Nine months separated Black Cat Mystery #57 and Black Cat Mystic #58. Such a lengthy delay would make it difficult for the title to pick up a following of readers. That was bad enough but it would be a further year before Black Cat Mystic #59 hit the stands. What was Harvey thinking? The inking style used by Jack Kirby for BCM #59 does not match very well with his inking found in other publications from 1957 but it is a good match for the inking he did in BCM #58 (Jack Kirby’s Austere Inking, Chapter 8, More Harvey). The original art for one of the stories (“The Great Stone Face”) has a Comic Code approval stamp dated June 1956 which shows that the art was in fact created in 1956. Normally getting the Comic Code approval was the last step before getting ready for the printers which would suggest a planned publication date of October or November 1956. That is just the date that would be expected had Harvey not put the issue on hold. Again what was Harvey thinking? This is not a suggestion that Harvey made a poor decision (although that was true) but a real question on why the apparently sudden change in plans. Poor sales does not seem a likely explanation. Sales figures for BCM #58 would not have been available at the time the decision was made to hold back on BCM #59.

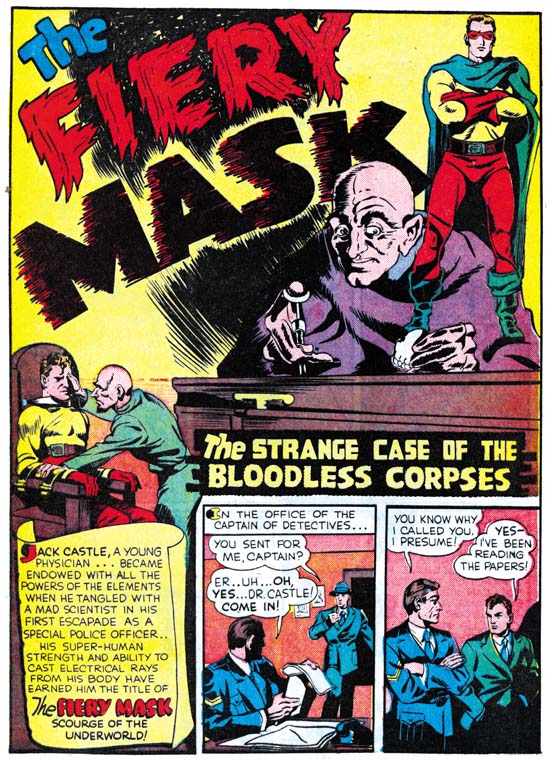

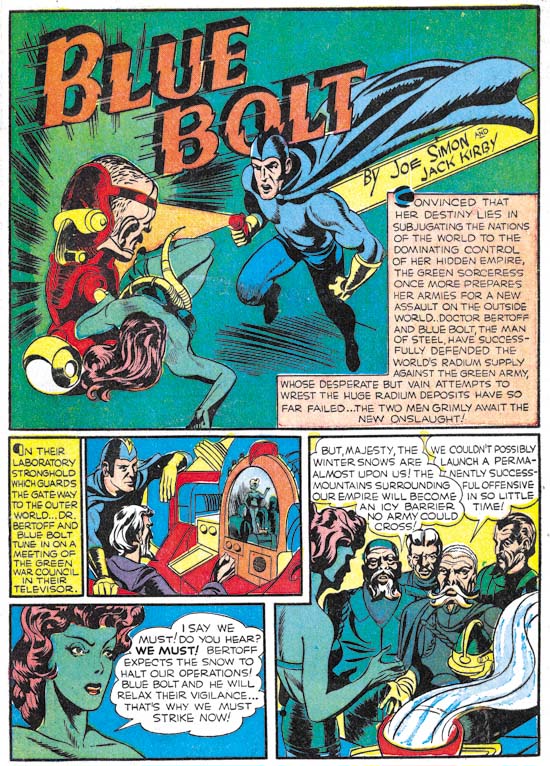

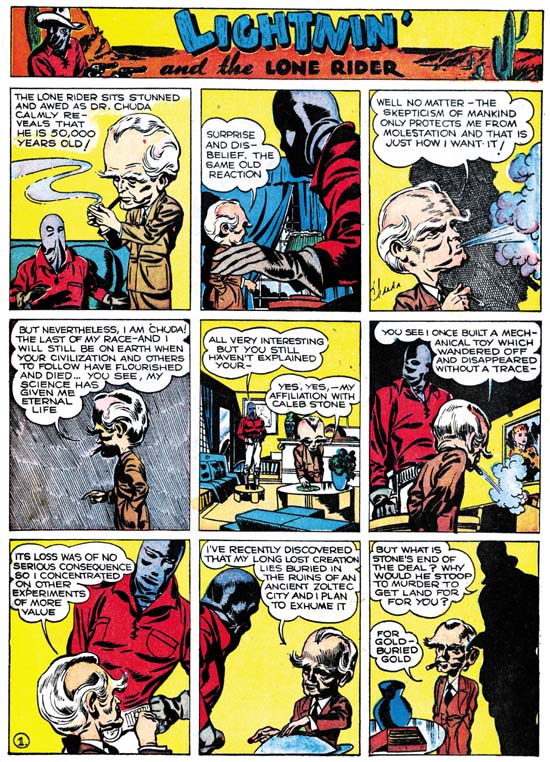

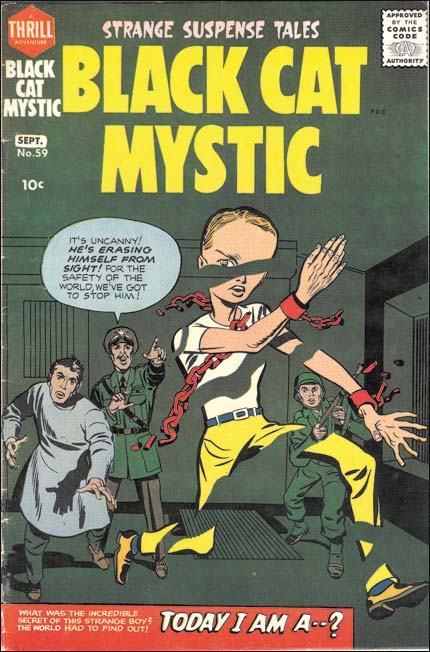

Black Cat Mystic #59 (September 1957), pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

The cover for BCM #59 shows a figure erasing himself away, a rather unusual image to say the least. The figure has six fingers per hand and a large head which indicate he is not truly human. That the figure was also chained indicates that he was considered a threat by the scientist and soldiers shown on the cover.

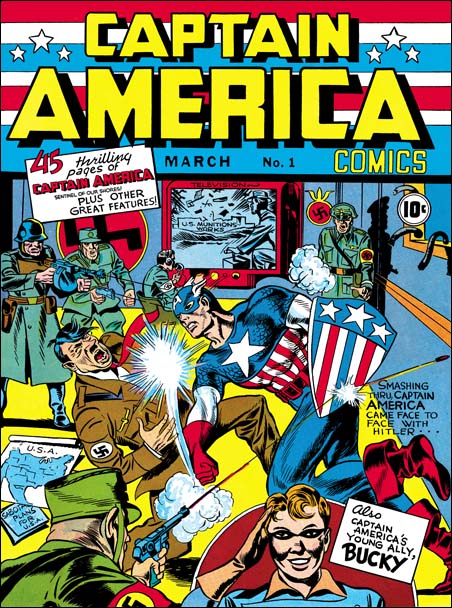

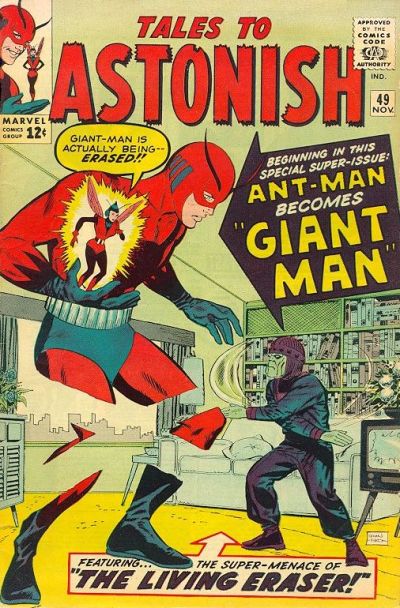

Tales to Astonish #49 (November 1963), pencils and inks by Don Heck (image from GCD)

While by no means identical a similar cover was created years later for Tales to Astonish #49 (November 1963). The cover artist was Don Heck but the story was drawn by Kirby and inked by Heck. Apparently the Living Eraser was for years used as an example of occasional failures by Lee and Kirby collaboration. While the Living Eraser was not up to the standards of comic book antagonists like Galactus he seems better than some of the other early creations such as Paste Pot Pete. At least the Living Eraser provided a memorable image.

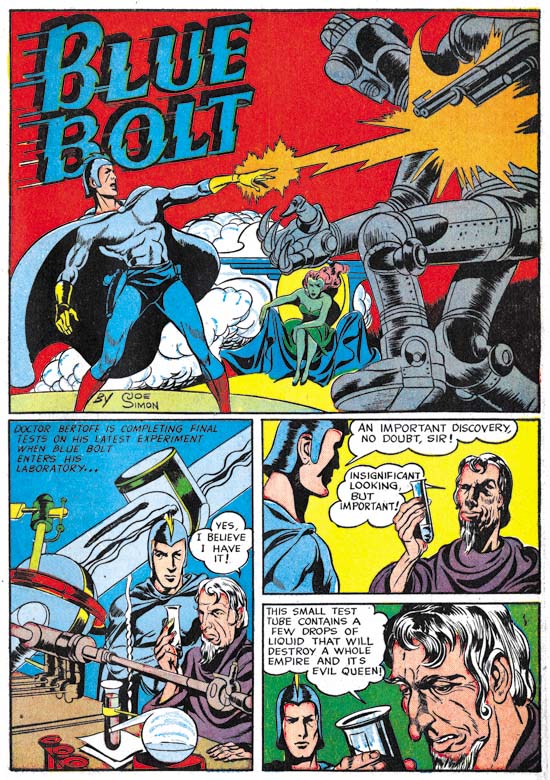

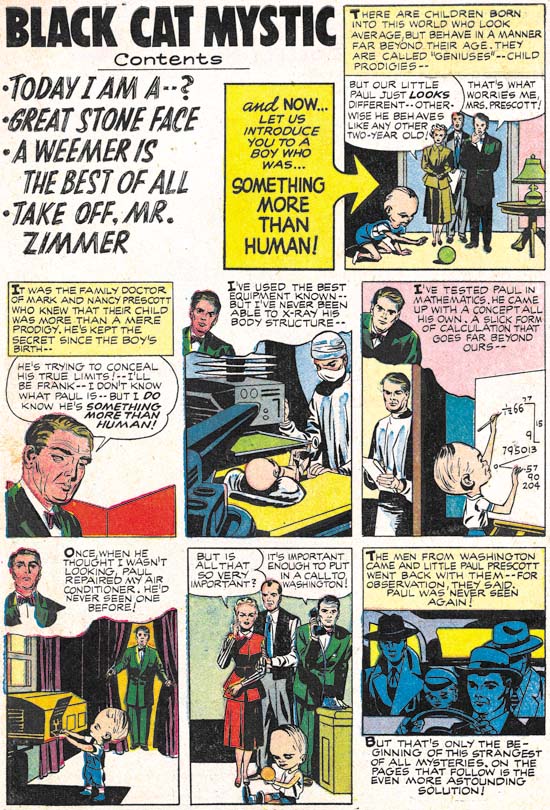

Black Cat Mystic #59 (September 1957) Introduction, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Joe Simon

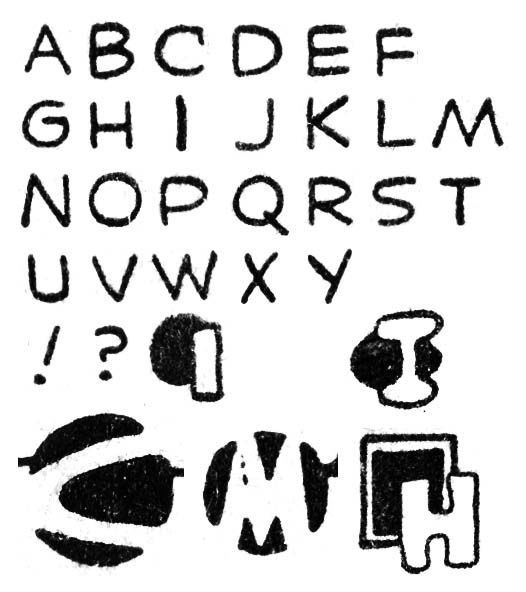

A contents page was pretty much standard at Harvey when Simon began working there as an editor. But it appears to have been Joe that converted the page into an introduction page. This introduction would be a sort of a prequel to one of the stories in the comic. Joe would often try to draw the introduction in the same style as the artist who did the story (Joe Simon’s Turn At Imitating). Joe was good enough of a mimic that some experts still attribute these introduction to the story artist. Jack Kirby also did some introductions for Harvey (Bill Draut and His Imitator, Jack Kirby, Jack Kirby Swiping from Bill Draut, Kirby Imitating John Prentice and Kirby Imitating John Prentice Again). Previously I believed that Jack was imitating the story artist as well. However Kirby was a rather poor imitator and except for one swipe Jack was just being himself. I now realize it was Simon who was purposely inking of these pieces to made them look the story artist. But in the case of the Introduction for BCM #59 Kirby was the story artist and Joe inks the piece in his normal manner.

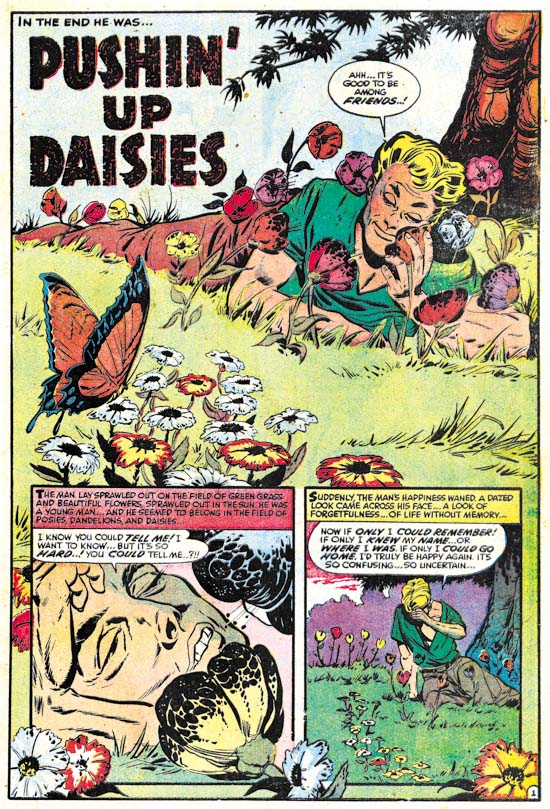

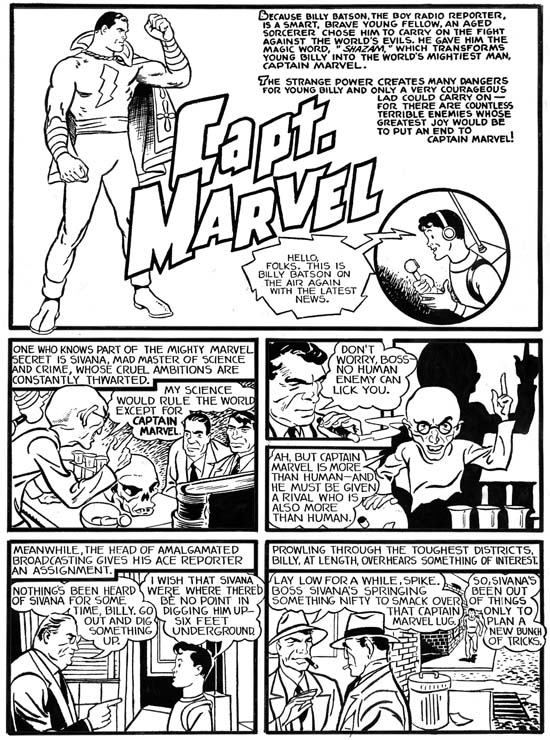

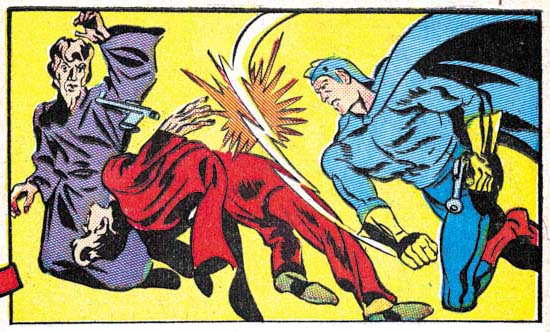

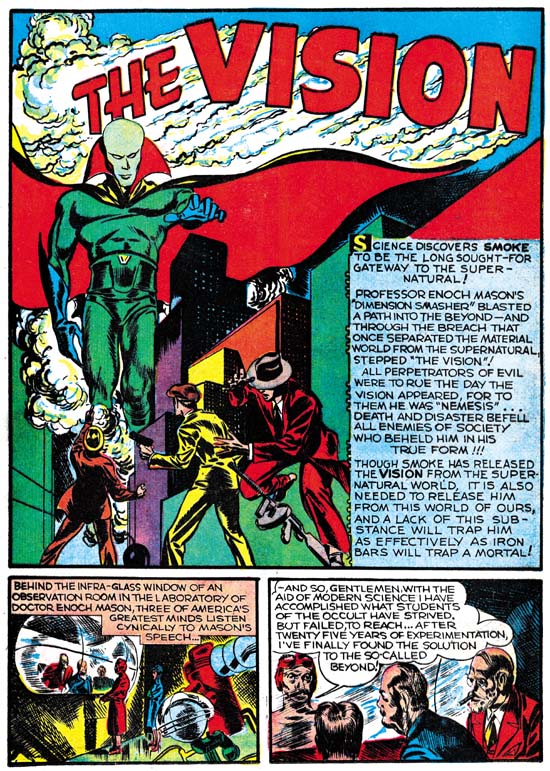

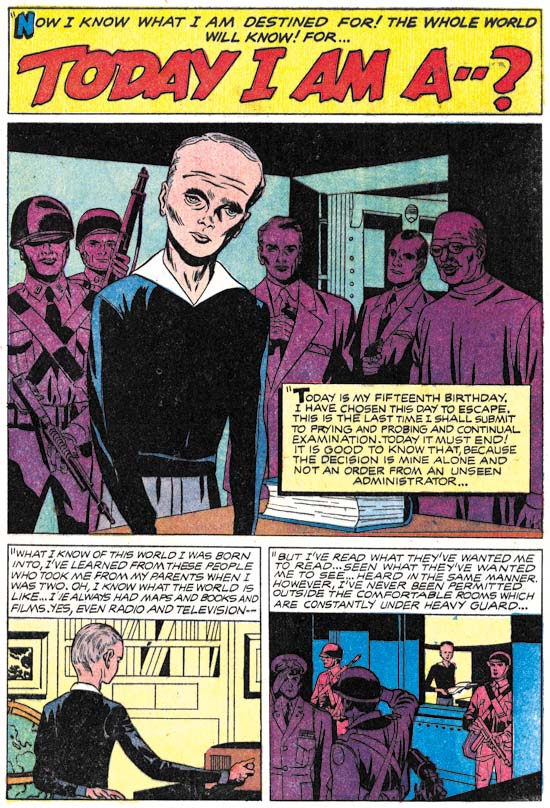

Black Cat Mystic #59 (September 1957) “Today I Am A…”, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Joe Simon

Jack Kirby is famous for his high action comic art. Understandably because he was so good at it. But Kirby was also master at building tension into a story and “Today I Am A…” is a great example of that. In the hands of a lesser artist this might have been a rather mundane story but Jack transforms it with his usual magic. “Today I am a man” is a bar mitzvah cliché that was probably lost to most of the young readers when this story first was published but it is a clever title for a story of an exceptional individual becoming of age.

X-Men #1 (September 1963) “X-Men”, pencils by Jack Kirby, inks by Paul Reinman (image from GCD)

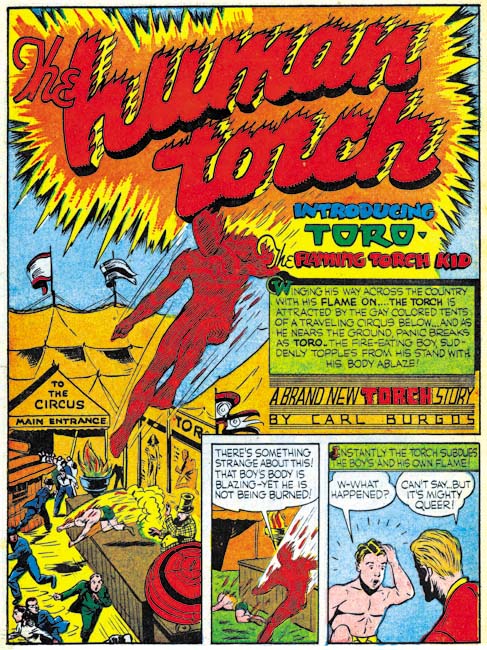

The Introduction and story “Today I Am A…” never mention the word mutant. However despite his physical and mental differences the main character Paul was born of normal parents. He was clearly meant to be a sudden and dramatic stage in the evolution of mankind. Normal humans fear and seek to confine him. I do not think I am out of line to suggest that in this story from BCM #59 we find the concepts that would eventually become Homo superior feared by the rest of humanity that would be the basis for the X-Men created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Some fans object to provided creation credits to Lee and Kirby because of all the individual X-Men that were created by other artists. However it was Lee and Kirby that created the premise of mutants and public mistrust that is the foundation of this series right up to today.

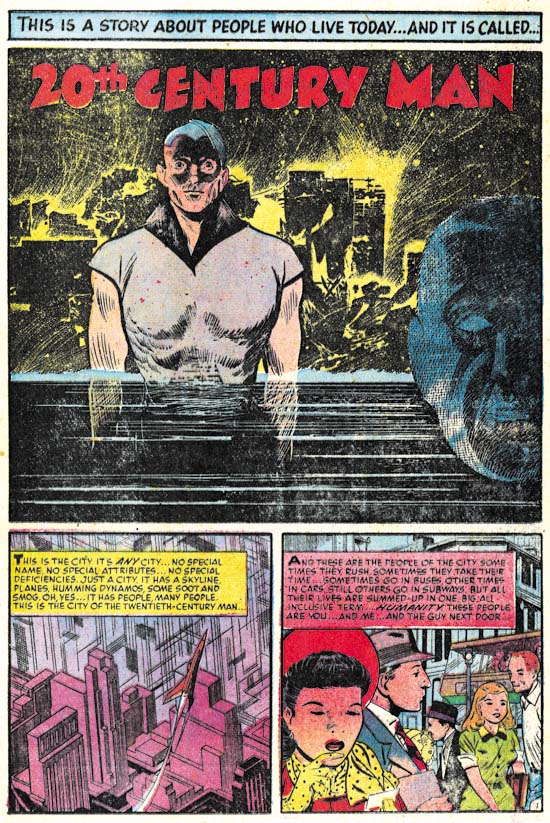

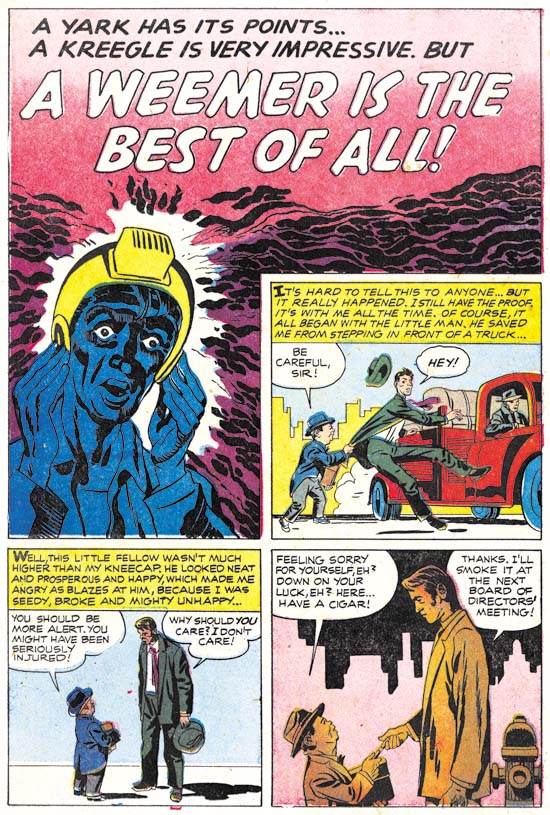

Black Cat Mystic #59 (September 1957) “A Weemer Is the Best of All”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

“A Weemer Is the Best of All” is a story in a more humorous vein. Not side-splitting humor but definitely a story not meant to be taken seriously. Humor was frequently a part of Simon and Kirby’s repertoire. Even action stories often had humorous parts to them.

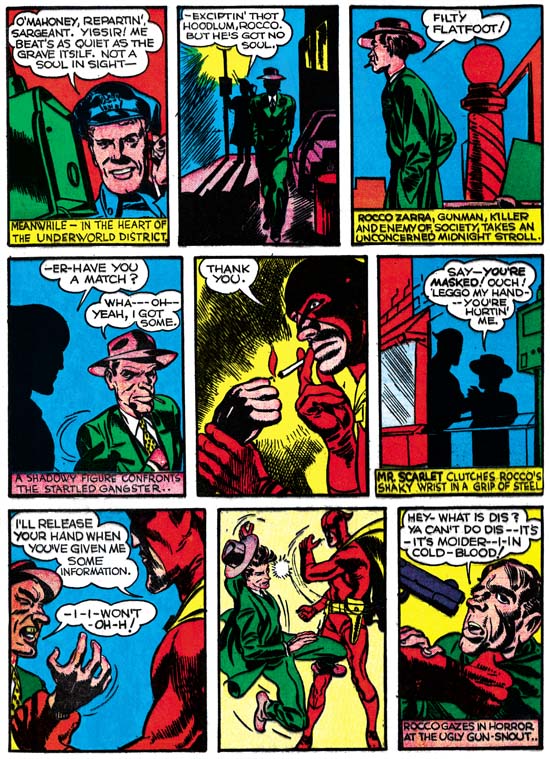

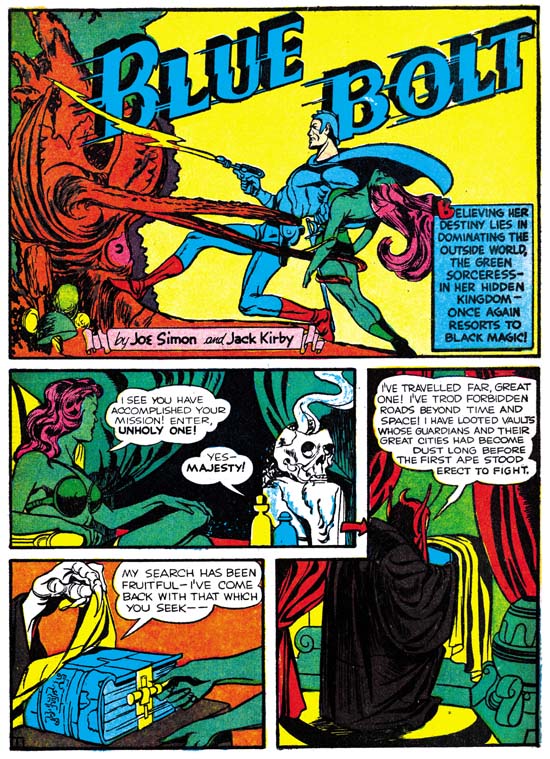

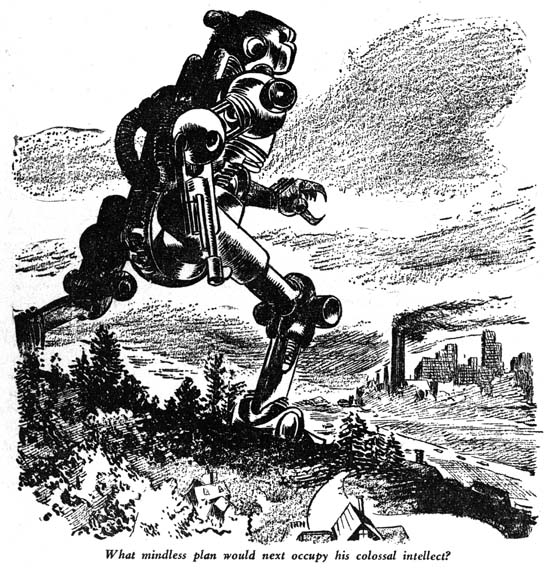

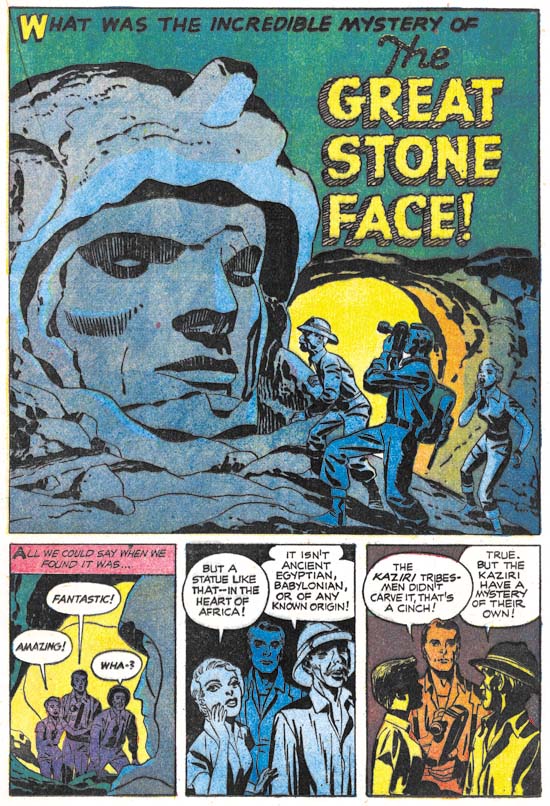

Black Cat Mystic #59 (September 1957) “The Great Stone Face”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

A monumental stone sculpture of unknown origin, an African tribe with technical skills, and a rifle slinging anthropologist. This is one of those stories so imaginative that one wonders where they came up with it. I can understand the anthropologist but where did the rest come from? Both Joe and Jack were science fiction fans and I suspect somewhere in the pulp magazines they read supplied the kernels that eventually formed into stories such as this one.

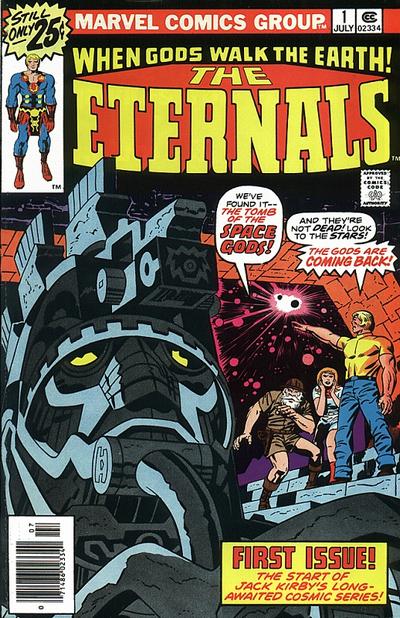

The Eternals #1 (July 1976), pencils by jack Kirby, inks by Frank Giacoia (image from GCD)

The theme of gigantic aliens residing on earth for immense periods of time for mysterious reasons is common to both “The Great Stone Face” and the Eternals (a title Kirby created for Marvel in 1976). Jack would often expand on story lines he worked on earlier in his career.

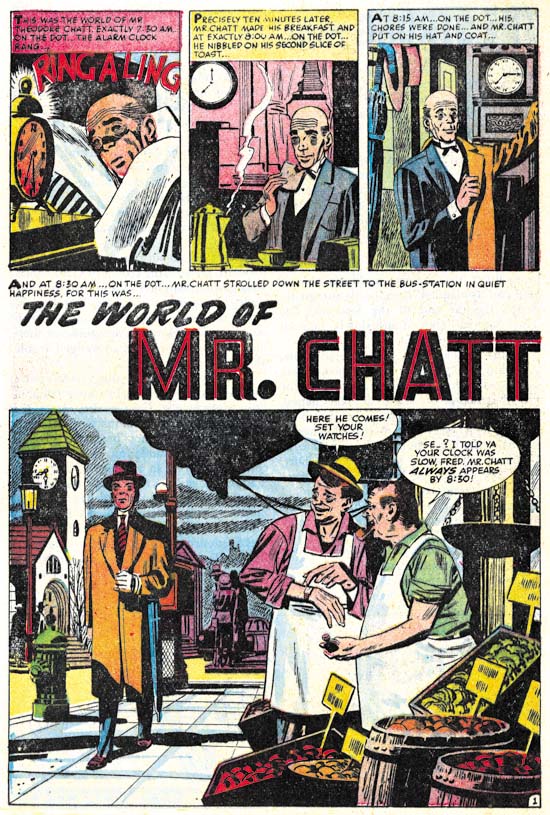

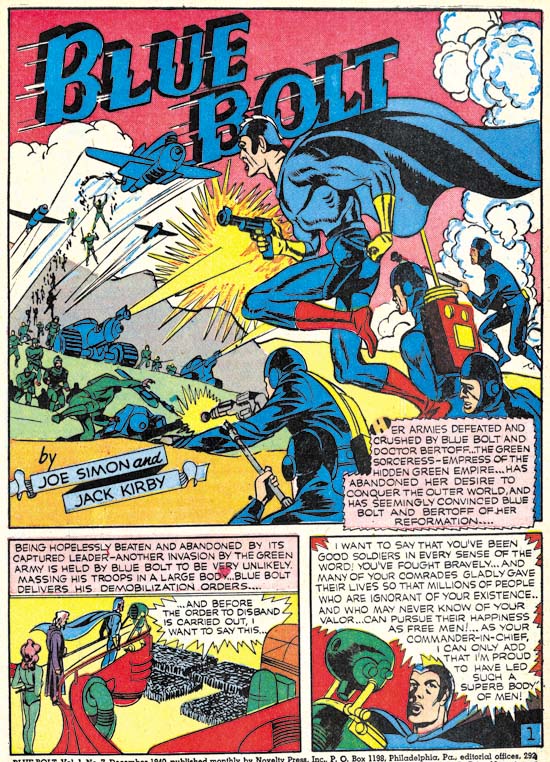

Black Cat Mystic #59 (September 1957) “Take Off, Mr. Zimmer”, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

The ghost Mr. Zimmer was presented in BCM #58 and seems to have been planned as a recurring character. In BCM #58 Mr. Zimmer was presented in the first, featured, story. However in BCM #59 Mr. Zimmer became delegated to the final story in the book. While the title Black Cat Mystic would suggest the horror genre the contents were predominately science fiction. So perhaps Mr. Zimmer fall from grace was just a recognition that he was somewhat out of place in the direction the title had gone. But then again horror, although a rather mild version suitable for the Comic Code, would continue to play a roll in the title. In any case this would the last appearance of Mr. Zimmer.