For the 2013 Best Picture Oscar-winner Argo, Jack Kirby’s Lord of Light artwork was omitted and his crucial role in the CIA’s rescue plot was downplayed and distorted, but that is only a part of the problem with the film.

…History cannot be swept clean like a blackboard, clean so that “we” might inscribe our own future there and impose our own form of life for these lesser people to follow.

—Edward Said

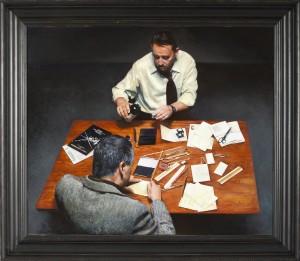

“ARGO – The Rescue of the Canadian Six” (artist unattributed)—CIA’s Intelligence Art Gallery

Ben Affleck’s film Argo embodies the racism that Western governments display towards the peoples and governments of the East that Edward Said described in his groundbreaking study, Orientalism. Argo re-envisions for dramatic effect a covert escapade that occurred at the same time as the Iran Hostage Crisis in 1979: a joint USA/Canadian operation in which CIA operatives disguised six American diplomats as a movie crew to rescue them from where they were hiding in Iran in the homes of Canadian diplomats. For this successful mission, the CIA implemented an elaborate deception that appropriated a proposed film adaptation of Roger Zelazny’s Hugo award-winning novel Lord of Light, which featured a spectacular series of set designs drawn by famed comic book artist Jack Kirby and inked by that artist’s most faithful and accomplished finisher, Michael Royer.

Due to the inherently covert nature of the operations of the Central Intelligence Agency, the events surrounding the rescue are still enmeshed in a web of misinformation, apart from what the agency released in 1997 when it declassified the mission. The film Argo furthers confusion through the imposition of familiar devices of suspenseful storytelling. Argo is constructed as an entertaining adventure narrative, but the production condescends to depict a generic Middle Eastern world. The film achieves a degree of tension, but along the way, it alters many details and adds major narrative elements in order to amplify the drama, most of which also either demonize, infantilize or otherwise provide a derogatory impression of the Iranian people. It valorizes an American ideology, minimizes the crucial Canadian contribution to the saving of American lives and changes key points about the original film proposal for “Lord of Light.”

Dissemination is celebrated throughout Argo. The covert deceptions of the CIA are presented as appropriately linked to the fictions of Hollywood. The second half resembles an “Indiana Jones” epic as it deviates from actual events to show how the clever, resourceful and decent Westerners outwit the primitive and gullible heathen Easterners. Even the depiction of the hero is a predictable example of Hollywood racism: the film’s Caucasian director, Ben Affleck, dies his hair and wears a beard to portray Antonio Mendez, the ingenious Hispanic CIA agent who accomplished the operation.

_______________________________________________

Oddly, Argo begins well. The faux-documentary introduction gives an accurate if abbreviated account of the suffering of the Iranian people under the corrupt excesses of Shah Mohammad Rezā Pahlavī. In 1953, England’s MI6 and the CIA deposed Mohammad Mosaddegh, the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran, who had nationalized the country’s oil, removing it from British control. Subsequently the Shah of Iran was placed in power and became known for his conspicuously extravagant lifestyle, while his people starved. The violent methods of control of his regime, including the torture and murder of his opponents, resulted in his overthrow in January of 1979 by Islamic fundamentalists, led by the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. When the Shah travelled to America to seek cancer treatment, Iranians demanded his extradition. On November 4 1979, Iranian students seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and took 66 Americans as hostages, a violation of international diplomatic law. The students accused the embassy staff of being CIA operatives and justifiably so: Mendez confirmed that at least one of the hostages held in the US embassy was a CIA agent I .

However, in the film the straightforward account of the reasons behind the Islamic Revolution is directly followed by clichéd views of mobs of enraged and insensible rioters, images that align with the Orientalist view of Eastern society which Said details, that is “…always shown in large numbers,” and represents “…mass rage and misery, or irrational (hence hopelessly eccentric) gestures. Lurking behind all of these images is the menace of jihad” (287).

There are many scenes throughout the film that depict crowds, in the airport and on the street, as masses of alien “others,” either suspicious, fearful or enraged. The images of roiling crowds imply threats to America that are presented as an illogical, irrational mob. The depictions suggest that any and all members of Middle Eastern culture will react with a surfeit of emotion. The threat to the West is therefore amplified because it does not operate within systems of American logic. It is counter to the rational aims of governing Christian principles.

The violations of diplomatic immunity in the Iran Hostage Crisis were labeled by the United States as “terrorism” and used to justify whatever actions Western powers subsequently took against Iran, including the imposition of crippling sanctions. “Diplomatic immunity” refers to reciprocal policies that are customarily held between governments, to ensure that at all times, including times of conflict, diplomatic personnel can be free of prosecution under the host country’s laws and that they may travel freely between countries in their pursuit of diplomacy.

Subsequently to the embassy takeover, thirteen of the African American and/or female hostages were released, but the remaining 52 hostages were held for 444 days. Not included in the film, but certainly part of the political climate at the time were several failed attempts at resolving the protracted crisis, including the disastrous “Operation Eagle Claw,” in which eight servicemen and several aircraft were lost, that were believed to have caused President Jimmy Carter’s loss of the 1980 election to Ronald Reagan. It is also documented that Republicans prolonged the hostage negotiations in order to affect the outcome of the election, a subterfuge called the “October Surprise.” The hostages were finally released through an accord brokered by Algeria on January 20 1981, the day after Reagan was sworn into office.

On the same day that the hostages were seized, November 4 1979, six diplomats escaped from the U.S. embassy through the back door and were hidden in the residences of two Canadians, ambassador Ken Taylor and diplomat John Sheardown. Over the following months, Canadian and American officials considered various means of delivering the six “houseguests” safely from danger. Finally, on January 28 1980, the six fugitives were spirited out of Iran in the guise of a film crew visiting the country scouting for locations, accompanied by CIA operative Mendez and his colleague “Julio.” The film Argo supposedly dramatizes this basic narrative.

The movie proposal that the CIA appropriated to be the subject of their bogus production was Lord of Light, an ambitious project that allegedly fell into stasis after it hit some legal snags. Mendez has stated that the Lord of Light was a “defunct production” when John Chambers gave the CIA the script, but actually its problems began at the same time that the CIA made their use of the materials. The promotion for Lord of Light appeared in the trade papers The Hollywood Reporter and Variety in November of 1979, as the Iran Hostage Crisis began. A month later in December of 1979, the same Hollywood periodicals showed ads and articles about the CIA’s proposed production, renamed “Argo,” and their front company “Studio Six.” After the CIA’s mission began, Lord of Light foundered.

According to producer Barry Geller, he began work on the Lord of Light project in 1977 to capitalize on Hollywood’s new-found interest in science fiction epics, due to the recent success of Star Wars. On his website, the self-described “time traveler” says that his purpose was “to bring attention to our extraordinary mental powers just as Star Wars brought recognition of life in the galaxy.” Geller wrote the screenplay as an adaptation of Roger Zelazny’s Hugo award-winning novel and he hired comic book innovator Jack Kirby to do conceptual drawings for the film’s set, the structures of which would also perform double duty as a science fiction-themed amusement park. Geller claims he gathered a brain trust for the massive and complex undertaking that included architects R. Buckminster Fuller and Paolo Soleri, video game pioneer Gary Gygax, author Ray Bradbury and Oscar-winning film makeup artist John Chambers. It is known that Chambers occasionally used his skills to aid the CIA.

In a scene that was widely shown and celebrated in the promotional push for Affleck’s movie, Geller is portrayed as a sleazy Hollywood huckster, Max Klein (played by Richard Kind) who is coldly swindled out of the rights to his manuscript by the slick and condescending producer Lester Siegel (played by Alan Arkin), under the auspices of Mendez and the CIA. In contrast to the depiction, Geller says there was no interchange between himself and anyone connected with the CIA, other than Chambers, and that at the time, he was unaware of the makeup artist’s intelligence connections. Geller says that Chambers simply provided his script and graphics to the CIA for their purposes, without permission.

Geller’s project has problems with credibility, too. It seems unlikely that a film production could afford the resources to build any sets to the safety specifications and requirements necessary for a family theme park. Movie sets are typically built to be facades, properly viewed only from the vantage of the camera and meant to last for only as long as needed for the film production. For this reason the amusement park is implausible. Geller claims it would have featured not only user-friendly versions of the huge and elaborate buildings and vehicles designed by Kirby, but also massive revolving holographic projections (technology that scarcely existed at the time II ) and a floating half-mile-high geodesic dome.

A scene in Argo that deviates significantly from actual events is the one that depicts a promotional press event in Hollywood arranged by the CIA where actors in costume do a reading of the script for “Argo.” a scene dramatically cross-cut with shots of the hostages taken in the U.S. embassy tortured by being forced to face a bogus firing squad. This misrepresents the actual press event that was held by Geller in Aurora, Colorado in November 1979 announcing a funding drive for the “Science Fiction Land” amusement park, with football player/actor Rosey Grier, Geller’s second in command Jerry Schafer, Chambers and Kirby in attendance. The land deals for the site of the park in Colorado and the legal proceedings that accompanied them landed Schafer and some Colorado politicians in prison. Some journalists who reported on the Science Fiction Land debacle for the local Colorado press continue to depict Schafer and Geller both equally as con-men III. But by literally every other account, Geller was cleared of charges and he denies knowledge of the CIA’s use of his proposal before he heard of the declassified mission when a PBS television show First Person aired a segment about Mendez in 2001.

Geller’s explanation for the failure of his initial proposal for Lord of Light and the theme park raises some flags:

We got to the point where someone put down the first $10 million, which was in the bank, and I’d optioned 1,000 acres of land in Colorado for the park. That’s when the government stopped everything. I was in the process of talking to directors and scientists, and the money was there. It was something that….it had the attention of many, many people and it was just unfortunate (Morrow, 25).

It would seem that “the government” had ample reasons to derail Geller’s plans. Whatever the feasablity of his proposal, the enmeshing of his project in a legal morass cleared the way for the CIA’s usage of his promotional materials. The idea that Lord of Light was undermined by a deliberate subterfuge on the part of the intelligence agency is supported by the documented involvement of John Chambers in both of the concurrent uses of the materials by Geller and the CIA and by the proximity of the promotional timeframes.

________________________________________________________

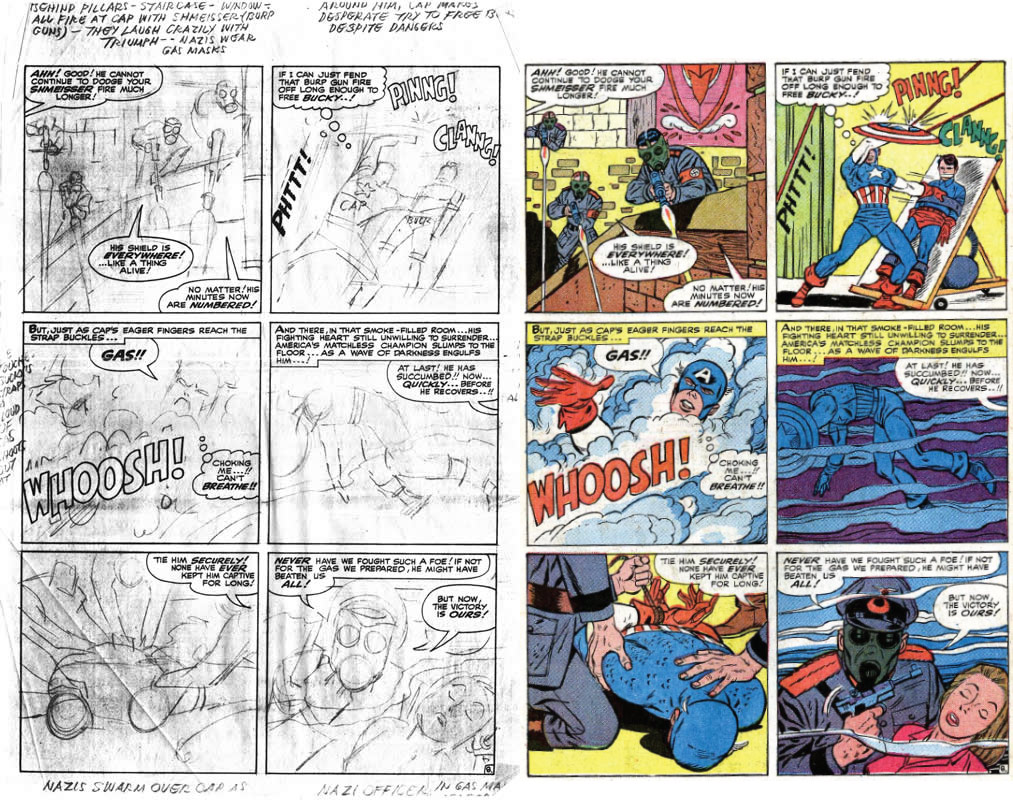

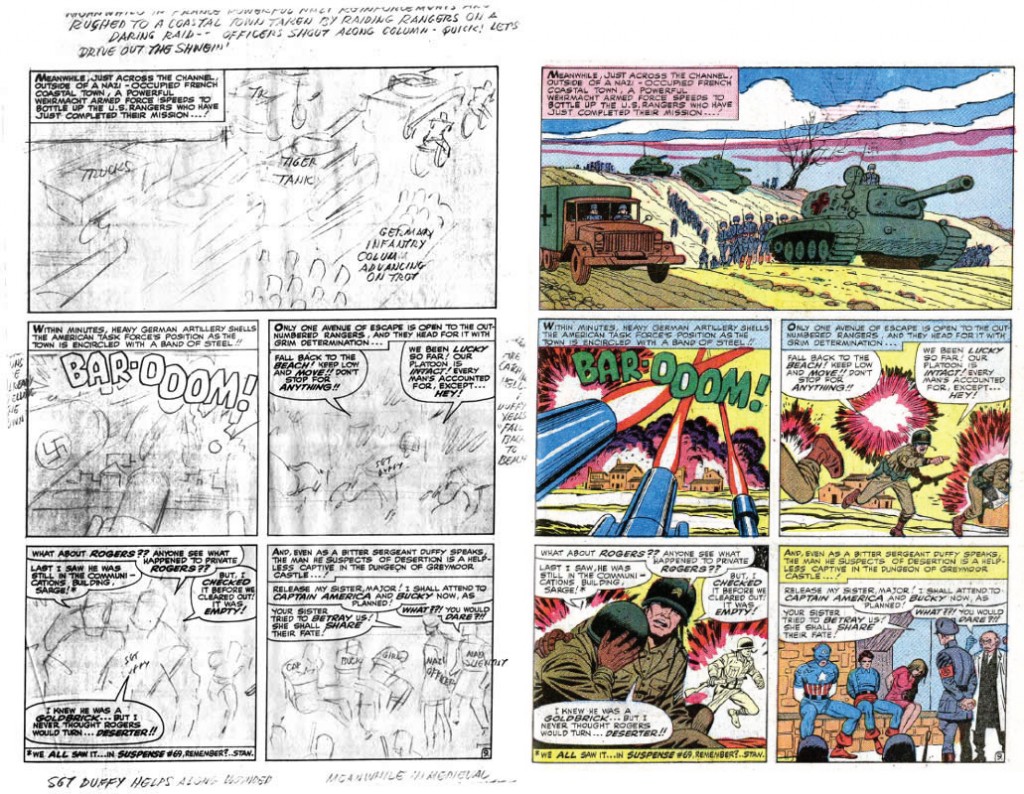

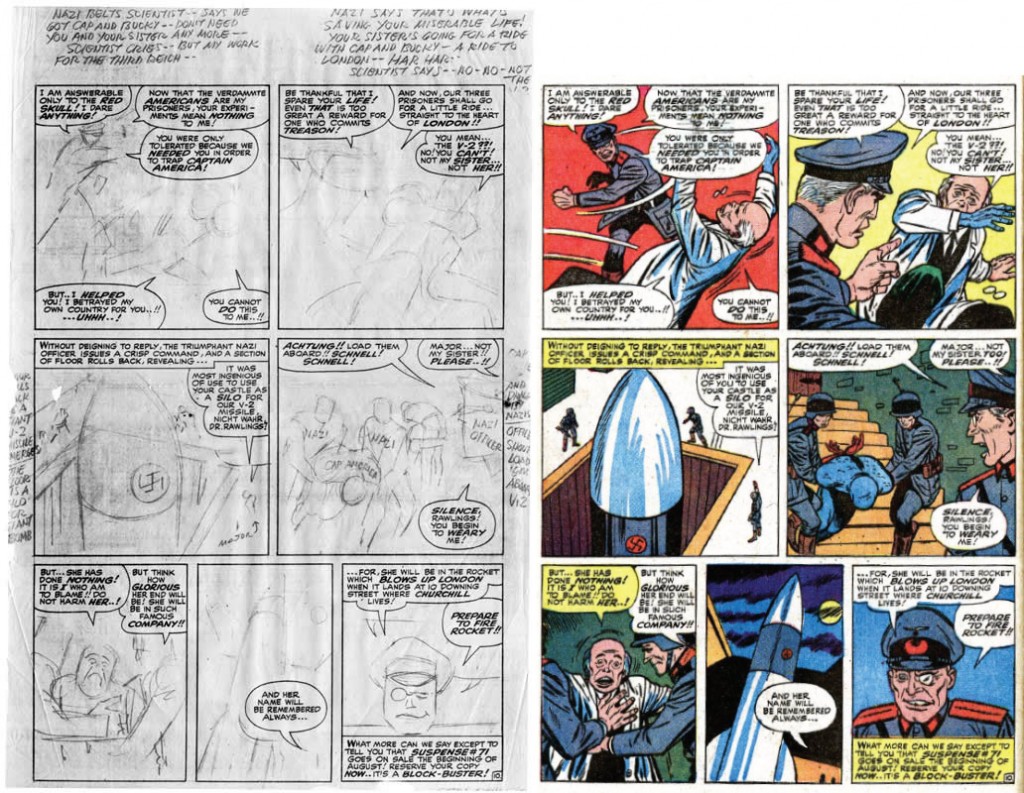

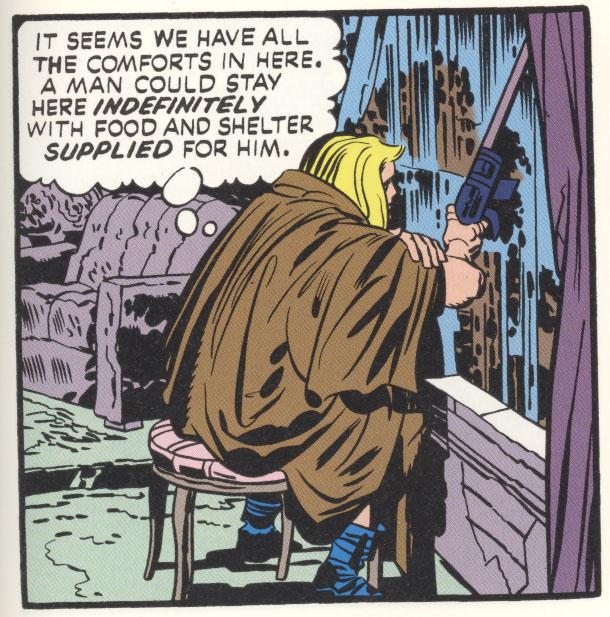

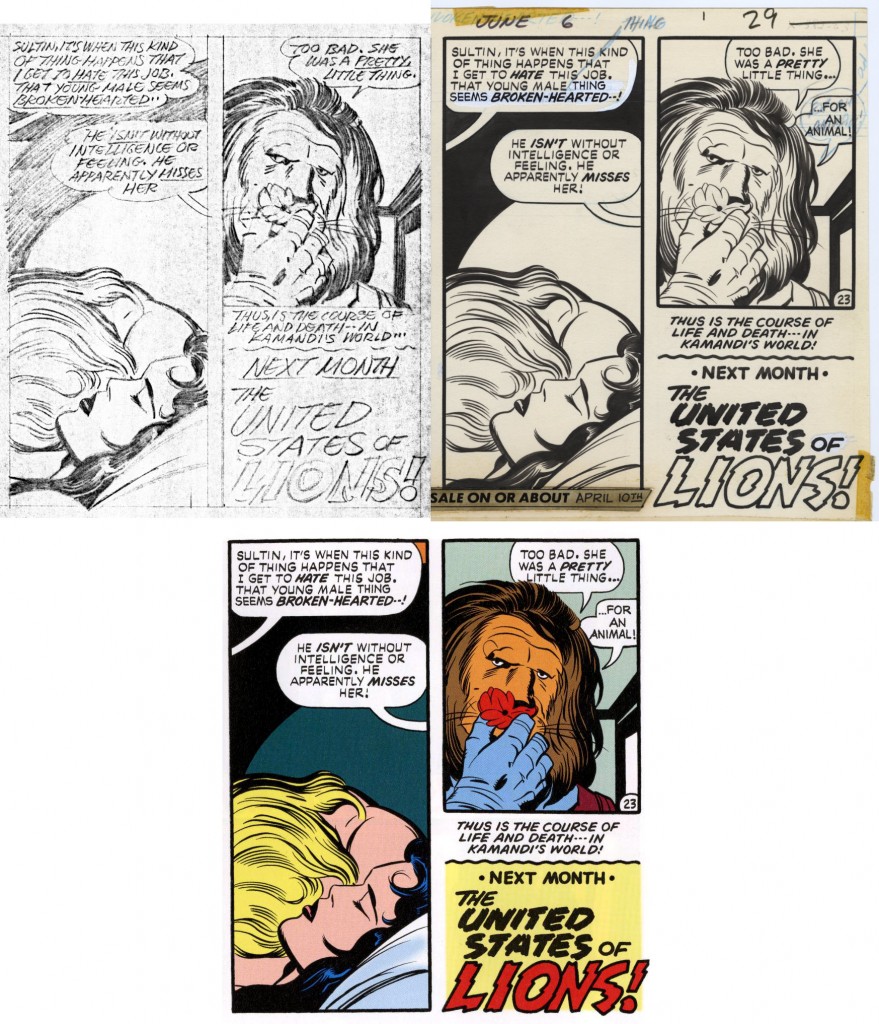

The importance of the artwork in the planning and execution of the CIA’s rescue mission cannot be overstated. Kirby’s original drawings were so impressive that they gave the operatives and the escapees confidence that the plan was plausible. Everyone involved believed Kirby’s art would convince the Iranians of the project’s legitimacy and further, it was drawn within stringent Islamic cultural rules of what may be depicted according to religious law. All of these considerations were set aside when the needs of the Argo filmmakers to satisfy an American audience were at odds with the appearance of the actual drawings. Further, how much involvement and knowledge that Kirby actually had of the CIA’s plan, at the time or at any rate, before it was declassified, is unclear.

According to Geller, in 1978 he hired Kirby, a famous and prolific comic book artist noted for his incredibly inventive imagination as well as for his speed, to do a series of conceptual architecture drawings that would serve as the basis for both the film sets and the design of the theme park. In a career that spanned a half-century, Kirby created many comics characters that in recent years have been featured in films that have grossed more than $7 billion. Although Kirby has often been credited as a creator of these properties in the films, his heirs receive no compensation. Corporations own the characters Kirby initiated as a freelancer. His Marvel heroes such as The Avengers, X-Men, Fantastic Four, Captain America, Thor, SHIELD, etc. are owned by Disney and his DC Comics 4th World/New Gods are owned by Time/Warner, the parent corporation of Warner Brothers, the producers of Argo. For this reason, one would have thought that it was in Time/Warner’s interest to promote the brilliant WWII veteran Kirby as a significant contributor to this patriotic mission. But, no.

At first, Affleck’s Argo production did seek to use Kirby’s actual drawings in the film. Randolph Hoppe, curator of the Jack Kirby Museum explains:

The Kirby Museum was originally contacted late in June 2011 by Warner Brothers’ Permissions & Clearances staff, who were urgently asking for permission for the Lord of Light images. I pointed them to Barry Geller’s email address. A week and a half later, I was contacted by a producer of the movie who told me the Lord of Light images weren’t going to be used as they “didn’t read well on screen.”

Kirby’s actual large signature images are not shown in Affleck’s film. Instead, the film shows banal storyboards drawn by other artists. Kirby’s drawings, though, have other factors that made them essential to the plot: they seem calculated to appeal to an Islamic sensibility. They are ornate and linear without modeling, the human figurative presence in the art is minimized and flattened and most of the drawings are done from the vantage point of an overhead “minaret view,” in a manner remarkably similar to ancient Islamic tapestries IV ). According to Geller, he rejected only one of Kirby’s pieces: a watercolor entitled “The Streets of Heaven,” which depicts a majestically ascending Godlike figure, shown from a ground level vantage. Otherwise, Kirby’s drawings are much more appropriate viewing for Muslims such as the Iranian airport security guards seen at the end of the film than the more figurative storyboards used in the movie, which are instead calculated to signify to American audiences who are familiar with Star Wars.

Kirby’s images are indeed complex and appropriate for the Iranian audience, but since his art might have needed explanation of the nature of its intended impact on Islamic viewers, rather than tax the short attention spans of the American audience, the producers say they opted for simpler, more easily identifiable visuals. The drawings used on screen do not resemble Kirby’s work in any way; rather they are spare, crudely rendered sketches. Still, the art figures so prominently in the film that its impact on the characters seems to be in inverse proportion to its quality. In Mendez’s account and as depicted in the film, his idea of using a fake movie production crew to extract the hiding diplomats didn’t seem feasible until the agents hit on the Lord of Light promotion package. Kirby’s work is impressively well done and suits the purposes of the CIA exactly. It is clear that the artwork added greatly to the credibility of the film proposal, for Geller’s purposes and for the CIA administrators who approved the rescue mission, the personnel charged with accomplishing it and the diplomats who had to participate in their own rescue, whether or not the Iranians saw it.

It is not clear why Affleck’s production completely diverges from the historical record to show the CIA hiring Kirby, and further, it shows the artist being coached by an operative to make the backgrounds of his drawings more exotic. It is alleged that footage was shot of “Kirby” adding minarets and domes to his “storyboards” so they would be more convincing to the Islamic security forces, a scene that was left on the cutting-room floor. Actor “Christian Christian” said that he was cast as a “hand double” for Michael Parks, the actor hired to play “Kirby” onscreen. Christian claims that wrinkles and age spots were applied to his hands several times and he was filmed drawing additions to the “storyboards” (Richards (in a comment below the online article)). Such scenes display ignorance of Kirby’s working process, since he would not have amended his drawings in such a way, but would probably have had to re-pencil the relevant portions and then pass the amendments along to inker Mike Royer to complete and incorporate into the final images.

Hoppe says that he was again contacted by Argo’s set decorating department in August 2011:

…they said they’d arranged with the Kirby estate to use Kirby’s name and work, and were looking for items to use on the set of the Kirby home. I showed them some work via the web and never heard from them again. Kirby’s home was not used, the IMDB listing of the actress who’d been cast as Jack’s wife Roz Kirby was changed to “Office Manager.”

These reversals may have come about because the rights to Kirby’s drawings are owned by Barry Geller, rather than the Kirby family and an agreement with Geller was not made. The alteration in the circumstances of Kirby’s employment may be a liberty on the part of Affleck’s production; on the other hand, it might not. The multitalented Kirby worked for U.S. military intelligence in World War II; he functioned as a reconnaissance artist used to sketch out the positions of Axis forces on the front lines in France. Other cartoonists of Kirby’s generation who were in the services, such as Alexander Toth and Will Eisner, kept contacts in military circles and later made their talents available to the government when needed V ). Kirby passed away in 1994 without clarifying his role in the Lord of Light/Argo events and evidence that he knew of Mendez’s plan remains anecdotal. Kirby’s friend and biographer Ray Wyman claimed to the author that several years before the death of Kirby’s wife Rosalind in 1998, Geller told her about the CIA’s plot. Wyman said, “John Chamber’s name had been bandied about…How would Barry have known that the CIA was involved, since the thing wasn’t revealed until 1997?” (Romberger & Van Cook, 17). Wyman also reported that he saw the “Argo” poster made by the CIA at the Kirby home in a closet, and said that Kirby told him of other incidents that indicated that he had fans in the CIA.

If Barry Geller’s account is true, he was a hapless victim of circumstance, or even of a fraudulent persecution by the government so they could appropriate his proposal—but any which way, the closeness in time of the two usages of the materials is troubling. It might be considered that to date we must rely on only Geller’s account of the initiation of the Lord of Light/Science Fiction Land projects and for the timeline of when the drawings were actually completed. It could be speculated that the art may have been done closer to the time of the Iran crisis—-and that if, as the movie depicts, Kirby was actually hired by the CIA, or even by Geller acting as some sort of a CIA proxy, it could have been because of not only the quality of his imagination, but also his speed. Kirby certainly was able to produce drawings of such complexity to order very rapidly and his inker Mike Royer was likewise quick and prolific. As well, Kirby oddly worded his statement in the promotional package that Geller assembled to secure funding: “I believe that this film and the way we are conceiving it could contribute to saving the world” (Morrow, 27). This is a heady claim for a sci-fi film, connected theme park or not. But in the end, perhaps it is better for Kirby’s reputation that his work was left out of Argo, because the movie is so tainted by racism.

_________________________________________________________

Some of the changes made to the account of the rescue by Affleck’s production seem done for the purposes of storytelling expediency, such as that the fact that the “houseguests” were actually split into two groups that hid in several Canadian diplomats’ residences was altered to being only one group hiding with Taylor. Argo also eliminates the second CIA operative, “Julio” and adds the contrived character of producer Lester Siegel, one supposes for reasons of streamlining, or to move the story along. However, other alterations are more disturbing.

Most of the representations of the events in Iran shown in the second half of the movie are fictitious. There is a long and extremely fraught sequence where officials from the Iranian department of film development call Mendez and demand that the fake production crew meet with them in a public marketplace for the purposes of witnessing their scouting for locations. What follows are is a tense series of scenes where Mendez’s van filled with the six vulnerable masqueraders encounters a fundamentalist street demonstration. When he is unable to back up because there is another mob coalescing behind them, Mendez drives the van through the center of the angry group of shouting demonstrators, who shake the vehicle and hammer on the windows. They miraculously pass through, shaken but unharmed. They go on to meet with the Iranian officials and then they are shown to be terribly fearful as they walk through the marketplace. When one of the party, in trying to stay in character, inadvertently takes polaroids of an older man without his permission, the group are threatened with violence by a crowd. How they escape is not explained. However, the point is moot because these scenes are created for theatrical effect. The film’s fictional status is frequently at odds with its pseudo-documentary staging. Both the advertising and the promotional materials surrounding the film give the strong implication of truth, of the unmediated narration of historical events and the valorization of American actions in the execution of the operation.

The climactic scenes of Argo are comprised of more tension-building sequences that have little or nothing to do with actual events. In fact, there was no reversal of the go-ahead to proceed with the mission at the 11th hour, which the stoic Mendez had to hide from the group; there was no incommunicado Presidential press secretary and no withholding of ticket authorization by the president until the last possible minute. According to Mendez’s declassified report, other than that he overslept by a half an hour on the day they were to leave Iran, there was no holdup at all: reservations were secured and tickets had been purchased well in advance. Nor was the L.A. “Studio Six” office foolishly and prematurely closed by the CIA before the mission was accomplished. These incidents were invented to pile on dramatic suspense.

Further and importantly, the immigration officers did not check to make sure that the exiting “film crew” had matching white and yellow forms and the security forces did not pull the band of escapees into a side room to check their cover story. In Mendez’s account on the CIA’s website, he says that no one looked at Kirby’s artwork: “the Iranian official at the checkpoint could not have cared less.” No soldiers had to have the narrative of the “Argo” proposal explained to them and nobody called the “Studio Six” offices to confirm Mendez’s claims. Nor did Iranian soldiers attack Swedish Air hostesses or throw other female passerbys around the terminal, raid the airport traffic controller’s tower or drive their jeeps and police cars at breakneck speed after the departing aircraft. These scenes, which depict frightening Iranian/Arab security forces and the abuse of women, are intended to alienate the American audience from the demonized enemy. Within the logic of the Hollywood movie there must be bad guys and good guys, there are no shades of grey. The characters must be easily identifiable. The problem with this theatrical logic when applied to the dramatization of historical events is that ideological positions become polarized into moral oppositions. These in turn seamlessly validate the audience desire to be on the side of the righteous.

The urban landscape of Iran is shown to be barbaric and forbidding, a land where vehicles burn on the streets and men are lynched from construction cranes in intersections. The film imbeds overt indicators of racism, as when Mendez says at the beginning, “If these people can read or add…pretty soon they will figure out they are six short of a full deck.” Later, the official at the Iranian “office of communication” asks Mendez if he is seeking to represent “the exotic orient—snake charmers.” As well, he responds amenably to Mendez’s mistaken exit salutation of “salaam” which is the Eastern equivalent of “hello.” Affleck plays the urbane Mendez as if he is sophisticated enough to be aware of local etiquette, but does not care enough to respect his adversary. He does not care to learn their language, despite his engagement with their culture. The movie Mendez views Iran (which prior to its Islamic Revolution was an ultramodern society) to be as Said describes the American view of the East: “backward, degenerate, uncivilized and retarded…analyzed not as citizens, or even people, but as problems to be solved or confined or—as colonial powers openly coveted their territory—taken over” (207). The cumulative effect of the repetition of negative stereotypes and representations of the citizenry as unruly mobs of less intelligent people seems to justify the need for them to be treated as “problems to be solved.” In Argo, the real life drama can also be unraveled by the superior wits and courage of the American forces. For the audience who experience this onscreen conundrum, since the stakes are never any higher than the cinematic depiction of the past, the outcome confirms their self-belief in their intellectual superiority as members of the victorious team, as if by right.

According to Mendez’s account, when he first met “the six,” they had managed to keep their spirits high and were excited to be part of his scenario. He briefly mentions that one of them had some initial reservations, but hastens to say that any discomfort was rapidly dispelled by his manner and various means he had at his disposal to put them at their ease. In the film, the balker is revealed to be “houseguest” Joe Stafford, but his fearfulness is exaggerated so that he is shown to have protracted reservations throughout the process. He doubts Mendez’s commitment and honesty; he holds back on learning his cover identity until the last minute; he refuses to join them on the outing to the market. To placate Stafford, Mendez reveals his real name and relates a few personal details, after which Stafford relents and climbs into the van. Thereafter, he is no longer negative about the plan, but in the end he violates the restrictions Mendez made on their cover story and endangers them all by speaking Farsi to the suspicious security forces at the airport, to enact the narrative of the storyboard to them. This action, however, ends up saving the day. And then finally, in the plane as they realize that they succeeded in escaping, Stafford comes to Mendez to offer a belated handshake—but, these scenes too are all fabricated.

It is these final, false scenes which comprise the most racist aspects of Affleck’s film. The head of airport security is shown as stereotypically rude and chauvinistic Mid-Easterner; a swarthy, popeyed and aggressive man who makes a guttural interrogation of Mendez’s band. This character, designated in the credits as “Azizi Checkpoint #3” and portrayed by Farshad Farahat, exemplifies the Orientalist view described by Said and seen in the media as:

associated either with lechery or bloodthirsty dishonesty. He appears as an oversized degenerate, capable, it is true, of cleverly devious intrigues, but essentially sadistic, treacherous, low…The Arab leader…can often be seen snarling at the captured Western hero and the blond girl….“my men are going to kill you, but—they like to amuse themselves before.” He leers suggestively as he speaks (286-287).

Said’s comments are made explicit in the way Argo depicts how “Azizi Checkpoint #3” inquires if the woman depicted in a skintight outfit in the painted “Argo” ad in the issue of Variety proffered by the group (no such painted ad ever was created) is escaping “houseguest” Cora Lijek. Even when told that she is not, he persists in a lewd and suggestive manner.

By the demands of their cover story as Canadians, none of the escapees are supposed to be able to understand anything but English or French, but in order to placate the security officer, the multilingual Stafford uses pidgeon Farsi to tell him a narrative for the proposed film in a patronizing manner. In reality, Kirby’s artwork would not have sustained the narrative that Stafford describes, which was invented for this version of “Argo.” However, in the film, Stafford pulls out the storyboards and boils the plot of the ostensible film down into simplistic terms that he thinks the security officer will understand, which the English-speaking viewer reads in subtitles:

Alien villains have taken over the hero’s planet. They fight for their families and take back the city. The villains know he is the chosen one, so they kidnap his son in the spice market. So he and his wife storm the castle…the people are inspired to join him. They are farmers but they learn to fight. And the king of the aliens is destroyed when the people find their courage.

Stafford’s ploy seems to be working and the enactment degenerates further as he gestures with his hands in swooping movements, while verbally making childlike sounds of swooshing rockets, zapping raygun beams and explosions that evoke the universally-recognized soundtrack of Star Wars. After this display, “Azizi Checkpoint #3” turns out to speak and understand English after all, but presumably because he and his fellows warm to the reference to “farmers,” he allows the group to proceed. By hiding that he is multilingual, he reflects the “cleverly devious” image of the Easterner cited by Said. Then, Mendez gifts the younger members of the security detail with a few of the storyboards, who proceed to make childlike noises of a space battle, in imitation of Stafford’s infantilizing but successful presentation. None too soon, the group boards the plane, but Affleck amps the suspense with a superfluous chase scene that is reminiscent of the climax of a cheap B-movie set in a banana republic.

Edward Said’s assessment of the overall agenda of the American mission in the Middle Eastern world, as indicated in the quote used above as an epigraph, remains valid. The deceptions of Argo ensure that the American audience can relate to the film, but they have a greater resonance than just that of a stimulating entertainment. Widely viewed and praised mainstream films such as Argo affect public opinion, they influence public acceptance of the foreign policy decisions of whatever U.S. administration is in charge at any given time. The awarding of high honors, an anointment at the Oscars that was introduced by no less of a personage than the First Lady, to a film that displays so many instances of misinformation about a culture that we do not appreciate or understand, does not contribute to the peaceful resolution of conflict. As Argo was made and released and as it won its Oscars, the United States was engaged in a dangerous exchange with Iran about its nuclear capabilities. Affleck’s film, even though about a situation decades in the past, has been promoted, disseminated and honored in such a way that it has influenced the American public’s perception of Iran and the rest of the Middle East and so, it has beyond a doubt continued to promote negative attitudes towards our current engagement with that region of the world.

____________________________________________________

Thanks to Marguerite Van Cook and Professor Giancarlo Lombardi of CUNY Graduate Center.

____________________________________________________

Footnotes

I. Mendez wrote in his account of the escape on the CIA site: “The Iranians, moreover, had embarrassed the US by finding a pair of OTS-produced foreign passports in the US Embassy that had been issued to two CIA officers posted in Tehran. One of these officers was among the hostages being held in the Embassy.”

II. The most advanced technology for displaying holograms at the time is described thus:

In 1976 Victor Komar and his colleagues at the All-Union Cinema and Photographic Research Institute (NIFKI), U.S.S.R., developed a prototype for a projected holographic movie. Images were recorded with a pulsed holographic camera at about 20 frames per second. The developed film was projected onto a holographic screen that focused the dimensional image out to several points in the audience. Two or three people could see a 47 second movie in full dimension without glasses. Kormar’s plan to scale up the process for a 20 to 30 minute film for an audience of 200 – 300 people never materialized.

—-Source: http://www.holophile.com/history.htm

This does not account for a huge exterior display at the top of a building that would be visible from all points around it, such as the one above the “Brahma’s Supremacy” structure that Geller describes in the interview I conducted with him.

III. A 2012 article on Denver Westword entitled “Science Fiction Land could have been Aurora’s biggest tourist trap, if its backers weren’t crooks” by Melanie Asmar ignores the fact of Geller’s exoneration to claim that:

Schafer and Geller’s lies soon caught up with them. On December 14, 1979, the Rocky reported that Schafer had been arrested for securities fraud. Local authorities claimed that he and Geller had “convinced an immigrant who speaks only broken English to give them his life savings — $50,000 — to help finance the park,” the Rocky reported. An arrest warrant had been issued for Geller too, but he’d “left the country.”

—-Source: http://blogs.westword.com/latestword/2012/04/science_fiction_land_aurora.php

IV. A good part of my limited understanding of the permissible imagery parameters of Islamic art is gleaned from Orhan Pamuk’s novel My Name Is Red (Trans. Erdag M. Goknar. New York: Vintage International, 1989), where he explains that in ancient Islamic illuminations, a linear quality and flattened perspective are used to satisfy a religiously ordained requirement of flatness, a two-dimensionality imposed so art would not presume to God’s view, seen as sacrilegious in the full-perspective and chiaroscuro realism of European art. This is further elaborated upon in Aniconism and Figural Representation in Islamic Art by Terry Allen:

The traditional Muslim theological objection to images, which may have been observed more in the breach than in ordinary life, was eventually codified in a quite rigid form and extended to the depiction of all animate beings. It is captured in the prediction that “on the Day of Judgement the punishment of hell will be meted out to the painter, and he will be called upon to breathe life into the forms that he has fashioned; but he cannot breathe life into anything…. In fashioning the form of a being that has life, the painter is usurping the creative function” of God.

—Source: http://www.sonic.net/~tallen/palmtree/fe2.htm

Most of Kirby’s Lord of Light drawings simulate the elevated “minaret view” that is standard in Islamic illuminations, described in the Wikipedia page on Islamic art as:

…a birds-eye view where a very carefully depicted background of hilly landscape or palace buildings rises up to leave only a small area of sky. The figures are arranged in different planes on the background, with recession (distance from the viewer) indicated by placing more distant figures higher up in the space, but at essentially the same size.

—Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_art

V. For information about Toth’s post-service work for the Armed Forces in the 1970s, see Genius Illustrated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth. Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell. San Diego: IDW Publishing, 2012, pages 192-196. Eisner’s decades of work for the U.S. Army are documented in PS Magazine: The Best of The Preventive Maintenance Monthly. Will Eisner. New York: Abrams Comic Arts, 2011.

____________________________________________________

Bibliography

Argo. Dir. Ben Affleck. Perf. Ben Affleck, Bryan Cranston, Alan Arkin. Warner Brothers, 2012. DVD.

Geller, Barry Ira. “The CIA, the Lord of Light Project and Science Fiction Land.” Lord of Light. Web. 22 May 2013. http://www.lordoflight.com/cia.html.

Hoppe, Randolph. “Argo/Lord of Light.” Message to the author. 22 May 2013. E-mail.

Mendez, Antonio J. “A Classic Case of Deception: CIA Goes Hollywood.” Central Intelligence Agency, 14 April 2007. Web. 18 May 2013. https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/winter99-00/art1.html.

Morrow, John. “Seeking the Lord of Light: Interview with Barry Ira Geller.” The Jack Kirby Collector #11. July 1996. Print.

Richards, Ron. “Jack Kirby, ARGO & Jim Lee: A Hollywood Legend.” iFanboy: 23 October 2012. Web. 22 May 2013. http://ifanboy.com/articles/jack-kirby-argo-jim-lee-a-hollywood-legend/.

Romberger, James and Marguerite Van Cook. “Kirby, the CIA and the Lord of Light: Interview With Barry Ira Geller” & “Eyewash: About Argo.” Comic Art Forum #2, Winter 2003. //kirbymuseum.org/blogs/effect/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2013/02/LordOfLight-RombergerVanCook2002_sm.pdf.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vantage Books, 1979. Print.