Previous – 4. 1940, The Year Of Living Furiously | Contents | Next – 6. Love, Betrayal, And The Rumors Of War

We’re honored to be able to publish Stan Taylor’s Kirby biography here in the state he sent it to us, with only the slightest bit of editing. – Rand Hoppe

MAKING IT PERSONAL

From the very first issue, Captain America had been a smash. It was soon selling a million plus copies per issue. It became Timely’s best seller, and Cap its most prominent character. Simon and Kirby had produced something unique.

Captain America was neither a Boy Scout, nor a dark detective and his tales were not little morality plays. They were violent clashes between good and evil, with no concern for nuance or moral equivalency. The decision to use Hitler as the central villain demanded that the crimes be realistically evil rather than theatrical scene chewing, and the heroics had to be equally driven. From the very first story the villain murdered a scientist, saboteurs blew up and killed innocents, and the Red Skull assassinated military personnel. Captain America was not designed to bring these criminals to justice, or to help bad people change their ways. Cap was not a cop; he was created to destroy this evil, to wipe it off the face of this Earth. Cap did not debate the morality of an eye for an eye, or worry about the philosophical ramifications of his actions, his job was to affect an almost Biblical retribution on those who would destroy us. Captain America was an elemental remedy to a primal malevolence. He was Patton in a tri-colored costume.

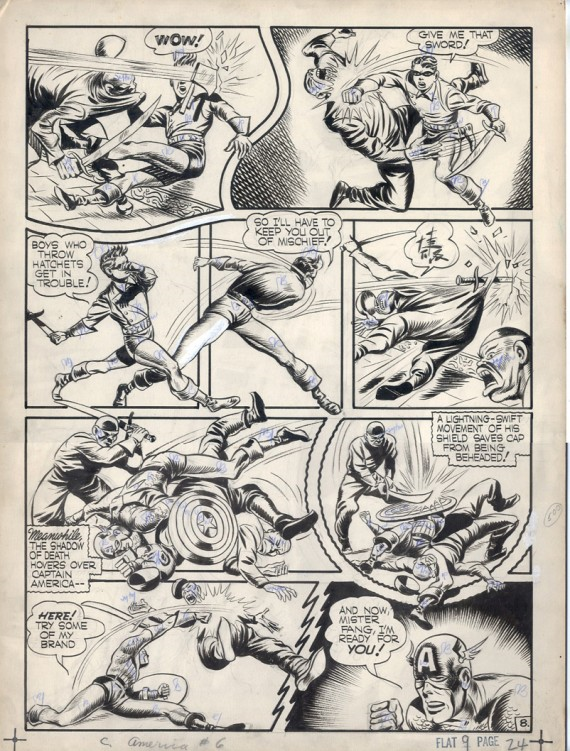

Rare original art Cap #6

Captain America wasn’t bloodthirsty, just single minded, and if that meant being judge and jury, so be it. Admittedly, it was rare that the villain died directly by Cap’s hand, usually it was the result of an evil scheme gone wrong, or an ironic reversal in a planned demise meant for Cap. It wasn’t even that every villain was killed in the end, but whether they were or weren’t, never bothered Cap one way or the other. When the German spy is killed at the end of the origin chapter, Cap nonchalantly remarked, “A fate he well deserved”– no remorse, no questioning. In the Red Skull’s first appearance, after he is unmasked and defeated, the Skull makes one last desperate attempt at escape and Bucky tries to stop him. While Cap stood motionless, the Skull rolls over on a hypodermic filled with poison and dies. Bucky gets up and looks at Cap incredulously and asks, “But you saw it all–why didn’t you stop him from killing himself?” To which Cap casually replied, “I’m not talking Bucky” In one tale Cap dispatched a villain with a well thrown tusk broken off a dinosaur skeleton, and another died when knocked out of the sky by Cap’s shield. Captain America wasn’t Roy Rogers shooting a gun out of a bad guy’s hand, and turning him over to the sheriff. Cap was 007 with a license to kill, leaving a body count that would impress Dirty Harry. Of course, no one really cared, Joe and Jack made sure that the villainy was so ghastly, and the action so breath-taking, that the deadly force seemed the justifiable outcome.

If Captain America was the perfect physical specimen- the super-soldier- than Bucky Barnes was every little guy with a dream of smashing in the face of the bully. He was a scrapper, a perpetual motion dynamo, taking them on five and six at a time and never backing down. He was Jack Kirby’s alter ego. When asked by Will Eisner if the heroes were fighting in his (Kirby’s) mode, Jack explained. “I felt that if I had to fight 10 guys, I’d find a way to do it.” This was Jacob Kurtzberg paying back every taunt and slight he had endured for being the runt. This was Jack Kirby confronting the strong arm goon in Will Eisner’s office. This was Jack Kirby making it personal.

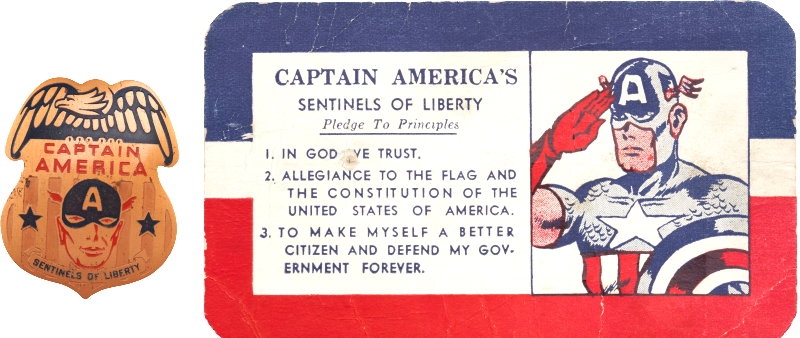

The Holy Grail of comic merchandise

To some Jews, there was a different interpretation.

More from Rabbi Simcha Weinstein and his book, Up, Up and Oy Vey!:

Despite the patriotic appearance, Captain America’s costume also denotes deeply rooted [Jewish] tradition. Along with other Jewish-penned superheroes, Captain America was in part an allusion to the golem, the legendary creature said to have been constructed by the sixteenth century mystic Rabbi Judah Loew to defend the Jews of medieval Prague. “The golem was pretty much the precursor of the Superhero in that in every society there is a need for mythological characters, wish fulfillment. And the wish fulfillment in the Jewish case of the hero would be someone who could protect us. This kind of storytelling seems to dominate in Jewish culture,” commented Will Eisner.

According to tradition a golem is sustained by inscribing the Hebrew word emet (truth) upon its forehead. When the first letter is removed, leaving the word met (death) the golem will be destroyed. Emet is spelled with the letters aleph, rem and tav. The first letter, aleph, is also the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet, the equivalent of the letter A. Captain America wears a mask with a white A on his forehead- the very letter needed to empower the golem.

Jack would revisit the Golem mythology later.

Despite the gruesome undercurrent, these books weren’t grim. They were filled with humor, and light hearted slapstick, and over the top action. This was real stuff, and the consequences were often real, but this was also comic books, and the reality had to be presented in an overly melodramatic and visually exciting manner. If the good guys were costumed super heroes, than the villains had to be just as impressive, and even more visually stimulating. Issue #1 introduced not only Cap and his little buddy Bucky, but also the baddest arch villain of all time. The Red Skull was a sadistic sociopath and as drawn by Jack, a great visual image of pure evil. With his leering smile, burning eyes and blood red visage, he constantly taunted the boys. His goal was not to unmask Captain America, or humiliate him -Simon and Kirby had no use for typical comic book super-hero clichés- the Skull’s aim was to kill Captain America and destroy the U.S. As with all great fictional antagonists, no matter how many times he died, he was just too evil, and too huge to stay dead. He would reappear with great regularity throughout the series long run.

With characters that intense, the art had to keep up. In strips like Blue Bolt, and the Vision, Jack had experimented with exaggerated figures, and extreme action, but nothing prepared the comic reader for the explosive power found on Cap’s pages. Jack literally created his own physical dynamic, not based on human mechanics, or realistic proportion or actual range of skeletal movement, but from Jack’s hyper sense of how a scene needed to be exaggerated for maximum effect. When characters ran, they ran with legs impossibly apart and bent at inhuman angles. Yet they were always balanced and graceful, and when they fought, it was epic. Kirby’s figures never jabbed, or feinted, every punch was thrown from the heels, with the body twisting and torquing for maximum impact. Once hit, the recipients didn’t fall back or down, they flew oftimes completely out the panel.

Jack told Will Eisner how his technique evolved. “It’s (fighting) something that is an extreme form of behavior, and I had to do it in an extreme manner. I drew the hardest positions a character could get into. So I had to get my characters in extreme positions, and in doing so I developed an extreme style which was easily recognized by everybody.”

Jack’s fight scenes were violent ballets of body parts and sweeping movement. The idea of maximum impact was something Jack had absorbed at Fleischer where Popeye’s fights with Bluto were exaggerated to entertain. Jack knew instinctively that super heroes needed that extra cartoon dimension of power and exaggeration to actually make visual sense. If a Superman hits something, the response couldn’t be like a human boxer, the reader needed a different visual iconography to understand the extreme power these heroes represented. Cartoon style histrionics provided the perfect visual template. Jack told historian James Van Hise; “I had a fighter on my hands (Captain America) and I had to make him look like a fighter. You have to see a player from all angles and having an animation experience helped a lot because I put a lot of movement into my figures…..that was a big help in the kind of work I was doing. It made my figures move. It set a style for me which everybody recognized.”

The speed that was demanded didn’t allow for Jack to research and draw realistic machinery, so tanks, planes and guns took on an abstract nature. Kirby told Eisner; “I had no time to put fingernails on fingers. I had no time to tie shoes laces correctly…..I just made an impression of these things. In other words, I would draw a tank, it would look like a German or American tank, but that’s where it ended.”…”No detail, I didn’t have time to do it.” Backgrounds and machinery were important, but detail and factual minutia actually slowed down the reading process and distracted from the storytelling. Kirby’s constructs had mass and a functionality that was immediately obvious. They were loud, gaudy and impossible, and always dramatically impressive. At a later date, it would be called Kirby-tech, but in 1941, it was just Kirby following his storytelling instincts.

Simon wasn’t just a by-stander as Jack grew and experimented. Joe was experiencing his own growth spurt, laying out the covers, and composing the splash pages. Many of the design aspects on those covers and splashes evolved from Joe’s work in the pulp magazines; the figural posing and the title design and blurb placements are traits Joe would return to time and again. The splash page had traditionally been a glorified first page of the story, with a title added on, but in Captain America, they became stand alone little vignettes- presenting the reader with a premise. It was a cinematic prelude to draw the reader in and set a tone. In the same way that a movie trailer sets up a promise of suspense and excitement, the Simon and Kirby splashes became a trademark guarantee of an exciting story. S&K even began using panoramic double page splashes, the like of which had never been done before. They challenged the reader with varied angles, from panel to panel, changing perspective and view point. It was the equivalent of a constantly moving camera, not allowing the reader to get bored with a static POV. Everything was designed to maximize the reading experience by approximating cinematic techniques to control pace and build tension.

They were also experimenting with page and panel formats. Though Jack and Joe were never slavish devotees of the 3 over 3, or 3 over 4 rectangular grids, they had rarely wandered far from a rectangular panel, but from the very first pages of Captain America we see circular panels, and arched or s-shaped gutters between the panels. We see figures outside of the borders on almost every page. Not just to emphasize a main figure, but more to break up a straight line. It could just as well be a hand, or an arm, or a newspaper or some inanimate object. They were trying to elicit a feeling of movement by forcing the eye of the reader to flow from panel to panel, rather than the start and stop of separate panels. Jack literally didn’t want to be boxed in. Kirby explained to Will Eisner, “I tore my characters out of the panels. I made them jump all over the page. I tried to make that cohesive so it could be easier to read.” As the series went on, the borders would become even busier with zigzags and lightning bolt effects. The pages sometimes looked like jigsaw puzzles with the panels interlocking. The circular panels went from small inserts to full panel size, and at times overwhelmed the design. By issue #5 the circular panels came with scalloped edges.

Crediting inkers on Captain America is tough. Joe and Jack took their turns, but were helped by Syd Shore, Als Avison and Gabriele, Arturo Cazenueve, Charles Nicolas, Reed Crandall. Even Mort Meskin. Simon says Al Liderman helped on issue #1. Gil Kane says that Kirby was by far the strongest inker. “Simon only inked a fraction of what they did. Jack was his own best inker, he was superb. He did most of the Captain America splashes.”

The stories were formulaic, but they expanded beyond the “just the red meat” template of Colonel Jacquet. The premises were often ripped from recent movies. Plot elements from movies such as Lost Horizon, Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hounds of the Baskervilles, and Mad Love (aka Hands of Orlac) would find their way into Cap’s tales. Logic was not a requisite, but the characters were interesting, and the locales varied and action was always a page away. In one of the better stories, Jack took his never finished Wilton of the West meets Hollywood tale and remade it as a medieval period epic. Private Steve Rogers and Bucky Barnes are hired as extras in a Hunchback of Notre Dame like film. During the filming, a horrific murder occurs and while sniffing around, they uncover a Nazi plot. Between the jousting, the storming of a castle, and a sword fight the equal of any Douglas Fairbanks movie, the action never stopped. Jack’s rendition of the castle architecture and the period clothing are right out of Hollywood Design 101.

With the introduction of the Ringmaster of Death and his carnival of crime in issue #5 Simon and Kirby would produce another theme that would echo time and time again in their books.

In another interesting twist, one story ended with the battle weary twosome fast asleep in their cots catching some zzzz’s. The next story turns out to be a fairy tale dream by Bucky reminiscent of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and ends with the two waking up from their slumber. A nice bit of continuity and an imaginative way to get a lighter toned imaginary tale mixed in. This would feature Jack’s first full page spread showing Cap and Bucky hoisted on the shoulders of the happy townsfolk whose king had just been freed. They would also break the third wall and have characters speak directly to the reader, inviting them into the story.

Jack and Joe took from every influence they had absorbed and twisted and turned and melded this into a style so individualistic, so readily recognizable, that they had surpassed their influences. The students became the inspirers. Simon and Kirby became a brand. Will Eisner called Captain America, “Simon and Kirby at its purest. You started with an infant form and by sheer might-and-main created a whole new genre.”

The cancer was spreading; most eyes were on North Africa, where at last some good news emanated, an Italian garrison at Tobruk was falling to the Australian 6th Division. Half a world away, Adm. Yamamoto of the Japanese Imperial Navy was proposing a secret plan called Operation Hawai’i- a sneak attack on the island of Oahu, to catch the American Naval base at Pearl Harbor sleeping. On January 27th, the American Ambassador to Japan, William Grew sent a coded cable to President Roosevelt informing him of a rumored surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The rumor was quickly discounted. The U.S. of A. was still neutral–at least officially. No one told this to Jack and Joe.

In Feb. the team began production of Captain America #5. For the first time, a story was located in the Pacific. Call it prescience, or coincidence, but it seems that Capt. Okada of the Japanese Imperial Navy had a secret plan to destroy the Hawaiian island of Kunoa and catch the Pacific Fleet while they are in harbor. It is Cap and Bucky’s job to stop this insidious plot. While not as militarily impressive as Yamamota’s plan, a battleship swallowing sea serpent shaped submarine aiming to detonate a dormant volcano was pretty damn exciting, and a brilliant visual feast. Not only had Simon and Kirby launched a preemptive war on Germany, but now they were kickin’ “Jap” butt, ten months before Pearl Harbor. It also had a wonderful full-page cut-away view of the Japanese dragon ship.

Captain America was a sensation. NY Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, a regular comic strip devotee, called S&K personally to express his fondness for the strip. Amazingly, not everyone was happy with Captain America. On occasion the Timely office would get phone calls and letters from Nazi sympathizers threatening the creators of Captain America. Once, while Jack was in the Timely office, a call came from someone in the lobby. When Kirby answered, the caller threatened Jack with bodily harm if he showed his face. Kirby told the caller he would be right down, but by the time Jack reached street level, there was no one to be found.

Previous – 4. 1940, The Year Of Living Furiously | top | Next – 6. Love, Betrayal, And The Rumors Of War