Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) Jumbo, the mascot

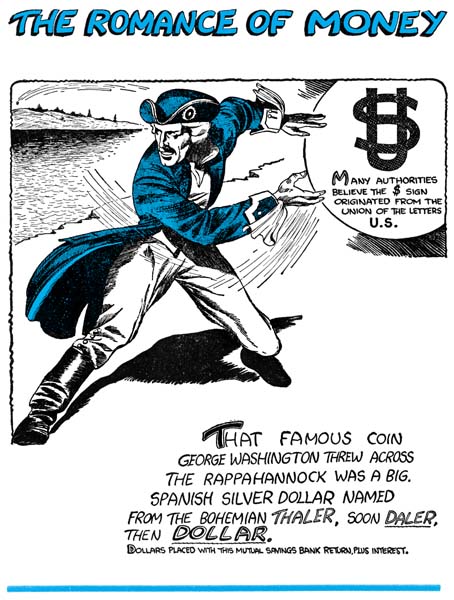

Will Eisner and Jerry Iger teamed up in 1936 or 1937 to become one of the first studios to provide complete comic book packages to publishers. Previously comic books were largely reprint compilations of newspaper syndication strips. Years later Will Eisner said that he believed there would not be enough syndications material available to meet the rising demand for comic books and so there would be a market for new material created specifically for comic books. That may have been true but one of Eisner and Iger’s packages Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) published by Fiction House was actually composed of syndication strips. I have no idea on how many of the strips from Jumbo Comics #1 had previously appeared in newspapers but at least some of them had been printed in the British magazine Wags. Others may have truly been new creations but in a format showed that they were meant for syndication strips.

Jumbo Comics certainly lived up to its name as it was printed in what is called tabloid size (10.5 by 14.25 inches). Except for the cover, no color was used. Perhaps to compensate for the lack of color, the paper used came in two tones; one the normal “white” and the other dyed a pinkish color. (I have removed the page color from all images presented in this post.) All pages followed the same format. There would be a title panel that would normally occupy the entire top of the page although sometimes a single story panel might be included. Below would be three or four rows of panels with three panels per row (occasionally two panels would be combined to form a longer one). While there would be three or four pages provided for each title, all pages would have the same format including the title.

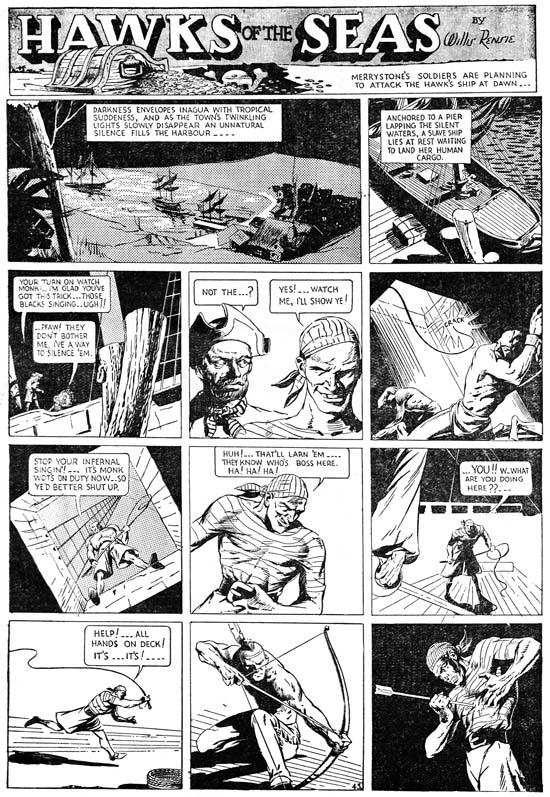

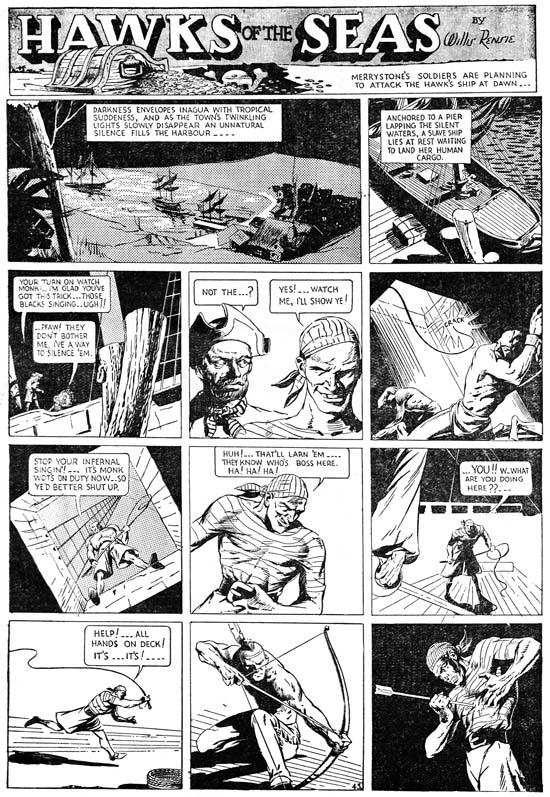

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “Hawks of the Sea” by Will Eisner

Will Eisner was very conscious about the small size of his operation. While Eisner was involved in many aspects in the making of the strips found in Jumbo Comics but, his name appears on none of them. However, in the title “Hawks of the Sea” is credited to Willis Rensie; Rensie is Eisner spell backwards. This is years before his famous work on the Spirit, but here Eisner is already an accomplished comic artist. Note Eisner’s dramatic use of sifting perspective. As we will see, a number of the artists appearing in Jumbo Comics who would later achieve great fame but none of them supplied art at that time with quite the quality as found in “Hawks of the Sea”.

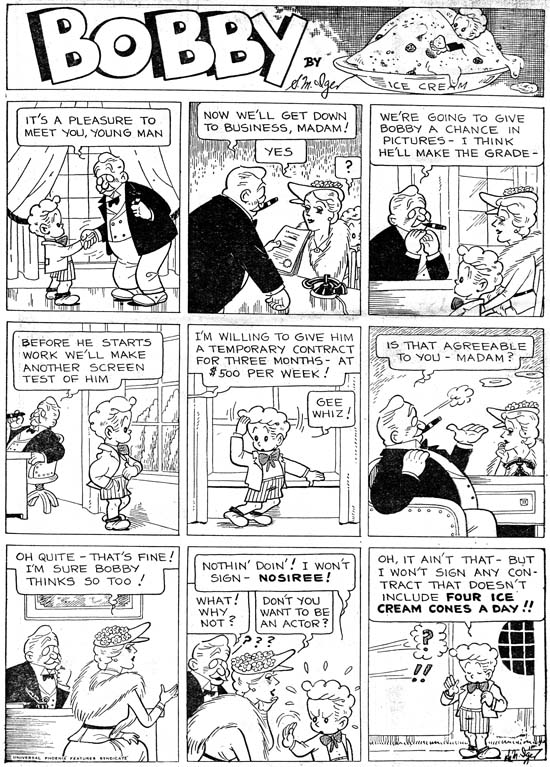

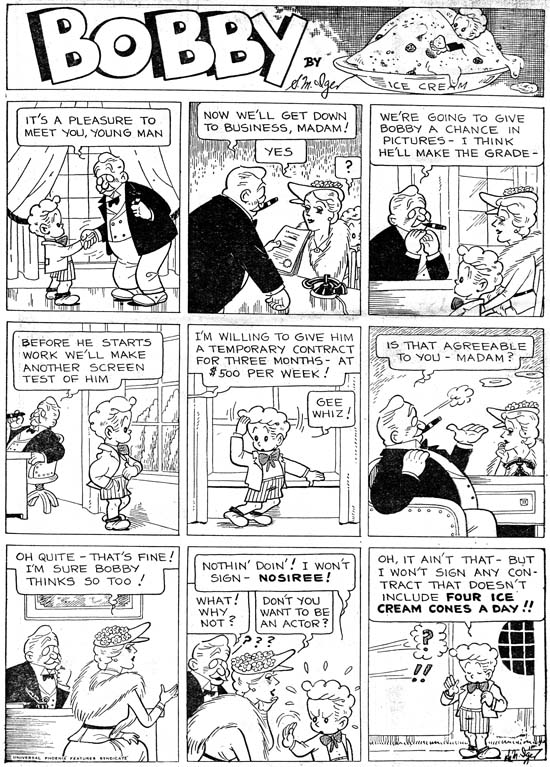

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “Bobby” by Jerry Iger

“Bobby” is credited to S. M. Iger, but surely that must be an alias for Jerry Iger. Iger was supposed to have been the salesman of the Eisner & Iger partnership, but here he shows how talented artist he was as well. Or it would if we can be sure that this piece was actually done by Jerry. In an interview (The Jack Kirby Collector #16) Eisner said that Iger was not a good artist but he could letter. Was this sour grapes about a former partner or realistic evaluation? I have no way of knowing. It all depends on whether “Bobby” was really done by Iger.

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “Peter Pupp” by Bob Kane

Bob Kane was a high school friend of Will Eisner, so his presence in Jumbo Comics is not surprising. Batman did not debut until May 1939 so Kane almost certainly did not yet have his studio of ghost artists that he became famous for in later years. I have always found the earliest Batman art, presumably done by Kane, as stiff and rather unappealing. Because of that “Peter Pupp” is quite a surprise. Granted it is of the funny animal and not the hero genre but it shows a suppleness totally absent from Batman. Mickey Mouse would seem to be an obvious inspiration for this strip. I particularly find amusing how the villain’s minion sports Mickey Mouse ears.

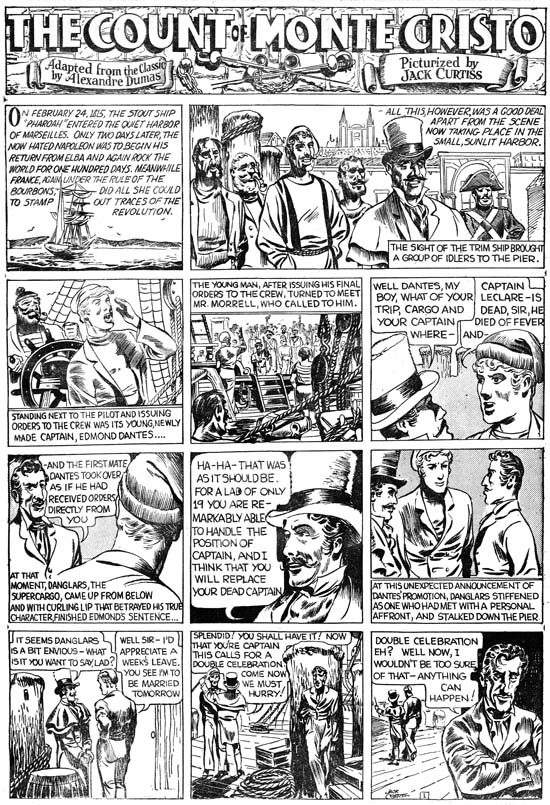

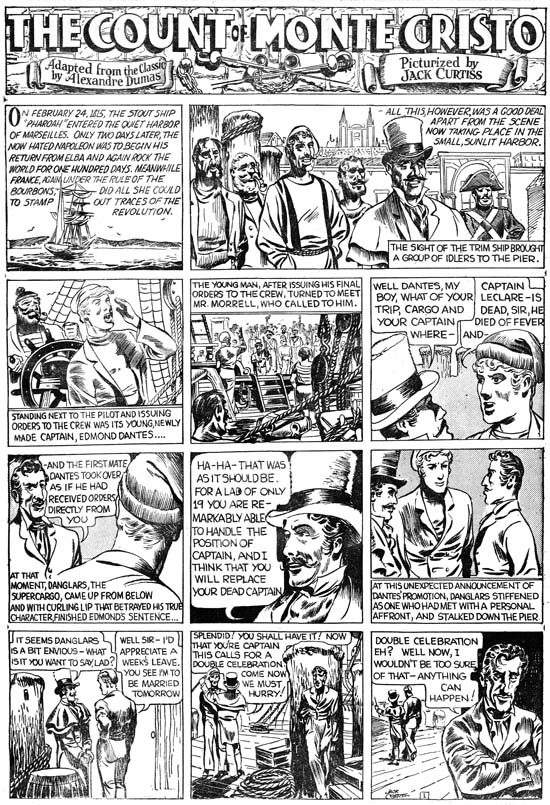

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “The Count of Monte Cristo” by Jack Kirby

Jack Kirby has said that his first published comic book work be for Wild Boy Magazine, although I do not believe anyone has been able to confirm that. The earliest work that can be confirmed is probably “The Count of Monte Cristo” which appeared in the British magazine Wags in March 1938. These Kirby strips were used again in Jumbo Comics #1. The name Jack Kirby was one he adopted later while his birth name was Jacob Kurtzberg but in this strip he signed his name as Jack Curtiss. By any name this was a far cry from the work Jack would do in just a few years. Even though Kirby’s art would progress much further, his art in Jumbo Comics shows that he already was a very gifted artist, better then most of his peers.

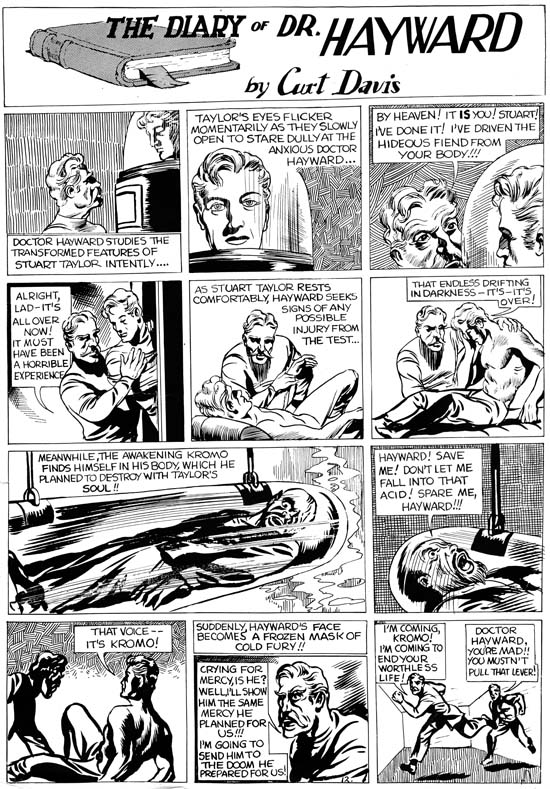

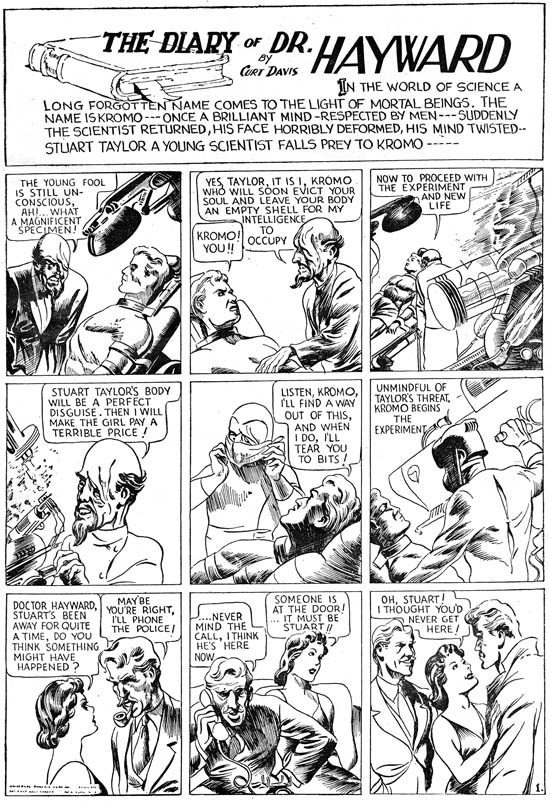

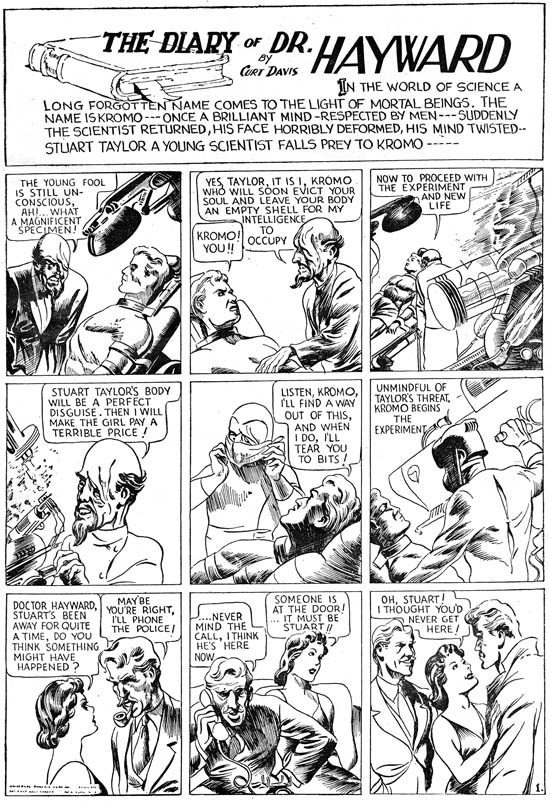

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “The Diary of Dr. Hayward” by Jack Kirby

Jack also drew “The Diary of Dr. Hayward” this time under the name Curt Davis. While “The Count of Monte Cristo” was based on the book by Alenandre Dumas, the Dr. Hayward strip was all new writing. It is hard to be sure, but the plot seems to be similar to those Jack would write later and so I credit the scripting here to Kirby as well. Without the classic trappings of “The Count of Montet Cristo”, Jack seems quite comfortable both in art and script with the more science fiction story of Dr. Hayward. A handsome hero, a mad scientist and body switching it all provides a setting for a morality tale about good versus evil.

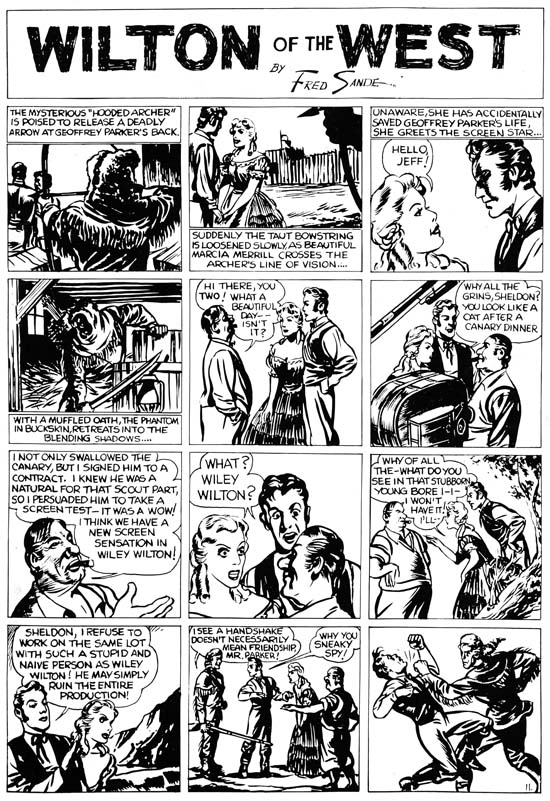

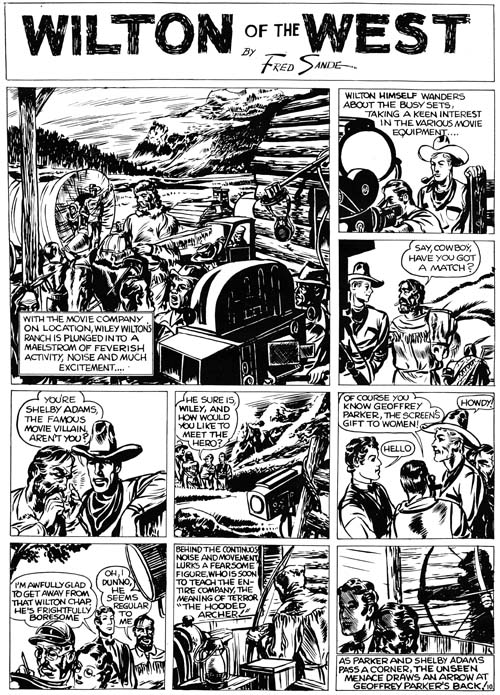

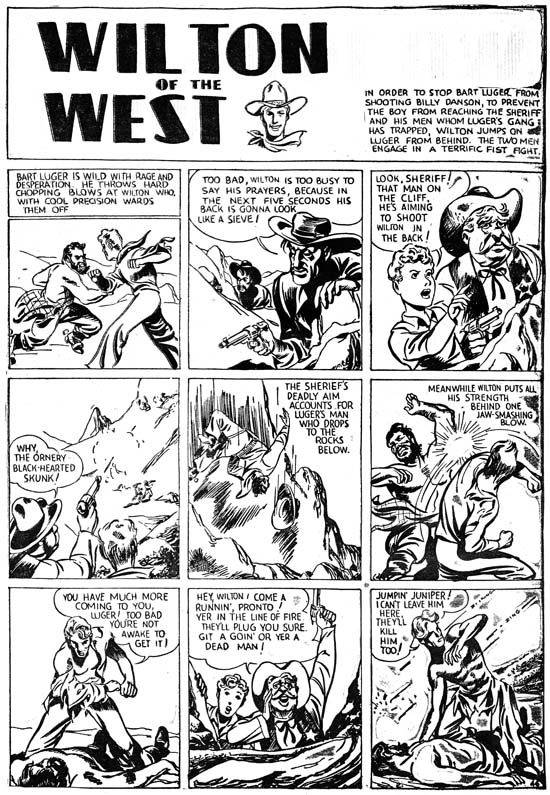

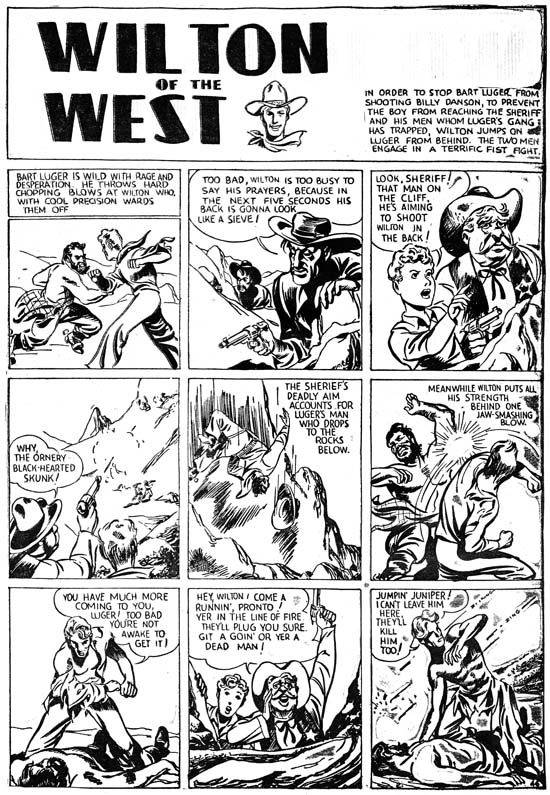

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “Wilton of the West” by Jack Kirby

It would seem two strips were not enough for the already prolific Kirby as he did a western as well but this time without signing it. It is here that we can see that while Kirby had a way to go before he reached his full potential, he already had developed his predilection for slugfests. The smashing blow depicted in panel 6 is done in a manner far from his signature style but it still embodies Kirby’s enthusiasm. He may not have mastered his use of exaggerated perspective but look how Jack has in panel 7 the hero bend at the torso while thrusting his face forward so that no neck is seen. It is the beginnings of a pose that would become Jack’s trademark.

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “Sheena Queen of the Jungle” by Mort Meskin

Of all the strips present in Jumbo Comics, the most enduring was “Sheena Queen of the Jungle”. It would eventually dominate the long running Jumbo Comic (1938 to 1953) as well as achieving its own title. Sheena even became a television show (1955) and a movie (1984). The title block credits Sheena to W. Morgan Thomas but this was just one of the pseudonyms adopted by Will Eisner to hide the small size of his studio staff. For the Sheena strips in the Jumbo Comics the artist was Mort Meskin as can be seen by the signature in the final panel. This is the earliest published work by Meskin that I am aware of. While not as polished as Will Eisner or Jack Kirby, Mort’s art already has an energy to it. Look how he composes the figures of the armed natives in panel 6 all on the left side of the panel and on the right in panel 8. Over and over in these strips you can see Meskin’s concerns about how to graphically tell a story. It may be the start of his professional career, but Mort already had his own unique vision.

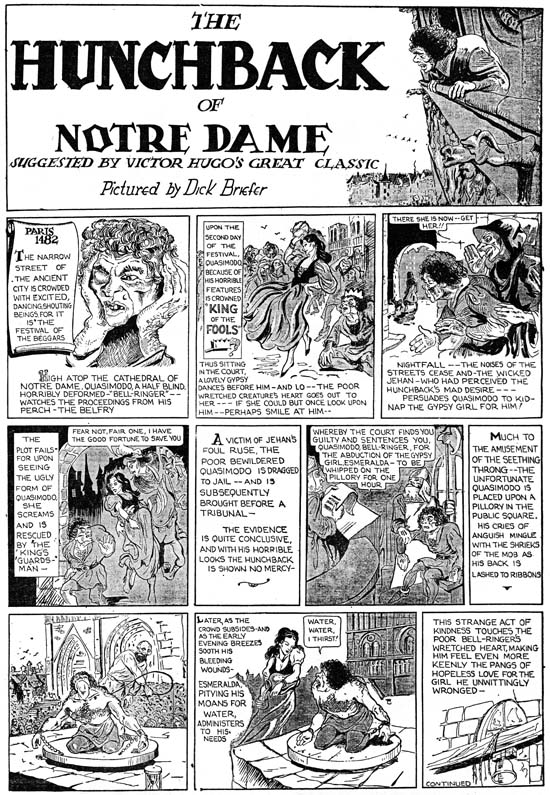

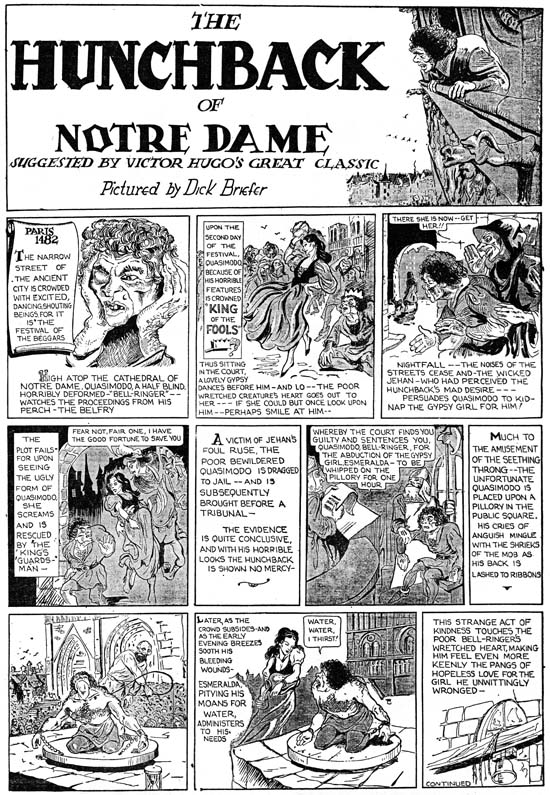

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” by Dick Briefer

It is hard to recognize some of the artists appearing in Jumbo Comics when you are only familiar with their later work. This is especially true with the first strip of “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” by Dick Briefer. What makes this particular strip so unlike some familiar work by Briefer is mainly the detailed pen work so different from the simpler and more fluid inking found much later in Briefer’s Frankenstein. One thing to note is that while the other artists reviewed in this post had adopted a very grid-like panel layout, Dick’s use of caption boxes and panels breaks from that familiar rigid pattern.

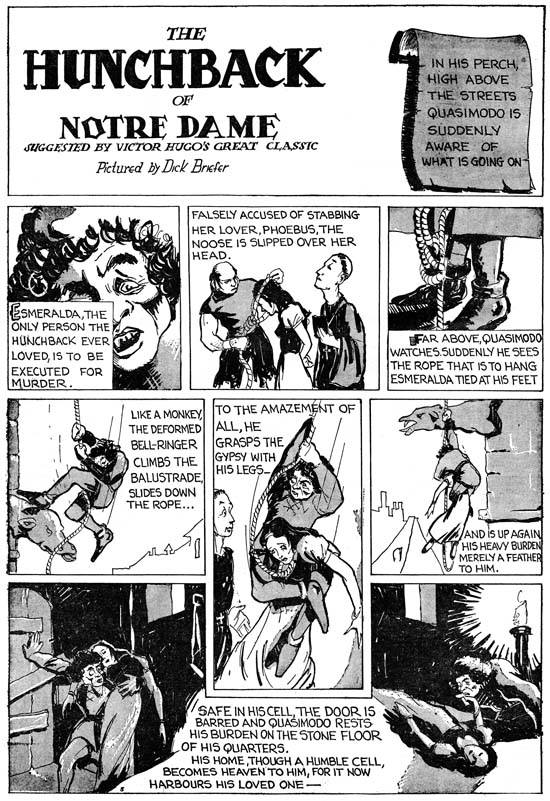

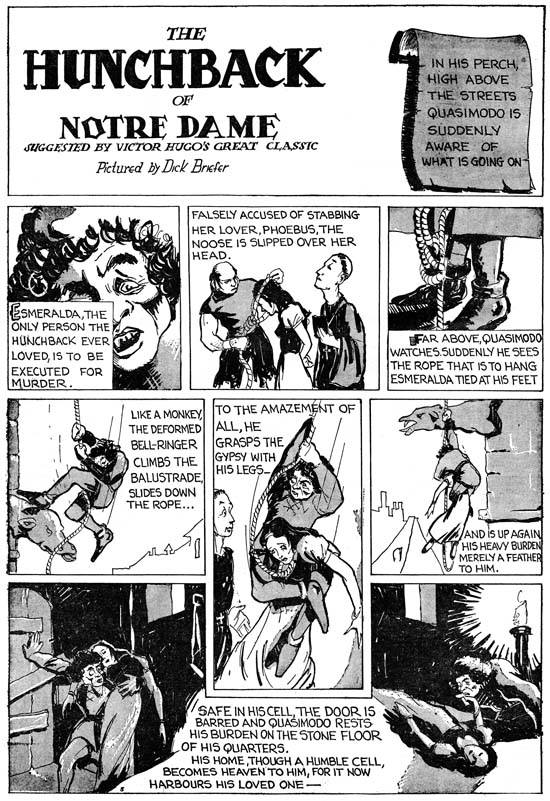

Jumbo Comics #1 (September 1938) “The Hunchback of Notre Dame” by Dick Briefer

The fine inking was abandoned immediately after the first strip and the results make it much easier to recognize Briefer’s participation. I choose to use the fifth strip but in terms of technique it does not differ from the second. But what a great page! While Dick is no longer using the same captions he still deviates from a grid panel layout. Note how the fifth panel was extended vertically down into and how the last panel really is two panels in the same boarder separated by a caption.

There are other strips in Jumbo Comics #1 done by talented artists that are unsigned. Considering the pretenses Eisner maintained of a larger shop there is a good possibility that they some were made by Eisner himself deceptively adopting another style. Or perhaps assigning the finishing or inking to a different artist. I am sure Eisner provided direction to all the artists working for him but I am just as certain that did not include laying out the art. Each of the artists reviewed here had their own unique manner of graphically telling the story which would not have been true if they were working from layouts. It is amazing to see so much talent, albeit in its earliest flowering, in one comic book. Jack Kirby would be also included in Jumbo Comics #2 and #3 for his work on “The Diary of Dr. Hayward” and “Wilton of the West”. Mort Meskin would work on “Sheena Queen of the Jungle” even longer (at least until issue #5). Bob Kane and Dick Briefer would also make further appearances. Eventually Jumbo Comics would abandon its oversize format and adopt a more standard comic book content but for a while it was a most unusual comic book.