I have a busy schedule with little spare time for wandering around the Internet. However there are a handful of blogs that I try to keep up with and one of them is Comics Should Be Good on the Comic Book Resources. They came to my attention when I was asked to do a guest blog there a little over four years ago (Simon and Kirby Meet the Shield). I am surprised they had found me out since at the time my Simon and Kirby Blog had a miniscule following. I have been following their blog ever since and I am particularly a fan of Comic Book Legends Revealed. I try to stop by once a week but sometimes my schedule just does not allow even that infrequent of a visit. That is what happened to me some weeks (before my undesired sabbatical) and so I was caught completely unaware of a recent entry for Comic Book Legends Revealed. One legend that Brian Cronin discussed was “Jack Kirby was the first comic book artist to draw splash pages” which he answered quite correctly as false.

I will discuss the subject of Simon and Kirby splashes further below but Brian’s post brought to mind the whole question of Simon and Kirby firsts. Not necessarily that Simon and Kirby did these firsts before other comic book artists but I will try to discuss that aspect as well. I should also admit that what I present here is a first attempt and by no means a definitive list. There is so much Simon and Kirby material that it would be easy to miss some earlier example. So I look at this as a work in progress subject to correction. Perhaps some of my readers can correct my mistakes.

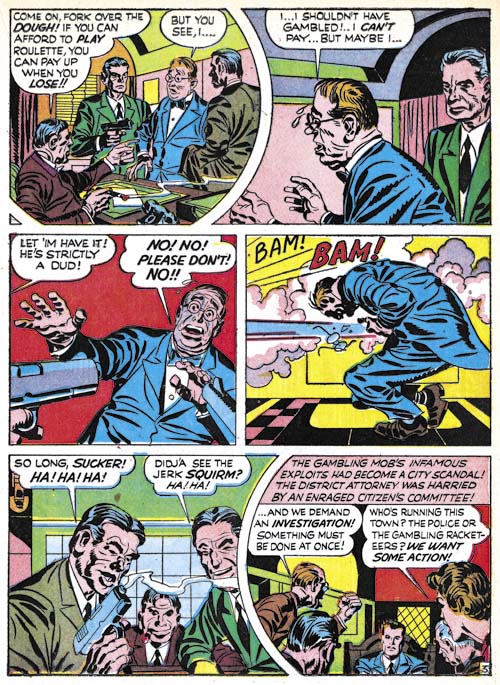

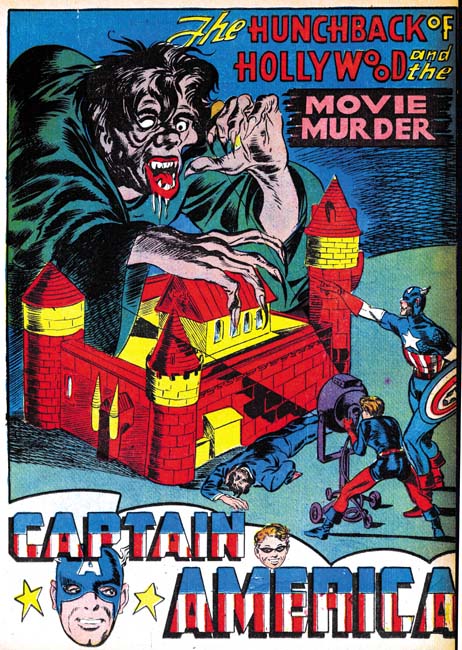

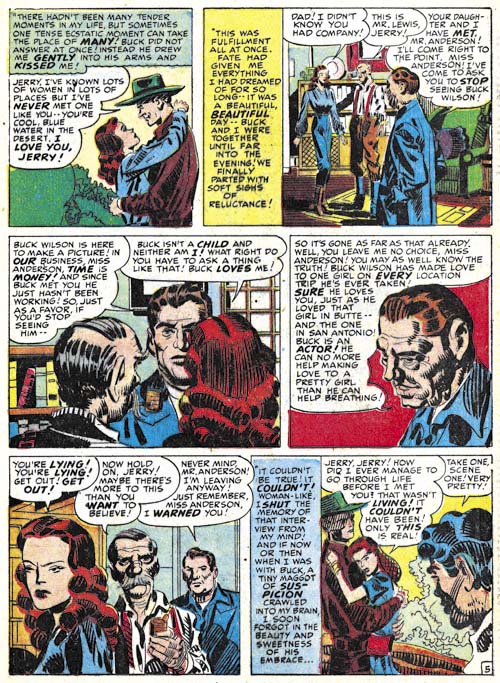

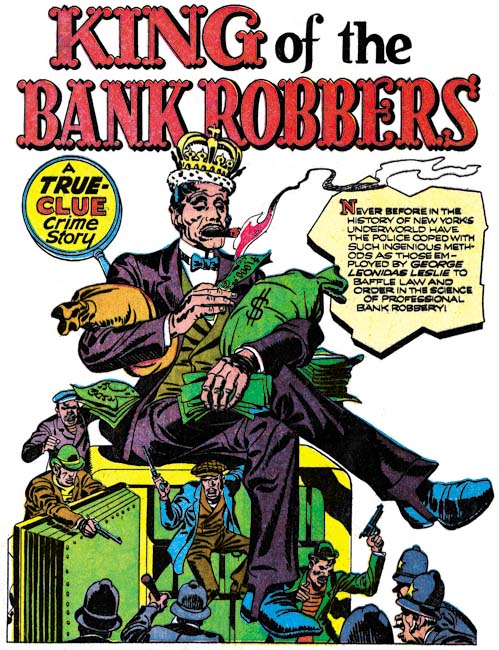

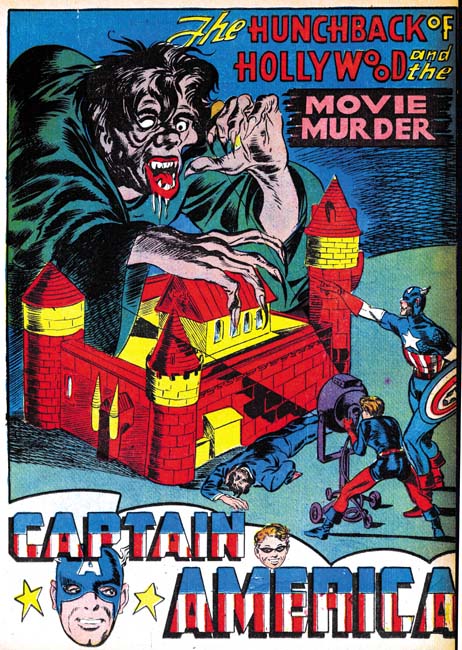

Captain America #3 (May 1941) “The Hunchback of Hollywood and the Movie Murder”, pencils by Joe Simon

So back to the question of Kirby or Simon and Kirby splash pages. Now I believe we have to be careful with our definitions. Besides references to liquids, a dictionary will define a splash as displaying conspicuously. Therefore one can say that any oversized panel in a comic book could be a splash. This is however a somewhat trivial definition and this type of splash appear well before either Kirby or Simon began doing comics. But Cronin’s question was about “splash pages” and by this I believe he means a full page splash without any story panels. Simon and Kirby have a long history of spectacular full page splashes. I believe the first full page splash by Simon and Kirby was “The Hunchback of Hollywood and the Movie Murder” from Captain America #3 (May 1941). But as Cronin points out full page splashes appeared in Detective Comics #39 (May 1940) so unless someone can come with an earlier example Bob Kane and Jerry Robinson should get the credit for that first.

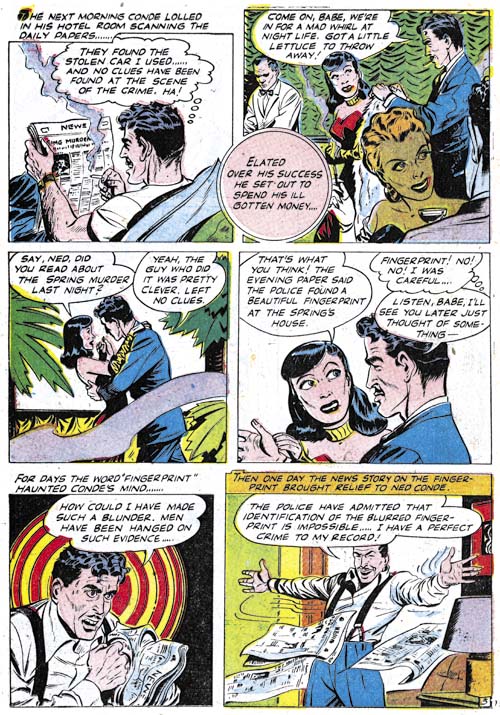

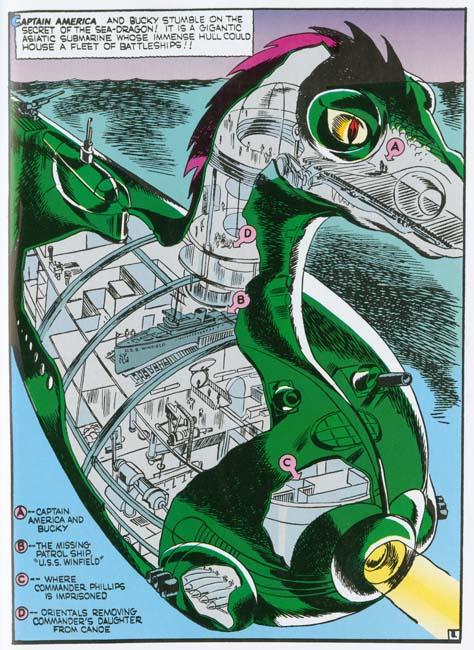

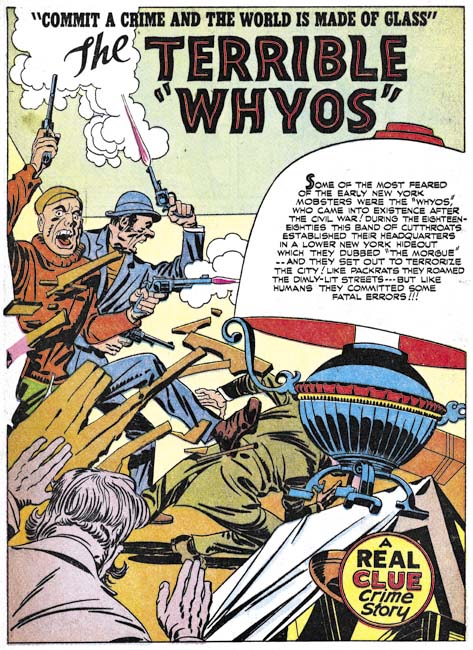

Captain America #5 (August 1941) “The Gruesome Secret Of The Dragon Of Death” page 8, pencils by Jack Kirby (from “Captain America, the Classic Years”)

Jack Kirby was famous for his interior splashes, that is a splashes that not just an introduction but are part of the story itself. The earliest example I am aware of is found in “The Gruesome Secret Of The Dragon Of Death” from Captain America #5 (August 1941).

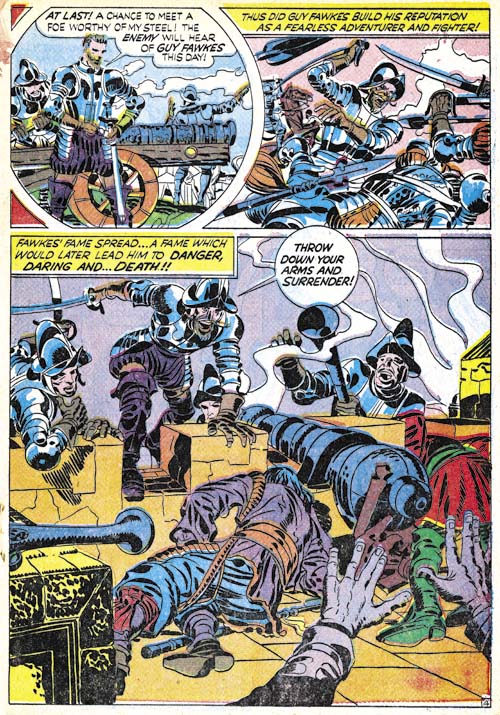

Adventure #75 (June 1942) “The Villain From Valhalla” page 8, pencils by Jack Kirby

However I suspect some readers will find the Captain America example unconvincing as this splash seems more like a diagram than part of the actual story. In that case the next example would by “The Villain From Valhalla” from Adventure Comics #75 (June 1942). And what a fantastic example it is, one of my favorite splashes. But is this truly the first interior splash page? I can by no means claim to have made a thorough search but I have never seen one earlier. In fact I cannot remember any other golden age artist doing it. So this might, just might, be a first for Simon and Kirby.

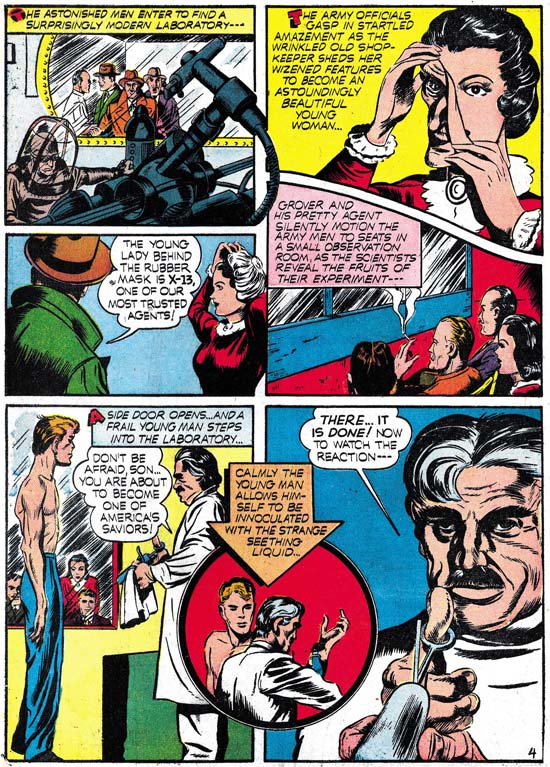

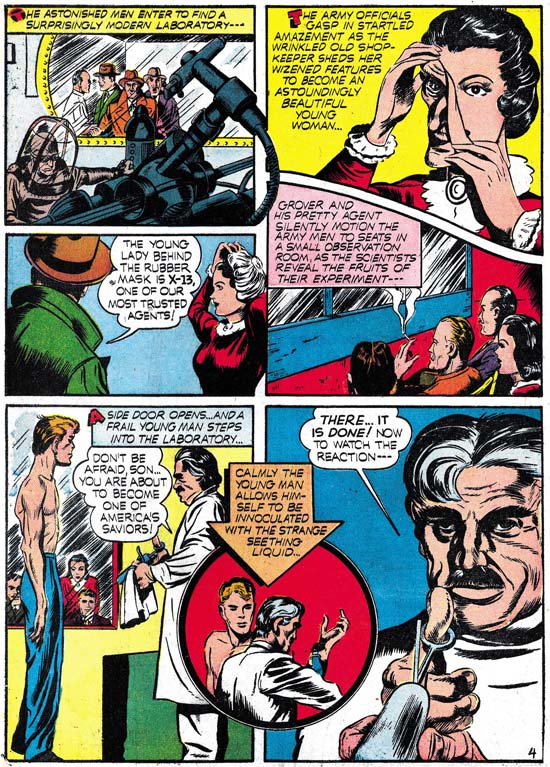

Captain America #1 (March 1941) “Meet Captain America” page 4, pencils by Jack Kirby

One of the things Simon and Kirby were famous for, at least early in the collaboration was the use of unusually shaped panels. I fear looking for the earliest Simon and Kirby use of irregularly shaped panels might end up in endless hair splitting. How far off from a rectangular does a panel have to be before it can be declared irregular in shape. So instead I went searching for Joe and Jack’s earliest use of a circular panel. Simon and Kirby’s first use of a circular panel was on page 4 of “Meet Captain America” from Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941). Circular panels played an important roll in Simon and Kirby productions until about 1947 when they were phased out (along with irregular panels as well). But were Simon and Kirby the first to introduce circular panels? Nope. It has been pointed out to me that circular panels appeared in earlier Batman stories. I cannot say when they started to use circular panels but Bob Kane and Jerry Robinson may have been responsible for that first as well.

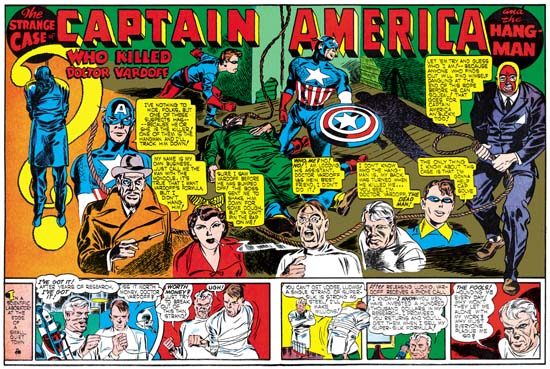

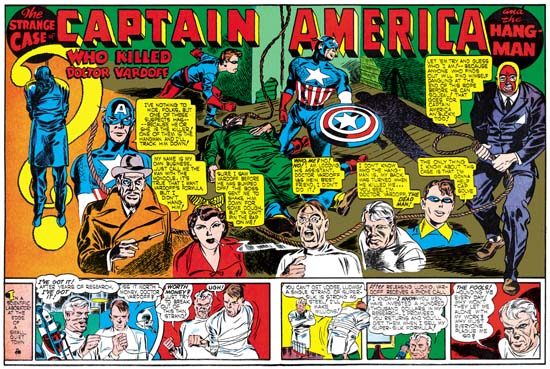

Captain America #6 (September 1941) “Who Killed Doctor Vardoff”, pencils by Jack Kirby

Larger Image

Simon and Kirby have often been cited as the first to do double page splashes. Their first wide splash appeared in “Who Killed Doctor Vardoff” from Captain America #6 (September 1941) (see The Wide Angle Scream). However I am pretty certain that Simon and Kirby were not the first comic book artists to do a double page splash. I clearly remember seeing a Kazar story from an earlier Marvel Mystery Comics although I do not remember the artist or what issue it appeared in.

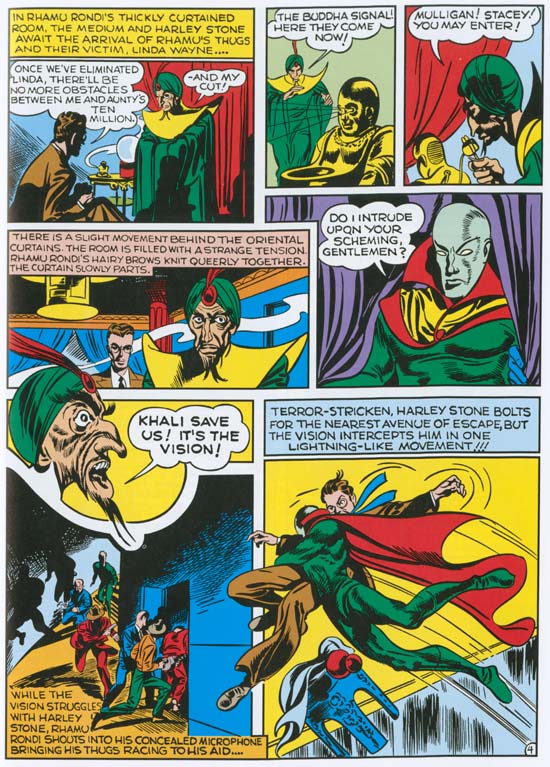

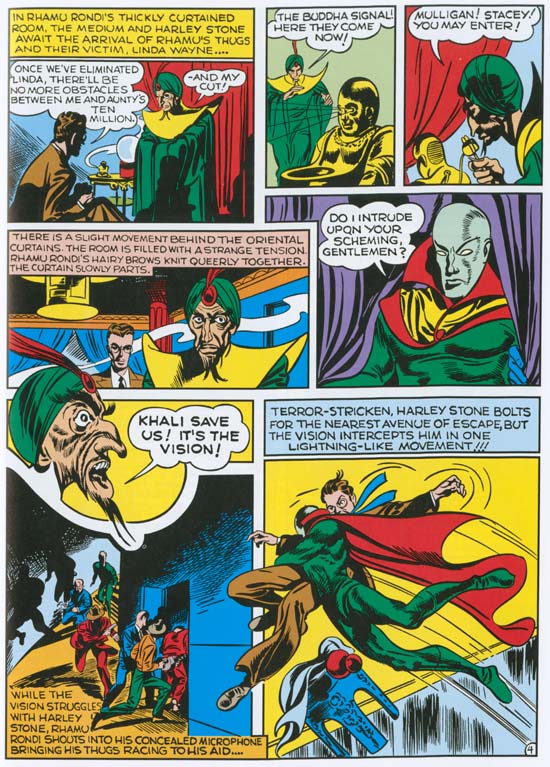

Marvel Mystery #15 (January 1941) “The Vision” page 4, pencils by Jack Kirby (from “Golden Age Marvel Comics” volume 4)

Another early technique that Simon and Kirby became famous for was extending figures outside a panel’s border. Done properly (and Simon and Kirby always seemed to do it well) this device could make a page visually exciting. Simon and Kirby used this technique during roughly the same period that they used irregularly shaped panels. The great success of Captain America influenced numerous comic book artists, but like the circular panel, cross panel border figures were probably not done first by Simon and Kirby. I cannot say for sure but I remember seeing earlier comic book art by Lou Fine which prominently showed this technique. Both Joe Simon and Jack Kirby were fans of Fine’s work and its seems probable that they picked up this technique from him. However I have no idea if Fine was the first to do this.

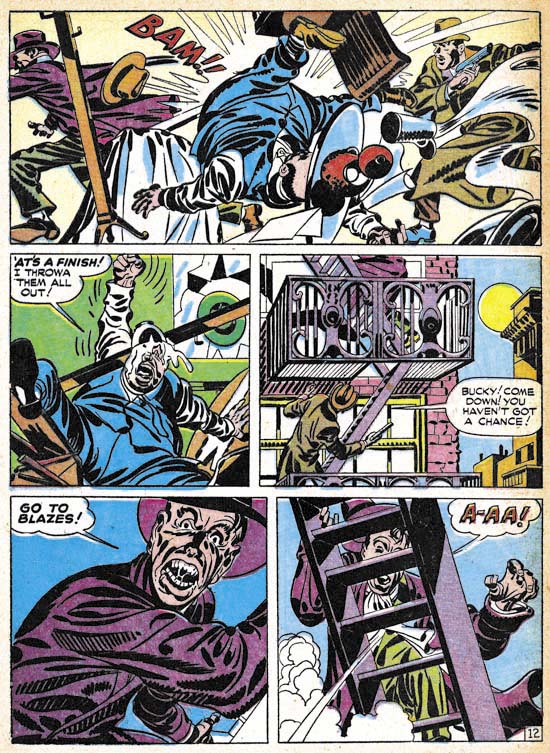

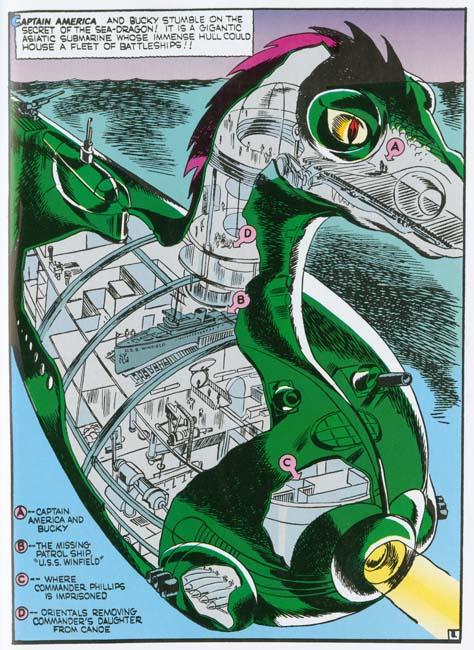

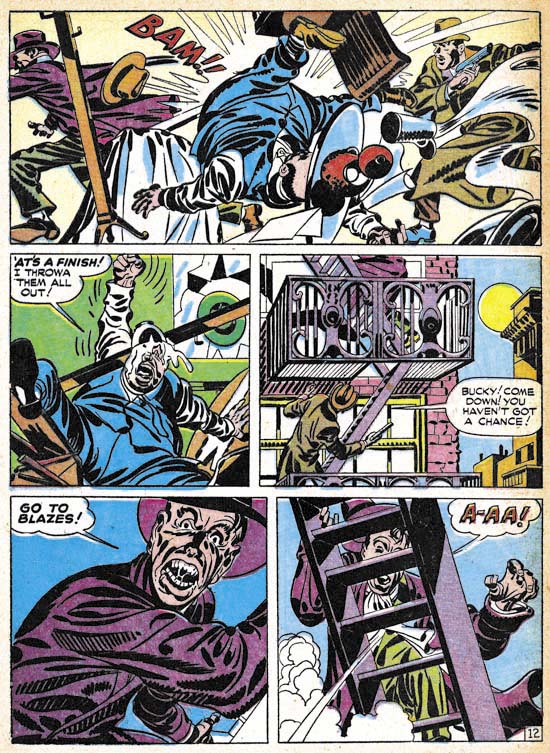

Real Clue Crime Stories, vol. 2 num. 6 (August 1947) “Get Me the Golden Gun” page 12, pencils and inks by Jack Kirby

Simon and Kirby generally inked their work in a blunt manner. After the war they developed a very distinctive style of inking which I call the Studio style. It was characterized by drop strings, abstract arches and most particularly by picket fence crosshatching (Inking Glossary). The picket fence crosshatching seemed to have a sudden appearance in their work. It appears in a fully developed manner and I have yet to find anything like it in early Simon and Kirby productions.

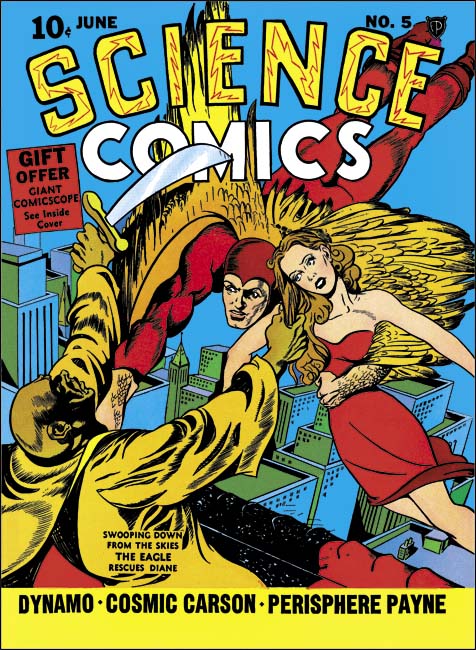

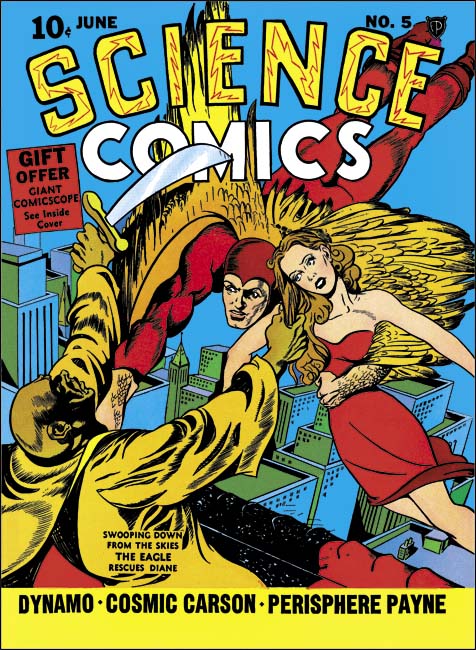

Science Comics #5 (June 1940), pencils and inks by Joe Simon

While picket fence crosshatching may have been unused by Simon and Kirby until they started doing crime comics, Simon used it much earlier before he teamed up with Kirby. The technique can be found in one of the covers Joe did for Fox Comics during his short stay as editor for that company. (It is a little hard to see in the scan above, but the picket fence inking shows up on the right sleeve of the yellow robed individual.) The example shown above may not done in a more refined and smaller manner but it looks very much what would be done years latter. Simon was purposely trying to imitate Lou Fine who had previously done the covers so I would not be surprised if Joe had picked that technique up from Fine as well. I know Will Eisner used picket fence crosshatching but I do not know if he had started using it at this point.

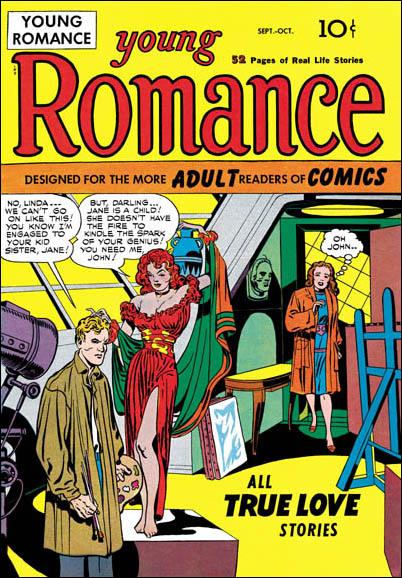

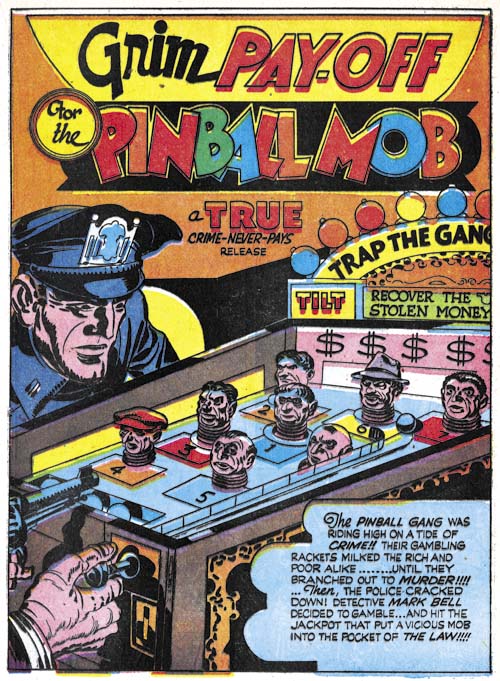

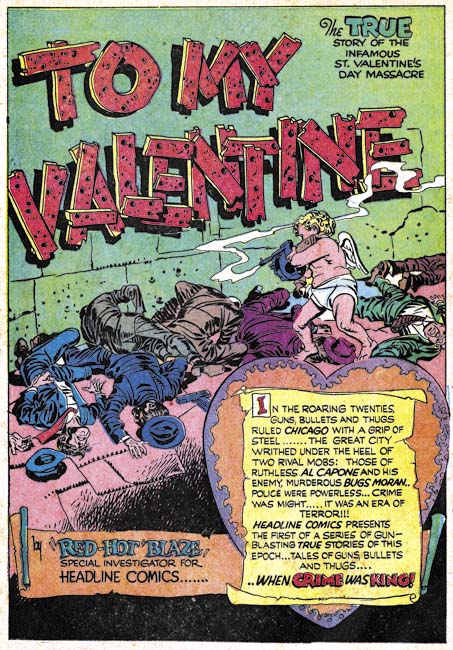

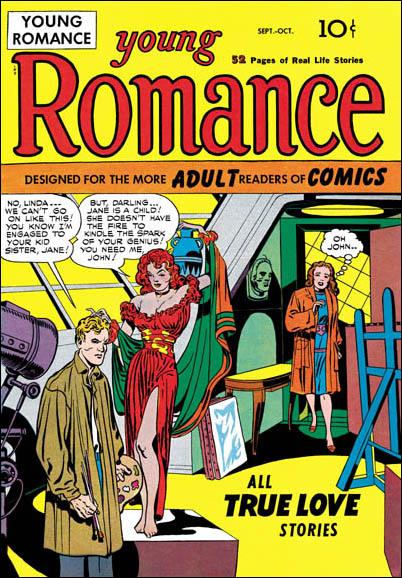

Young Romance #1 (September 1947) pencils by Jack Kirby

There is one first that I do believe truly belongs to Simon and Kirby and that is they were the first to create a love comic, Young Romance. Some have been very adamant in denying this but their case is without merit. Some cite My Date as the first romance comic (which would still give credit to Simon and Kirby) but My Date is a Archie swipe, not a romance comic. Others say Romantic Picture Novelettes was the first romance comic. But that comic was a reprint of the syndication strip Mary Worth was a soap opera and not a romance. And yes there is an important and distinct difference between the two. If that was not bad enough it is not at all clear that Romantic Picture Novelettes was published in 1946 as so often claimed. The comic itself bears no date and no one has supplied any evidence to backup the early date. For a more thorough discussion of this issue see my early post The First Romance Comic.

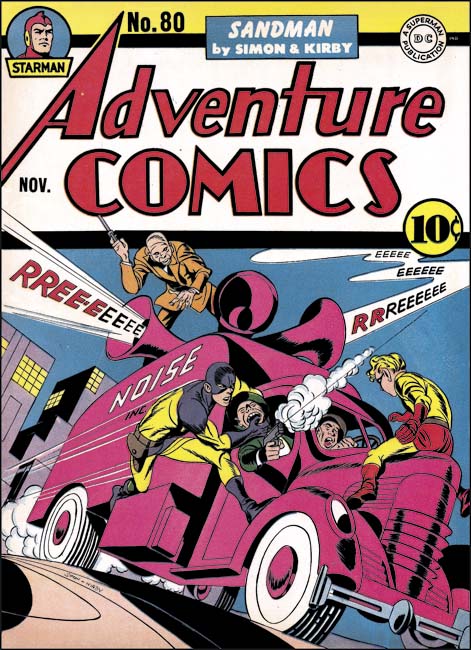

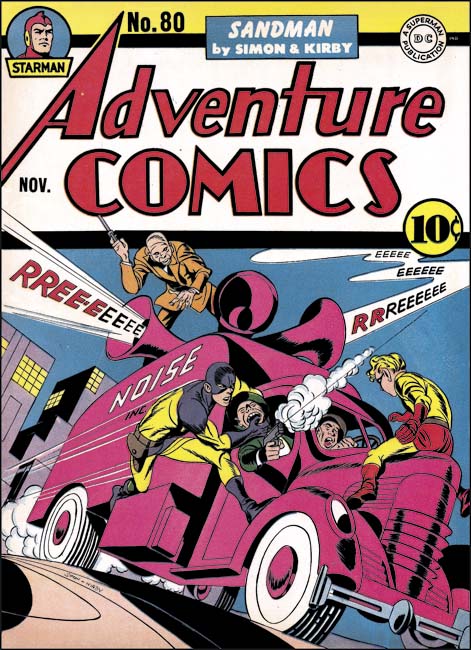

Adventure #80 (November 1942) pencils by Jack Kirby

Simon and Kirby’s great influence on comic book artists was not based on being the first to use some techniques but rather in doing so many things so well. Simply what makes Simon and Kirby important was they were the first to create really good comics. Now that is a first that is totally subjective and one I am sure some will disagree with and so it would be desirable to use a more concrete accomplishment. And there is one, Simon and Kirby were the first comic book artists whose names were used to sell comics. That is the first artist names to appear on the cover of a comic book. That was a big deal because initially it was characters that sold comics not creators. While other artists may have had their fans, it was Simon and Kirby who first became a brand name for quality.