The organizers of the New York Comic Con seemed to have learned some lessons from their previous shows which frankly had problems with crowd control. This year they had an indoor area for the waiting line and entry to the show was a lot quicker. I hope the organizers continue to make improvements but happily they seemed to have overcome the disasters of the earlier years. I was aiding Joe Simon on both Friday and Saturday; largely I just helping to get him to and from the show, others gave him a hand at his appearances. While I give the organizer’s praise for the improvements to the show in general, they are still sadly lacking in support for guests like Joe. Joe is healthy but at 94 not that strong. The distance between the VIP desk and the panel area was way too far. Joe is too proud to use a wheelchair so he did walk it but there really needs to be a better way to do it, perhaps some sort of go-cart. Leaving the show on the second day was difficult as well.

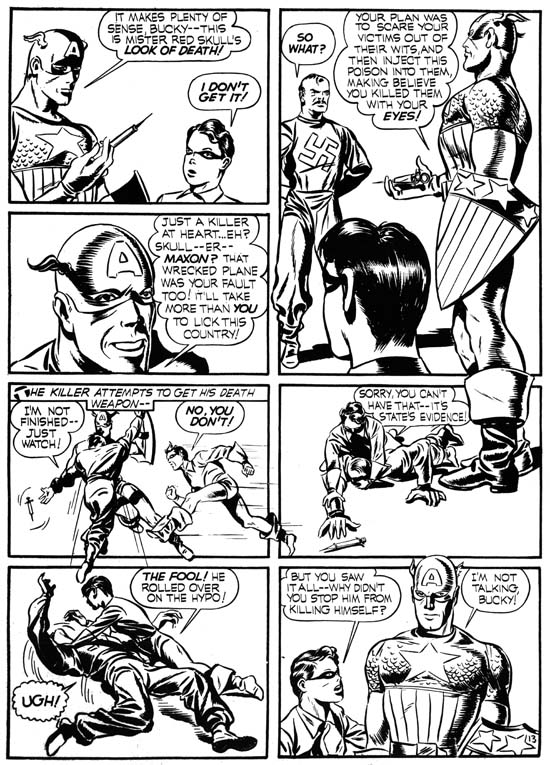

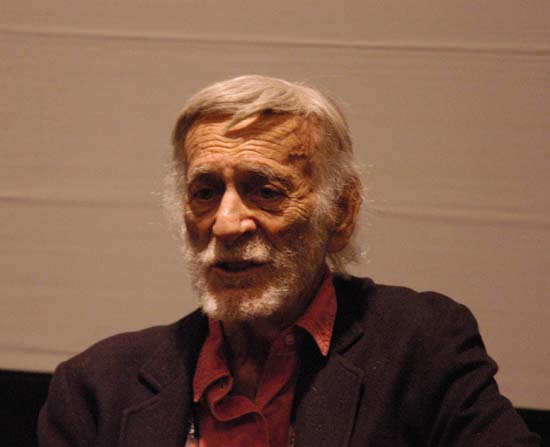

Joe was part of the amazing Legends Panel. What a roster; Murphy Anderson, Jerry Robinson, Stan Lee, Irwin Hansen, Ramona Fradon, the moderator and comic historian Michael Uslan, Dick Ayers, Joe Sinnott, Joe Simon and John Romita Sr. I took some pictures which I will include at the bottom of this post. Unfortunately it was mobbed and I was unable to get any of Ramona Fradon. With such a large panel there really were not a lot of questions that could be done in one hour. One question asked of each panelist was among the artists that they had worked with who were their own favorites. Of course with panelists such as these, Jack Kirby was brought up by a number of them. Jerry Robinson’s answer of Bill Finger got a good response from the audience, but what warmed my heart was his other choice, Mort Meskin. When the question got to John Romita he talked about how influential the first issue of Captain America was to him. After which Stan Lee took back the microphone and said how much that issue influenced him as well. Stan continued to say that he was there when Simon and Kirby were producing Captain America, he saw both Jack and Joe drawing Cap and he could not tell one’s art from the other. Further that Joe did not get the recognition that he deserved for all his contribution to the art and the writing.

On Saturday Joe spent an hour with Mark Evanier jointly signing Mark’s new book “Kirby the King of Comics”. I do not think I have mentioned that book previously on this list, largely because it had received such great publicity that I am sure most of my readers were already aware of it. It is an incredible book; the publisher Abrams did a great job reproducing the art and Mark’s biography nicely covers Jack’s long career. Of course all Kirby fans are really waiting for the more detailed biography that Mark has said should come out in a couple of years. Unfortunately he has been saying that for many years, we shall see. I only had about a minute at the end of the signing to tell him how great “Kirby the King of Comics” was and how much I enjoyed his other books like “Dr. Wertham Was Right”. Besides being the leading Kirby scholar, Mark is a wonderful writer. I was surprised that Mark recognized my name and that he had read my blog. He commented that he did not agree with everything I have said. My reply was something to the effect that it was to be expected. There was no time then to expand on that comment but I have written before in some of my posts that I do not expect everyone to concur with me. People will always disagree on methods and conclusions. But no matter how important the subject matter is to us, a different opinion is not a personal affront.

After the Abrams book signing arrangements were made to find a place in Artists Alley for Joe to do some more signings. Peter David agreed to make some room at his table for Joe. Peter David, how cool is that? Joe loves kids, so he gave Peter’s young daughter a signed copy of his letterhead (with all those characters that Joe has worked on over the years). Peter’s wife (sorry I forget her name) told her daughter that Joe was a real artist. I must admit chuckling over that comment. She explained that their daughter was aware that her father wrote comics but did not have occasion to see how the art came about. Since Joe’s appearance in Artists Alley had not been previously announced we were not crowded as badly as at the Abram’s booth. Joe still get a lot of attention anyway, it was just not as hectic and allowed more one on one.

Sunday included a Kirby panel moderated by Mark Evanier with Dick Ayers and Joe Sinnott. Attendance was a little low but it was very well received by those present. Great questions from Mark and great stories from the panelists. It was a moving experience just to be in a room with a bunch of Kirby fans. I wish it could be that start of a new tradition for the N.Y. Comic Con.

Also on Sunday was a showing of “The Legends Behind The Comic Books”, a documentary by Michael Uslan made in conjunction with an exhibition of comic art held last year at the Montclair Art Museum. The video opened up with various legendary artists saying that they never thought that comic book art would ever be considered important. They might not have thought so but that was not true of all comic artists. One artist (John Romita?) told a tale of a lunch at the Playboy Club in the ’60s where Jack Kirby predicted that comic book art would someday hang on the walls of museums. Nobody believed him.

On a personal note, I had my first opportunity to meet Jim Amash. Jim has done many great interviews over the years but his latest one of Joe Simon can be found in Alter Ego #76. Jim said that response generated by that interview was much greater then any of those he had done previously. I pointed out, as I have in this blog before, how well Jim managed to bring out the real Joe. Jim mused that perhaps that was because he and Joe were such good friends. Well I would not doubt that for a moment, but I think that Jim’s long time expertise on giving interviews had something to do with it as well.

Ernie Colon, Sid Jacobson and Joe Simon while Joe was waiting for the panel. The three had previously worked together at Harvey Comics. Ernie and Sid are still active and their “The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation” was recently released.

Jerry Robinson and Joe Simon having a discussion before going to the panel.

Jerry Robinson and Irwin Hansen on the way to the panel.

Mark Evanier greeting Joe Simon just before the panel started.

Joe Simon and Stan Lee also just before the panel started. I suspect that the panel was delayed by all the greetings between panelists. I did not care because I was having too much fun snapping pictures.

Joe Simon, Joe Sinnott and John Romita. Sinnott and Romita never worked with Simon but they exchanged warm greetings nonetheless.

Dick Ayers and Joe Simon. I believe Dick said that he never worked for Simon and Kirby but in a way he worked for each separately.

Joe Sinnott, Stan Lee and John Romita Sr. after the panel was over.

Jerry Robinson relaxing after the panel.

Murphy Anderson looking like a million bucks. Not the stereotypic image of someone from the comic book industry but still a great artist.