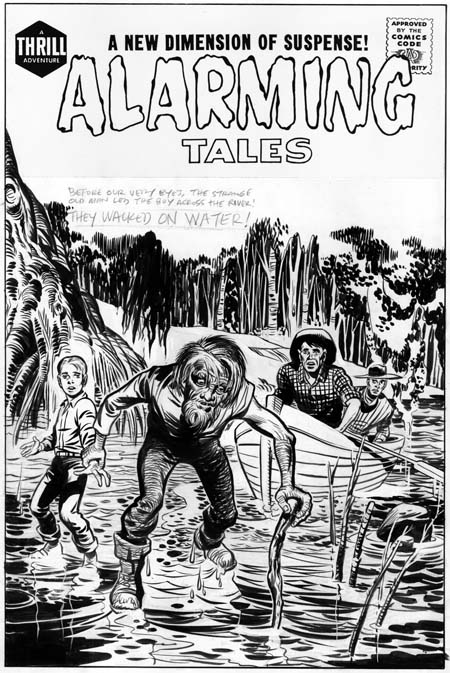

Unused original art for Alarming Tales #3, by Jack Kirby.

I provide an image of the unused version above. A note of caution when comparing the two versions. The unused one is original art and therefore has not been subjected to the blurring and loss of details that are the results of the printing process, all of which the published version has been subjected to. Also the title on the original art is a recent addition. The presence of penciled text indicates the decision to come up with new cover art was made before title stats would have been applied to the original.The derivation of the final cover from the unpublished version is obvious, both have the same cast of characters in about the same positions. The greatest difference is the backgrounds. Not only has the background been completely changed, it has been pushed much further back in the released cover. A closer examination reveals that the people are not identical. The size of the old man has been increased while the relative size of the boy and, even more so, the men in the boat has been reduced. The old man’s head has been enlarged and the position of his left arm has been shifted. The details of all figures have been changed. Curiously the boy’s pants have been given a stripe like those worn by the USPS mail carriers. My original suspicion that reworked stats of the first cover were used to construct the final state was incorrect.I think most readers will agree with me that the original art is more beautiful then the final cover. So why spend the time and effort to replace it? The answer to this riddle is that the purpose of a comic book cover is to entice a viewer to purchase it. To do so it must stand out from the rest of the comics on the rack. The problem with the original version is that the old man is overwhelmed by the background. By simplifying and pushing the other elements back, the old man and his feat of walking on water becomes more obvious and dramatic. It is a question of design taking priority over artistry.

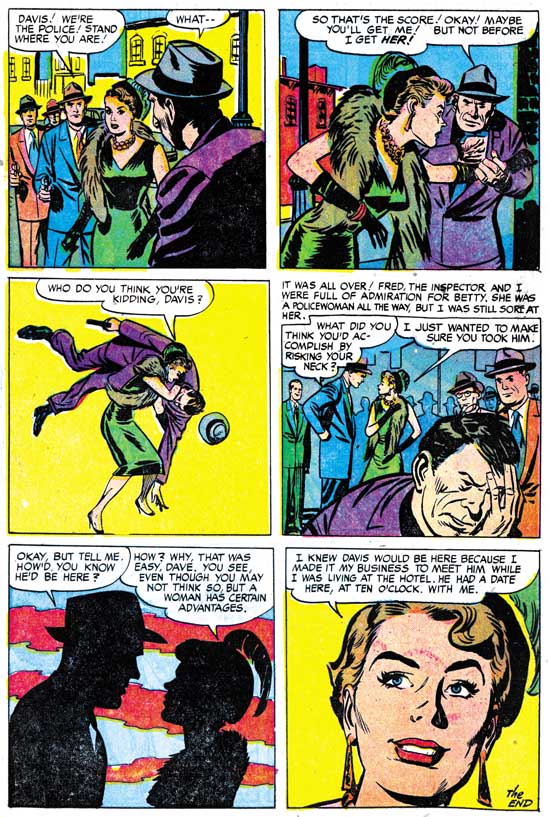

Close-up of the old man by Jack Kirby and the Joe Simon rendition.

Because the compositions of the two versions are so similar, we must look at the details in order to arrive at the correct attributions. Although not a standard part of Kirby’s repertoire, the old man of the first state seems to be not only his pencils but his inking as well. There are subtleties that his copyist is unable or unwilling to capture. Some of the alterations do seem on purpose, in the final state the old man has been made older and more frail. In doing so the published version has lost the quiet dignity and resolve that the original old man possessed.

Close-up of the young boy by Jack Kirby and the Joe Simon version

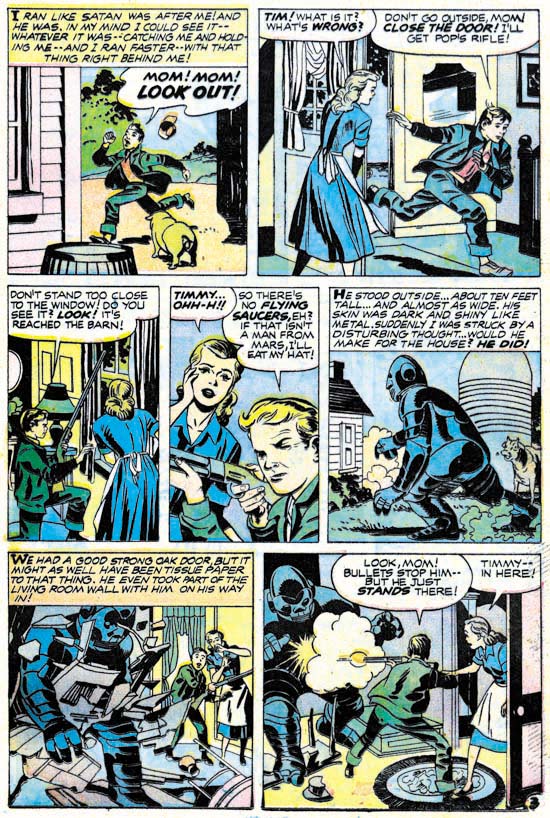

Personally I do not find much in the final state of the old man to suggest who was responsible. For an answer to that question I turn to a close-up of the young boy. Once again the original version seems to have Kirby’s touch all over it. Some of Jack’s style has been preserved in the published interpretation but purposeful alterations have been made as well. Frankly in Kirby’s hands the boy has been given a somewhat dim witted response to his predicament. The copyist on the other hand has widen the boys eyes, raised his eyebrows and furrowed his forehead. All this gives the boy a more intelligent and surprised reaction to being lead by the old man over water. It is the boy’s eyebrows that convince me that the copyist is Joe Simon. Similar eyebrows crop up often in Joe’s work going back as far as the cover for Champ #19 (June 1942) .

The men in the boat are typical Kirby creations. Unfortunately it is hard to compare the two versions because in the published one they have been reduced in size and their finer features lost by the reproduction process.

I mentioned above that I believe Jack Kirby inked his own pencils for the unused Alarming Tales #1 cover. That is not surprising because AT #1 is a comic where Jack did most of the work, including the inking. When I previously discussed the inking in AT #1 I found some of it similar to the standard Studio style while others were closer to the Austere style. On a whole I felt the material was transitional between those two Kirby inking methods. The inking style exhibited on the unused cover is a bit of an anomaly. It is true that the bow of the boat exhibits what looks like typical picket fence brushwork (see the Inking Glossary). It should be noted that it is unusual for the rails of a picket fence inking to depict literal objects like it does here with the bow edges. A better example of typical Kirby brushwork can be found in the folds of the boy’s shirt. They exhibit the tendency to be flatter then the underlying form that was common for Kirby at this time. The form lines on the tree on the left side of the image also look like Jack’s. But other inking methods used are very unusual for Jack, in particular the form lines on the old man’s pants. I do not recall Kirby ever doing something like that before.

Also unusual about the inking is the abundant use of white-out. Although Kirby was a bold inker his control was so great that he usually had to make few adjustments with white-out. Actually some of the white-out on the unused cover were not mistakes at all. Many of the trees in the background and some of the branches in the water were actually created by white-out. The old man’s hair was done by a combination of standard inking and the use of white-out. But mistakes were corrected, for instance the edges of the drooping fronds left of center on the top were worked over. Some earth lines in the background and a water stain on the upper part of the boat were removed. I am not sure what to make of Jack removing the bottom of the boy’s shoes. Perhaps it was done to indicate that he the lacked the old man’s confidence and so could not tread as lightly over the water surface? A most surprising correction is found in the depiction of the water, much of what now looks white has abundant use of white out. The white-out does not completely hide the underlying inking and judging from their faint markings the water surface was originally much darker.

Despite all the features that are not usually found in Jack Kirby’s inking, I find the combination of boldness and control so characteristic of his work that I am pretty confident to credit him with the inking. The published cover shows Joe Simon equally bold with his use of the brush but without the same nuance of control exhibited by Kirby. It is interesting that Joe made the water surface very dark, just the thing that Jack spent so much effort to remove from his own version.

I love comparing different artists’ versions of the same subject. It is not a question of trying to determine who the better artist is. What I find interesting are the different decisions each artist made and what the reasons for those decisions were.