Golden Lad #1 (July 1945) “The Heart of Gold”, art by Mort Meskin

Last week I provided some examples of early work by Mort Meskin. Now I would like to do the same for the period from after the war until Mort began working for Simon and Kirby. Actually I am being a little inaccurate by describing this period as post war. The war ended in Europe on May 8, 1945 and in Japan on August 15. The first issue of Golden Lad was cover dated July 1945. Because cover dates were usually advanced a couple of months from the actually released date, this issue probably hit the stands in May. Therefore the war was still ongoing when the art was created (which probably started in February). During most of the war Mort Meskin was doing work solely for National Comics. Mort would continue to provide work to DC while doing Golden Lad for Spark Publications.

Maybe it is just a question of luck as to which issues are available to me, but it seems to me that there was a decline over time in the quality of Meskin’s art for DC. However that decline only affected his DC work. While the Golden Lad character may not have been that great of a creation, the art Mort provided was first rate. The splash is particularly nice. Golden Lad rises dramatically from a cauldron of molten gold. The fire provides the only light for the scene giving the surrounded conquistadors with expressive shadows. But with their modern weaponry, they are not truly conquistadors. The heart of gold that provides Golden Lad with his powers was created during the time of the destruction of the Aztecs but Golden Lad fights modern criminals. The splash is a graphic amalgamation of the two concepts.

Golden Lad #2 (November 1945) “The Haven for All” page 5, art by Mort Meskin

I really cannot get very enthusiastic about Golden Lad himself. Like Superman, he is just too powerful to provide interesting stories. However Meskin did a good job on graphically depicting the story. The first panel shows the use of multiple images that Mort devised in Johnny Quick for indicating super fast action. The showing the unrolling of the sail might have seem the most obvious choice for panel 5 but Meskin’s depiction of the crowd’s reaction was probably more effective.

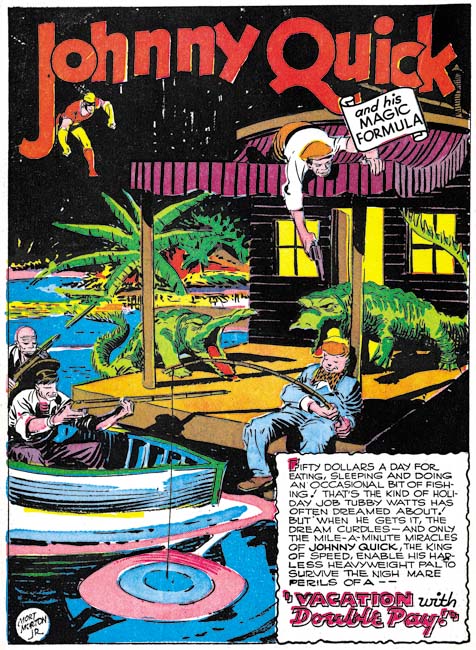

More Fun Comics #107 (January 1946) “Vacation with Double Pay”, art by Mort Meskin

As I said before, Mort’s art for the later DC work is not as impressive as his earlier stuff. This Johnny Quick splash is probably the best of the few I have available from his later DC work. Even here I do not find the approaching alligators truly threatening. What are they going to do, gum the fisherman to death? Some of this decline in quality maybe due to the inkers being used but perhaps Meskin was loosing interest after so many years. That he did such great art for Golden Lad shows that he had not lost his talent.

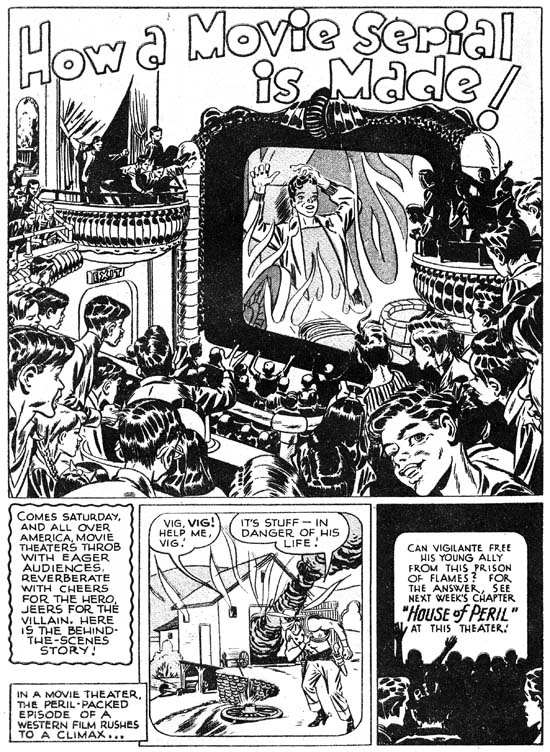

Real Fact Comics #10 (October 1947) “How a Movie Serial Is Made”, art by Mort Meskin

Meskin could do great work for DC as well, if it supplied enough of a new challenge. This scan of “How a Movie Serial Is Made” was provided by Ger Apeldoorn (Those Fabuleous Fifties). It certainly is an oddball feature. Meskin provides examples of how serial movies were created using his own character, the Vigilante. I particularly like the splash. While I am not old enough for movie serials, I do remember weekend matinees where there was a very similar response from the exclusively young audience.

Mort did other work during this period besides what he did for DC and Spark. This was the time that he did a couple pieces for Prize Comics (but this was not for Simon and Kirby). I will not be discussing the Prize stories here as I covered them recently in other posts (Treasure #10 and Treasure #12).

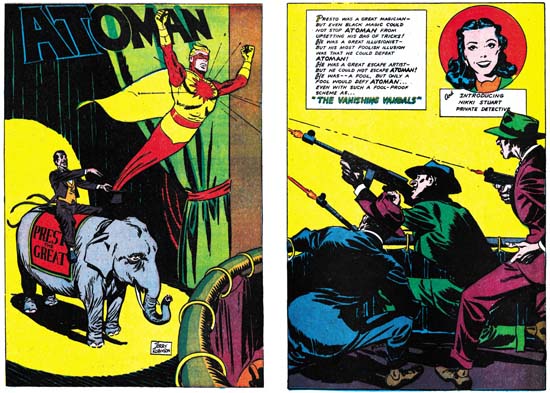

Atoman #2 (April 1946) “The Vanishing Vandals”, art by Jerry Robinson

Larger Image

Mort Meskin would later team up with Jerry Robinson. It would therefore be informative to provide examples of Jerry’s work. Much of what Robinson did previously was on Batman working for Bob Kane. This makes it difficult to come to a clear understanding as to what Robinson’s personal style really was. The one example I can supply was for Atoman, a title from Spark Publications, the same publisher that did Golden Lad. Here Jerry does an ingenious double page splash. The best location for a double page splash was the centerfold. Place one anywhere else and the two pages would have to be printed on separate sheets of paper. With the primitive printing of comics of those days there was little likelihood that the registration would work out properly in the finished comic book. Robinson’s wide splash is at the front of the comic but he avoids the registration problem by purposely including a gutter in the design that would separate the two image halves. He has not simply bisected the image; if you were to bring the two pages together they would not line up properly.

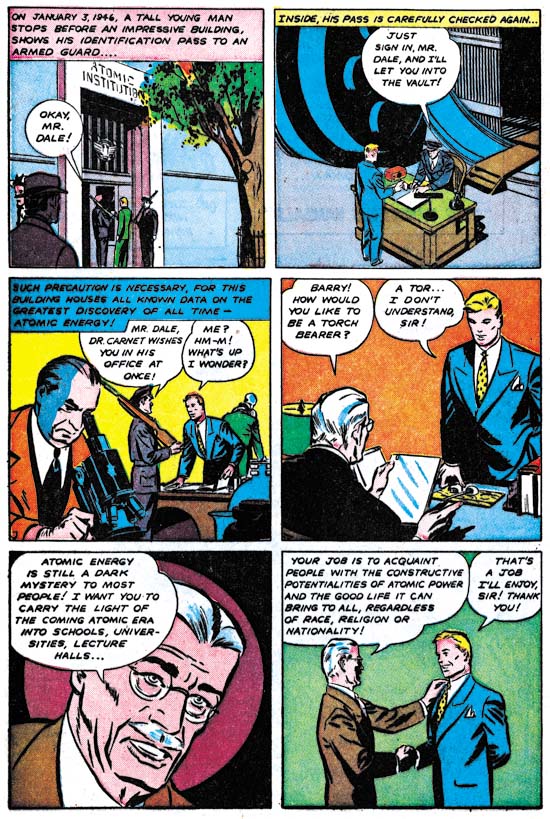

Atoman #2 (April 1946) “The Vanishing Vandals” page 3, art by Jerry Robinson

Here is an example of a story page from Atoman. But note the man in panel 5. He has to my eyes a distinctively Meskin look to him. There are a few other similar Meskin-like portrayals in the story as well. Was Mort giving Jerry a hand? Or was Robinson being influenced by Meskin and adopting some of his style? I do not have an answer but it is something to keep in mind when we examine joint efforts by Robinson and Meskin.

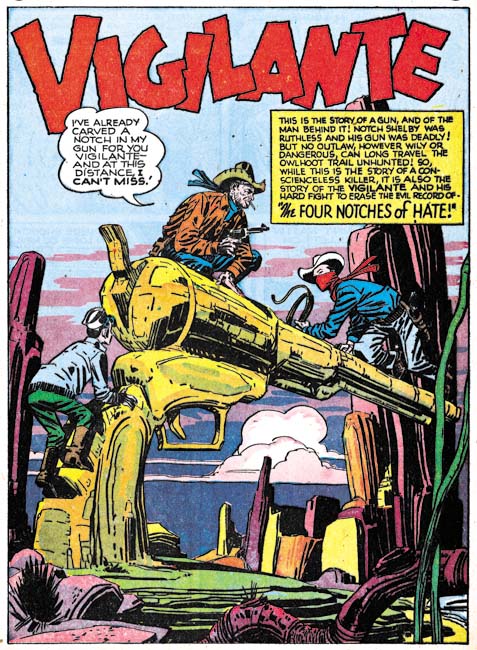

Western Comics #4 (July 1948) “The Four Notches of Hate”, art by Mort Meskin

In 1948 Meskin work for DC would be ending. Did Mort’s emotional problems have something to do with his end at DC? Or was it conflicts from working at National that provoked his emotional problems? The above splash from Western Comics #4 was among these final efforts. I am not sure how, but the Vigilante has somehow made the transition from a costume hero in the modern age to being a western genre hero.

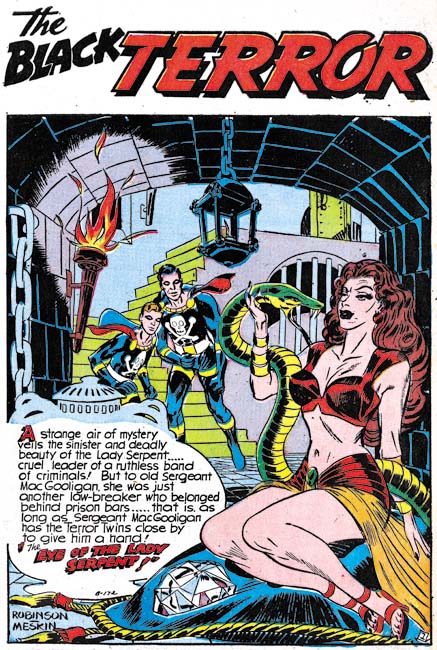

Black Terror #23 (June 1948) “The Eye of the Lady Serpent”, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

Robinson and Meskin were only teamed up for a relatively short time, a little over a year. I may not be clear as to exactly what each of the two artists contributed to the joint efforts, but whatever it was it certainly was very successful. I find the art as exciting as Mort’s early work for DC.

Black Terror #23 (June 1948) “The Eye of the Lady Serpent” page 5, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

It was not just the splashes that Robinson and Meskin did so well, the story art is also first rate. Note the inking on this page as particularly seen in the last panel. The long sweeping parallel lines would later play an important part of Meskin’s inking style. Even more interesting is the presence of picket fence crosshatching (see the Inking Glossary for explanations of the terms I use to describe spotting techniques). Similar inking can be found for a piece that Jerry and Mort did for Simon and Kirby (Young Romance #5, May 1948). The inking looks like it was done by Meskin, but did he pick up the picket fence technique from Simon and Kirby or is there an earlier Robinson and Meskin example that I have not seen yet?

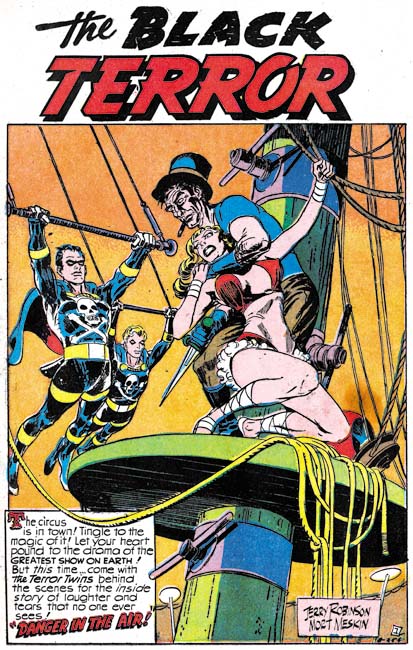

Black Terror #23 (June 1948) “Danger in the Air”, art by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin

Another great splash by Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin. I might not have anything to say about it but how could I resist including it in this post?

I previously used a story page from this work to show the style Mort had adopted for depicting punches.

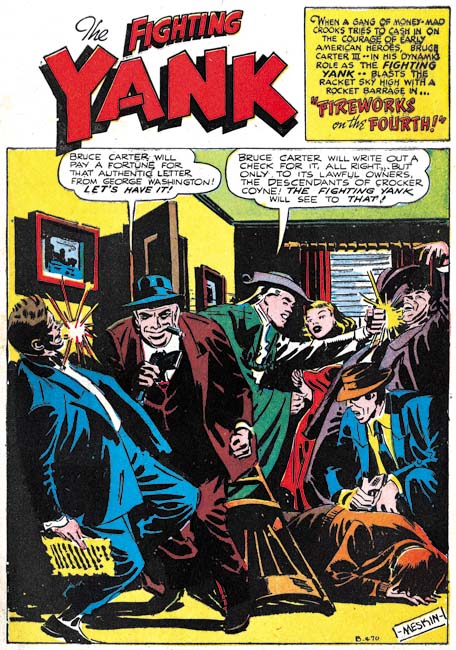

Fighting Yank #29 (August 1949) “Fireworks on the Fourth”, art by Mort Meskin

There may have been a relatively brief period between after the breakup of the Robinson and Meskin team where Mort was doing work by himself again but he had not yet started to work for Simon and Kirby. Fighting Yank #29 is signed by Meskin alone and Robinson does not appear anywhere in the comic. Mort’s first solo work for Simon and Kirby were cover dated December 1949 (Real West Romance #5 and Young Romance #16). Joe Simon has reported in The Comic Book Makers that initially Mort had an artist block. That Meskin was doing some solo work before joining Simon and Kirby may indicate that the artist block did not start until he actually began working for Joe and Jack. Perhaps intimidating presence of Jack Kirby had something to do with Mort’s artistic difficulties.

The “Fireworks on the Fourth” is inked in an interesting spotting technique. The blacks are grouped in a blocky fashion that to my eyes seems to flatten the image while providing it with interesting patterns. This is not the result of a bad printing; other stories by Meskin in the same issue are not inked in this manner.

Fighting Yank #29 (August 1949) “Fireworks on the Fourth” page 7, art by Mort Meskin

The effects of this unusual inking can be best be seen in the story itself. While it is possible that this inking was done by another artist, I believe it was Mort’s own work. He would use a similar style of inking for a period later for some Simon and Kirby productions.

In a few months Mort Meskin would begin working for Simon and Kirby. Mort would become an important and prolific artist for Simon and Kirby productions. He did not, however, work exclusively for Joe and Jack. Meskin would also provide work for other Prize comics and occasionally other publishers as well.

It seems to me that Meskin’s syle must have been a big influence on Ditko.

It’s funny, but while I’ve always really liked Meskin’s work, your last couple of posts are persuading me that if anything I’ve been wildly underrating him. He’s even more remarkable than I thought!

Harry, another great posting, beautiful art and wonderful insights. Also, I don’t think I had seen your descriptions of inking technique, just brilliant.

A few things to note: Jerry and Mort shared a studio for almost a decade. I can check the exact dates, but this continued while Mort was at S & K. Even if they didn’t always credit each other, they were at the very least influencing each other right up through the mid 50’s, more than just the Vigilante, Fighting Yank, Black Terror period.

Since Mort worked with Kirby at Eisner/Iger and then with Joe and Jack at DC (along with Jerry) I doubt very much Mort was intimidated by Jack, nor that his presence would cause him any emotional distress. I’m still researching Mort’s emotional problems but I feel fairly certain that they weren’t the result his working at National nor had anything to do with lack of confidence in his artistic abilities.

Best,

Steven

Steven,

Are you sure about Meskin sharing a studio while at S&K? Joe Simon has stated a number of times that Mort worked at the S&K studio. There are photographs and other witnesses that give confirmtion.

However how long Jerry and Mort shared a studio is besides the point. So far I have only seen evidence of joint work for a relatively short period of time (a little over a year). They may have shared a studio and influence one another but that is different from working as a team.

Jack was at Eisner for a short time, was Mort there at the same time? As for the DC period, during most of it Joe and Jack worked at their own studio and not at the DC bullpen. It was only when Joe entered the Coast Guard that they gave up the studio and Jack worked for a little while at the DC bullpen before entering the army. But even though Meskin and Kirby had met earlier, it was a different relationship. At S&K it was not just a question of Jack’s talent, more importantly Jack had become Mort’s boss.

I did not say that Mort’s problems with DC had to do with lack of confidence in his own artistic abilties. Mort’s end at DC seems rather sudden. And I seem to remember reading somewhere that Mort had conflicts with one of the editors at DC.

Hi Harry,

According to Jerry they shared a studio (and for a time lived together with Bernie Klein) until the mid-50s. I’ve interviewed Jerry and have yet to transcribe, but can confirm the dates when I do. I will ask Jerry about collaborations past the late 40’s specifically, and also during the S&K period, although I am not questioning that Mort did indeed work in their studio. Still, Jerry told me they continued to collaborate throughout, up until Jerry started his comic strip. I am pretty positive Mort and Jack met at Eisner/Iger, but definitely Jerry told me that he sat in between the two at DC in the 40s bullpen.

As for his sudden departure from DC, sadly Mort has hospitalized with emotional problems, and after recovering he went to S & K. I believe the story of being treated poorly by the DC editor was from his second tenure at DC, ending in the 60s.

Robinson’s strip Jet Scott started somewhere in 1953. He did solo work for Stan Lee from 1950 or 1949, slowing down to lower number of pages from 1952. One thing you can see from the solo work of Robinson, is the fact that he used more lines. It seems as if Robinson was a penciller who could ink and Meskin an inker who could pencil. Or to put it more positively, Meskin was someone who could draw with a brush.

Correction… most of the Robinson stories I have for Stan Lee are in the crime books of 1951 and some of the war books of erly 1952, making it more probable that Robinson worked free-lance for Timely after the bullpen was disbanded in 1950.

I was thinking how much the inking on those last two Fighting Yank pages reminded me of Klaus Janson.

Steven,

Oral testimony is valuable evidence, but that is all it is. People’s memories are subject to failure, especially after so many years. For questions like how long artists collaborated, the proof is in the pudding. That is it is the comic books themselves that provide the best evidence.

Scott,

Klaus Janson? Never occured to me before, but then again I am not very much up on the more modern comic artists.

Defining shapes, particularly faces, by their shadows is something Klaus Janson does more than any other modern inker. Only the last story in this blog entry is done that way, though, suggests to me that Meskin varied his style widely or had little involvement in his own inking.

Scott,

Thanks for the observations about Klaus Janson. I’ll have to check him out.

Yes the inking for “Fireworks on the Fourth” is pretty unique amoung the Meskin work from the period. Even some other Meskin stories in the same Fighting Yank issue do not share its inking mannerism. I purposely left the question of whether Mort inked it himself vague. I remember Meskin adopting a similar technique during his time of working for Simon and Kirby. If I am right a comparison should suggest if it was Mort’s inking.

Pingback: Stranger than Fiction: When Comics tell only half a “True Story” – downthetubes.net