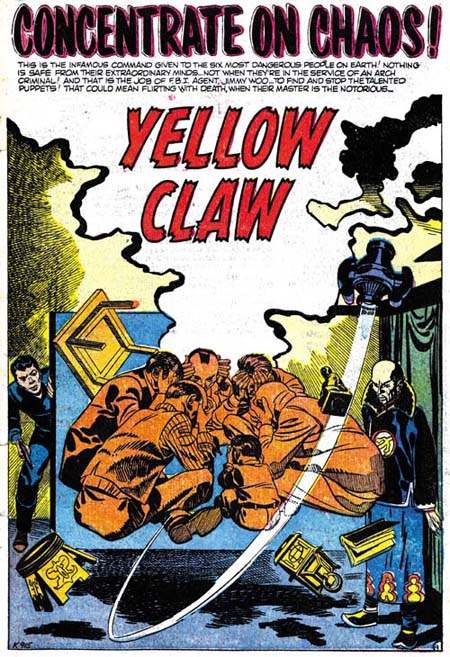

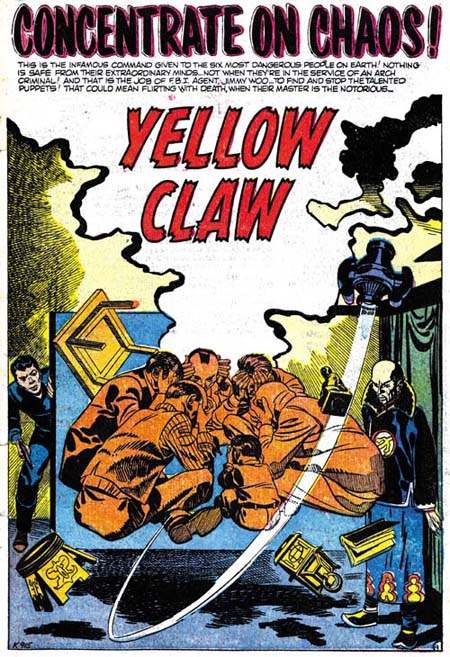

Yellow Claw #2 (December 1956) “Concentrate On Chaos” by Jack Kirby

Previously in the End of Simon and Kirby started their own publishing company in August 1954 which unfortunately would fail after April 1955. The pair received some income from having Charlton published remaining issues from the now defunct Mainline comics. They also produced work for Western Tales published by Al Harvey. 1956 would find Jack doing pretty much the entire contents for the Prize romance titles as well as supplying some covers for Harvey comics. It appears that Joe was doing some editorial work for Harvey. The all Kirby romances would end in December 1956.

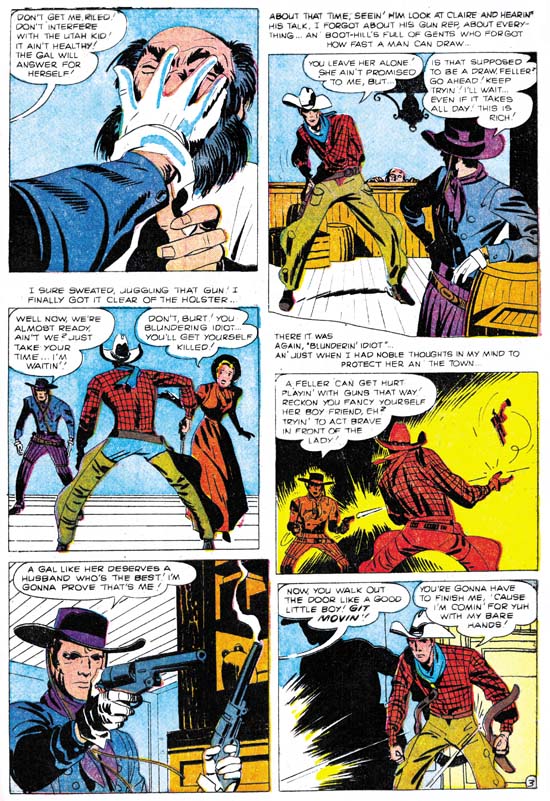

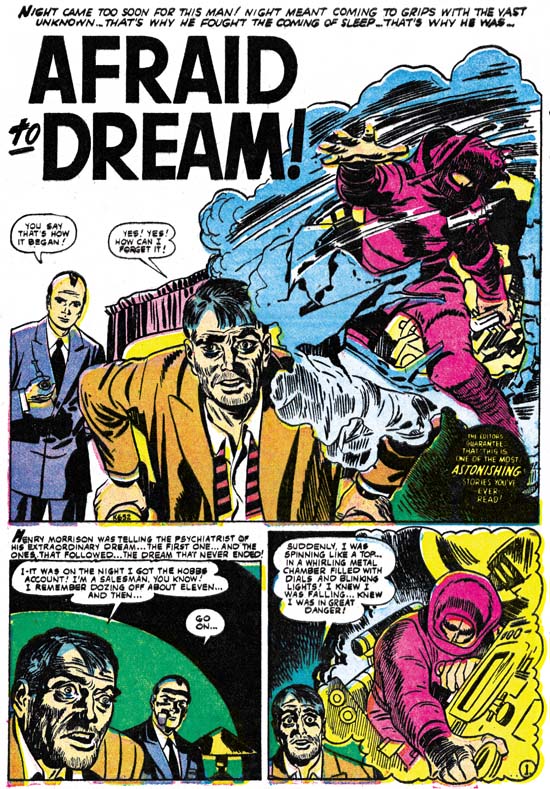

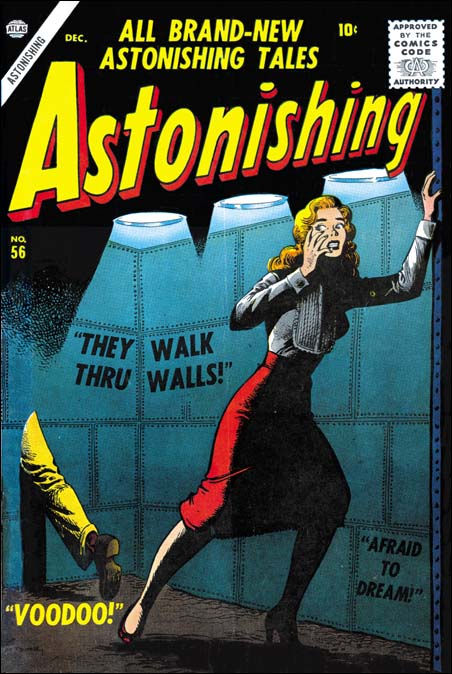

Things must have looked financially bleak for Jack towards the end of 1956. Mostly he was working on three bimonthly romance titles for Prize. If he was still receiving a share of the profits he may have realized that Prize was in trouble. Two of the romance titles would be cancelled after December. Kirby would turn to Atlas and DC for work as a freelance artist. The Jack Kirby Checklist has Battleground #14 (November 1956) as the first work for Atlas. In December Jack would do the entire contents for Yellow Claw #2 which he would also do for issues #3 (February) and #4 (April). Showcase #6 (February 1957) published by DC would introduce Challengers of the Unknown. This hero team would appear in four issues of Showcase before being launched in their own title. During the following months Jack would do other work for DC, mostly in their horror/science fiction titles. Actually Kirby would do work for both Atlas and DC at the same time, although as the year progressed Jack would work primarily for DC. This was probably due to the higher page rates at DC and problems Atlas was having.

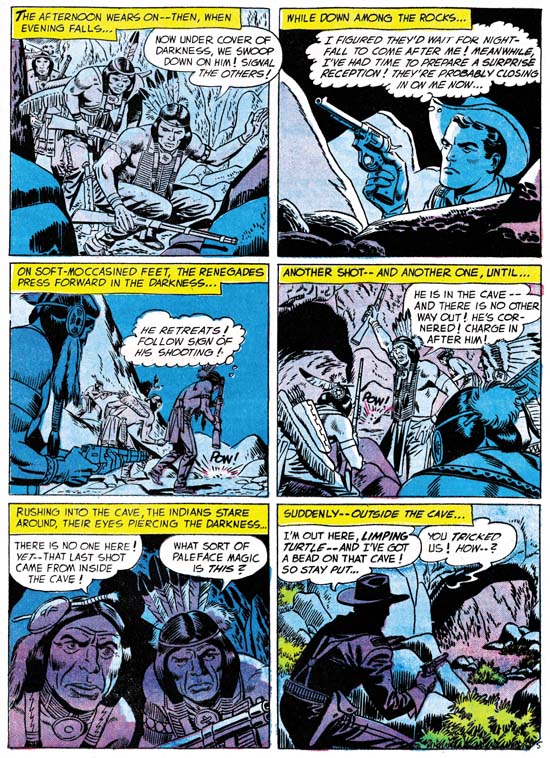

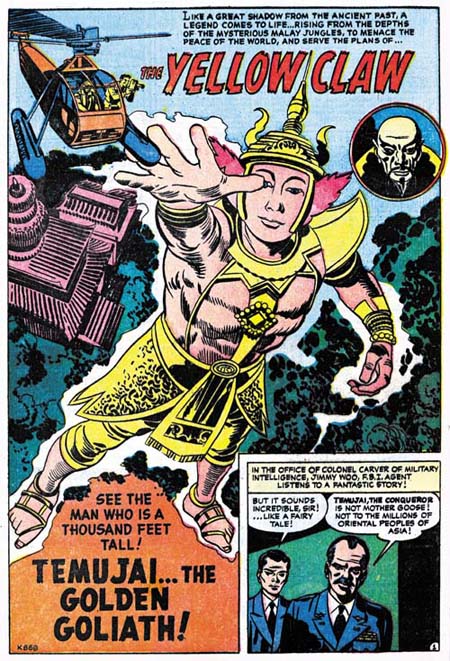

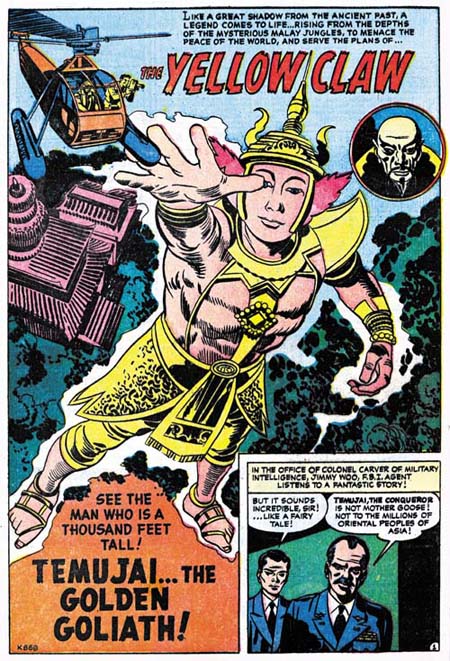

Yellow Claw #2 (December 1956) “Temujai, The Golden Goliath” by Jack Kirby

The Yellow Claw was the creation of Al Feldstein and was originally drawn by Joe Maneely. It was unusual in that the main protagonist was the villain, a Chinese mystic purportedly working for the Communists, but actually intending to rule the world himself. As a mystic the Yellow Claw has such powers as the ability to control mens’ minds, to observe from great distances and to fake a man’s death. In the first issue Maneely did a fine, if rather dry, job but the stories themselves are not all that exciting. All that would change when Jack Kirby took over in the second issue. This was years before the Marvel Method, but even so it is clear that the plotting of the stories is by Jack. We find a psychic committee that can alter reality, a giant robot masquerading as a oriental deity, a microscopic army, a space alien and more. Not only does Kirby pull out all stops for the plots, he produces some of his best pencils. But even more special is that fact that Jack would provide the inking in issues #2 and #3. What a fantastic inking job Jack did. Although he retains some of the features that he showed in the all Kirby romance comics from the previous year, some of the older shop style inking returns, now done with a finer brush.

These two Kirby issues are nothing short of masterpieces. The only flaws are comparatively dry covers by other artists and the Yellow Claw’s emblem that Jack inherited which looks too much like a chicken foot. Unfortunately for issue #4 all the inking was done by John Serevin who almost overpowers Jack’s pencils. How did these issues come about? It is hard to believe an artist so recently starting at Atlas, even Jack Kirby, would just be given free rein. More likely, having been offered to work on Yellow Claw, Jack quickly returned with a proposal that not only included art, but a script as well. Even though he was hired as a freelance artist, it is obvious that Jack wanted something more. If Yellow Claw did not work out, who knows some other proposal from Kirby might have? But alas it was not to be, a few months after the end of Yellow Claw, Atlas would not appear on the comic book racks for a short time in an event now referred to as the implosion. Atlas would start up again, but it would be a very different company with a much reduce line of comics. After that there was little chance that Jack could arrange a working relationship like he had in the Yellow Claw for Atlas again, at least not until many years in the future.

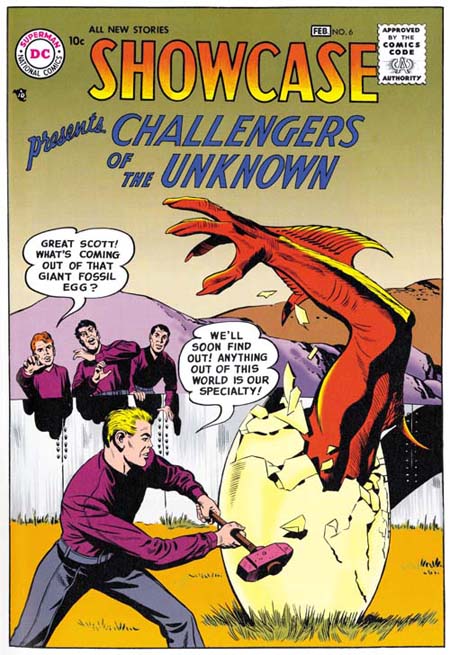

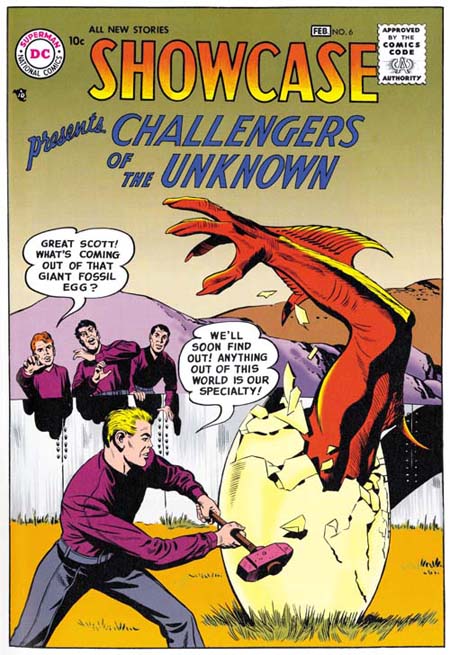

Showcase #6 January 1957) by Jack Kirby (from Challengers Of The Unknown Archives)

Like so much of comic history, the details of the birth of the Challengers of the Unknown are not clear. Joe Simon has said that he and Kirby jointly created the Challengers. I have read the original introduction to the Challengers reprint volume written by Mark Evanier were he states that Kirby told him the same thing. Incidentally that statement on the creation of the Challengers is almost certainly the reason that Mark’s introduction was rejected by DC and replaced when the volume was printed. In a legal deposition, Jack Schiff stated that the Challengers was pitched to DC by both Joe and Jack. If that is true, could some of the early Challengers stories actually be Simon and Kirby productions? Some have even suggested that they were originally meant for Mainline Comics, had their company survived long enough.

One of the unusual things about the first two issues of Challengers (Showcase #6 and #7) is the presence of oddly shaped panels, including circular ones. This is a layout device that Simon and Kirby had used often earlier in their career, but was not one found in their Mainline comics. I rather doubt that the Challengers stories were worked up early, therefore I suspect that it was done after the Mainline failure. Joe Simon has said that it was their practice that when then made a proposal, that they have a body of work ready to go. So it is likely the initial stories were drawn up while Simon and Kirby were still collaborating. But it was done during that time when each worked from their individual homes. That collaboration was very different from what it was previously. But none of the other S&K productions of that period have similar panel layouts. So although I fully believe that the Challengers was a Simon and Kirby creation, the drawing and panel layout of the initial issues owed more to Kirby and less to Simon.

The inking is odd mixture of spotting techniques similar to that in the all Kirby Prize romances of the last year, combined with some more naturalistic touches. For example on the cover to Showcase #6 (see above) on the fence toward the right edge we find an abstract shadow arch typical of S&K shop inking. On the fence to the left however we find shadows that were clearly meant to be cast by three team members. I would not call the spotting truly naturalistic, but there was a movement away from spotting that was completely abstract to one that tried to retain the design effect but still give a natural explanation. Although some of the spotting looks to me like Kirby’s hand, there appear to be other inkers also involved. Marvin Stein and Roz Kirby have been suggested by some. In any case although the inking looks nice overall, it simply does not match up to the effort done in Yellow Claw or even earlier Simon and Kirby productions.

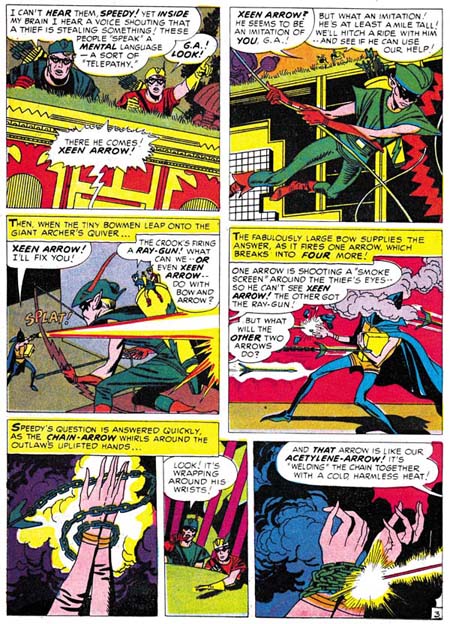

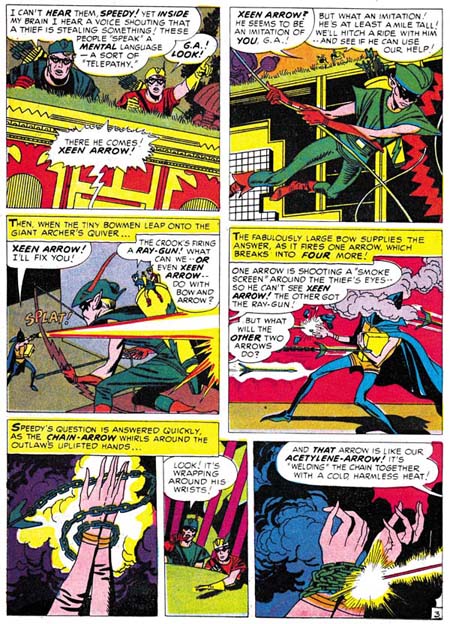

Adventure Comics #253 (October 1958) “Prisoners Of Dimension Zero” by Jack Kirby

Kirby would also take over the minor hero Green Arrow. Apparently Jack had some influence of the plots for Green Arrow because they would adopt a science fiction approach that seems pure Kirby. Here Jack also does the inking with, according to Mark Evanier, the help of his wife Roz. But the inking is rushed and way below the quality in the initial issues of the Challengers.

Generally as a freelance artist for DC and Atlas, Jack would be working from a script and would have no control over who would ink any pencils he submitted. Other then the examples I wrote above on, I really cannot say how much influence he had over the stories he drew. But I can say that Joe Simon played no part in any of this freelance work that Jack did. This is true even in the case of the Challengers of the Unknown. I do believe that Joe Simon joined Jack in pitching the Challengers to DC. I am sure that the two artists wanted an arrangement like the one with DC during the war. But DC now probably wanted full control and had little interests in sharing the profits. That left only the penciling, which would not pay much if shared by two. It is not the sort of arrangement that would interest Joe, so he left it to Jack alone.

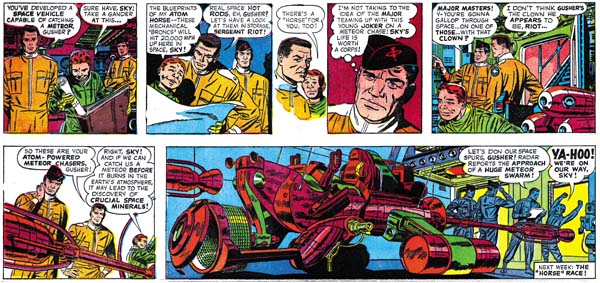

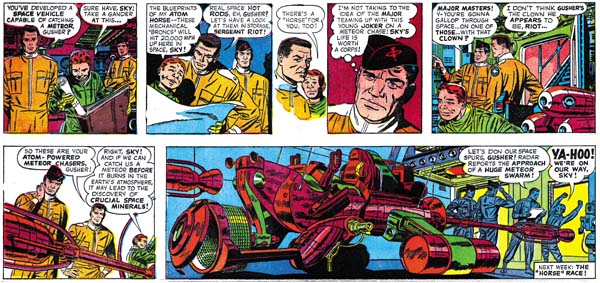

Sky Masters (2/15/59) by Jack Kirby

Life as a freelance artist was probably not ideal for Jack. But there were not many options open to him. Starting in 1957 he continued to provide some romance stories and covers for Prize (to be discussed in more detail in a future chapter), but there now was less of that work. Simon would continue to pitch new ideas to Harvey Comics (again to be discussed in a later chapter) but unless one of these projects became a blockbuster of a hit, Jack would really have to depend on his freelance work. On October 4, 1957 Russia surprised the world by launching the first satellite, Sputnik I. This spawned the space race and despite the fact that the Russians were ahead, America seemed confident that we could catch up. With the new interest in space came an idea for a newspaper syndication comic strip that ultimately became Sky Masters for Jack Kirby to pencil. The strip started in September 1958. The history of Sky Master is fascinating, but outside of our subject matter. But important to this discussion is the fact that legal actions about the Sky Master deal developed between Kirby and Jack Schiff, who unfortunately happened to be Kirby’s editor at DC. It was bad enough that Kirby lost the case in court, what was worse was the fact that he would no longer do any more freelance work for DC. The last DC work (Challengers of the Unknown #8) would be dated June 1959. The Sky Masters strip itself would end in February 1961. Unable or unwilling to get work from DC and therefore with even less options open to him, Kirby would depend more on Atlas for freelance work.

Chapter 6, A Friend’s Romance

Chapter 8, If At First You Don’t Succeed