There already are numerous essays about Joe Simon’s life on the Internet written by people much more talented than me. The biggest problem for me is how to condense such a productive live into a article short enough that people would actually read without leaving too many important things out. Perhaps I will give it a try later but I thought instead that I would provide a more personal narrative about Joe.

I don’t count the time when I had him sign a Fighting American page of original art as the first time I met Joe Simon. That was at a Big Apple Con when it was held in the basement of St. Paul’s church. The noise level was so high and Joe’s hearing so poor that you could not have any real conversation with him. Still Joe was very kind to me and the other fans even though he was not making any money from us for his signings nor was he selling anything.

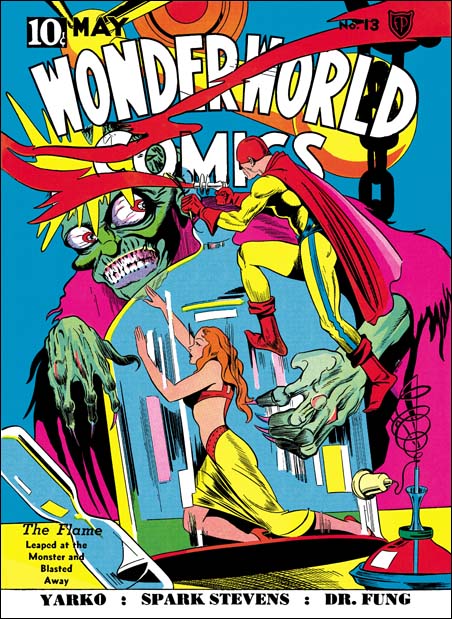

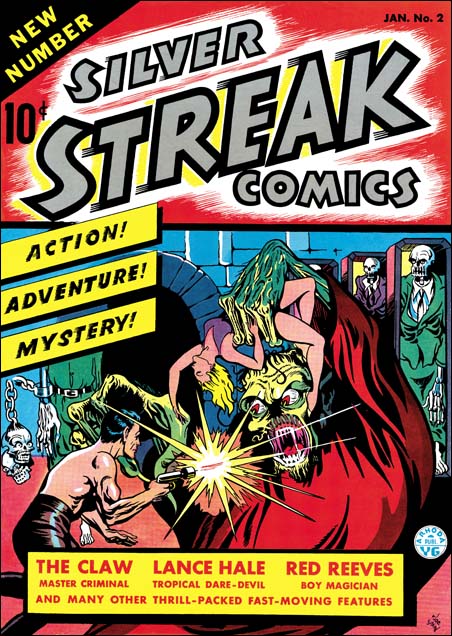

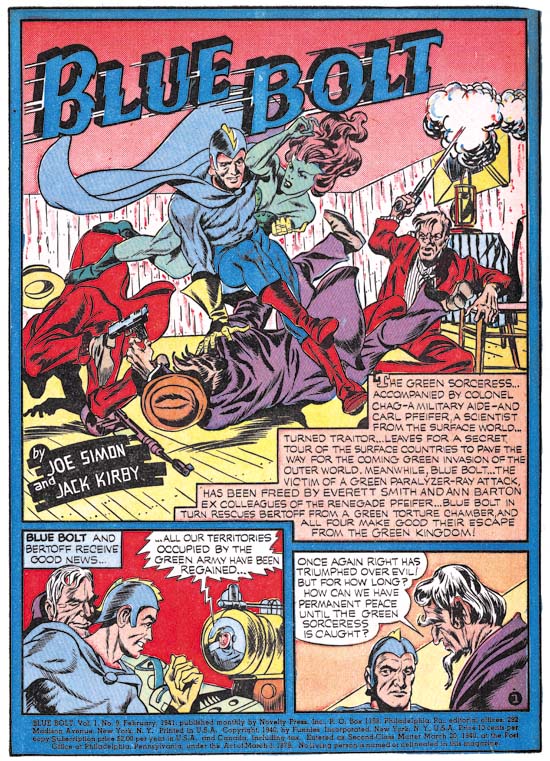

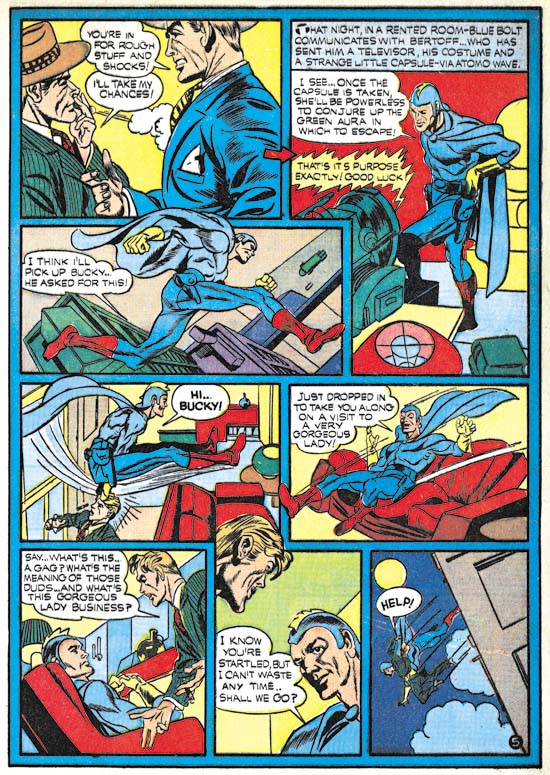

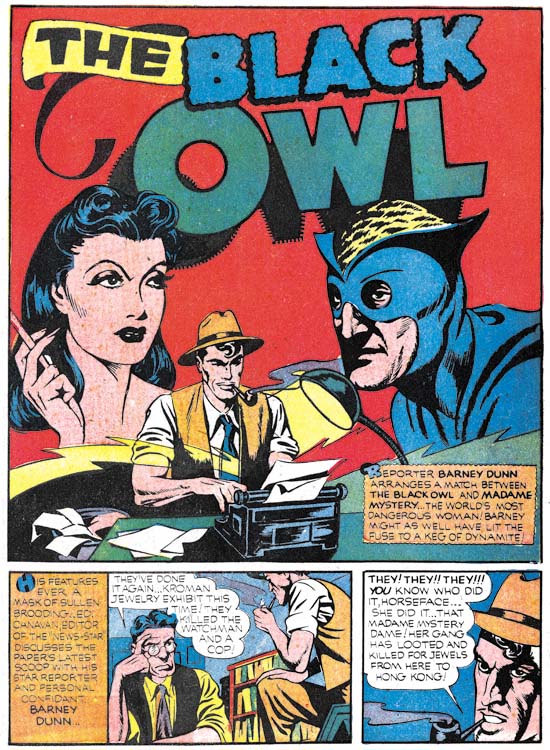

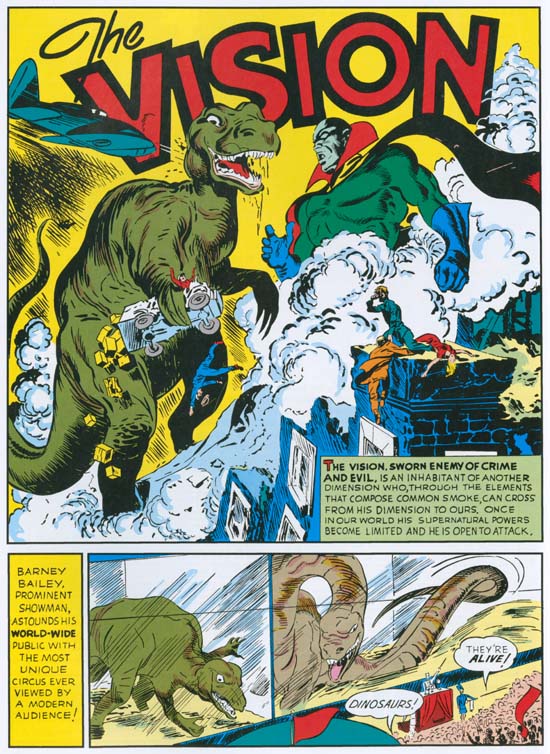

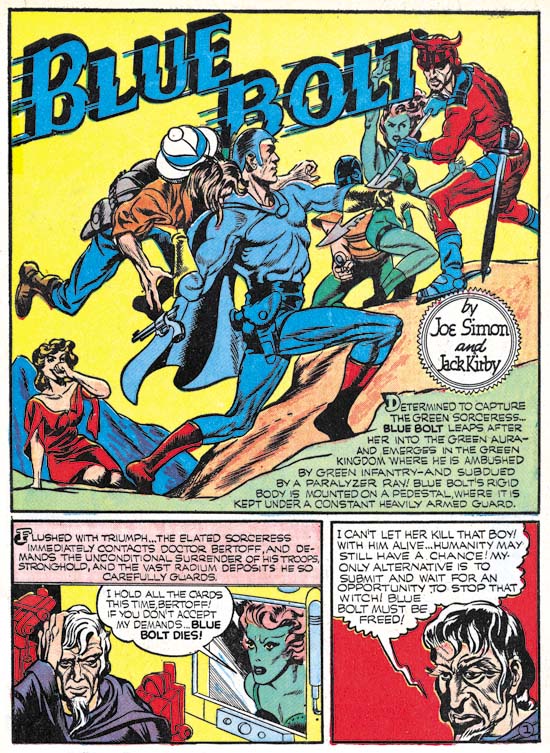

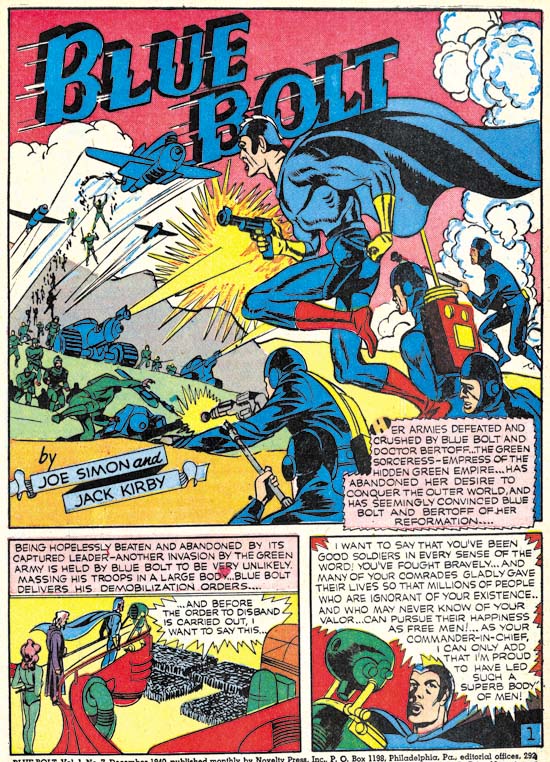

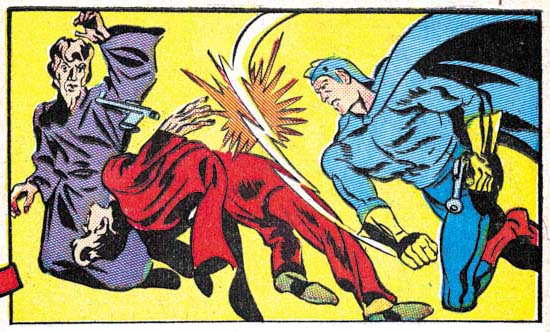

For me the first time I really got to meet Joe was at another Big Apple Con this time held at a convention room where you could actually have conversations. I was a big Simon and Kirby fan and had recently embarked on a project to digitally restore the line art to all the Simon and Kirby covers. It was an ambitious project to say the least and at that time I only had completed maybe fifty covers. I decided to make 11 by 14 inch prints of the three Champion covers for Joe and bring along the notebook of the rest of what I had done to show him. Hey what can I tell you, I was and still am a fanboy. When I gave him the Champion prints he stopped, looked at me and said “I am not mad or anything, but how did you manage to get a copy of my restoration of this cover, I just did it a couple of weeks ago”? I tried to explain that they were my own restorations and how I did it, but he was unconvinced and calmly repeated his question. We went around and around on this a couple more times with Carmine Infantino stepping in to try to explain to Joe what I was saying. But it was only when Joe began to notice the small differences between his recreation techniques and mine that he began to realize that it was just a coincidence. But during this whole exchange Joe was calm and friendly, I doubt I would have been if I had been convinced that someone had gotten a hold of my private work. Joe was interested in my project and I offered to give him copies of my restorations. Periodic visits to Joe’s apartment followed as I continued to do line art restorations of Simon and Kirby covers.

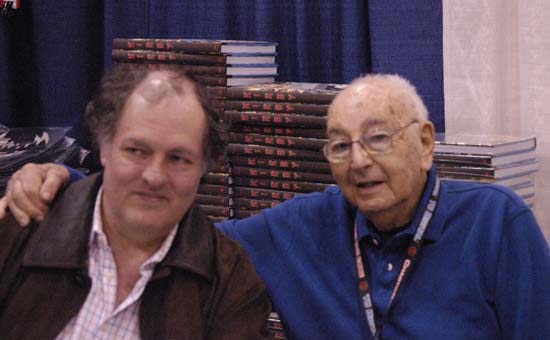

Joe with Mark Evanier signing Mark’s book “Kirby: King of Comics”

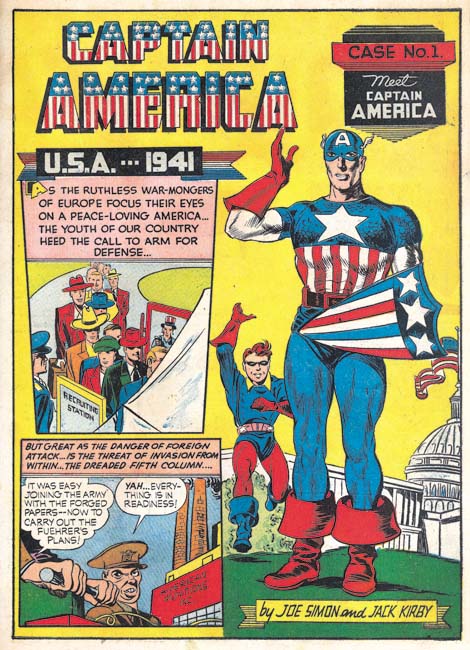

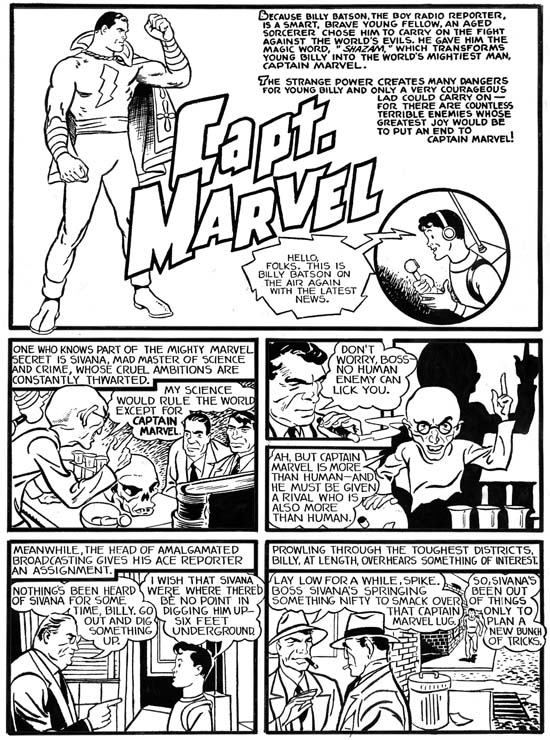

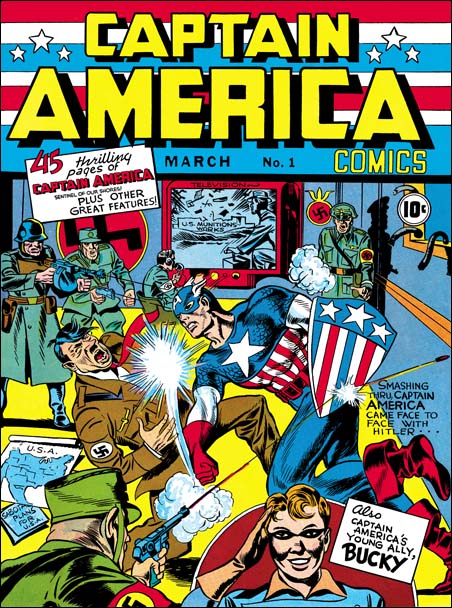

Joe was not anything like I expected him to be. If I were to condense the stories I had previously heard it would come down to that Joe was always claiming credit for what others, usually Jack Kirby, had done. All I can say is that this is not the Joe I came to know. For my visits I always brought Joe copies of my latest restorations. I was very interested in what Joe would have to say about them. You could tell Joe enjoyed viewing them very much. He would often make comments like “I had forgotten about that cover”. During the viewings Joe would frequently remark on how talented Jack Kirby was. But it was rare for Joe to say that he, not Jack, had done a particular cover. My experience was that when he took credit for some work he was almost always right. During this time Joe became involved in a lawsuit with Marvel over Captain America copyrights. On the Internet comic fans were often very critical of Joe for doing this, saying that Joe was unfairly trying to exclude Kirby from any credit. However I remember a diner I had with Joe and Carmine Infantino. Joe would not go into any details about any possible settlement with Marvel, but he did say that as part of any agreement Marvel would have to add to the Captain America comics a “created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby” byline. The details of his settlement that eventually was reached with Marvel were kept confidential but I do not think it was a coincidence that shortly afterwards Marvel began to include creator credits to Simon and Kirby in their Captain America comics.

Dick Ayers with Joe and New York Comic Con 2008

I have rarely read an interview of Joe Simon that I thought was any good. Not only were Joe’s answers generally not very informative but they also did not seem to lead the interview along. The Joe presented by these interviews turned out to be another example that was very different from the Joe I got to know from my visits. In this case I feel I understand why the interviews were so unsuccessful. During my initial visits I would ask Joe questions about specific covers or about other detailed issues that I as a fanboy was interested in. But Joe never seemed able to provide answers. The problem was not that Joe was trying to conceal anything nor did he have a bad memory. In fact I found his memory to be quite excellent. Joe could remember the address of the various places he worked. He could even remember the address of a store he used to buy his cigars back in the 50’s. However Joe’s memory was good for the things he was interested and that generally was not the same as the things that a comic aficionado wanted to know. I soon found that I learned more if I just provided copies of work and just let Joe respond as he wanted. When I asked questions I would keep them general. Not that it always worked, but sometimes it would get Joe into telling stories. Joe was a natural, he told great stories. Carmine Infantino once said to me that Joe was one of the best comic book writers, he just did not get the credit for it that he deserved. If you never had the opportunity to hear Joe telling stories then I suggest reading his book “The Comic Book Makers” or the more recent “My Life In Comics”. But do not read like a comic fan for its history, read it for what it is, a collection of stories. Do not look for what you want instead just follow Joe’s tales. That is not to say that there is not a wealth of information in these stories. However I will say that if you try to mine his stories for information you should remember one of Joe’s sayings, “never let facts get in the way of a good story”.

There was one glaring exception to all too often poor interviews of Joe, the one done by Jim Amash for Alter Ego #76. Now much can be said about what a great interviewer Jim is. Amash has many qualities that help to make his work with Joe and other comic artists so successful. His wide knowledge of the subject and experience from years of conducting interviews to name just two. But Jim also had a something special going for him, he was Joe’s friend. During many hours over the telephone Joe opened up to Jim in a way that he only would with a friend. Joe would often grumble to me about how much time he was spending on this interview with Jim but that was all bluff. I could tell how much Joe was enjoying it and Joe never did anything he did not want to. If you want to get some idea about what Joe was really like I can think of no better source than Amash’s interview.

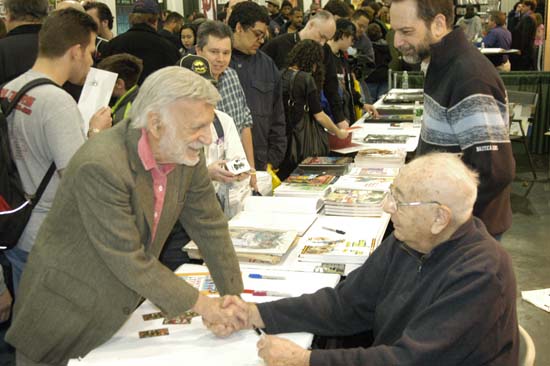

Jerry Robison greeting Joe at New York Comic Con of 2005

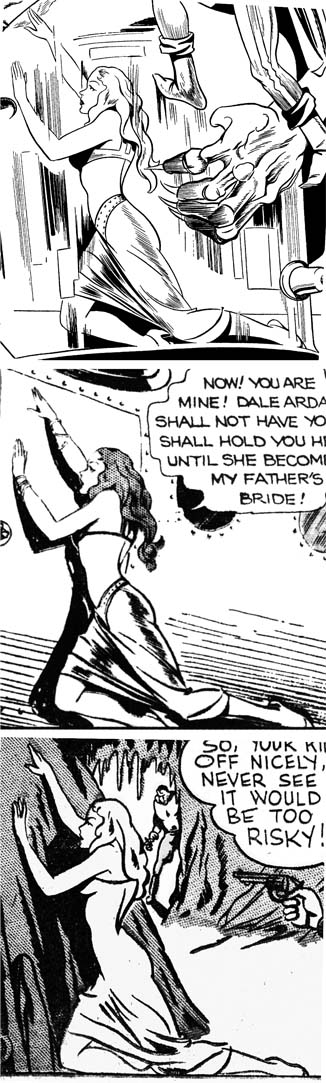

Some consider Joe more that of a businessman then as an artist. When I was first getting to know him I sometimes felt that he wanted to believe that also. But even if he did it still was not true. Joe’s response to the cover restorations were always artistic. Sometimes he would suggest ways that the cover could be improved. A figure should placed further from the motorcycle it was leaping from. A different color should have been used in a particular spot. Sometimes Joe would make copies of original art in sections that he would then have to recombine. I watched him once start to use acrylic paint to retouch one of these to hide the edges between the sections. That is what he started to do but Joe ended up redoing much of the art itself. Joe had intended to make a reduced size copy of the original art and ended making a new version of it. One time Joe copied a piece of original art from his old magazine Sick. The art showed a giraffe with rabbit ear antennas coming out of its head. Joe was concerned that today few would know what the rabbit ears were so he retouched it replacing them with a satellite dish antenna. When I arrived once for a visit Joe told me that recently he had been taking xerox copies of one of his drawings of Captain America and hand painting them. Joe said that somehow he found this very relaxing. Sure enough I was able to look through a pile of these Cap pieces, all the same yet each one unique.

Tom Morehouse and Joe with the original cover art for Police Trap #2

I helped Joe at a number of comic conventions which gave me an opportunity to see Joe interact with comic book fans. At one Joe walked around the tables talking with various comic book artists. He was always quick to provide complements when he saw anything he liked. But even though some were showing pieces of Captain America, I got the feeling that none recognized who they were talking to. At the next show Joe did a similar tour of the artists but this time the artists would often realize at some point who Joe was. It was always amusing to see a comic artist turn from being a professional to just another fanboy. If they had a camera, they always wanted their photograph to be taken with Joe. He treated regular fans well also. At the shows Joe was promoting his reprinted edition of “The Comic Book Makers”. Joe would prepare some copies with a full color work of Captain America inside that would be sold at the show. Joe would also do quick sketches of Cap in books at the show. Yes Joe made money for this work but many of them immediately ended up on eBay where they were sold for up to twice what Joe charged. Joe was well aware of this but it did not bother him at all. Like most artists Joe was happy to sign what ever the fans brought. One fan had an unfinished drawing with a large stain on it. Joe said he remembered it but that he threw it away uncompleted because he spilled coffee over it. Someone had fished it out of the garbage and sold it on eBay. Joe chuckled about what had occurred, was a bit surprised that anyone would value such a damaged and unfinished piece, but he was happy to signed it.

J. David Spurlock, Joe and Roy Thomas at the 2005 Big Apple Con

Joe had a certain irrelevant humor about comics and even himself. When a major comic publisher sent him a royalty check for fifty cents, Joe framed it with a doctored picture of himself. To the picture Joe added a cup, scruffy hair and an eye patch transforming himself into a street beggar. During one of his legal battles over Captain America copyrights Marvel threaten to kill off the character. Joe proceeded with the help of his daughter Gail to paint a version of Leonardo’s Last Supper replacing Jesus with Captain America and the disciples with various super heroes. The meal itself was populated with numerous modern products. Joe had a penchant for cutting off pieces of his hair, adding them to a photograph of himself and then making from this a xerox. He would say he wanted to improve the look of his hair, but you could tell he knew full well how ridiculous the final results looked.

Joe and Stan Lee at the 2008 New York Comic Con

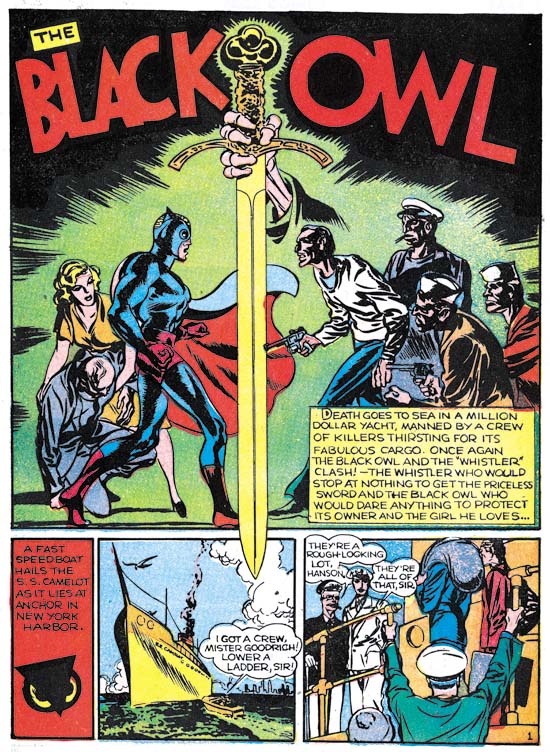

I only got to know Joe during the final years of his life but I did get to see at first hand a change in how Joe was perceived by the public. Earlier it often seemed that when Joe was not being ignored by comic fans, he was being abused by them. Joe once commented about a Kirby list on the Internet was that “they all hate me”. While that was not strictly true it was not all that far off from the mark either. Our attempts to get a publisher interested in reprinting Simon and Kirby work all seemed to fail, they just were not interested enough. When Joe was remembered by comic book fans at all, they usually viewed him as the one who handled all the business while Kirby took care of all the art. Over the years and little by little this neglect by the public began to change. I like to think I played my small part in making that change happen. Joe lived to hear Stan Lee describe seeing him draw Captain America alongside Jack Kirby, what a wonderful artist he was and how Joe was his mentor. And to read Neil Gaiman praising him as a great writer in the introduction to the Superheroes volume of Titan’s Simon and Kirby Library. Joe never made a big deal about these and other praise that he began to receive but I could tell it was very gratifying to him. Finally a publisher, Titan, was found with the foresight to begin reprinting some of the Simon and Kirby work. I saw first hand how excited he was to see the initial volumes that have been released by Titan. Unfortunately there was a negative consequence to this change as Joe lived to see others rush to reprint material before Titan could get it out so that once again Simon and Kirby would be exploited by a publisher. I will say that once Joe realized that this publisher would not be swayed by appeals to fairness he became very philosophical about the matter and did not let himself be upset about it. His final year was a particularly good one for Joe. During that time he saw the publication of his autobiography “My Life In Comics” and the release of the Captain America movie. Both of these gave him much pleasure.

Steve Saffel, Joe and two grand-daughters at 2011 New York Comic Con

I could go on writing about Joe Simon. After all I have been writing about Simon and Kirby in this blog for almost six years. But I fear I have already been rambling too long in this post. Joe was important figure in the history of comic books, truly a legend. It has been my great fortune to have been able to get to know the man behind that legend, to work with him and to be his friend.

Jerry Robinson and Joe at the 2008 New York Comic Con