Simon and Kirby always seem to put special effort into their covers. So it is on the covers that we are most likely to find the use of techniques such as picket fence or drop strings. In the last chapter we saw how in the Prize romance interior art these Studio Style methods disappeared by the end of 1956. What occurred on the covers was a bit more complicated.

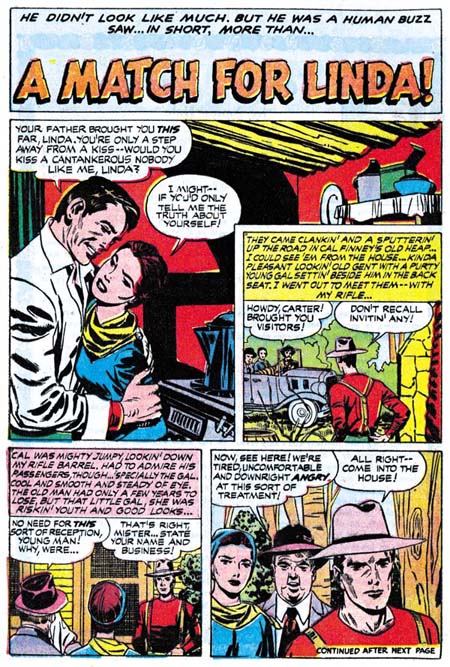

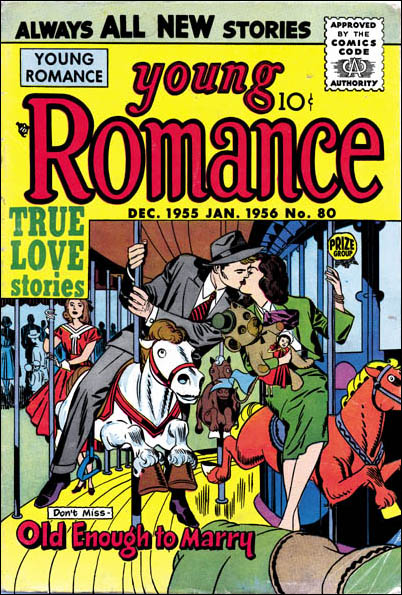

Young Romance #80 (December 1955) pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

The YR #80 cover was the first cover that Jack did upon returning to working on Prize romances. At first look one might believe that Kirby had immediately jumped into the Austere Style. Nowhere do we find any picket fence brush work and only a limited use of a drop string like technique. However the absence or limited use of these special brush work was probably due to how complicated the image was. Without the colors this becomes a difficult image to read. Because the surface was already so busy it would have been difficult to add picket fences. So the absence of picket fences can be misleading. What spotting there is more closely resembles the use in the Studio style. Later in this post I will present another cover truly done in the Austere inking which will highlight the difference between that style and what was done for YR #80.

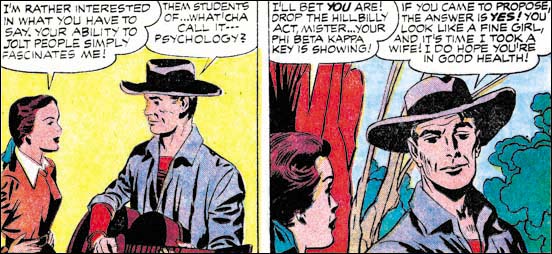

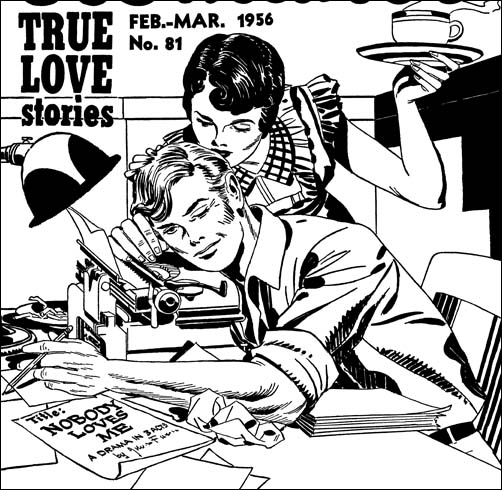

Young Romance #81 (February 1956) restored line art, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

YR #81 is an cover inked by Jack not long after his returned to working on the Prize romances. In the previous chapter I gave examples from the interior art of this same issue for both Studio and Austere style inking. The cover seems a good example of Studio style work. In fact if you did not know what was coming it would be easy to overlook the ways that it deviates from previous work in this style. The picket fence patterns are done every so slightly in a finer manner. Some of the spatulate cloth folds on the man’s shoulder seem more typical of the Austere style. Note how they just seem to attach themselves to fine ink lines almost like they were leaves. Also there are some fine form lines used in the man’s forearm. The entire image has a lighter look to it without being anywhere near as light as the true Austere inking. But I want to repeat that none of this would be particularly surprising except in view of what is to come.

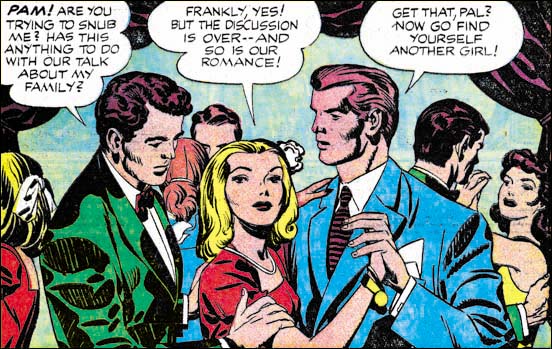

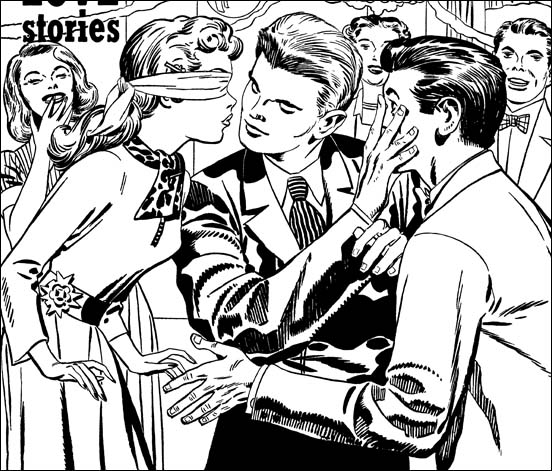

Young Romance #82 (April 1956) restored line art, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Jack’s next cover for Young Romance looks rather different from the standard Studio style. It has the overall lighter look typical of an Austere piece. Yes there are blacks but they have been concentrated on the young man at the center. Elsewhere most of the spotting is rather sparse. In many respects it is a good candidate for showing the evolution from Studio to Austere inking. But look at all the drop strings and picket fences. It is not their presence that is surprising is the fact that they are now done with much finer brushings. This is the start of what I am going to refer to as the Fine Studio style. It might not warrant a special designation if it was limited to these Prize romance covers. However we are going to encounter it again when Kirby begins freelancing with Atlas.

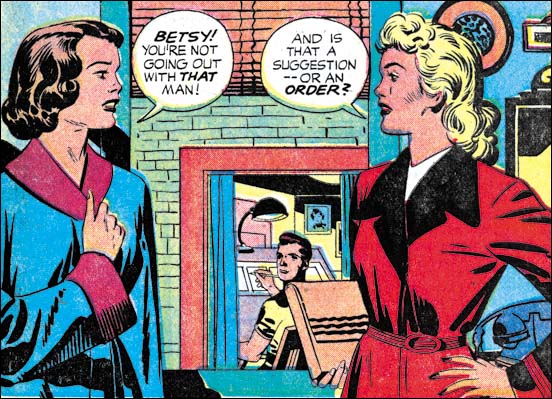

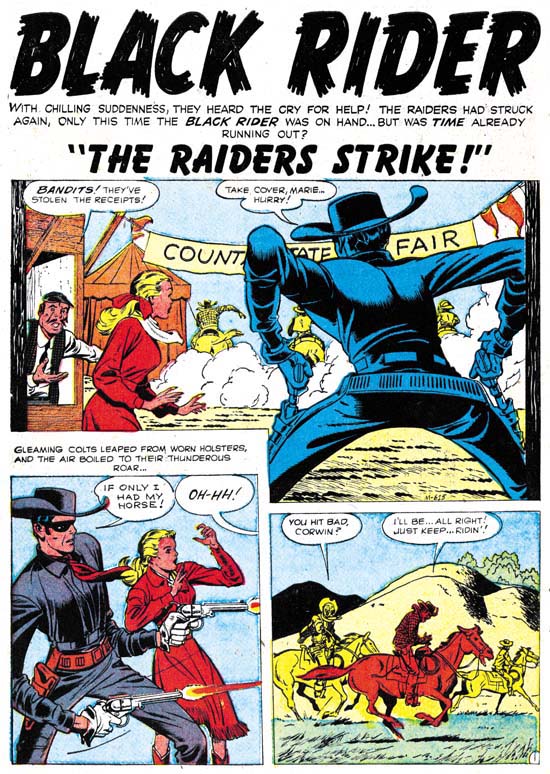

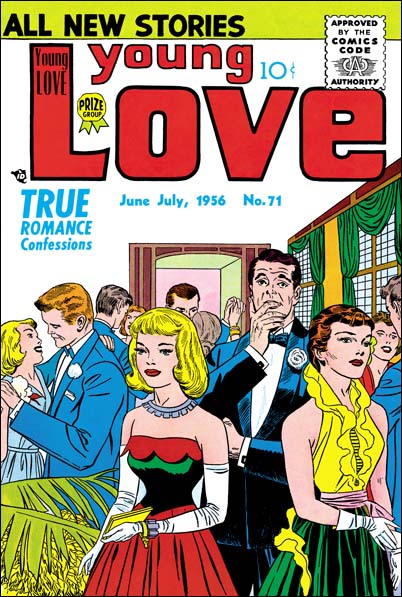

Young Love #71 (June 1956) pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

About midway through the year, Jack provides a cover that can easily be said to be done in the Austere style. Note the lighter look and the simpler treatment of clothing folds. When blacks are used they tend to flood the area as in the jacket of the man or the woman’s blouse. The ink lines are so fine that I originally thought they were done using a pen. However I have seen the original art for this cover in Joe Simon’s collection and it shows that a brush was used. Note how the folds in the jacket of the man dancing on our left seem concentrated in the elbow and shoulder regions leaving the other areas of the arm relatively plain. Although a complicated image with lots of background figures, this cover still looks very typical of the Austere style. It makes a good contrast to the Studio style used on the cover for YR #80 that I showed in the start of this chapter.

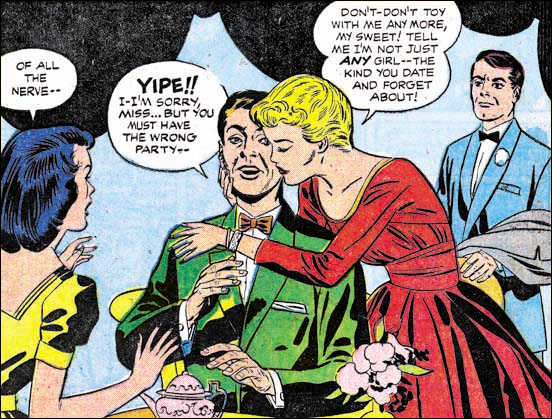

Young Brides #29 (September 1956) restored line art, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

This is excellent example of Jack Kirby’s Austere style in inking a cover. The over all image has a very light appearance. Black is used, here in the blouse and hat of the lady on our left, by flooding the area with ink. Some of the brush work looks like a modified drop string but are for the most part done in an overlapping manner forming a ragged line.

Once again I cannot restrain myself from commenting about the art. The cover shows some celebrity surprised while signing an autograph by a kiss from an adoring fan. Very charming. But you can still see the celebrity signing the autograph book. So how did the attractive lady get into his arms? Of course she could not if we tried to interpret this cover as if it was done by a camera. But this is not a photograph nor should it try to act like one. Although not logical as a frozen moment in time, this cover makes perfect sense when view as presenting a story. Had it been more logical the story would probably have been less clear.

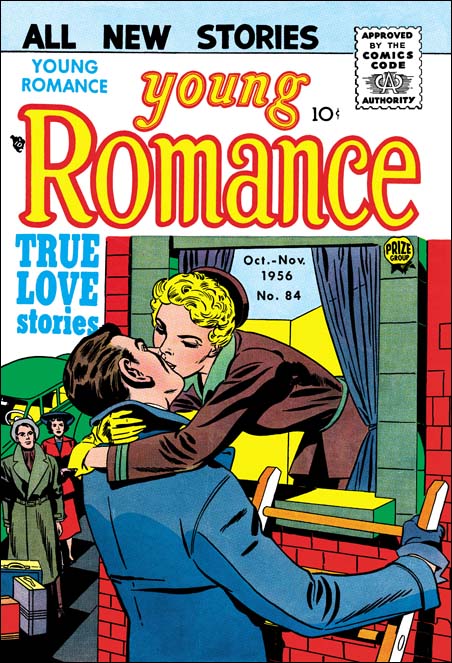

Young Romance #84 (October 1956) pencils by Jack Kirby inks by Bill Draut

This serial post is about Kirby inking Kirby. Still during this year Jack did not ink all of his pencils. So I like to include examples of other inkers of his drawings. The above image of YR #84 looks like it was inked by Bill Draut. It is interesting to see how Draut’s inking also has the lighter quality present in the Austere Style. While Kirby’s pencils did not provide any guides to the spotting, it did indicate where things like clothing folds should be placed. The more limited use of such folds gives the image the lighter look. Spotting was still up to the inker as indicated by Draut’s different handling of the woman’s jacket.

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 1, Introduction

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 2, Mainline

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 3, A Lot of Romance

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 5, Harvey

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 6, Atlas

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 7, DC

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 8, More Harvey

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 9, More Prize

Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, A Checklist and a Glossary

other post with Kirby inking Kirby:

Strange Tale Indeed

Battleground, Jack Kirby’s Return to Atlas

Captain 3D