An unexpected and wonderful rediscovery! I’m thrilled to finally share this insightful piece, written a decade ago by Richard Harrison, a multiple-award-winning poet, essayist, and editor, and a Professor Emeritus at Mount Royal University. The submission was originally sent to me by longtime Jack Kirby Museum supporter Steve Coates. Our deep gratitude goes to both Richard and Steve for their support and patience in its long-awaited publication. – Rand Hoppe, Jack Kirby Museum Director and Founding Trustee.

Based on the presentation for the panel “A Jack Kirby Influence,” at the Edmonton Comic Expo, September 26, 2015.

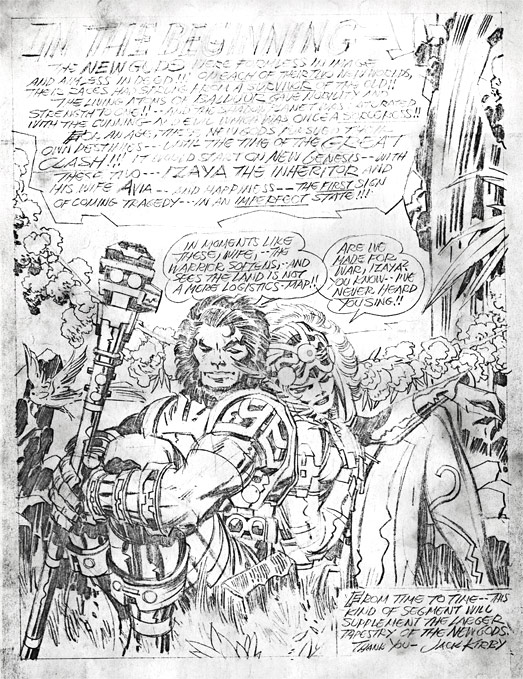

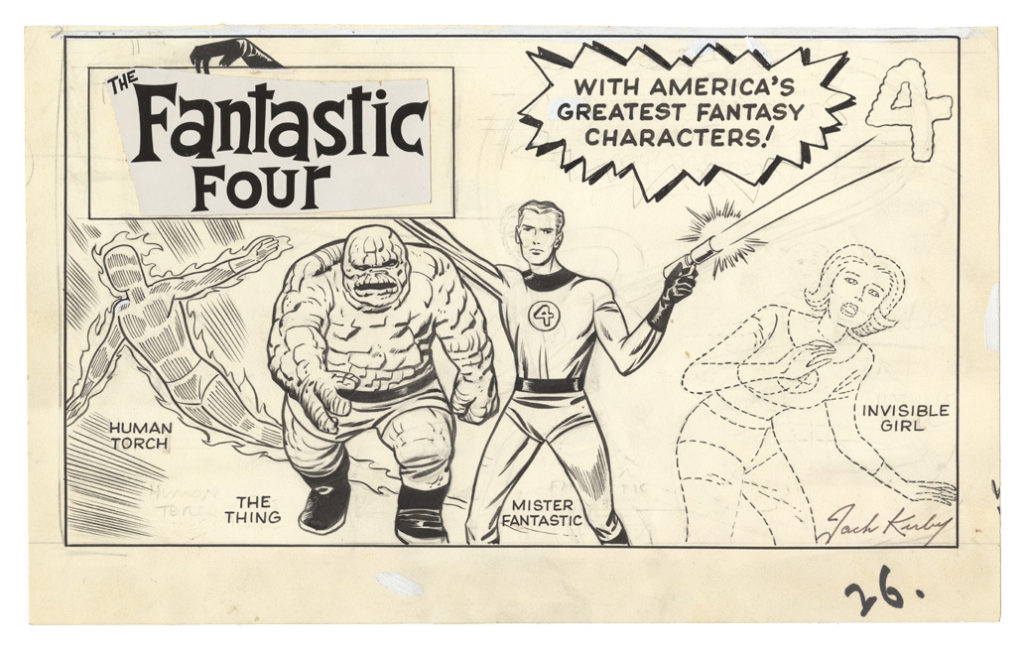

We all know the tremendous power and action within Jack Kirby’s art. And a lot has been written about the fascinating relationships between the visual and the personal in his characters. His graven idols – Galactus, Surtur, Odin, Hulk, the Stone Men of Saturn – did what they were supposed to do and inspired both awe and fear (if not in the reader certainly in the other characters) – and his heroes were tight-wound springs of muscle and purpose; Kirby was also fond of confounding our visual judgments by making the rock-skinned Thing the most emotionally fragile of the Fantastic Four, and the Deviant Karkas a sad Aristotle in an Elephant-Man’s body. Kirby gave us art like life: precisely when things are exactly as they look, reality is the opposite of appearance. This is one of Kirby’s great contributions: he drew life as paradox, a question that returns with every answer. His art was less a series of conclusions than it was his way of expressing his concerns, of inquiring into nature and the people around him. Indeed, in his 70th birthday radio interview in August of 1987 for Robert Knight’s show Earthwatch1, he says many times that what he was most interested in was studying people.

In one sense, certainly, Kirby’s work is a study of other people in the world (and God knows he was abused and loved by them for reasons that must have puzzled him his whole life). In another, his art is a study of himself. He said that, too. And I believe it.

But unless I’m missing something somewhere, Kirby was himself a shy man, a man of few words, at least in terms of public discussion of him and his work. You can hear it on YouTube in the Earthwatch tape, too. Verbally, he simplified what made his drawings so articulate. In the interview, Kirby turns down the chance to talk of himself as a visual artist, or a seeker; rather, he calls himself an entertainer, a performer instead. He expresses what he saw in himself less as a kind of drawing than as a kind of movement. He’s not wrong. His comics are movies you can hold, they are a stage show that I don’t think he ever saw ending, with some players in front of us for years and years, while for others, it was enter, do your bit, and exit, page right: Thousands of such characters, each of them with their own presence on the page. So the genius of Kirby lay in what he gave you to see.

And that leaves what we saw open to analysis and questioning. The question most important to me about Kirby started with what Art Spiegelman, another tower in the comics’ world, said of Kirby’s work. Of course, Spiegelman was meticulous and diminutive where Kirby was broad-stroke and gargantuan. Spiegelman wrote about characters whose best in the world was to survive it at all; Kirby was about those who never stopped fighting, who often won, who never had their dignity stripped from them, even in defeat. Both Kirby and Spiegelman understood the incredible levels of cruelty that humanity was capable of, but they took that knowledge in very different directions.

The comment, though, that Spiegelman made wasn’t about any of that difference. It was about how uncomfortable (my word) Kirby’s art made him. It’s clear that Spiegelman interpreted Kirby’s Mannerism (the exaggeration of gestures and body parts for effect) as crudity. Fair enough. But what he said was, “I suppose there’s something about Kirby’s sensibility, the optimism of it, that just puts me off. There’s an unpleasant exuberance, like a teenager chattering so excitedly he keeps spritzing you with his saliva.”2

To be fair, there were times when Kirby’s characters did spit, if not out onto the page, then in the way you could see the sweeps of saliva that stretched from floor to ceiling in the caverns of their mouths as they shouted in horror, combat, or rage. Of course, if you’re sitting close to the actors, they will spray you with their lines from the stage – and for a very good reason: they’re not talking to you, they’re talking to an auditorium.

For a long time, I wanted to reject Spiegelman’s comment. Kirby wasn’t a teenager, he was a grown-up man, a soldier, and he practically invented the action hero (before there was such a term) along with so much else, including the foundations of Marvel Comics itself. But I can’t argue that Spiegelman is wrong just because I didn’t like what he said when I read it. And now, now, I think he was onto something. Kirby’s art, for all its sophisticated exaggeration, is a child’s declaration of the way the imagined world is better than this one. Everything there is bigger, stronger, scarier, and more noble than it really is. And I think that that child-like quality to the work – the emphasis on fingers and hands and faces (which are the cues every child learns to look for to figure out the true nature of what’s coming for them) – that emphasis is what makes Kirby’s work so compelling. And not just to look at, but to inspire you to try for yourself.

And isn’t that what we say about art we think is easy? “My kid could do that.” But rather than seeing that as an insult, I think of it as praise. Of course, when the person who says that tries to make either the art in question, or the art “their kid could do,” they realize pretty quickly (or their viewers do. Or both) just how difficult it is to capture that spirit, that line, that shape. And yet truly great drawing encourages imitation; it makes us feel like whatever moved the pencil over the page for the original artist can move us too. Look how many artists either imitated or acknowledged learning from Kirby’s pencils or by drawing over his layouts: John Buscema, Don Heck, John Romita, Gil Kane, Herb Trimpe, and on and on. As Scott McCloud said of his work in his 1986 book Destroy!!:The Loudest Comic Book in the Universe, “I felt that almost all the artists in mainstream comics at the time were still playing ‘king of the hill’ with Jack Kirby… It was this whole collective Oedipus complex that everybody had, and I realized I had it, too! … I don’t think I was quite up to Jack’s strength. But … having done that, I felt I could move on … while a lot of my colleagues were still playing the game.”3

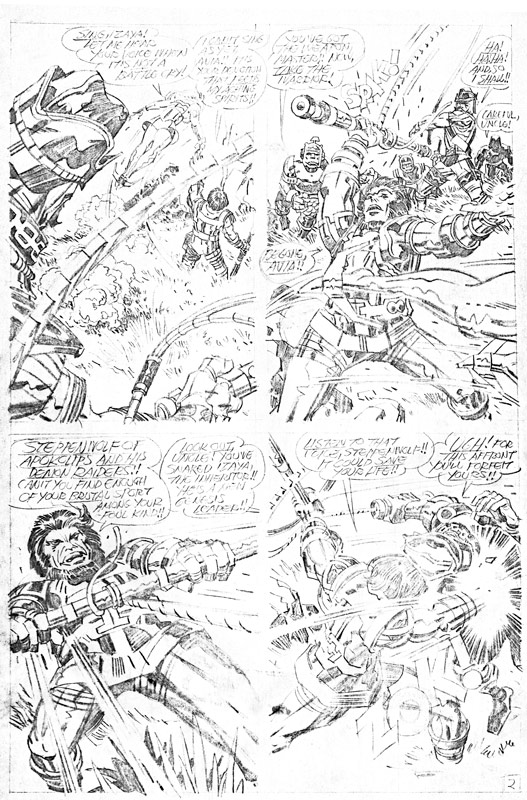

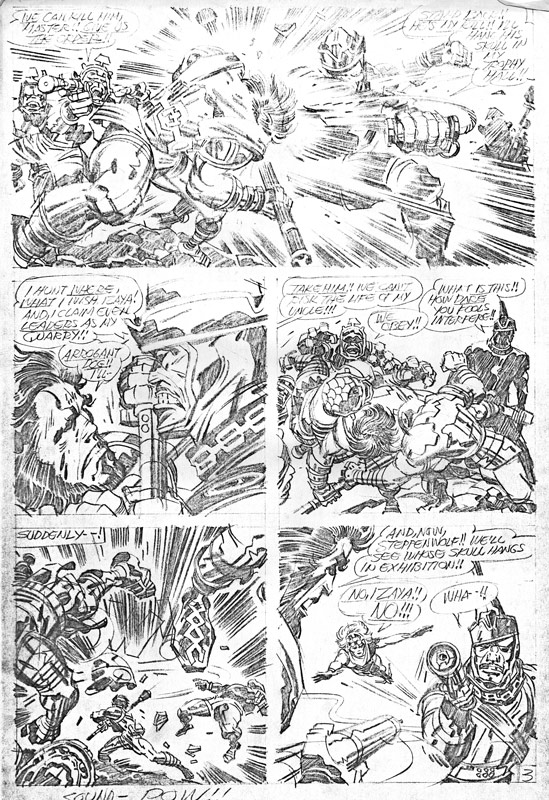

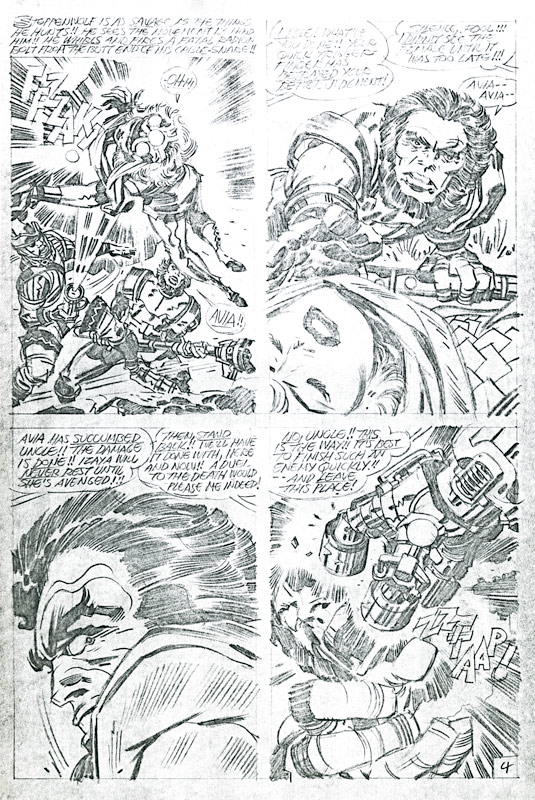

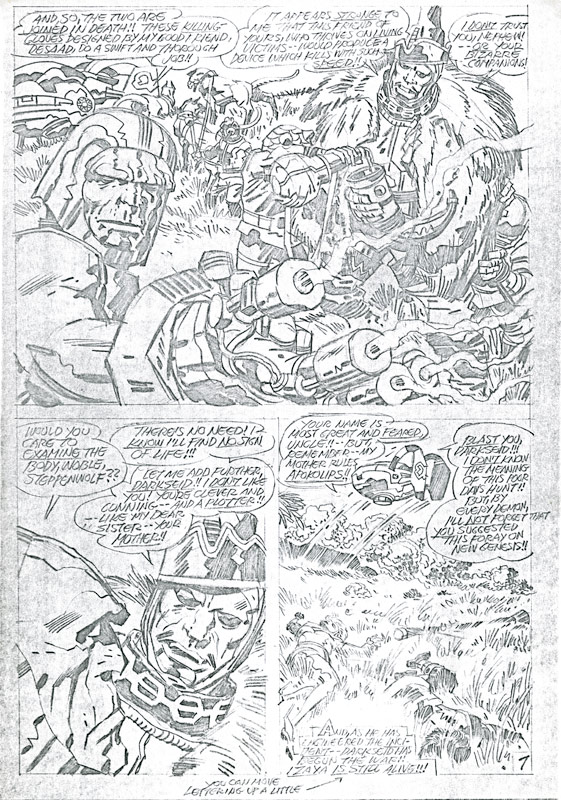

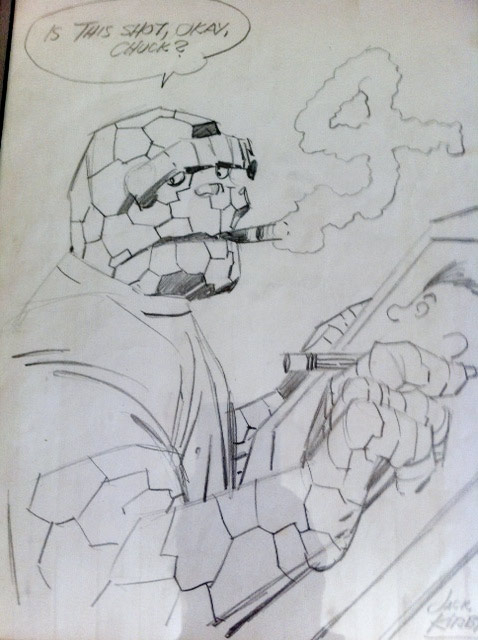

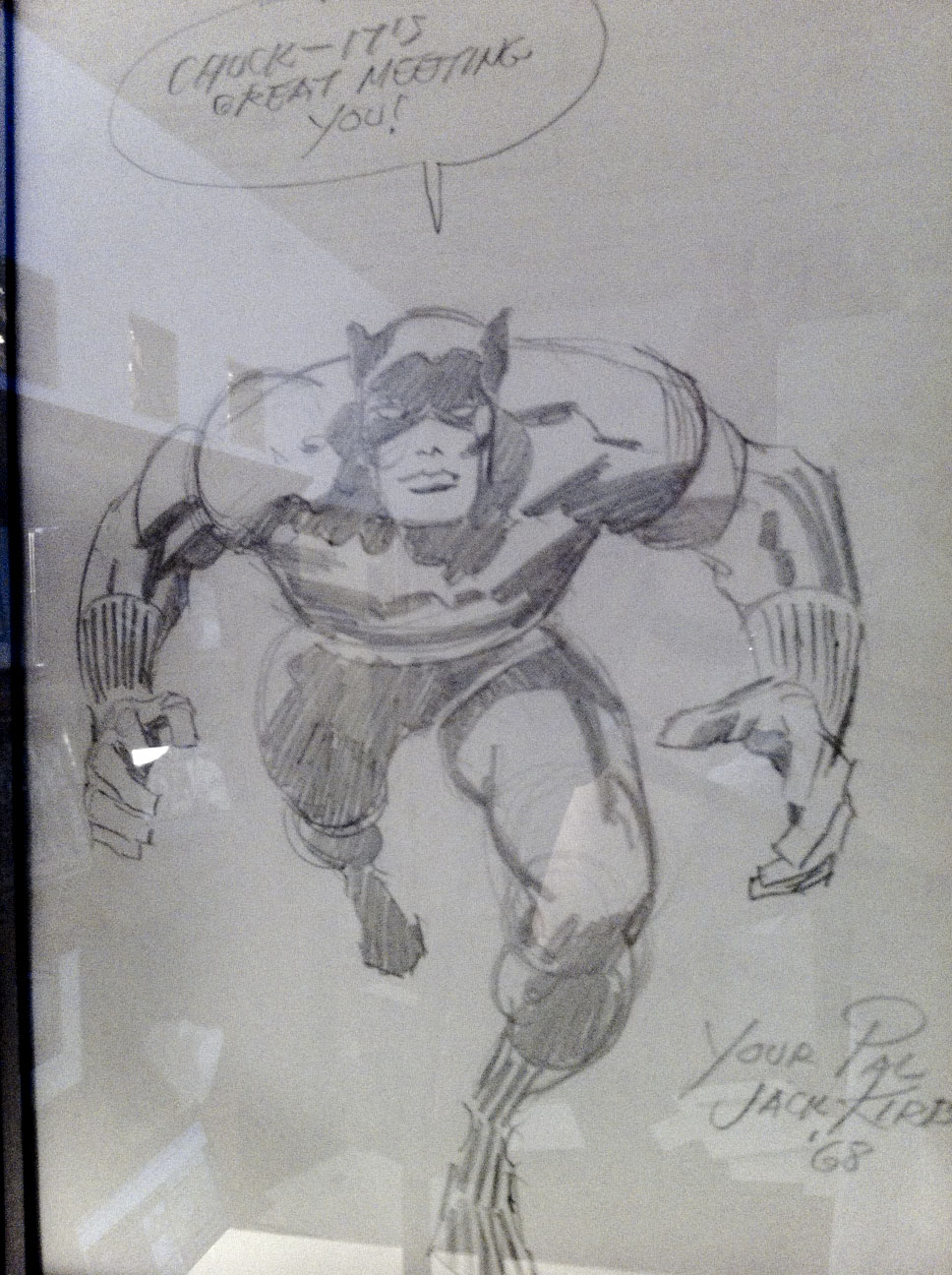

I agree. I’m only a hobbyist, but when I draw superheroes and villains and monsters for my own enjoyment, or as part of thinking about what to write about them, most of them Kirby creations – I know that I, too, want that power to well up through me and be present in my works. Through my own artistic reaching for those characters, I’m looking for the feeling I imagine Kirby to have had in bringing them to life. But I know all I get is only a glimpse.

No one else has done what Kirby did, and I don’t know whether what I’m thinking here is the reason for that or not, but after reflecting on Kirby as great power in my life, I came up with a poem (the art form which is closest to what I am) about Jack Kirby’s work. I’ll read it to finish, but I’m going to give away its argument, at least in part.

If art is “about” anything, I think Jack Kirby’s art is about hope – hope spoken through the language of action. His world, the comicbook world he helped create for 50 years, is a world where the story is this: there are saviours here on Earth, and they will save us in this life. Characters like that inspire by winning: Captain America, Iron Man, Thor, Ikarus, Orion, Superman. At their foundation, they are about overcoming the evils of the world, evils Jack also imagined or re-imagined with equal and lasting vividness: The Red Skull, Doctor Doom, Loki, the Celestials, Darkseid: villains so well imagined that they made their heroes great by their own stupendous malignance.

But I think Jack’s imagination, that balanced so well evil and good on the page, was hopeful because it also understood despair. Even from childhood – fraught with gang wars fought (so memorably in Jack’s mind and art) with fists and corncob missiles4 – through World War II and through again to his mistreatment at the hands of the industry he made possible – Jack was confronted with how hopeless things could be, how individuals could be cast aside or crushed by institutions and the machinery he dragged from the 19th Century into the fantastically imagined present and the far-flung future. In the end, I would argue, Jack’s art never lost touch with despair, or the causes of despair. Over the course of his extensive and loving biography of the man5, Mark Evanier often returns to the two Kirby nightmares that returned to haunt his sleep or that motivated his wakeful decisions: the first was not having enough to feed his family, the second was the War.

He may never have concluded anything, but I think Jack lived with a question that he drew over and over. When Jack invented Galactus, I recall hearing somewhere, that when he finished he was sweating at the drawing table; of the figure who, at the time, was Marvel’s most powerful, he said, “Galactus was God, and I was looking for God.”6 It was an act of creation he would repeat again and again. I think Jack invented God – and all His angels, rival deities, and mortal heroes – to answer the question his life put to heaven, one that every generation looks back and asks and thus finds echoed in his work: Where were You?

- “1987 – Jack Kirby’s 70th Birthday” Robert Knight (host). Earthwatch with Warren Reece and Max Schimd, and a call in from Stan Lee. Originally aired August 28, 1987 on WBAI. YouTube, accessed October 19, 2015, URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A1yJZKDwIRE ↩︎

- Quoted by Glen David Gold in Jeet Heer, “Jack Kirby: Hand of Fire Round Table. (Part One)” The Comics Journal. (April 30, 2012): np, accessed October 9, 2015. https://www.tcj.com/jack-kirby-hand-of-fire-roundtable-part-1/. / ↩︎

- Scott McCloud, “Understanding Comics” (Interview) Comic Book Rebels, ed. Stanley Wiater and Stephen R. Bissette. (New York: Donald Fine, 1993), 5-6. ↩︎

- Jack Kirby (writer and artist) “Street Code” (1983) reprinted in Mark Evanier. Kirby: King of Comics (New York: Abrams, 2008), 23-33. ↩︎

- Evanier, Kirby: King of Comics. ↩︎

- 6 Jack Kirby, “Interview by Gary Groth,” The Comics Journal 134 (Originally published February, 1990; Published online May 23, 2011):6, accessed, October 9, 2015. https://www.tcj.com/jack-kirby-interview/ ↩︎

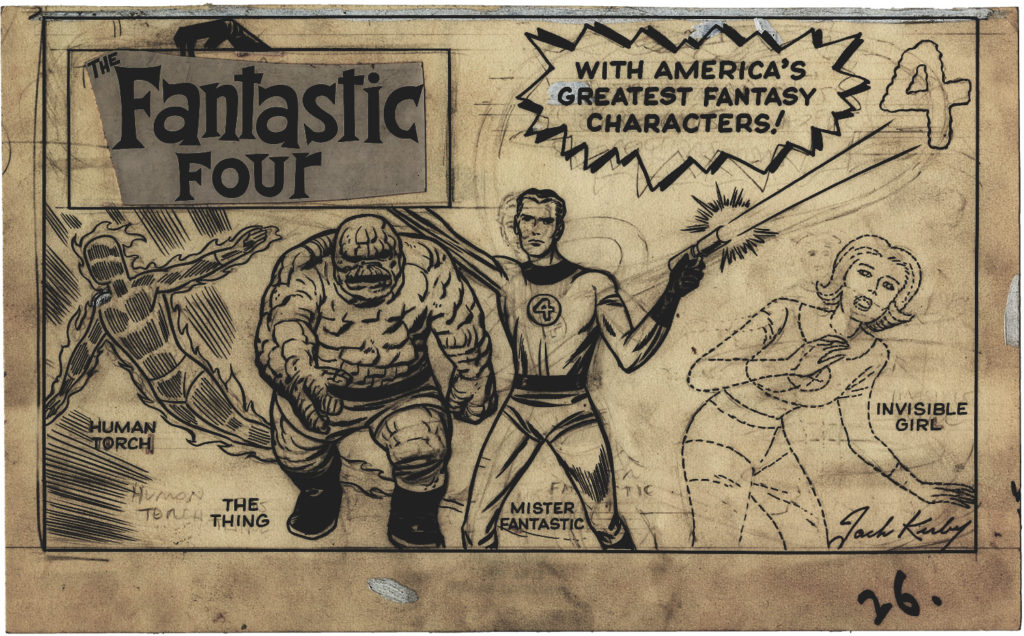

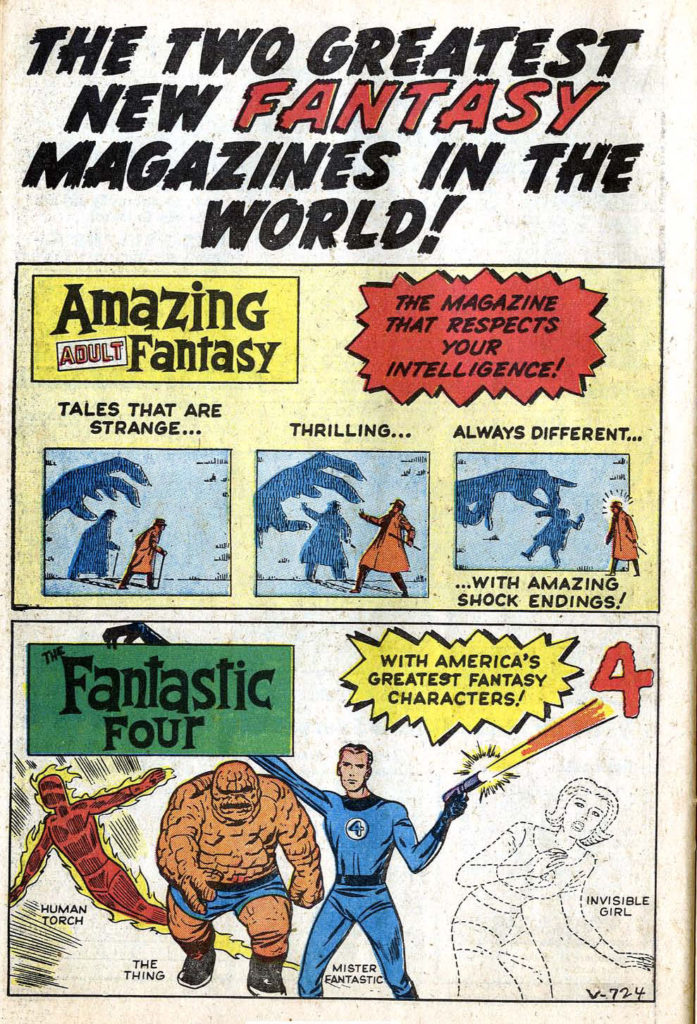

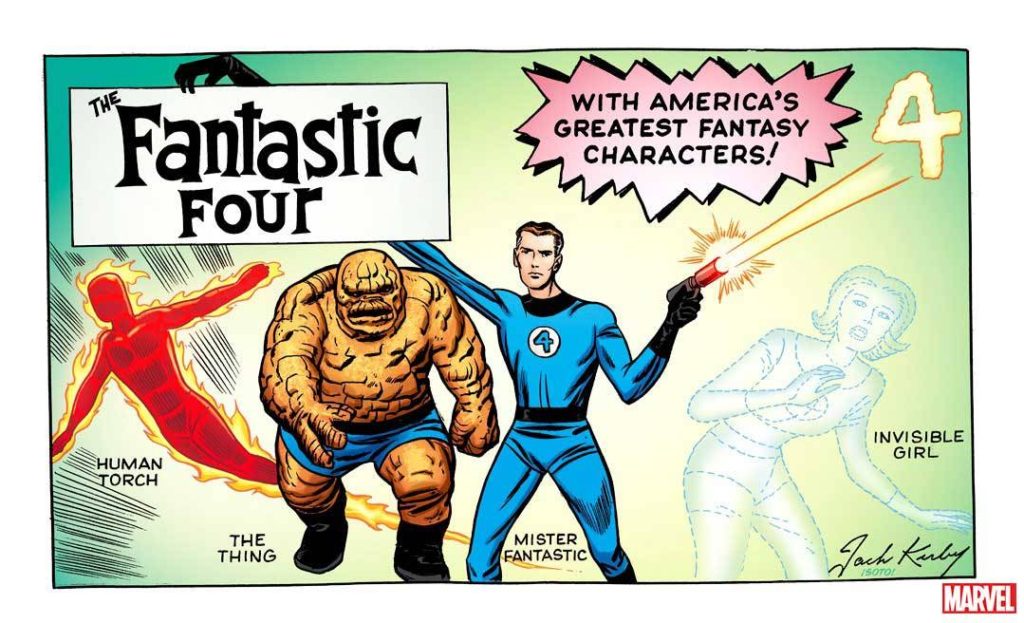

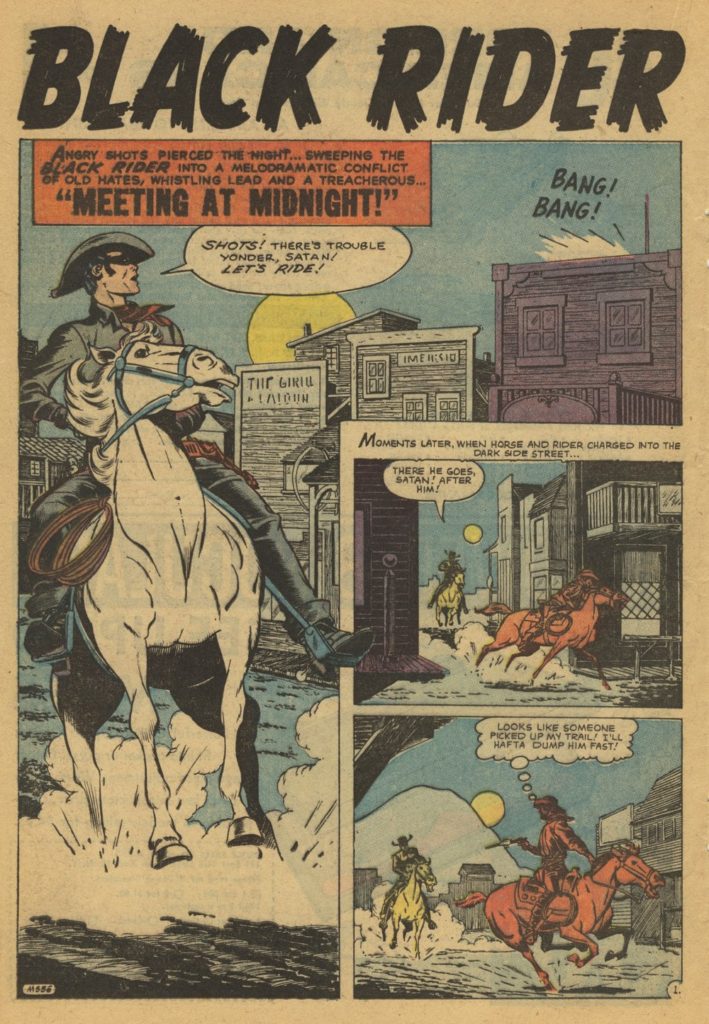

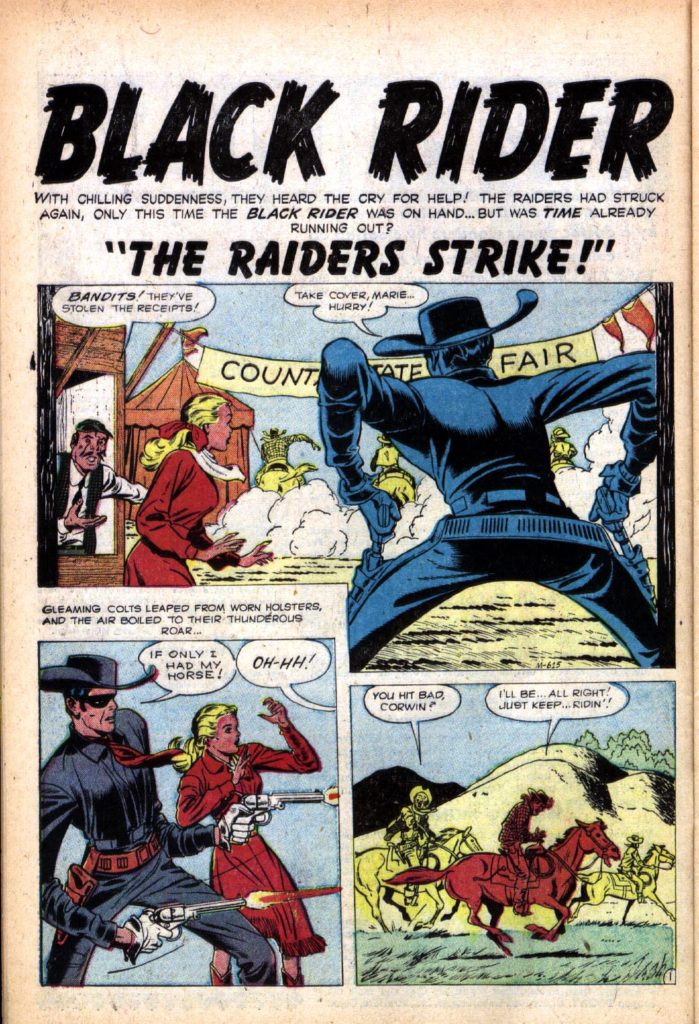

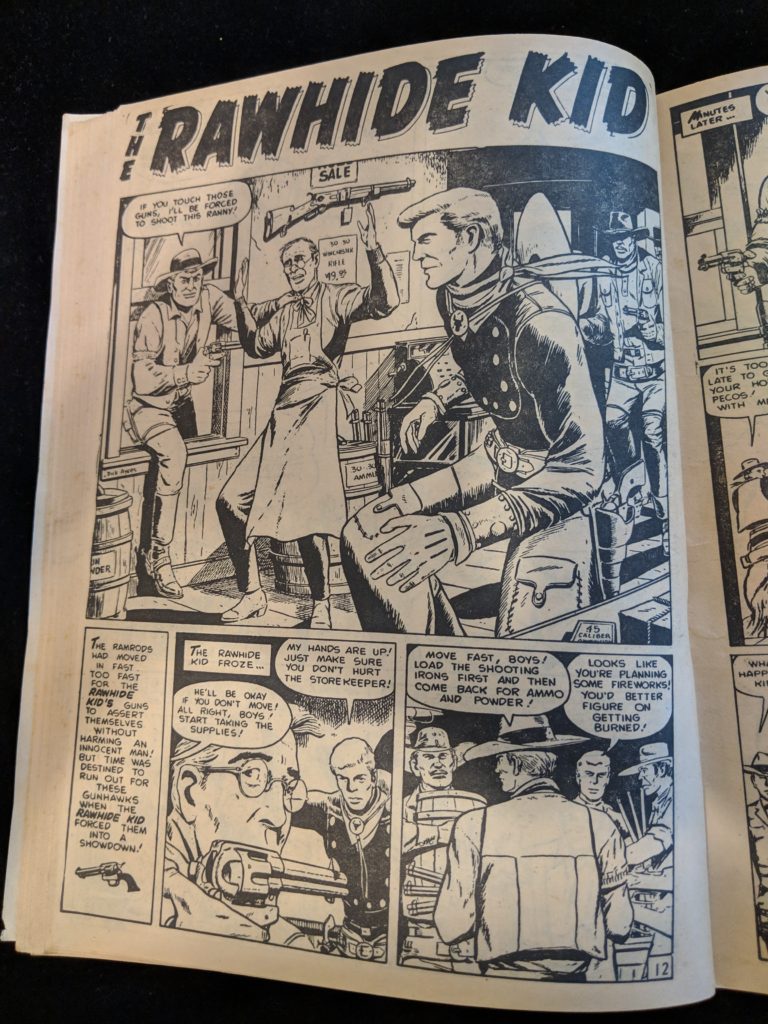

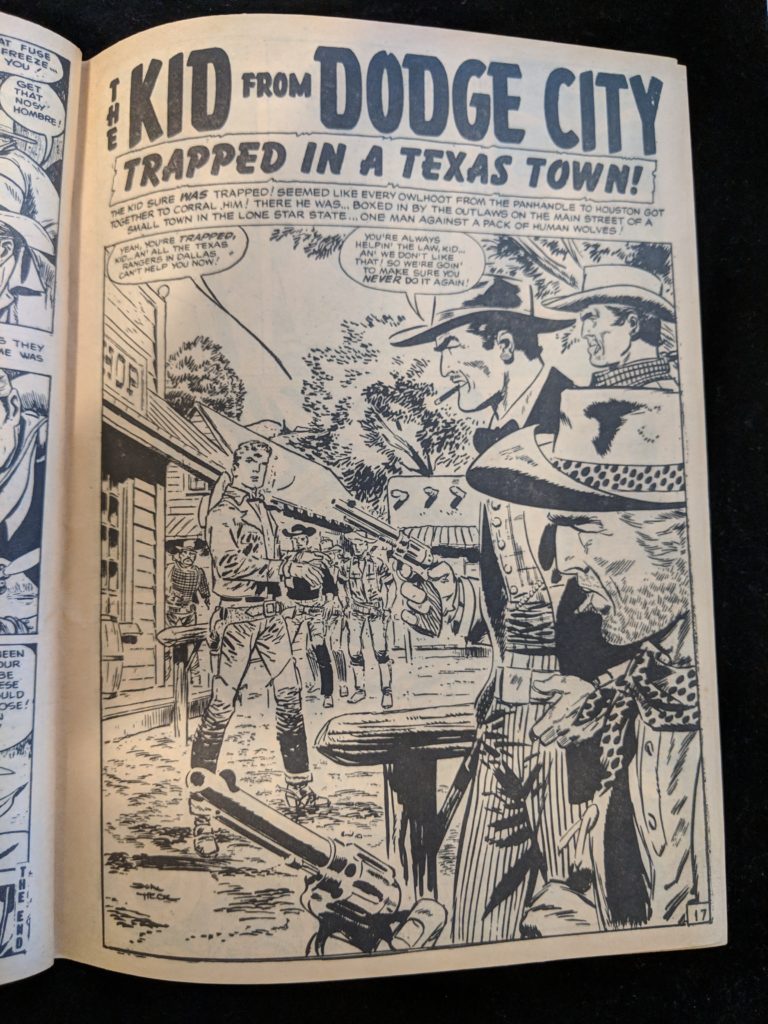

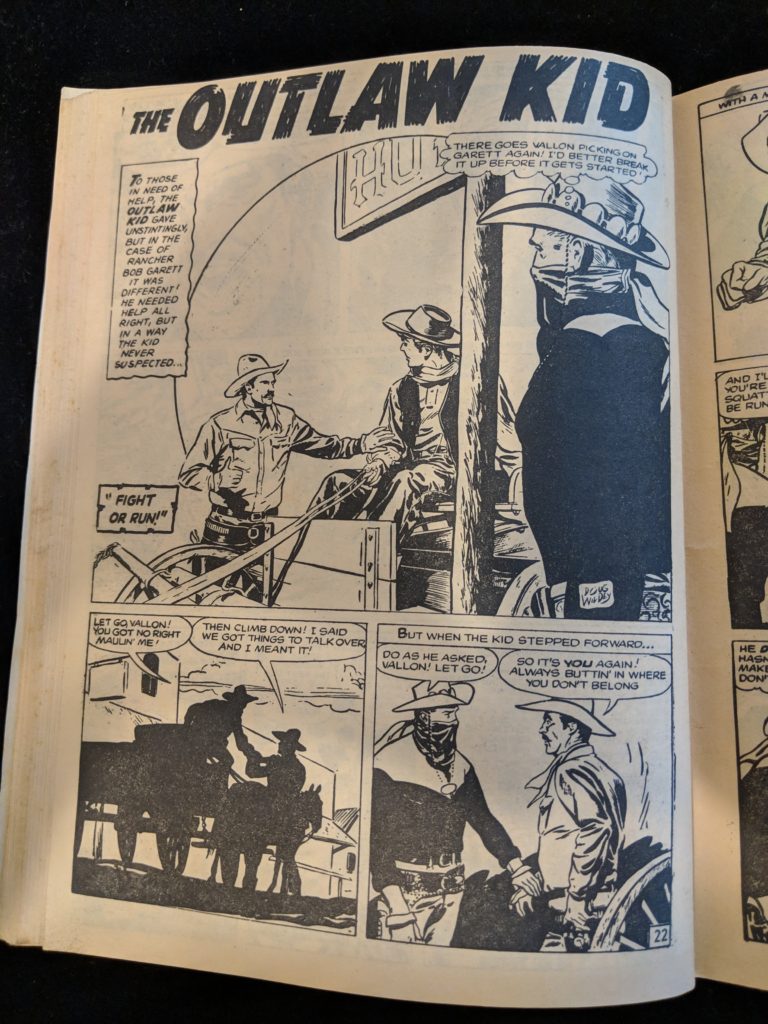

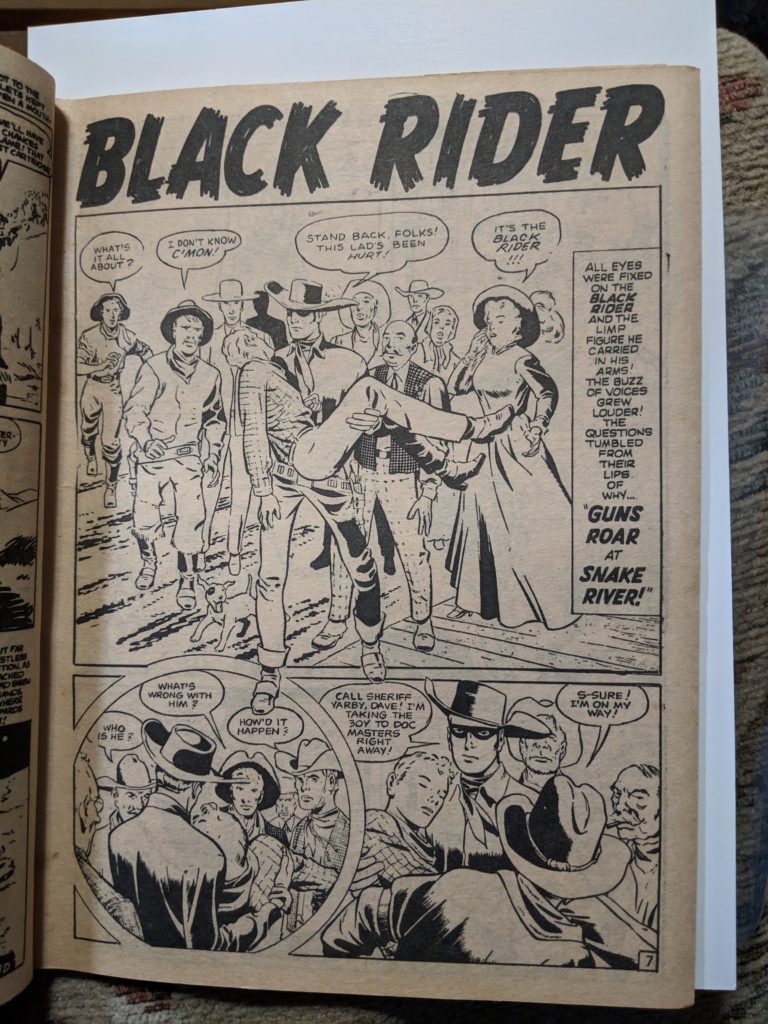

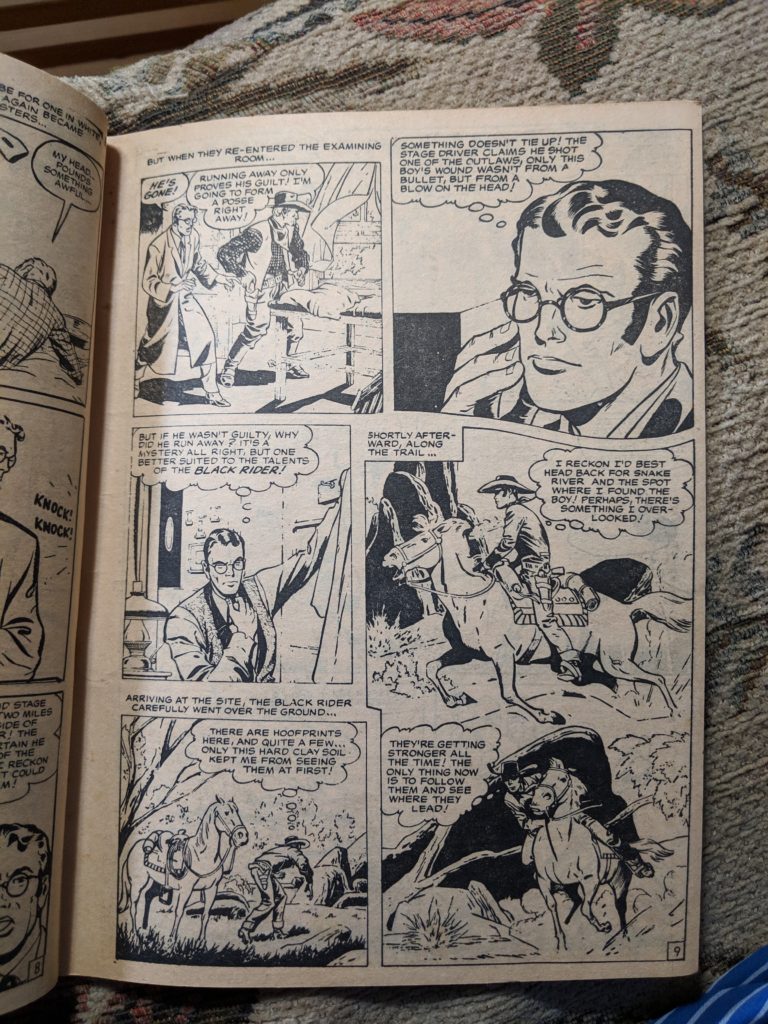

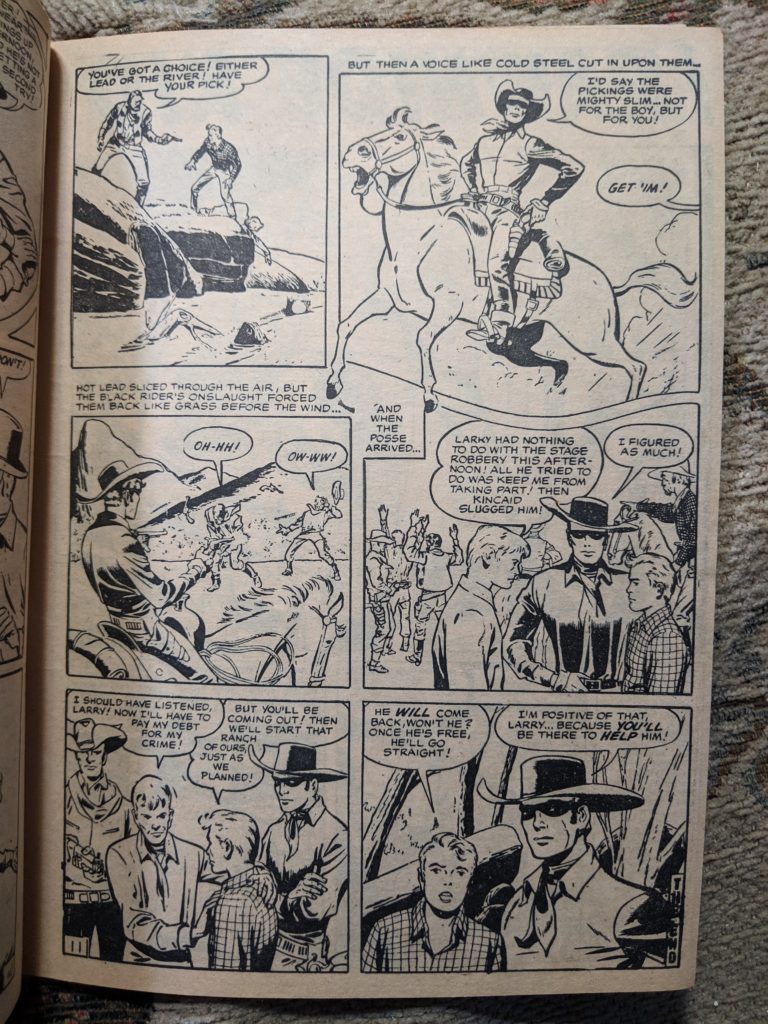

Above is what the art looks like. But using some photo editing adjustment tools, we can see some interesting items…

Above is what the art looks like. But using some photo editing adjustment tools, we can see some interesting items…