In a recent post I showed that data suggested that the cause of the decline of comics in the mid 50’s could be attributed to the effects of Fredric Wertham’s book “Seduction of the Innocent” (1954). This issue is of importance not only to the history of comics in general but also to the break up of the Simon and Kirby collaboration. I had also previously reviewed David Hajdu’s book “The Ten Cent Plague” which traced the history of the anti-comic campaign. Historical books are important but I also felt that a reading of the seminal “Seduction of the Innocent” itself was in order.

I really had no idea what to expect. Of course I knew about how down right silly some of his conclusions sounded such as that Batman and Robin projected a homosexual relationship. I had also understood from second hand sources that Wertham really did not have scientific evidence to backup his claim about the link between comic books and juvenile delinquency. But the whole idea of reading this book was to allow Wertham to in effect plead his own case and so I tried to keep an open mind while I read it.

As I said I really did not know what to expect but I never thought I would find this book so poorly written. Wertham was a psychiatrist some of whose writings were included in medical and scholarly journals. I knew that “Seduction of the Innocent” was written for the general public but I still expected a well ordered and reasoned presentation. Instead I found it filled with histrionics and that Wertham’s train of thought seemed to wander erratically. There was an overall structure provided by the chapters but within a paragraph it could frequently seem like a stream of consciousness. Let me provide an example paragraph (pages 33 and 34):

This Superman-Batman-Wonder Woman group is a special form of crime comics. The gun advertisements are elaborate and realistic. In one story a foreign-looking scientist starts a green-shirt movement. Several boys told me that they thought he looked like Einstein. No person and no democratic agency can stop him. In requires the female superman, Wonder Woman. One picture shows the scientist addressing a public meeting:

“So my fellow Americans, it is time to give America back to Americans! Don’t let foreigners take your jobs!”

Admittedly this is a particularly egregious example in that each sentence seems to take the reader in a different direction. However disjointed paragraphs are found in great abundance throughout the book. As for the histrionics here is an example of the extremes he could go (pages 95 and 96):

What in a few words is the essential ethical teaching of crime comics for children? I find it well and accurately summarized in this brief quotation:

It is not a question of right, but of winning. Close your heart against compassion. Brutality does it. The stronger is in the right. Greatest hardness. Follow your opponent till he is crushed.

These words were the instructions given on August 22, 1939, by a superman in his home in Berchtesgaden to his generals, to serve as guiding lines for the treatment of the population in the impending war on Poland.

Literary criticism aside, what matters most is what points was Wertham trying to make, how well did he support his arguments and how creditable was he? My summary of the primary views found in “Seduction of the Innocent” would be:

- Comic books promote violence and crime in children.

- Comic books promote racism.

- Comic book can lead to impaired reading ability.

- Comic books desensitize their readers to good literature.

I am not saying these were the only issues but I feel they were the most important. For instance Wertham does raise the concern that romance comics may adversely affect sexual morals. But that occupies only a small portion of his writing and he seems much more concerned that the types of violence shown in comics toward women may lead readers to become sexually aberrant.

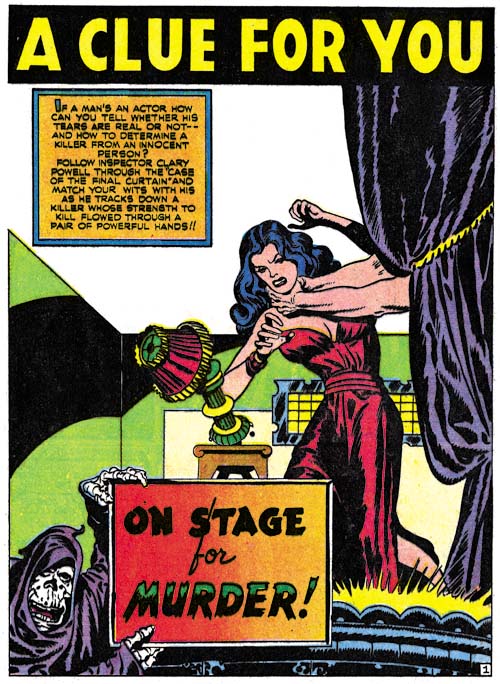

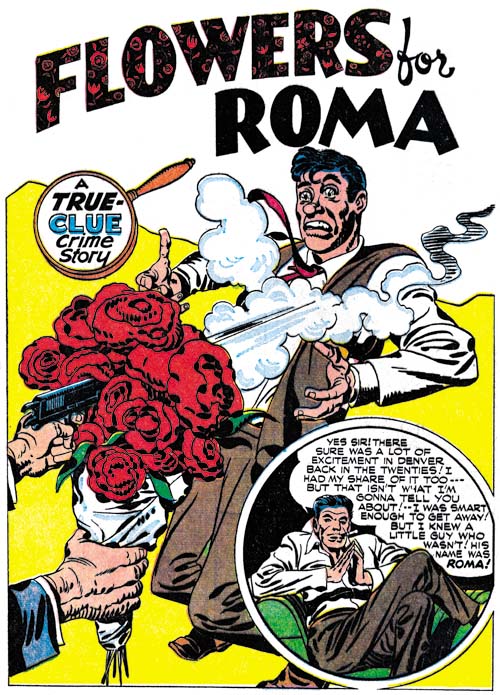

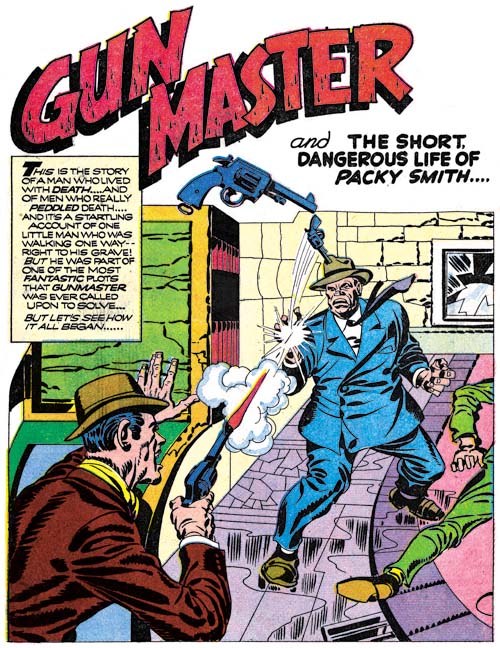

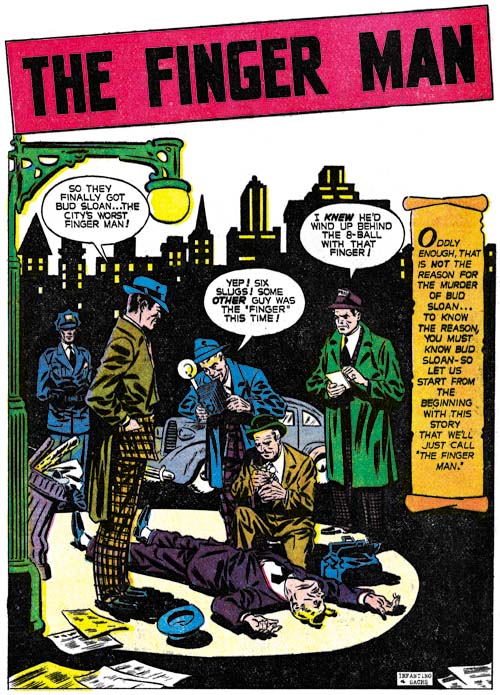

Undoubtedly for Wertham the most important criticism against comic books was the first, the connection between comic books and juvenile delinquency. Wertham believed that crime comic books promoted the criminals as the real heroes of their stories. That in particular the violence portrayed in the stories influenced the behavior of many youngsters. Further that crime comics gave instructions on how to actually commit crimes. Also that advertisements found in comics even provided the source from which youngsters could obtain weapons. Wertham’s classification of comics was not the same as commonly used today. For Wertham the crime comics also included westerns and superheroes. Any story that included a crime would be classified as a crime comic. For other reasons Wertham also criticized romance and horror comics as well. “Seduction of the Innocent” was not just a critique of comic books it was also a call for legislation action to ban all objectionable comics. As far as I can tell no category of comics completely escaped Wertham’s wrath. He even had complaints about some from the funny animal genre.

Wertham’s charges against comics were serious and, if true, a justifiable cause for action. So where did Wertham get the evidence to support his claims? Wertham placed much emphasis on his clinical studies. Wertham was a psychiatrist who did work in various clinics and hospitals. He also worked with children caught and subjected to the legal system. Wertham felt that clinical studies were the best method to determine the underlying reasons for the problems suffered by children and he was very critical of other study techniques. Another much used source of evidence could be considered as part of his clinical studies. It was the Hookey Club. This was something akin to group therapy where various children were brought together to discuss the individual member’s problems and come up with suggestions to help. The Hookey club acted as a sort of judge and jury and so it might be considered distinct from a more typical therapy group. Wertham would be present as well but he makes it sound like his actual participation was limited. The final important source of evidence was a study of the comics themselves.

So how creditable was Wertham’s arguments and, most importantly, his evidence? Although Wertham spends some pages describing various means of testing children (such as Rorschach Test) he does not explain how they were used to address the supposed connection between comic books and juvenile crime. Nor does he explain precisely what he means by clinical studies. Perhaps this lack is understandable in a publication for the general public However he does not supply any references for papers on the subject that he had written for some technical journal. As far as I have been able to determine Wertham never published any articles on his study of the comic book and juvenile delinquency in any journal of psychiatry or psychology. This is troublesome because while I might not understand his research methods well enough, I am also unable to see how his peers felt about his methodology either. In the end Wertham only has his authority as an expert to support his claim that his clinic studies prove the connection between comic books and juvenile delinquency. It bothered me while I was reading this book that time and time again when writing about others who disagreed with his findings Wertham would call for the scientific evidence that supported his critic’s position. Yet Wertham never truly supplied the evidence to back up his own claims.

Now I am far from an expert in Wertham’s field but I am going to hazard some observations nonetheless. I believe that what Wertham calls clinical studies is the understandings that he gained while treating patients. Now this might not be a bad approach for studying physical illnesses but for me it poses serious issues when it comes to mental problems. Treatment of mental problems does not go in one direction. It is not the patient supplying all the information nor is it the doctor doing the treatment based on his examination alone. Both the patient and the doctor take part in the process. With such give and take between the patient and the doctor how is it possible to be certain what is learned from the patient and what comes from the doctor’s preconceived notions? This does not seem like an objective methodology to me.

This concerns me because the comments that he reports coming from young patients often sound suspiciously like Wertham’s own views. I find the following statement by a member of the Hookey Club particularly suspicious (page 71):

You don’t have to think of it, it is in the back of your mind, in your subconscious mind.

May be I am wrong, but talking about “subconscious mind” does not sound like the terms that a youngster would normally use to me. This suggests that Wertham was more then just an observer at the meetings of the Hookey Club. If Wertham had influenced the Hookey Club in this way what other statements by Hookey Club members might what have actually been influenced by Wertham? Here is another example (page 192):

Like many other homoerotically inclined children, he was a special devotee of Batman: “Sometimes I read them over and over again. They show off a lot. I don’t remember Batman’s name…”

How creditable is it that someone who really so wrapped up in Batman would not remember his secret identity? More probable is that this member really was not that much of a fan but was saying what he thought Wertham wanted to hear.

The other area of evidence that Wertham used was from the comics themselves. Wertham said he made a careful and detailed study of comics and berated his critics for not having done so. Unfortunately Wertham frequently cited information about comics without identifying what comics the information was based on. This makes verifying some of his statements difficult if not impossible. And I do wonder how careful his studies of comic books were. For instance (page 106):

“You know,” the boy said, “what I really like is the Blue Beetle [a figure in a very violent crime comic book]. I read that many times. That’s what I dreamed about. I don’t have it at home; I get it at another boy’s house.”

“Who is the Blue Beetle?”

“He is like Superman. He is a beetle, but he changes into Superman and afterwards he changes into a beetle again. When he’s Superman he knocks them out. Superman knocks them out with his fist. They fall down on the floor.”

“If you say it is like Superman, how do you know it is?”

“I read the Superman stories. He catches them. Superman knocks the guys out.”

It is not difficult to understand that a child stimulated to fantasies about violent and sadistic adventures and about a man who changes into an insect gets frightened. Kafka for the kiddies!

But the boy’s description of the Blue Beetle turning back into a real beetle is completely inaccurate. Sure it is a child’s mistake but Wertham acceptance of it indicates he really was not that familiar with the character and therefore casts doubt as to how thorough his study of the original comic books was. Here is another (page 257):

This I am told has something to do with the Post Office regulations according to which they may change the name but must keep the number, to keep some sort of connection with the former product. So Crime may become Love; Outer Space, the Jungle; Perfect Crime, War; Romance, Science Fiction; Young Love, Horror; while the numbers remain consecutive.

Wertham’s book was published his book in 1954 at which time Young Love was still a running comic and one that never changed its name to Horror as he claims. If Wertham is so loose with his facts when trying to make this unimportant point how can he be trusted about other claims he makes about the actual comic books?

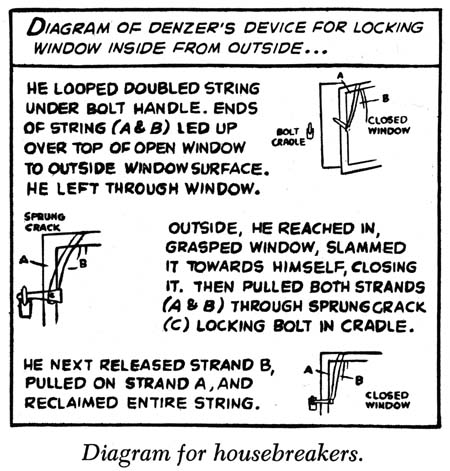

Wertham repeatedly claims that comic books provide instructions to youngsters on how to commit crimes. Note how the above comic book image taken from his book is titled by Wertham “Diagram for housebreakers”. Is it really? A careful reading shows that without a doubt it is showing how to lock a window not how to break in. As usual Wertham does not supply what comic he got this from. However I am pretty certain that this panel was from a murder mystery. The story would have been about a dead victim that had been found in a locked room; a not too uncommon plot device and not just found in comic books. The diagram would have been used at the end of the story to explain how the murder managed exit the room while leaving it locked. This technique would have been of no help to anyone wanting to commit breaking and entry.

Having finished “Seduction of the Innocent” I cannot help but wonder about the postscript. The Comic Code Authority completely changed comics. Crime comics did not last long. Horror comics became so innocuous that it seems strange to apply that name to them. I wonder what Wertham felt about the Comic Code? I suspect he was not happy. I believe that he wanted the elimination of all violence from comics and would have not approved of even the mild form that remained. That Superman could continue would probably been enough for Wertham to condemn the Code. Wertham believed that characters like Superman advanced racism and supported an almost fascist like view.

I also wonder what he would have felt about television. At the end of “Seduction of the Innocent” he does discuss the then new media. After his complete condemnation of comic books, it is surprising to read his glowing opinion of TV. Not that he thought it did not problems, but like so many other things he blamed that on the influence of comic books. Wertham felt that if that comic book influence could be removed that television would have a great positive affect. It must have been a bitter disappointment that after the Comic Code television did not flower as he predicted.

In summary there is reason to question what Wertham wrote in “Seduction of the Innocent”. My reading of this book leads me to my own prognosis of Wertham himself. I have full confidence in the intelligence of my readers and so I have no doubt that all will understand the technical term that should be applied to Wertham. He was a quack. There is no question that “Seduction of the Innocent” had a great impact at the time it was released. I just do not understand why. It got lots of reviews but did anybody actually read it? This book is so seriously and obviously flawed I am amazed that people were taken in by it. I can only surmise that people were so impressed by Wertham’s credentials that they were willing to believe what he had to say based on his authority as an expert.

Fortunately Fredric Wertham’s “Seduction of the Innocent” has become nothing more then a cautionary footnote in the pages of history. Wertham is fully discredited even by those who do not share my view that he was responsible for the decline of comic books. Or is he? Next on my reading list is “Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture” by Bart Beaty (2005). My understanding is that this book attempts to restore Wertham’s image. I am sure I will have something to write about when I have finished that book.