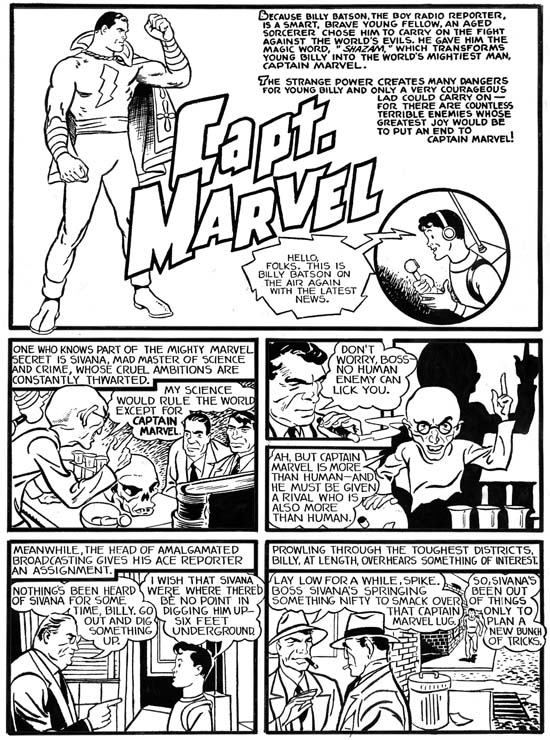

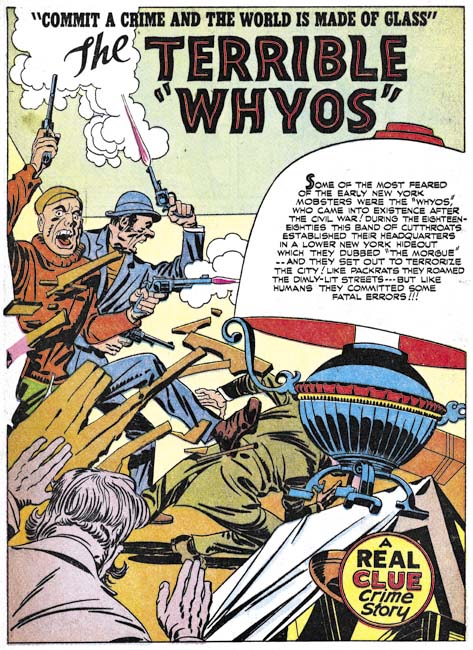

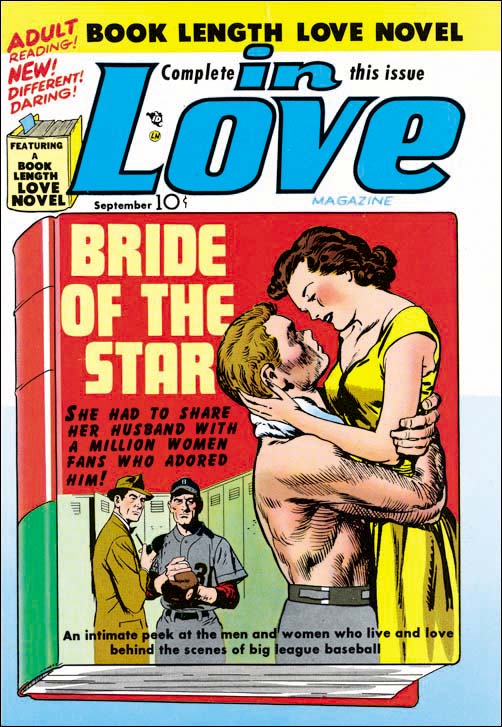

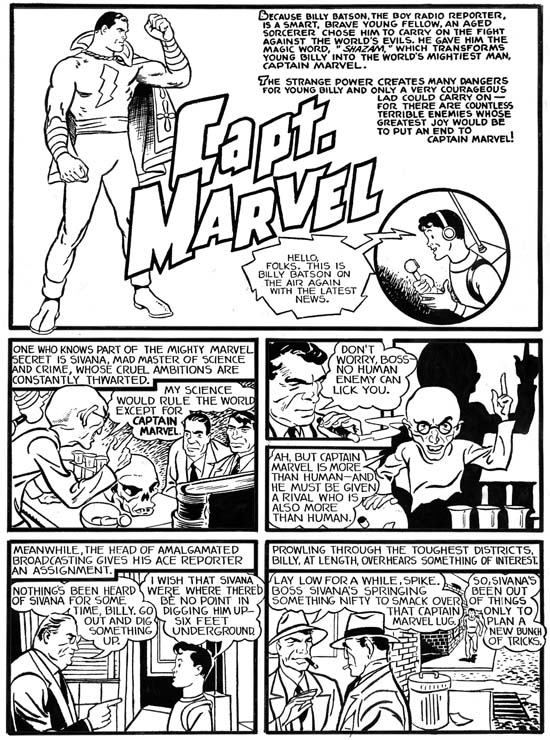

Captain Marvel, Special Edition (March 1941) bleached page art by Jack Kirby

Captain Marvel, Special Edition (March 1941) bleached page art by Jack Kirby

Not very long ago Ken Quattro (the comics detective) posted some court transcripts of testimony that was given during the DC versus Fox copyright infringement trial. This trial concerned DC’s claim that Fox’s Wonder Man was a copy of Superman. The transcripts of a number of witnesses was provided but the most surprising was that by Will Eisner. In the past Will Eisner had always maintained that, despite pressure from Fox to take the blame, he had told the court that Fox had instructed him to copy Superman. But the court transcript that Quattro obtained showed that in fact Eisner denied that Wonder Man was a copy of Superman. The transcript is a fascinating discovery that re-wrote comic book history as we know it.

The DC vs. Fox transcript brought to mind another trial, that of DC versus Fawcett. This was actually a more important case because Fawcett’s Captain Marvel was selling quite well, perhaps even better than Superman. One aspect of this lawsuit was of particular interests to me because in his book “The Comic Book Makers” Joe Simon had a chapter describing how he became a witness at the trial. I have recently had the opportunity to read a transcript of Joe’s appearance. Right up front, I want to say there were no big surprises to be found in the transcript. But in light of the historical importance of the DC/Fawcett trial I thought I would write about what the record shows.

Joe’s first appearance in court was on March 9, 1948. Under questioning from the plaintiff (DC) Joe first provided a brief description of his career. Mostly Joe dwelled on his work as a newspaper staff artist and while he mentioned the newspapers he worked for, Joe did not go into detail about the comic book publishers he had dealt with.

Then Simon was asked about his involvement with Fawcett Publications. Joe describe being contacted by Al Allard, Fawcett’s art editor. Simon was asked if he was willing to take on an assignment to put together a magazine of Captain Marvel. This work would end up being Captain Marvel Special Edition, the first time the big red cheese had appeared in his own comic book have previously appeared in Whiz Comics. Allard stated that Captain Marvel was a “take-off of Superman”.

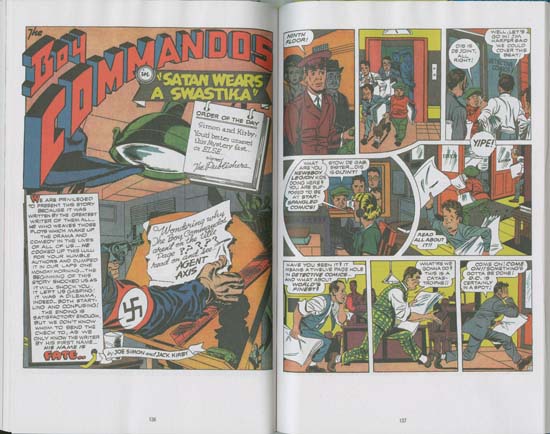

Joe returned later with some sketches of Captain Marvel that he and Jack Kirby had drawn to show what they were capable of. Allard then introduced Joe to William Parker to supply the script. Ed Herror was also there. Joe asked Parker if they could make any changes in the script, telling him that they “were in the habit of changing script to improve the cartoon, having been writers and editors in the field ourselves”. Parker instructed Joe that they definitely could not alter the script, “they are following a definite pattern there, definite formula, and they had taken the formula from Superman”.

Joe brought the pencils for each story one at a time back to Fawcett for lettering. Afterwards they were retrieved and inked. The final inked versions were delivered by both Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. The payment for this work was done by check sent through the mail.

The above testimony was in response to questioning by the DC lawyers, DC then requested that Fawcett supply the original art that Simon and Kirby had done which had previously been subpoenaed. Fawcett did not have the art at that time and therefore questioning of Joe was stopped for the day.

The date that Simon reappeared as a witness is difficult to read on the copy of the transcripts that I saw. I believe it was either March 13 or 15. The original art that Simon and Kirby created for the Captain Marvel comic was then available. Under questioning from the DC lawyer Joe discussed the changes that had been made to the original art, which seems to have been rather abundant. From his testimony the changes had been made in both the penciled and the inked art. A copy of the published comic book was available but instead Simon would identify the changes by the art style. The most memorable change was that a rifle that in the original Simon and Kirby version was bent “so that it could shot around corners” had been altered into being bent like a pretzel. The DC lawyer produced a large photostat from the summer 1940 issue of Superman which also had a rifle similarly bent.

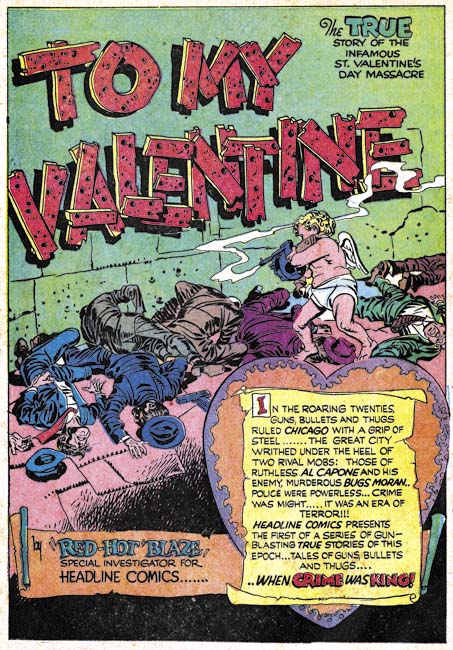

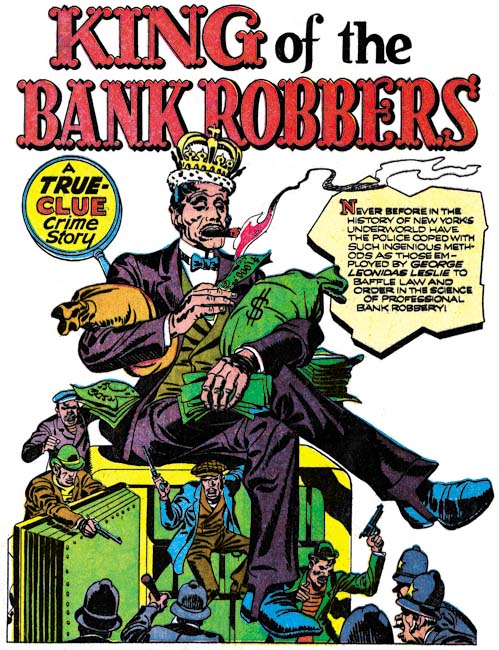

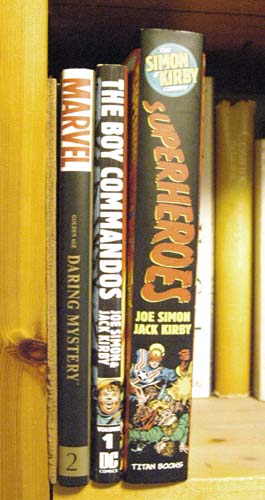

Joe was then cross examined by the Fawcett lawyer. First he was asked about his latest employment which was by Crestwood Publications (which in my blog I normally refer to as Prize Comics). On questioning, Simon reported that he got paid on a royalty basis. The lawyer asked to verify that if Crestwood was not satisfied with the art that Simon and Kirby produced then they do not accept it. Joe corrected that as part of their agreement they have to accept it whether they liked it or not. He added that they have never disliked anything they had done. On questioning about the characters that Simon and Kirby did for Crestwood Joe replied that the only “natural character” was Charlie Chan. He said that they had produced two issues to date but that none of they had yet to appear on the newsstands. As for other characters that Simon and Kirby produced “all others were true stories”. (At the time of this testimony Simon and Kirby were producing Headline, Justice Traps the Guilty and Young Romance.)

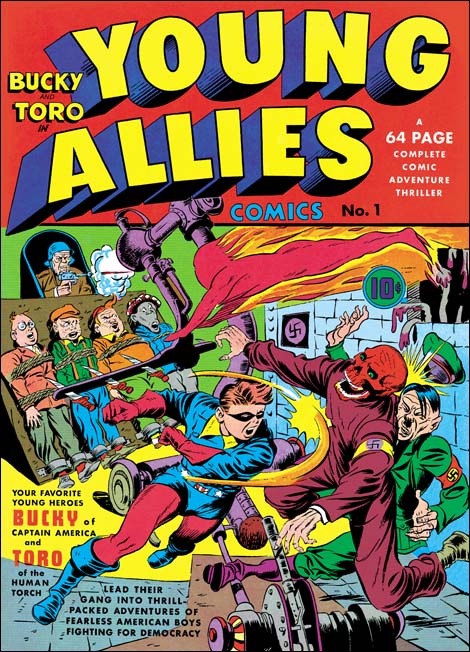

On questioning about other characters that Joe had previously created he mentioned Marvel Boy, Young Allies, T-Man, the Newsboy Legion and Captain America. The Fawcett lawyer seemed intent out getting Joe to describe the costume but the DC lawyer would object, sometimes successfully and other times not.

Joe was asked how long he had known Herron, Allard and Parker which in all cases was not long before working on the Captain Marvel comic. The Fawcett then proceed to question Joe about the changes to the art. The lawyer would ask Joe if there was any indication of whiteout on some panel. And Joe kept trying to explain that whiteout was not required for changes to the pencils and that he could tell what was changed by the style.

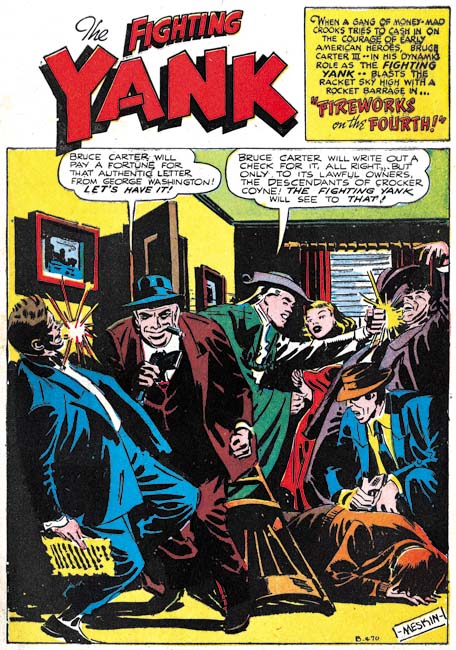

During redirect by the DC lawyer, Joe was asked about what other work he had done for Fawcett. Joe stated that while they did no more work on Captain Marvel they later did some for Wow Comics (this would by Mr. Scarlett that appeared in Wow #1).

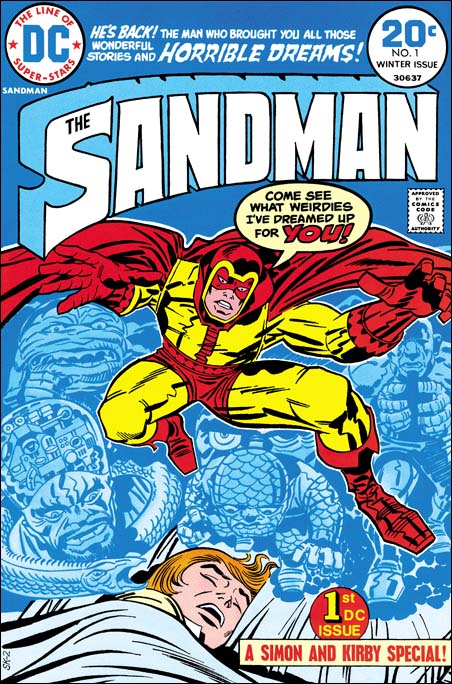

On recross by the Fawcett lawyer, Simon was questioned about whether he had heard Mr. Herron testify to writing scripts for Captain America and Joe had answered that he was not present at Herron’s appearance. Joe was asked if he had done the art for the Sandman character from Adventure Comics #87 which he had done for “several issues”. One objection from the DC lawyer, Fawcett said that they trying to show that “he draws not only characters having these traits but he draws them for the plaintiffs”. Joe was also questioned about Manhunter.

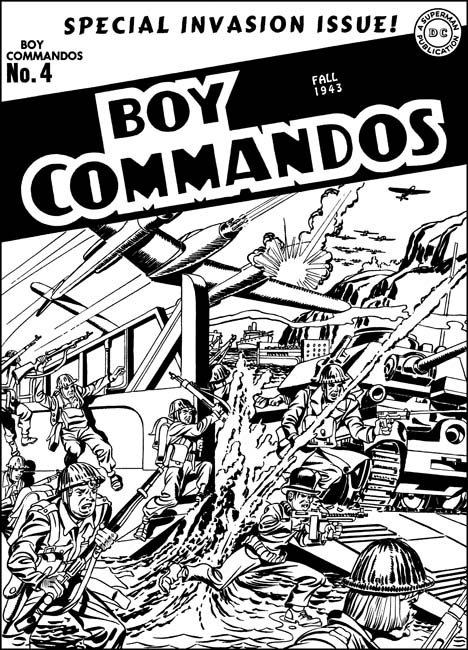

Like I wrote at the beginning, there are no big surprises in the testimony. Joe mentioned a few times that people at Fawcett had admitted to him that Captain Marvel was a copy of Superman. Simon was not asked this directly but since he was DC’s witness I presume they were already aware of what Joe would say. In “The Comic Book Makers” Joe says that before the trial the DC lawyer “skillfully led us into the testimony he was seeking”. Another objective of the plaintiff (DC) seemed to be the reworking of the art. It was not elaborated during Joe’s testimony but I believe it was DC’s argument that these changes were made to make the art more similar to that found in Superman. The defendant’s, Fawcett, objectives seem to be to discredit Simon as a witness. Their attempts at questioning Joe about the art changes seemed to be directed at making it appear that Simon could not reliably identify the changes. The questioning about Joe’s career and the work that he had done for DC was clearly aimed at “trying to test the credibility of the witness’s testimony”. The idea being that if Joe worked for DC his testimony was biased. Surprisingly Fawcett never just asked Joe directly if he was currently doing work for the plaintiff. Had Fawcett asked that question Joe would have had to answer yes since Simon and Kirby were still doing Boy Commandos.

Simon’s testimony does provide evidence about one detail of comic book history. Sometime back I read the suggestion that Simon and Kirby’s Mr. Scarlett was done sometime before their work on Captain Marvel Special Edition. This suggestion was based on a dates provided from a second source for the Captain Marvel Special Edition and Wow #1 (in which Mr. Scarlett first appeared). Unfortunately neither comic has a proper cover date. Joe’s testimony places the Captain Marvel work before that done on Mr. Scarlett.

Captain Marvel, Special Edition (March 1941) bleached page art by Jack Kirby

Captain Marvel, Special Edition (March 1941) bleached page art by Jack Kirby